1. Introduction

Recent studies by Wang et al. [

1], Dulberg et al. [

2], and others argue that AI must evolve into a distributed ecosystem in which multiple AI entities interact, specialize, and collectively enhance intelligence. A central assertion is that a modular architecture can learn more efficiently and effectively to manage multiple homeostatic objectives, in nonstationary environments, and as the number of objectives increases.

Much of the origin of this approach lies in the early work of Wolpert and Macready [

3,

4] —more recently, Shalev-Schwartz and Ben-David [

5]—demonstrating that an optimizer tuned to be ‘best’ on one particular kind of problem must inevitably be ‘worst’ at some complementary problem set. Complex problems that divide ‘naturally’ into modular subcomponents can then be—it is hoped—efficiently addressed by an interacting system of cognitive modules, each individually tuned to be ‘best’ on the different problem components most representative of the embedding challenge environment. Success in such a ‘game’ requires matching cognitive system subcomponents to problem subcomponents in real time. This is not easy. As an anonymous commentator put the matter [

6],

Apparently a proved theorem cannot be entirely circumvented by a framework consistent in the same formal foundation system, so [Mixture of Experts] just redistributes the challenge across the framework’s underlying components.

In particular, the maintenance of dynamic homeostasis under the Clauswitzian ‘selection pressures’ of fog, friction, and adversarial intent is far from trivial, and, among humans, even after some considerable evolutionary pruning, high-level cognitive process remains liable to debilitating ‘culture-bound syndromes’ often associated with environmental stress and related, inherently toxic, exposures and subsequent developmental trajectories (e.g., [

7], Ch. 3).

We are, then, very broadly concerned with the maintenance of cognitive stability in a modular system under the burdens of what, in control theory, is called ‘topological information’ [

8] imposed by disruptive circumstances, internally or externally generated.

Maturana and Varela [

9] hold that the living state is cognitive at every scale and level of organization. Atlan and Cohen [

10] characterize cognition as the ability to choose an action—or a proper subset—from the full set of those available, in response to internal and/or environmental signals. Such a choice reduces uncertainty in a formal manner and implies the existence of an information source dual to the cognitive process studied. The argument is direct and places cognition under the constraints of the asymptotic limit theorems of information theory [

11,

12,

13].

More recently, the Data Rate Theorem [

8] establishes conditions under which an inherently unstable dynamical process can be stabilized by the imposition of control information at a rate exceeding the rate at which the process generates its own ‘topological information’. The model depicts a vehicle driven at high speed along a twisting, potholed roadway. The driver must impose steering, braking, and gear-shift information at a rate greater than the road imposes its own topology, given the chosen speed.

Most real-world cognitive phenomena, from the living state to such embodied machine cognition as High Frequency Stock Trading [

14,

15,

16], must act in concert with–be actively paired with–a regulator to successfully meet the demands of real-world, real-time function:

Blood pressure must respond to changing physiological needs while remaining within tolerable limits.

The immune system must engage in routine cellular maintenance and pathogen control without causing autoimmune disease by attacking healthy tissue.

The stream of consciousness in higher animals must be kept within ‘riverbanks’ useful to the animal and its social groupings, particularly among organized hominids, the most deadly predators on Earth for the best part of half a million years.

Human institutions and organizations, via ‘rule-of-law’ or ‘doctrine’ constraints, are notorious for cognition-regulation pairing.

Here, using the asymptotic limit theorems of information and control theories, we will explore, in a sense, the ‘metabolic’, ‘free energy’ and other such costs of this necessary pairing as the number of basic, interacting submodules rises, uncovering a truly remarkable set of scaling properties across the ‘fundamental underlying probability distributions’ likely to power and constrain a variety of important cognitive phenomena.

The probability models arising ‘naturally’ from this effort can serve as the basis of new statistical tools for the analysis of data related to the stability of cognitive phenomena across a broad range of phenomena. However, like the regression models derived from the Central Limit Theorem and related results, such tools do not, in themselves, ‘do the science’. This work has, consequently, focused on a range of models and modeling strategies. Not everything follows a pattern. Sometimes things go as or worse, hence our insistence on the analysis of dynamics across different underlying probability distributions.

Some current attempts at comprehensive cognitive models, e.g., ’integrated information theory’, ’the free energy principal’, ‘quantum consciousness’, have made claims of existential universality akin to a general relativity of biology and mind. This work, far more modestly, aims to derive tools that can aid the analysis of observational and experimental data, the only sources of new knowledge rather than new speculation.

That said, we do not at all denigrate the model-based speculations that might arise from our approach, provided they are ultimately constrained by effective feedback from data and experiment.

The development, unfortunately, is far from straightforward, and requires the introduction of some considerable methodological boilerplate, extending relatively simple ‘first order’ approaches abducted from statistical physics and the Onsager model of nonequilibrium thermodynamics, generalizing, in a sense, the results of Khaluf et al. [

17], Kringlebach et al. [

18], and other recent work.

An often-overlooked but essential matter is that information sources are not, like physical processes are assumed to be, microreversible, i.e., in English ‘the’ has a much higher probability than the sequence ‘eht’, implying a directed homotopy ultimately leading to groupoid symmetry-breaking cognitive phase transitions. Much–but not all–of this will be safely hidden in the relatively simple first-order formalism developed below.

Another common misunderstanding is the interpretation of Shannon uncertainty, as expressed mathematically, as an actual entropy. Following Feynman [

19] and Bennett [

20], information should be treated as a form of free energy that can be used to construct partition functions leading to higher-order free-energy constructs. This is, as Feynman remarks, a subtle matter.

More generally, as Khinchin [

12] indicates, for nonergodic stationary systems, each message stream converges to its own source uncertainty that cannot be expressed in ‘entropy’ format. A standard approach from statistical physics, however, still allows construction of a partition function in such cases, hence an iterated free energy, and, via a Legendre Transform, a compound entropy measure. The gradient of that compound entropy can be taken as a thermodynamic force, thereby defining the rate-of-change of the underlying variates, thereby permitting standard stochastic extensions of the models. Again, however, this provides only an entry-level, first-order attack on a barbed-wire thicket of cognitive phenomena and their inevitable pathologies.

Although modern medicine can often perform seeming miracles against an increasingly wide spectrum of infectious and chronic diseases, the culture-bound syndromes of ‘madness’ remain largely intractable.

The narrowly trained designers and builders of cutting-edge artificial intelligence systems and entities are entering a Brave New World.

3. A Single Cognition-Regulation Pairing

Here, we are interested in the dynamics of interaction between two entities—a ‘system-of-interest’ and its paired regulating apparatus—engaged separately in ‘real-world’ evaluations according to

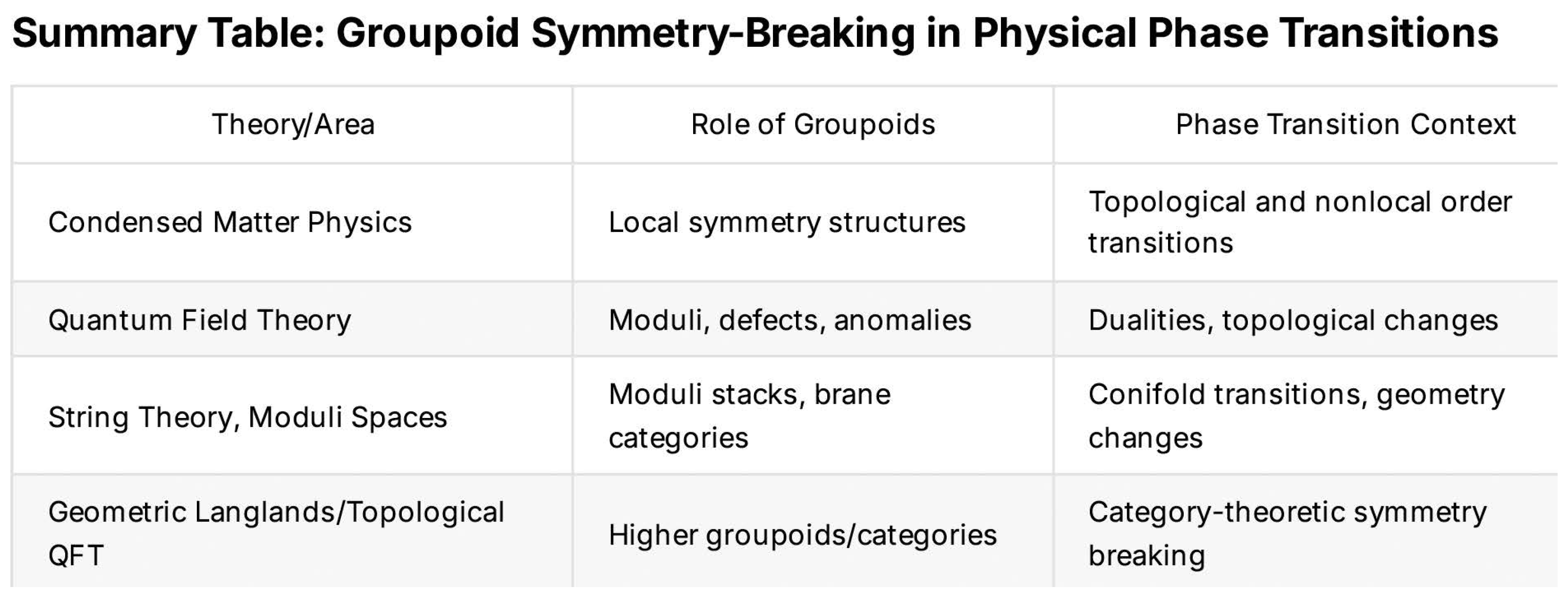

Figure 1, where each entity is concerned with its own channel capacity

—increasing

R to lower the distortion between what it intends and what it observes.

In rough consonance with the approaches of Ortega and Braun [

22] and Kringlebach et al. [

18], we consider a ‘simple’ probability distribution underlying overall system dynamics, say

, and construct an iterated probability for each component of the interaction individually, having the following form:

where

represents a

temperature analog that must be further characterized, and each

, again following Feynman’s ([

19], p. 146) adaptation of Bennett’s [

20] analysis, is itself to be interpreted as an initial free energy measure. Bennett argued that information itself has a kind of ‘fuel value’ or free energy content. Following Feynman, we take this and run with it. In what follows, ‘channel capacities’

will be used to build higher-order, iterated, free energy measures following from the statistical mechanical partition function.

That is, this formulation leads directly to a partition function definition of an

iterated free energy

F [

23,

24,

25]:

where

is some appropriate ‘average temperature’ that we take here as follows:

We next impose a first-order model,

, where the constant

g is an

affordance index that determines how well the resource rate

Z can actually be utilized, and, for convenience, take

as the Boltzmann Distribution, solving for

F as follows:

Dynamics are then defined in second order at the nonequilibrium steady state according to an Onsager nonequilibrium thermodynamics model [

26]:

where

S, as the Legendre Transform of

F [

24], is an entropy-analog, and we are able to omit the ‘diffusion coefficient’ in the second line of Equation (

6).

Solving the two relations

for the

leads to three solution sets for the nonequilibrium steady state (nss)—i.e., homeostatic/allostatic—conditions. The physically nontrivial one is the

equipartition1. Note that pathological values of and can force —the regulatory system supply demand—to grow so large that it becomes unsustainable. That is, homeostasis/allostasis of a cognitive/control dyad can be driven to failure by sufficient ‘environmental’ stress.

2. The ‘total energy rate’ Z can be lowered by raising the ‘affordance’ measures .

This relatively simple example provides a useful starting point for significant generalizations, at the expense of considerable, often nontrivial, conceptual and formal development.

4. Extending the Model I

As Stanley et al. [

27] describe, empirical evidence has been mounting that supports the intriguing possibility that a number of systems arising in disciplines as diverse as physics, biology, ecology, and economics may have certain quantitative features that are intriguingly similar. These properties are conventionally grouped under the headings of ‘scale invariance’ and ‘universality’ in the study of phase transitions.

Here, using the equipartition implied by Equation (

7), we impose a quasi-scale-invariant model and explore the resulting patterns of phase transition that affect and afflict homeostasis and allostasis under ‘stress’. The ‘quasi’ arises because one cannot simply abduct the dynamics of physical processes to the dynamics of cognition, particularly biocognition. At the very least, information sources ‘dual’ to cognitive phenomena [

13] are not micro-reversible, displaying, as mentioned above, directed homotopy.

An inverse argument generalizes the nss equipartition derived above across a full set of probability distributions likely to be characterized by biological, institutional, and machine cognition.

Fix the , and assume there are contending/cooperating agents, taking n as an integer. (In analogy with physical theory, we might actually need to take for some monotonic increasing function of n.)

We are, again, envisioning at least an individual enmeshed in a social environment. Then, on this basis, calculate the most general possible form of the corresponding average R.

The relations of interest for possible underlying probability distributions are then taken according to the

first-order quasi-scale invariant expressions:

where, again,

n is an integer, and the appropriate functional form of

must now be found.

See Khaluf et al. [

17] for a discussion of ‘ordinary’ scale invariance, where

for some monotonic increasing function

.

In general, it may be necessary to replace n with some appropriate monotonic increasing function , but for algebraic simplicity, we will continue with the simple, first-order model.

Equation (

6) is reexpressed in terms of the

, imposing the nonequilibrium steady state condition:

for all possible

, so that the

are indeed fixed at the same value across all possible probability distributions.

What functional forms of R make this true?

The argument is not quite trivial but straightforward.

Requiring in Equation (

6), generalizes to a full class of ‘averaging’ functions

, given proper dimensional extension of

S.

For

n dimensions, a direct solution by induction is as follows:

which applies to both arithmetic and geometric averages. This is a simplification from a more elaborate treatment that would add considerable mathematical overhead to an already burdened development.

We will reconsider this problem, and that of Equation (

4), from a different and perhaps deeper perspective below.

Here, we carry the argument further, treating Equation (

8) as an explicit function of

X a nonequilibrium steady state, and extending the Onsager analysis:

where in the third line we again invoke the Legendre Transform to define an ‘entropy’ in terms of a ‘free energy’.

Again, it may be necessary to replace the integer

n in the first line of Equation (

11) by an appropriate monotonic increasing function

. In physical systems, typically

.

Higher order ‘Onsager-like’ [

26] expressions for the entropy-analog may well be needed, for example,

for appropriate

. Such expressions may be system-specific, again leading to the second relation in Equation (

11), but producing more involved expressions for

.

Below, we extend the argument to cases where as t increases, introducing ‘frictional’ delays.

Here, the essential point is that calculating allows finding critical values under different probability distributions and ‘Onsager-type’–or other–models. Again, scaling with n may not be the simple linear model used here.

Thus, a direct, comprehensive, approach to system stability, via this approach, is to ‘simply’ demand that be real-valued, given that is a probability distribution on .

For, in order, Boltzmann, k-order Lomax, and Cauchy Distributions—instantiating the non-zero requirement—and sequentially, the Rayleigh, k-order Erlang, and k-order chi-square distributions,

where all scale parameters have been set equal to one and, in general, one might expect

for some appropriate increasing function. Again, detailed development would add more mathematical overhead to an already overburdened argument.

Note the following:

The second condition is most easily proved by direct substitution.

is the Lambert W-function of order m that satisfies the following relation:

W is real-valued only for and .

Equation (

13) is strictly equivalent to the condition that there is no solution to

if

. If the distribution is nonmonotonic and a solution exists, there will be more than one solution form. The first three relations of Equation (

13) are associated with monotonic distributions having mode zero.

We are concerned with the

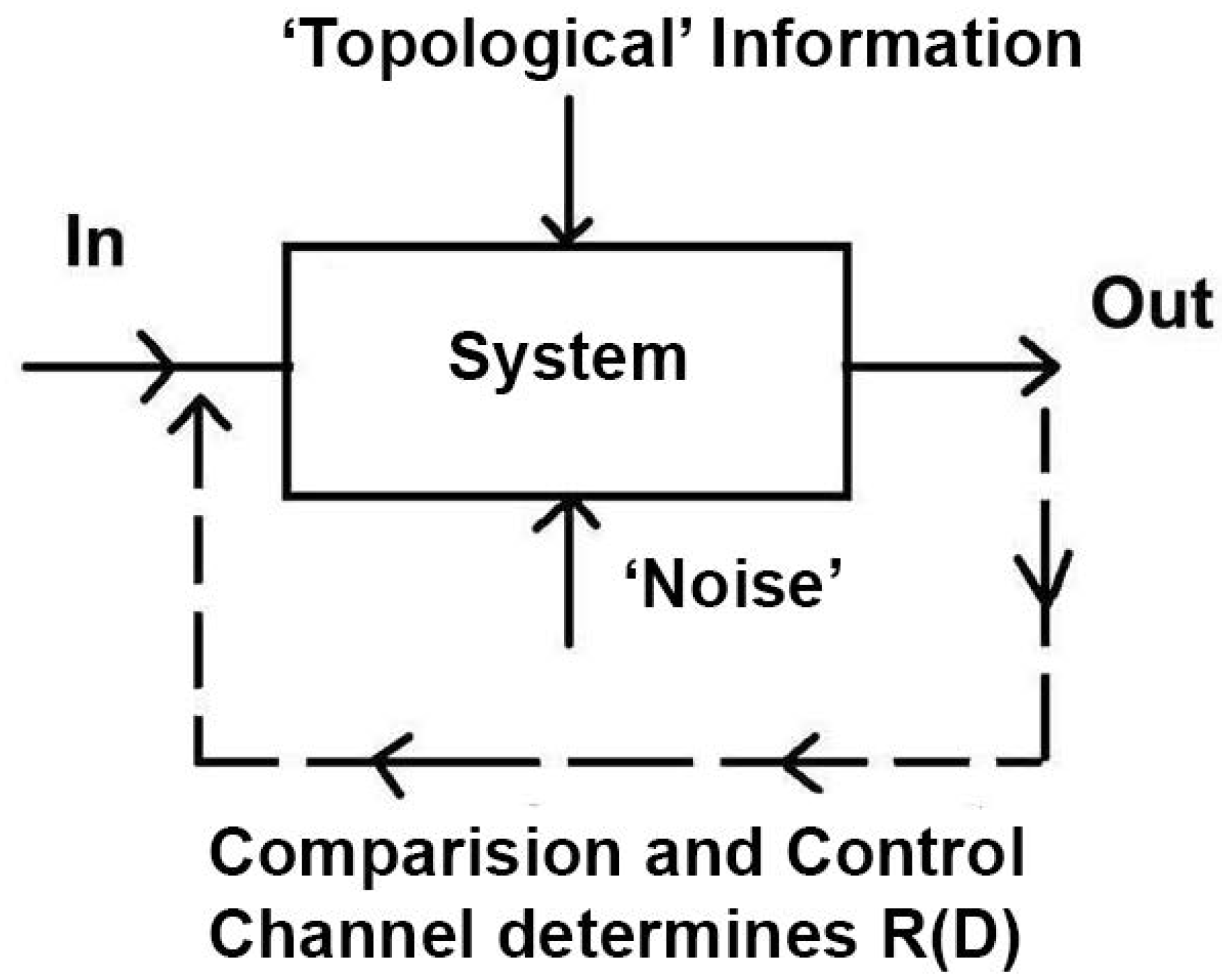

rising branches representing cooperation between system subcomponents, displaying in

Figure 2, patterns of limiting behavior with increasing

n for, respectively, the Rayleigh, second-order Erlang, and fourth-order Chi Square Distributions. These are nonmonotonic. The regimes above the top branch of the ‘C’ are stable for cooperating systems.

The essential point for this analysis is that, like for the Boltzmann Distribution, the ‘cost’ in X for cooperating modes does not increase linearly with rising n. For the Boltzmann Distribution model, doubling n, i.e., pairing each cognitive submodule with a regulator, increases the rate of ‘resource’ demand as .

For cooperating cognition/regulation dyads, the ‘cost’ in units of X does not increase in proportion to the shift . From the perspective of evolution under selection pressure, this seems a small price to pay for a grand increase in stability of function.

Again, here, the branches can be taken as indexing cooperative coalitions, while the branches represent contending system dynamics under rising n, which is another matter.

After some algebra, results similar to

Figure 2 are found for the Levy and Weibull distributions, although the Levy is difficult to parse.

We can now extend the ‘energy’ argument of Equation (

7), recalling that, for all

j,

, the equipartition value. Applying the arguments above, we set

from Equation (

13) for the appropriate underlying probability distribution.

For convenience, we assume a set of

n identical systems, with fixed forms for the

and fixed values of the

under some particular probability distribution. Then

Recall that, if g is monotonic increasing, so is .

For example, assuming a Boltzmann Distribution,

which does not increase linearly with

n by virtue of the division by

in

.

Adopting the simple linear model

,

which makes intuitive sense.

Further, the first relation of Equation (

17) can be solved for

n (or

), generating necessary conditions for

.

For example, under the Boltzmann Distribution,

for

in the Lambert W-function, imposing the necessary condition:

From Equations (15)–(17), this is a general result for the linear model: That is, the same expression—with different right-hand terms—is ‘easily’ found for the other probability distributions leading to Equation (

13).

6. Groupoid Symmetry-Breaking Phase Transitions

There is yet more to be teased out from behind the veils of Clausewitzian Fog-and-Friction. So far, we have treated ‘underlying probability distributions’ as the central, fixed star in a kind of planetary dynamic, leading to the methodological harvests of Equation (

13) and what follows from the network relation

(recalling that, in general,

).

What happens when is itself perturbed by fog and friction?

Most simply, this can be found by calculating the nonequilibrium steady state:

based on the generalized ‘frictional’ stochastic differential equation

using the Ito Chain Rule.

The relation defining the NSS is ‘easily’ found as follows:

where the second form follows from the second expression in Equation (

20), i.e.,

.

Equation (

29) generates solution set equivalence classes

that can be seen as arising from the functions

or

.

1. For reasons that will become more salient, if not intrusive, we are principally concerned with these equivalence classes rather than with the functions themselves.

2. The term

may be interpreted as the scale of change or ‘characteristic length’ relating how sharply the density changes versus its curvature at a point. It is analogous to, but different from, the classic ‘hazard rate’ at which signals are detected. For the Exponential Distribution

, the hazard rate is

m and the characteristic length

.

3. For convenience, we adopt ‘simple volatility’, i.e.,

, with

as the exponential and Arrhenius models from above for, respectively, the Boltzmann and Second Order Erlang Distributions, and plot

to generate

Figure 6.

Again, the second-order Erlang represents the convolution of two identical exponential distributions, akin to replacing ‘mission command’ initiative with a two-stage ‘detailed command’ protocol in military or business enterprise [

30].

The distributions are, respectively, monotonic and nonmonotonic. The results, in

Figure 6, are

a Boltzmann-exponential,

b Boltzmann–Arrhenius,

c Erlang-exponential, and

d Erlang–Arrhenius. Again,

Here, in both expressions for .

These distinct solution sets, representing markedly different fundamental interactions between internal probabilities, ‘friction’ from and , and ‘fog’ from , can be grouped together as equivalence classes even as the internal parameters defining and are varied.

As the Mathematical

Appendix A explores in some detail, equivalence classes lead to an important generalization of elementary ideas of group symmetry, i.e., groupoids, for which products are not defined between all possible element pairings [

31].

The simplest groupoid is the disjoint union of groups. Imagine two bags containing the same number of identical ball bearings, each of which can be characterized by the three-dimensional rotation group. Remove a ball bearing from one bag, make a deep indentation in it with a hard-metal punch, and return it to the original bag. The disjoint union of three-dimensional rotation groups in one of the bags has now been broken. One bearing is now symmetric only via rotation about an axis defined by the indentation.

The physical act of striking a ball bearing with a hard-metal punch has triggered a groupoid symmetry-breaking phase transition, analogous to, but distinct from, group symmetry-breaking phase transitions such as melting a snow crystal, evaporating a liquid, or burning a diamond.

Each panel of

Figure 6 defines a particular set of equivalence classes that, via the somewhat mind-bending arguments of the

Appendix A, defines a groupoid. Changes within fog/friction/probability patterns under the perturbations of external circumstances—like the hard-metal punch on the ball bearing—trigger punctuated groupoid symmetry-breaking phase transitions in the kind of systems we have studied. That is, sufficiently challenged cognitive structures will experience sudden shifts among the panels of a vastly enlarged version of

Figure 6.

A more extensive discussion of groupoid symmetry-breaking phase transitions by the Perplexity AI system is found in the

Appendix A.

Cognition, even with regulation, is a castle made of sand.

7. Iterated System Temperature

Subsystems of living organisms consume metabolic free energy (MFE) at markedly different rates. For example, among humans, Heart/Kidneys, Brain, and Liver typically require, respectively, 440, 240, and 200 KCal/Kg/day of MFE, while resting Skeletal Muscles and Adipose Tissue require only 13 and 4.5 Kcal/Kg/day ([

32], Table 4).

These marked differences, however, are encapsulated within a ‘normal body temperature’ of ≈98.6 deg.F.

This is not as simple as it seems, nor as treated in the first iteration of Equations (4) and (10) above.

Here, we have, via an ‘equipartition’ argument, condensed closely interacting nonequilibrium steady state subcomponents of a larger enterprise in terms of the quantity X from Equations (20)–(29). Taking the perspective of the previous section, more can be done, in particular, leading to the definition of an ‘iterated temperature’ construct that seems akin to the normal body temperature.

The essential assumption is, again, that, under the stochastic burden of Equation (

28), the basic underlying probability distribution is preserved in a nonequilibrium steady state

, leading to the second form of Equation (

29). Then the ‘free energy’ construct

is expressed as follows:

Recall now, from above, the embodied Rate Distortion Control Theory partition function argument defining ‘free energy’

F in terms of a temperature analog

g:

where,

g, has become an iterated function of

X, the equipartition energy measure. From here on, we will write this as

to differentiate it from the ‘simple’ temperature analog of previous studies.

That is, here, we are interested in the solution to the following relation:

given the NSS condition , i.e., the quasi-preservation of the underlying basic probability distribution of the overall system.

We are, in a sense, reprising the calculations of Equations (4) and (10) from a different perspective.

More specifically, we contrast a simple one-stage ‘mission command’ system based on a Boltzmann Distribution with a two-stage ‘detailed command’ process that passes decisions across two sequential Boltzmann stages, giving a process described overall by a second-order Erlang Distribution. Under the impact of ‘noise’ defined by Equation (

28), each ‘cultural’ form attempts homeostasis, the preservation of its inherent nature, i.e.,

.

Thus, we, respectively, set

and assume ordinary volatility

. Then, again via the Ito Chain Rule calculation [

29],

where

is the Lambert W-function of orders

. The

expressions are then the iterated temperatures of the entire system under the reduced equipartition defining

X across subsystems.

Here, we adopt the negative- form of the W-function in , as the positive form generates only negative temperatures that, in physical systems, are associated with grossly unstable ‘excited states’.

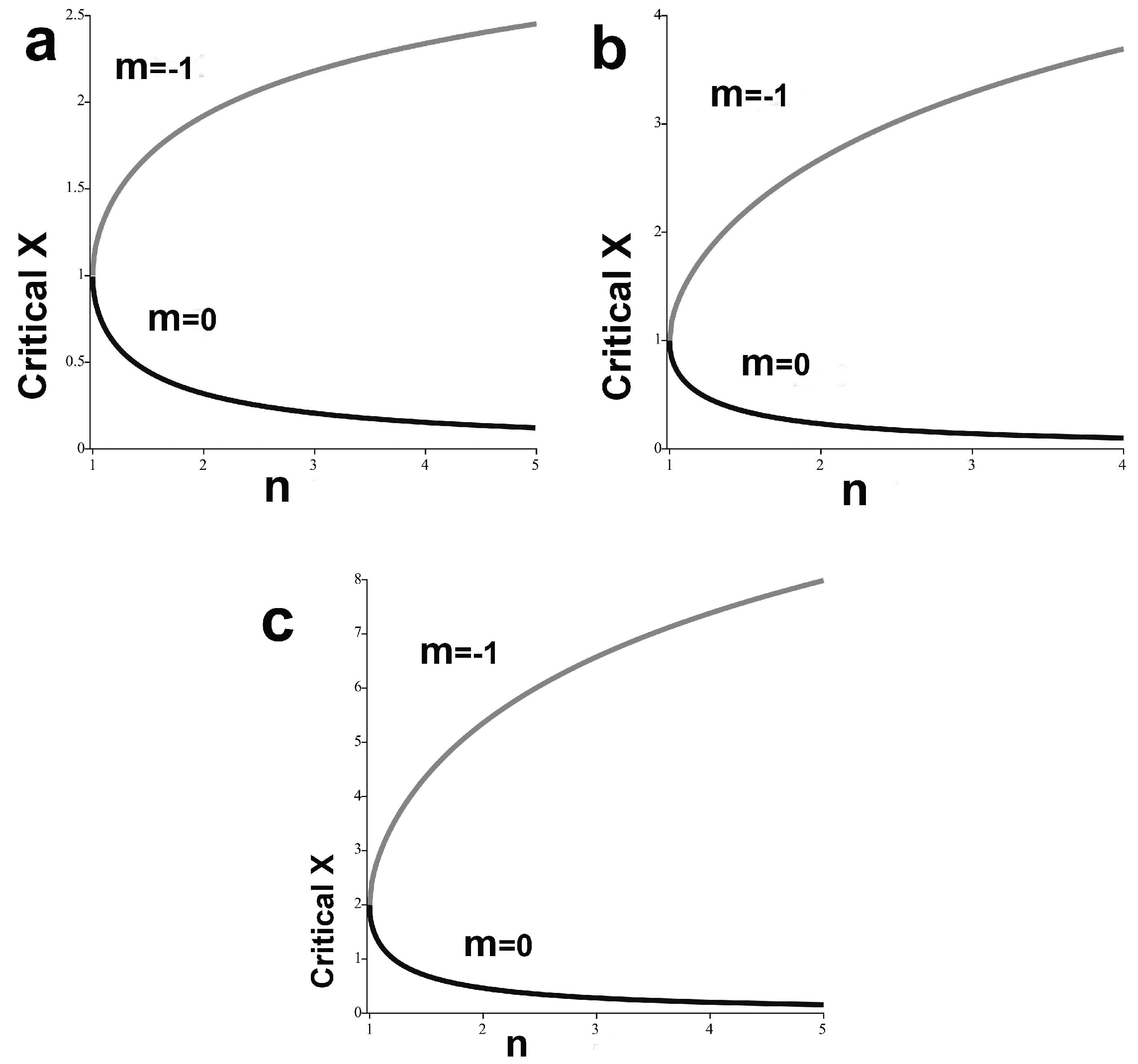

Figure 7a,b show the two forms of

, setting

, with

as indicated.

Sufficient ‘noise’ drives both systems into zones of instability where the relation fails. This occurs, via the properties of the W-function, for, respectively, and or . The contrast between stable zones is noteworthy: the Detailed Command model is at best only slightly stable compared with our version of Mission Command.

Again, each mode of the underlying ‘culture’, when stressed, attempts to maintain homeostasis as the nonequilibrium steady state .

It is ‘not difficult’ to extend these results across orders of iteration of the underlying Boltzmann Distribution via a

k-stage ‘cancer initiation’ model based on the Gamma Distribution:

where

is the Gamma Function that generalizes the factorial function for integers.

Then the nss condition

, under the Ito Chain Rule, gives the following:

The first relation can easily be solved as in an expression too long to be written on this page.

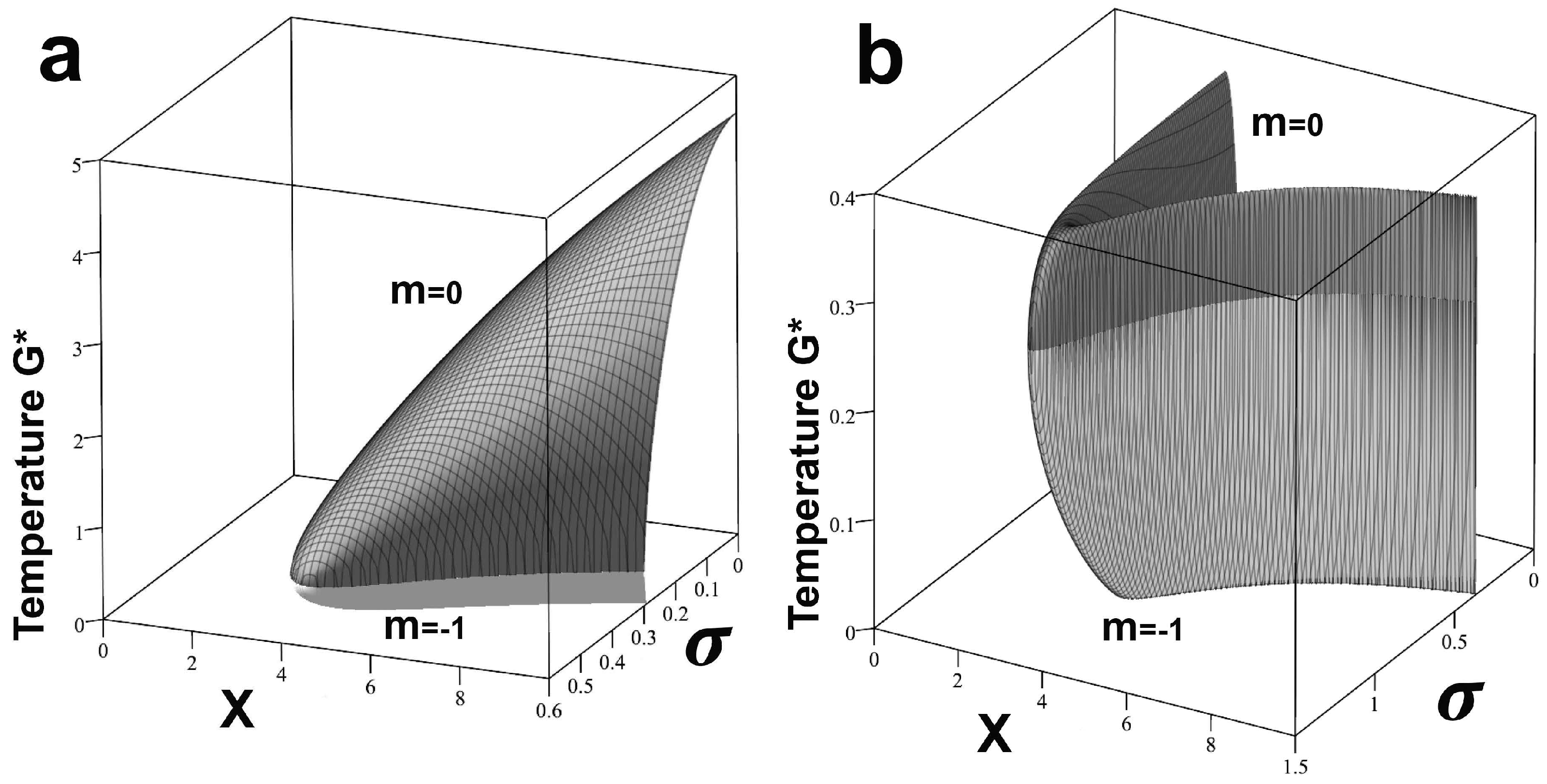

We can conceptually simplify matters slightly by generating a three-dimensional ‘criticality surface’

across the decision level index k by (1), using the necessary condition for real-valued Lambert W-functions of orders

, and (2), setting

, while varying the boundary conditions

. This is done via the second expression of Equation (

36):

The result is shown in

Figure 8a,b for two boundary condition pairs:

and

.

One possible inference from this development is that the approach we have taken permits the development of a very rich body of statistical tools for data analysis. Like all such matters, however, error estimates and basic validity entail a correspondingly rich range of possible devils-in-the-details.

In the Mathematical Appendix, we explore a ‘higher iteration’ in the detailed command structure, i.e., doubling the two-level dynamic based on the second-order Erlang Distribution. The figure shows an initial two-stage ‘tactical’ decision level, followed by a second two-stage ‘operational’ or ‘strategic’ command level. The results are not reassuring.

It is important to note that other selection pressures may operate. That is, Equation (

31) assumes the most essential matter is the preservation of the underlying probability distribution through the nonequilibrium steady state

. What if environmental selection pressure enforces the preservation of some other quantity, for example, a ‘Weber-Fechner’ sensory signal detection mode

instead of

? Then

, under the Ito Chain Rule, leads to the following:

Taking

again produces something much like

Figure 7.

We can take this one step further by defining a ‘collective cognition rate’ based on the underlying probability distribution of the overall multi-modular system, given the Rate Distortion Control Theory model in

Figure 1. The essential point is to define ‘system temperature’ as

from Equations (34) or (38). Then, given the distribution form

, and a basic Data Rate Theorem stability limit

, the cognition rate, in analogy with a chemical physics reaction rate approach (e.g., Laidler [

33]) becomes the following:

For the particular Boltzmann and second-order Erlang Distributions studied here,

Figure 7 and friends are transformed as follows:

Details are left as an exercise. The general forms of

are, however, similar to

Figure 7.

Note that the ‘Boltzmann’ part of Equation (

40) produces the classic inverted-U ‘Yerkes-Dodson Effect’ pattern of cognition rate vs. ‘arousal’

X across a variety of plausible

nonequilibrium steady state restrictions [

30,

34].

8. Discussion

There seem to be ‘universality classes’ for cognitive systems, determined by the nature of the underlying probability distributions, e.g., monotonic or nonmonotonic, and by the nature of their embedding environments. Other examples may become manifest across different cognitive phenomena, scales, and/or levels of organization.

In particular, the transcendental Lambert W-function is used to solve equations in which the unknown quantity occurs both in the base and in the exponent, or both inside and outside of a logarithm [

35]. Similarly, problems from thermodynamic equilibrium theory with fixed heat capacities parallel the results shown in

Figure 2.

Indeed, Wang and Moniz [

36] make explicit use of the Lambert W-function in the study of classical physical system phase transitions, using arguments that are recognizably similar to those developed here for cognitive phase transitions. Likewise, Roberts and Vallur [

37] use the W-function in their study of the zeros of the QCD partition function, another phase transition analysis.

The Perplexity AI system [

38] contrasts physical and cognitive phase transition models in these terms:

![Stats 08 00117 i001 Stats 08 00117 i001]()

Both physical and ‘cognitive’ theories are based on probability distribution arguments ‘in which the unknown quantity occurs both in the base and in the exponent, or both inside and outside of a logarithm’. Cognitive phenomena, of course, act over much richer and more dynamic probability landscapes. Cognitive system probability models will, consequently, require sophisticated and difficult conversions into statistical tools useful for the analysis of observational and experimental data.

Khinchin [

39] explored in great detail the rigorous mathematical foundations of statistical mechanics, based on such asymptotic limit theorems of probability theory as the Central Limit and Ergodic Theorems. Here, we outline the need for the parallel, yet strikingly different, development of a rigorous ‘statistical mechanics of cognition’ based on the asymptotic limit theorems of information and control theories. Such developments must, however, inherently reflect the directed homotopy and groupoid symmetry-breaking mechanisms inherent to cognitive phenomena.

There are important matters buried in this formalism:

We study systems at various scales and levels of organization that are, by

Figure 1, fully

embodied in the sense of Dreyfus [

14], so that their cognitive dynamics may be, or become, ‘intelligent’ in his sense.

is basically a ‘rate’ variate, and the existence of a minimum stable for cooperating cognitive/regulation dyads is consistent with John Boyd’s OODA Loop analysis in which a central aim is to force the rate of confrontation to exceed the operating limit of one’s opponent, breaking homeostatic or allostatic ‘stalemate’. Predator/prey cycles of post and riposte come to mind.

The cost of pairing cognitive with regulatory submodules, which is necessary for even basic stability in dynamic environments, scales sublinearly with the inherent doubling of modular numbers across a considerable range of basic underlying probability distributions likely to characterize embodied cognition. This appears to be a general matter with important evolutionary implications across biological, social, institutional, and machine domains.

Nonetheless, in spite of ‘best case’ assumptions and deductions, failure of nominally ‘effective’ cognition on dynamic environments is not a ‘bug’, but is an inevitable feature of the cognitive process of any and all configurations, at any and all scales and levels of organization, including systems supposedly stabilized by close coupling between cognitive and regulatory submodules. See the Appendix for a surprisingly broad literature review by the Perplexity AI system.

The last point has particularly significant implications. A recent study of nuclear warfare command, control, and communications (NC3) by Saltini et al. [

40] makes the assertion

Because… [strategic warning, decision support and adaptive targeting]… are independent and tightly coupled, the potential role of AI is not limited to a single application; instead, it can simultaneously enhance multiple aspects of the NC3 architecture.

The introduction of AI entities—even when tightly coupled with draconian regulatory modules—cannot be assumed to significantly stabilize or enhance NC3 or any other critical system. Placing NC3 architectures under AI control merely shifts, obscures, and obfuscates failure modes.

This being said, as a reviewer has noted, the approach advocated here has a number of limitations:

The g and families used here are simplifications. Real systems may deviate. Sensitivity analysis— and SDE’s—helps but does not establish universality.

Validation has been minimal by design. Thresholds/phase transitions should be viewed as testable predictions, not established empirical facts.

Results may not hold in adversarial, highly non-stationary, or strongly path-dependent settings without additional assumptions or new proofs.

Again, this being said, on the basis of our—and much similar—work, the Precautionary Principle should constrain the use of AI in such safety-critical domains as NC3.

Further work will be needed to fully characterize the effects of Clausewitzian fog and friction across the full set of probability distributions likely to underlie a wide spectrum of observed cognitive phenomena, but what emerges from this analysis is the ubiquity of failure-under-stress even for ‘intelligent’ embodied cognition, even when cognitive and regulatory modules are closely paired.

There is still No Free Lunch, much in the classic sense of Wolpert and MacReady [

3,

4].