Mapping Research on the Birnbaum–Saunders Statistical Distribution: Patterns, Trends, and Scientometric Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1

- Theory and methods—What theoretical advances, estimation techniques, and model extensions have been developed for the BS family?

- RQ2

- Applications and impact—In which scientific domains has the BS distribution been most influential, and how has its use evolved across disciplines?

- RQ3

- Research structure—What collaboration networks, thematic clusters, and knowledge gaps characterize BS-related literature?

- RQ4

- Future directions—What emerging trends and methodological priorities are suggested by bibliometric evidence and text analytics?

- (i)

- To map the methodological and applied evolution of the BS distribution using curated bibliometric data and targeted literature synthesis.

- (ii)

- To identify dominant themes, research communities, and structural gaps through network visualization and thematic analysis.

- (iii)

- To highlight emerging trajectories and future research opportunities informed by quantitative evidence from text mining and citation dynamics.

2. Theoretical and Methodological Foundations

2.1. The Birnbaum–Saunders Distribution

2.2. The Log-Birnbaum–Saunders Distribution

2.3. Computational Implementation of the BS Distribution

3. Bibliometric Methodology

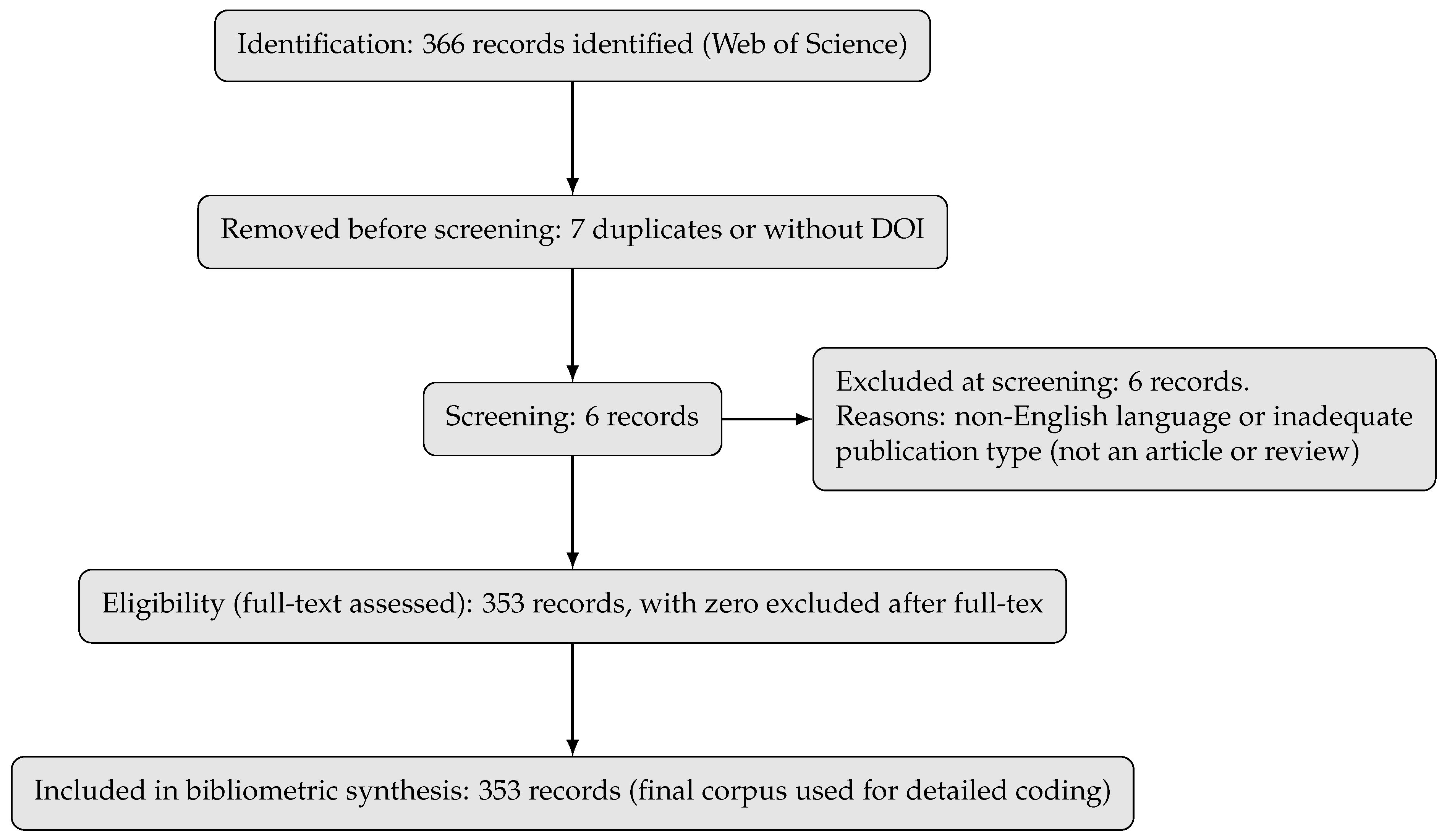

3.1. Search and Screening (PRISMA Method)

- Inclusion of peer-reviewed items (journal articles and peer-reviewed conference proceedings).

- Exclusion of records lacking core metadata (title, abstract, or DOI), consistent with the pre-specified English-language scope.

- Removal of any residual duplicates after DOI harmonization across databases.

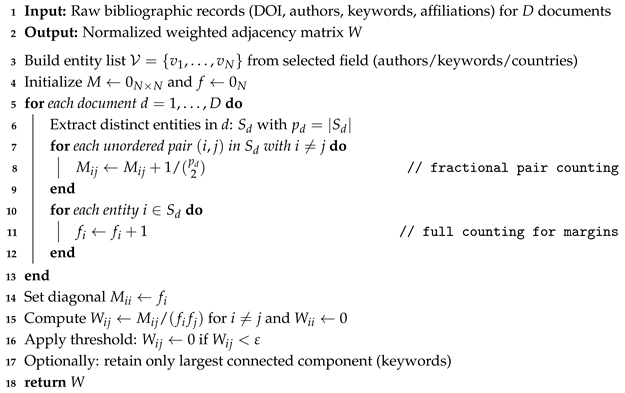

3.2. Construction and Normalization of Co-Occurrence Matrices

- Fractional pair counting—If document d contains distinct entities, each unordered pair , , receives

- Full counting for margins—The diagonal stores the document frequency so .

3.3. Network Layout and Community Detection

- Betweenness on the unweighted simple graph (shortest-path counts).

- Closeness using weighted shortest-path distances (reported for nodes in the largest component).

- Pagerank on the row-normalized weighted adjacency with damping factor [76].

3.4. Thematic Mapping (Callon Centrality–Density)

3.5. Matrix Construction, Normalization, Graphs, and Clustering

| Algorithm 1: Construction and normalization of the co-occurrence matrix |

|

| Algorithm 2: Layout and community detection |

1 Input: Weighted adjacency W, seed for layouts 2 Output: Coordinates , community labels 3 Rescale weights 4 Compute preferred distances for 5 Initialize coordinates (such as random or spectral) 6 Minimize energy (2) via iterative optimizer (Newton–Raphson or quasi-Newton) until convergence 7 Run Louvain algorithm on W to obtain communities 8 Compute centralities (betweenness, closeness, PageRank) 9 return coordinates, community labels, centralities |

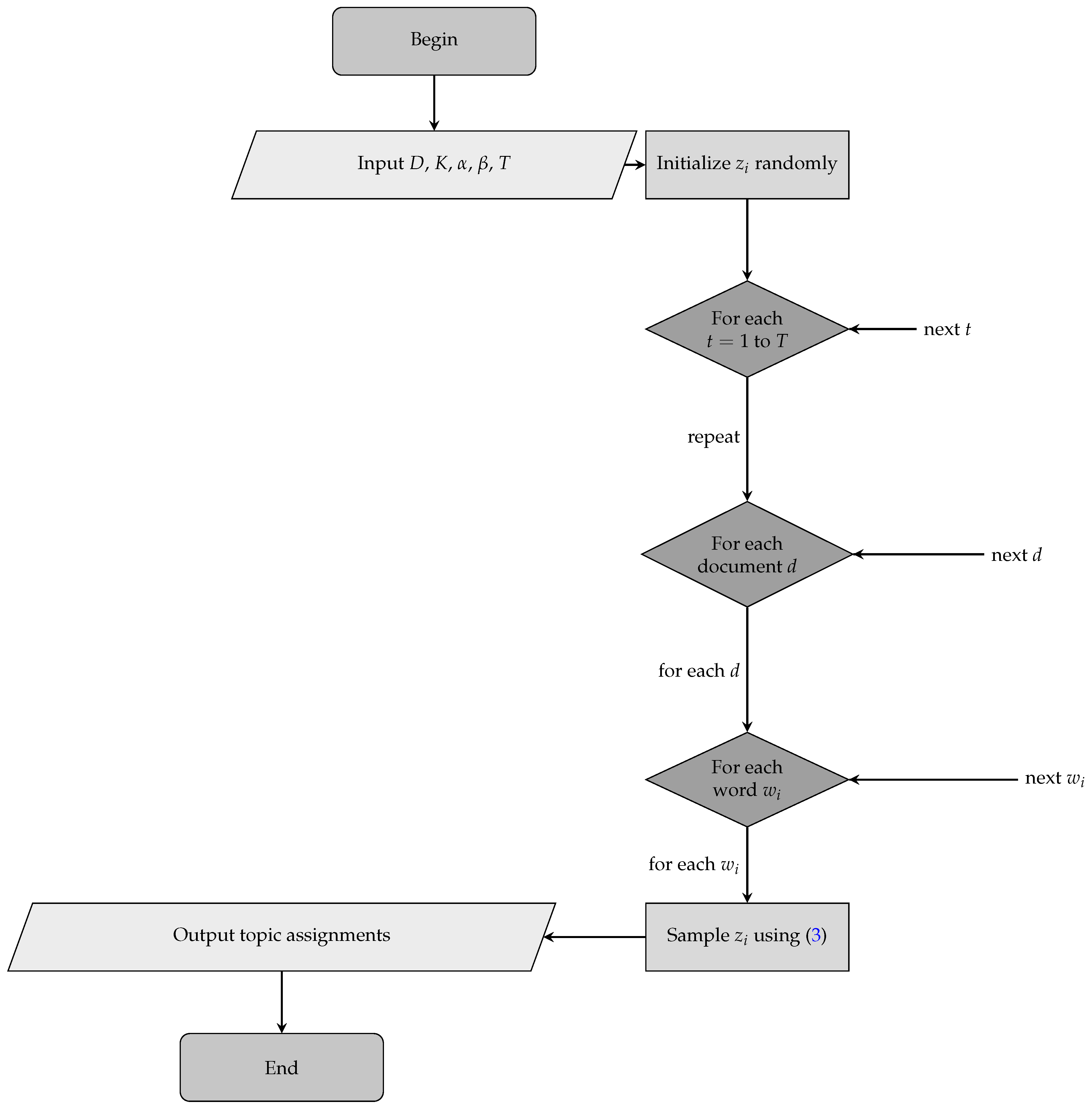

3.6. Latent Dirichlet Allocation for Topic Modeling

- 1.

- Draw document length .

- 2.

- Draw topic mixture .

- 3.

- For each word position :

- (a)

- Draw topic .

- (b)

- Draw word .

3.7. Collapsed Gibbs Sampling

| Algorithm 3: Collapsed Gibbs sampling for LDA |

|

3.8. Model Selection: Coherence and Perplexity

3.9. Implementation Details in R

- bibliometrix for metadata extraction and basic bibliometric summaries;

- igraph for graph objects, metrics, and community detection;

- ggraph + ggplot2 for visualization;

- tidytext/text2vec for text preprocessing and LDA;

- topicmodels/lda for LDA and Gibbs sampling (or custom Gibbs implementation for greater control);

- SnowballC and tm for stemming/token filtering.

| Algorithm 4: Implementation method (R pseudocode) |

|

4. Empirical Results

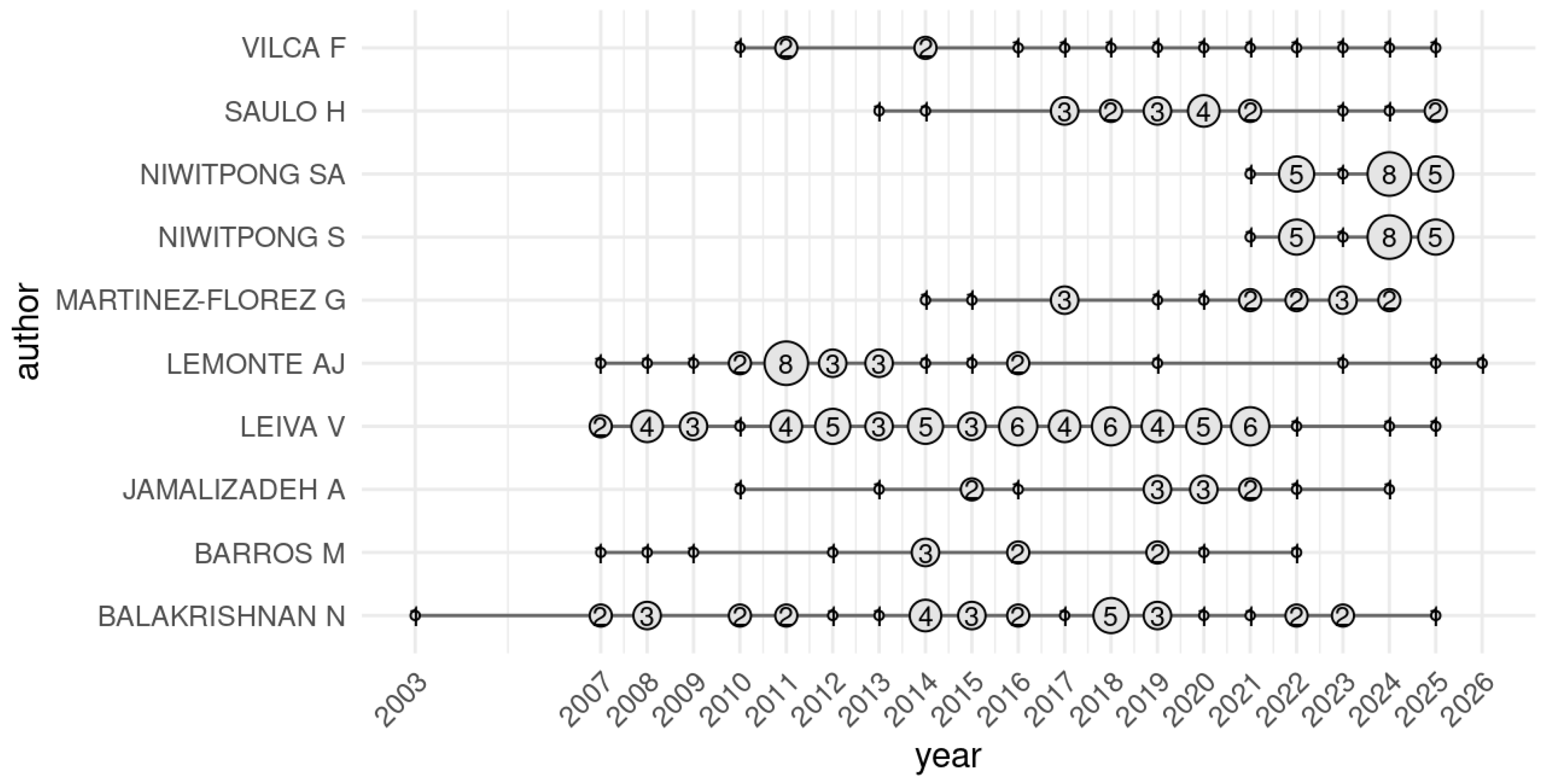

4.1. Systematic Review

4.2. Descriptive Profile of the Corpus

4.3. Network Analysis

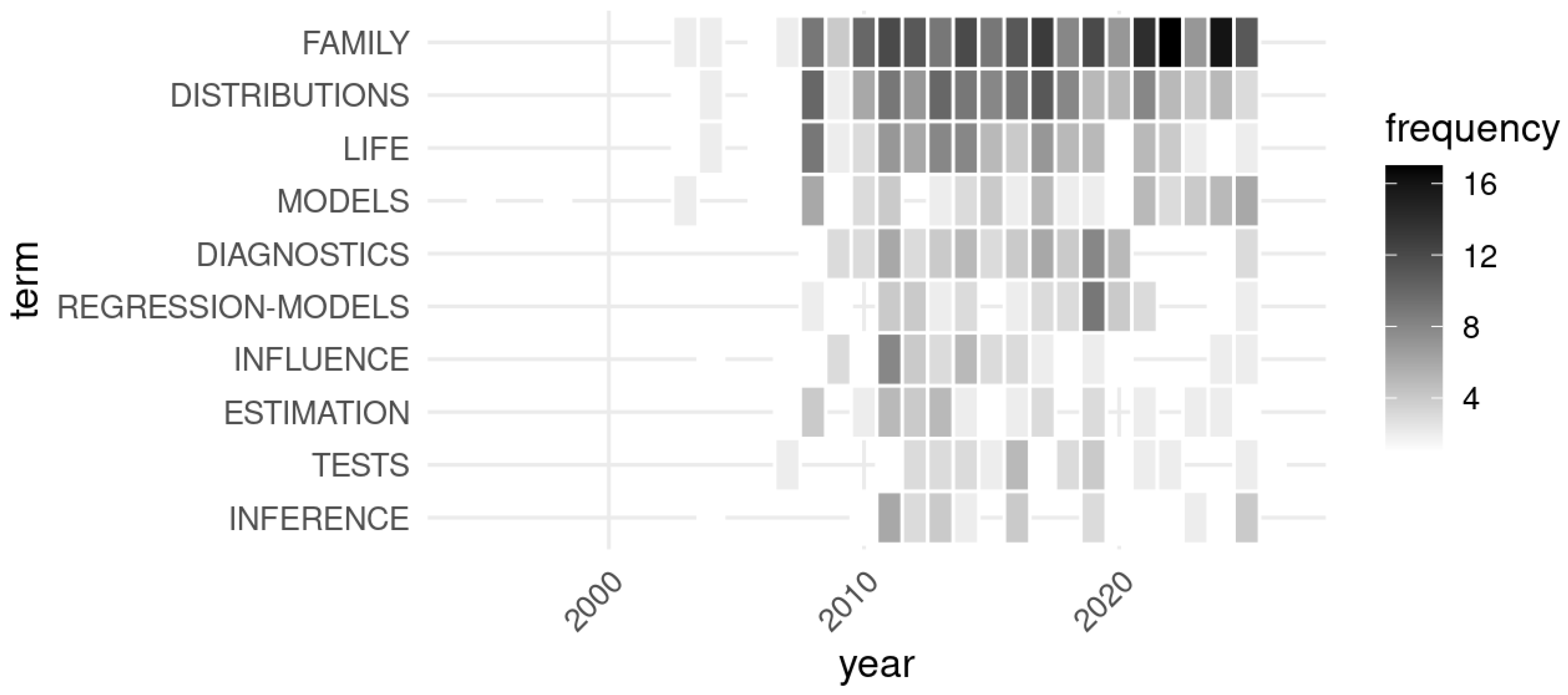

4.4. Thematic Analysis of Keywords

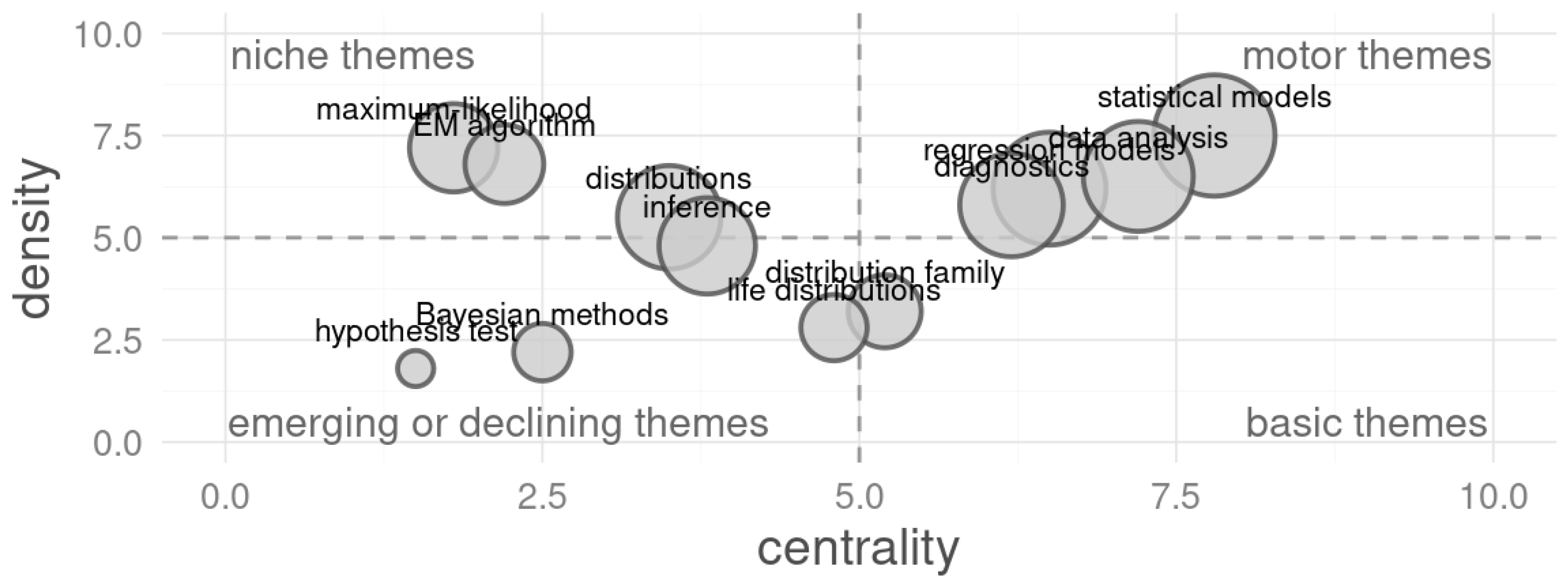

- First quadrant (upper right-motor themes)—This quadrant is primarily characterized by themes such as statistical models, data analysis, regression models, and diagnostics. These themes are well-developed (high density) and highly influential (high centrality) within the field. Their pivotal role as core structural themes drives the research progress in this domain.

- Second quadrant (upper left-niche themes)—Featuring terms like maximum likelihood, EM algorithm and distributions inference, this quadrant highlights specialized areas with strong internal connections (high density) but low centrality to the broader network. These themes represent specific computational procedures and methodological backbones that are highly detailed but operate somewhat independently of the field’s most central topics.

- Third quadrant (lower left-emerging or declining themes)—This quadrant includes hypothesis test and Bayesian methods. Situated in the area of low centrality and low density, these themes may represent foundational methodologies that are either losing specific research focus in favor of more complex algorithms, or are niche applications that have not yet gained broad traction in the current bibliometric landscape.

- Fourth quadrant (lower right-basic themes)—This quadrant, which contains topics such as life distributions and distribution family closer to the center, is intended to house themes that are fundamental and essential for the field structure (high centrality) but are less developed (low density). They are the transversal groundwork upon which more specialized and motor themes are built.

5. Unveiling Thematic Structures: Topic Modeling Implementation

5.1. Model Setup and Text Corpus Processing

- Uniformity enforcement—Converting all characters to lowercase to ensure textual consistency across the document set.

- Noise elimination—Removing punctuation, numerical data, and standard English stopwords to isolate content-bearing terms.

- Matrix generation—Forming the document-term matrix based on term frequencies, which is the requisite input for LDA.

5.2. Synthesis of Latent Topics and Network Modules

- Topic I (engineering failure)—This theme primarily reflects the concepts within Cluster 1, emphasizing long-term material resilience and damage assessment. Key terms like fatigue and life prediction highlight the primary focus on structural integrity preservation.

- Topic II (lifetime data modeling)—This theme crosses Modules 2 and 4, concentrating on mathematical frameworks for reliability engineering. The integration of statistical distributions and regression analysis underscores the use of analytical tools for modeling observed data across various conditions.

- Topic III (BS distribution inference)—Strongly tied to Module 2, this topic is dedicated to robust parameter estimation. Emphasis on maximum, likelihood, and estimation reflects the sophisticated statistical procedures used for reliability assessment concerning the BS distribution.

- Topic IV (computational methods)—Aligned with Modules 2 and 4, this topic bridges computation and forecasting. It focuses heavily on simulation techniques like Monte Carlo alongside general model estimation, crucial for anticipating component behavior.

- Topic V (advanced models)—Exhibits a robust connection with Modules 2 and 4, highlighting generalized statistical paradigms. The necessity for precise estimation methods and reliable confidence interval determination is a central technical focus here.

- Topic VI (forecasting)—Directly linked to Module 1, this reinforces the engineering basis of the study. Recurring vocabulary like cumulative damage and life prediction indicates a foundational research stream focused on anticipating material failure modes.

| Topic | Label | Terms |

|---|---|---|

| I | Engineering failure | cumulative damage; fatigue; life prediction |

| II | Lifetime data modeling | lifetime; regression analysis; statistical distributions |

| III | BS distribution inference | censoring; estimation method; |

| maximum likelihood; robustness | ||

| IV | Computational methods | model estimation; monte carlo; simulation |

| V | Advanced models | confidence interval; estimation methods; influence diagnostics; |

| multivariate models; regression models; | ||

| VI | Forecasting | accelerated life models; cumulative damage; diagnostics |

| life prediction; regression |

6. Final Synthesis and Outlook for the Birnbaum–Saunders Field

6.1. Key Findings Organized by Research Questions

- RQ1 [Advances in BS theory and methods] The core focus of theoretical development centers on generating robust statistical extensions for the BS family. Major methodological leaps encompass the refinement of Bayesian methods, the implementation of shrinkage estimators, and the creation of regression frameworks suitable for grouped or hybrid censored data. Furthermore, specialized contexts involving ordered set sampling, frailty concepts, and spatial/autoregressive structures have seen model adaptation. The necessity for strong inferential capacity is met through sophisticated influence diagnostics and bivariate modeling strategies.

- RQ2 [Practical impact and domain applications] The primary utility of the BS distribution remains in lifetime data evaluation and the forecasting of material failure (such as in fatigue contexts). However, its adoption has diversified significantly, now proving valuable across fields such as biological mortality studies, environmental forecasting, medical statistics, neural signal processing, and complex financial/risk models (including, for instance, insurance risk and power generation estimation).

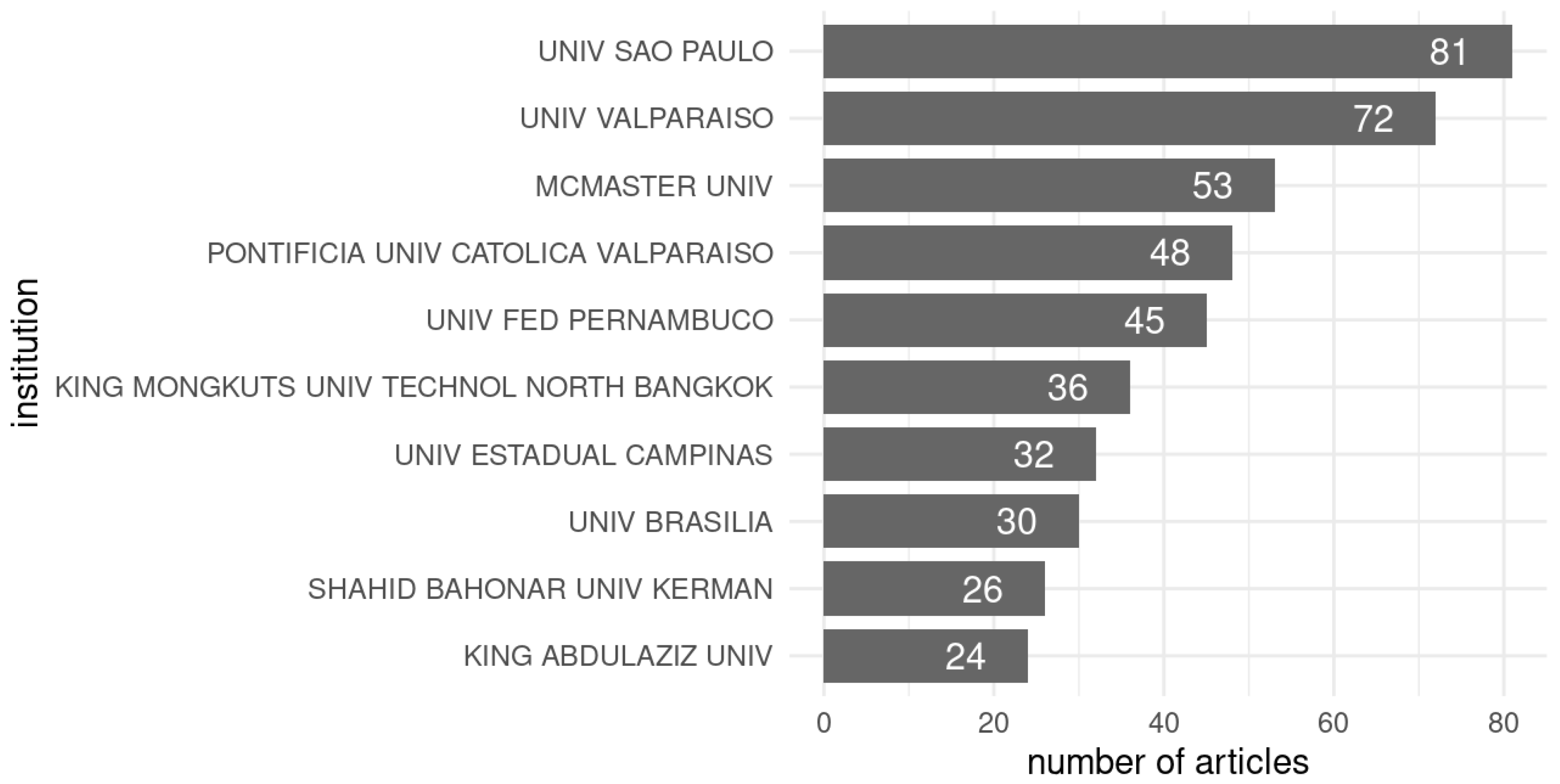

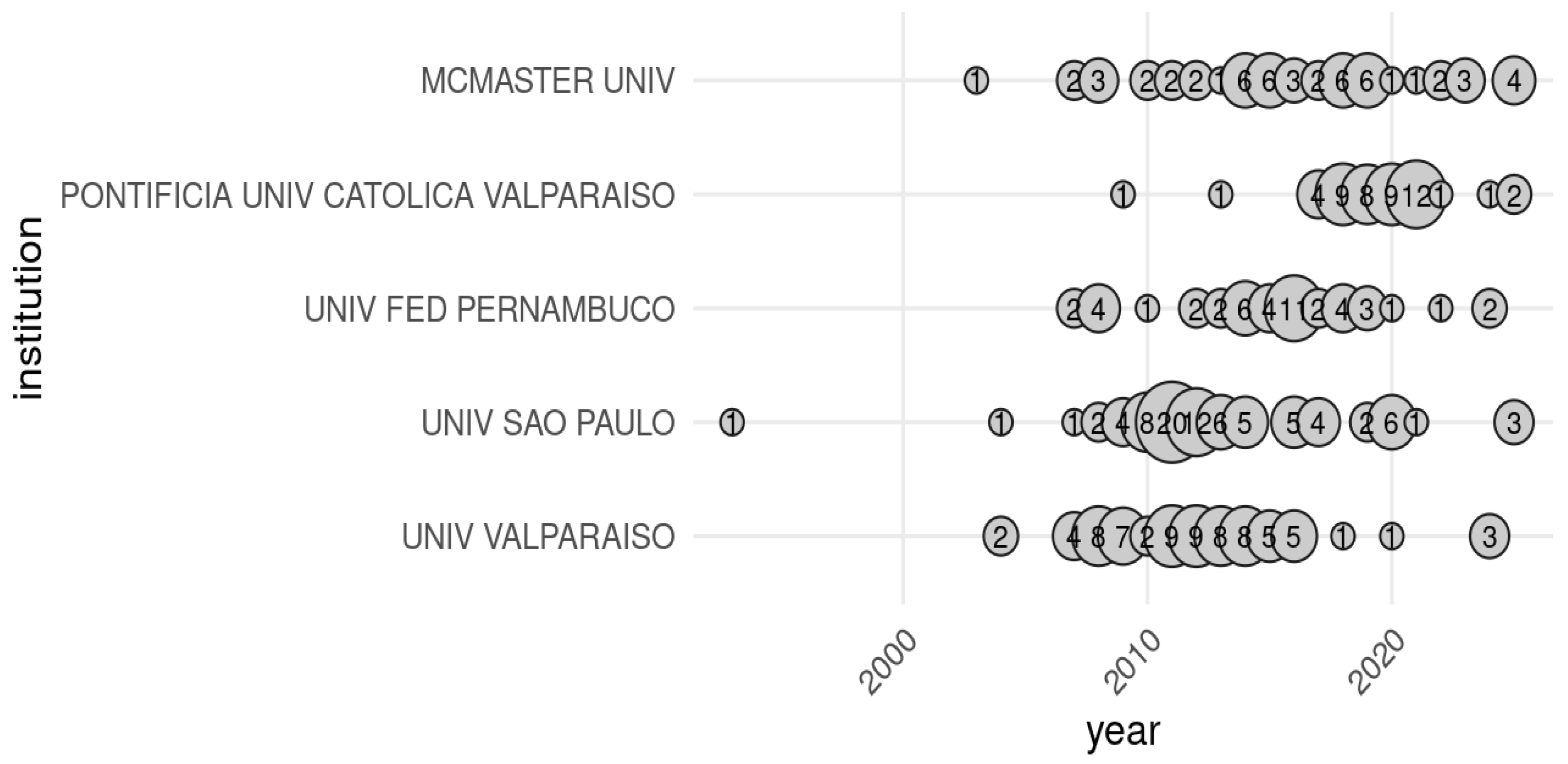

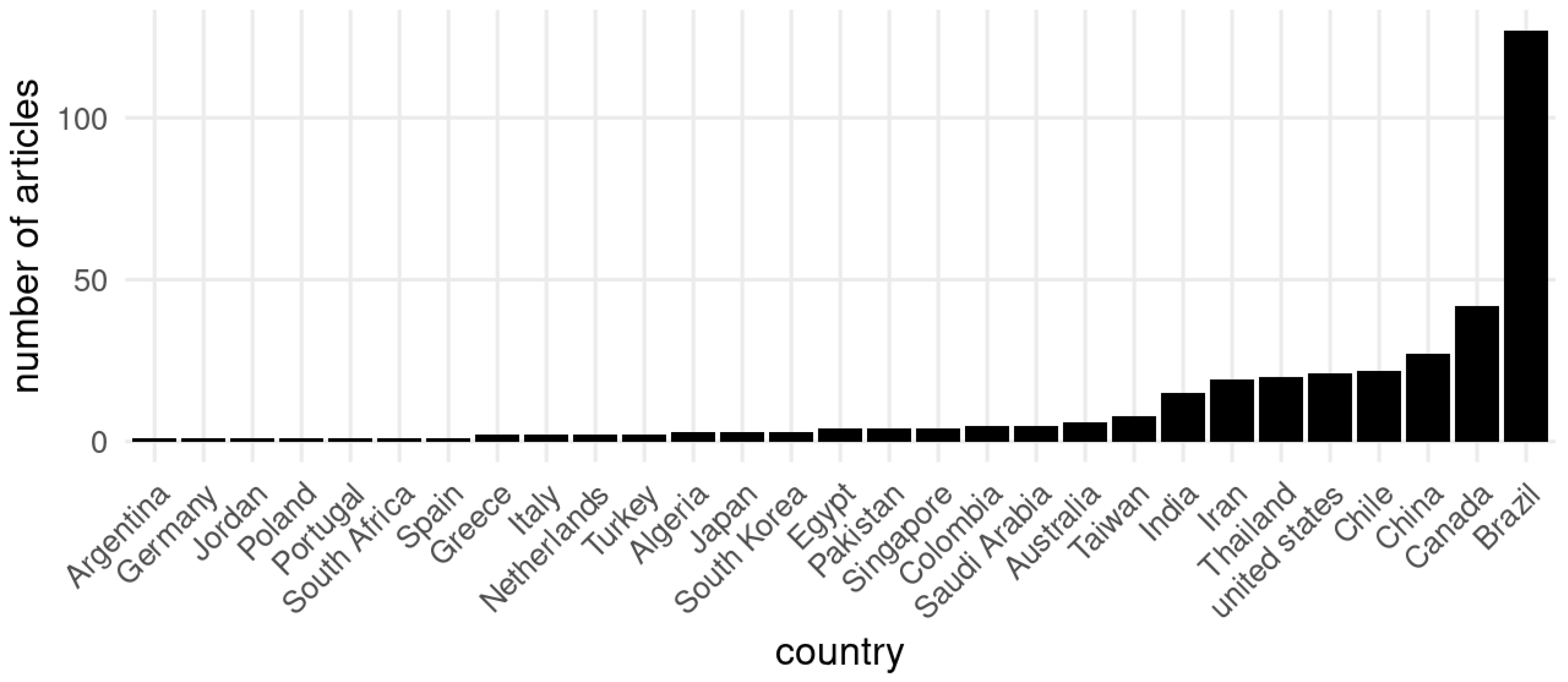

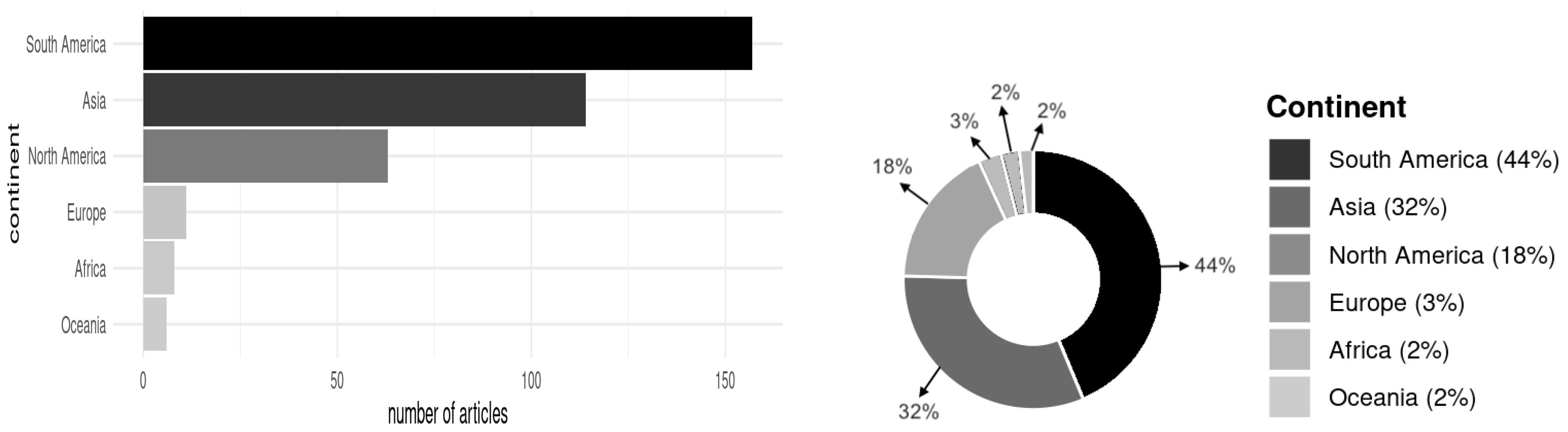

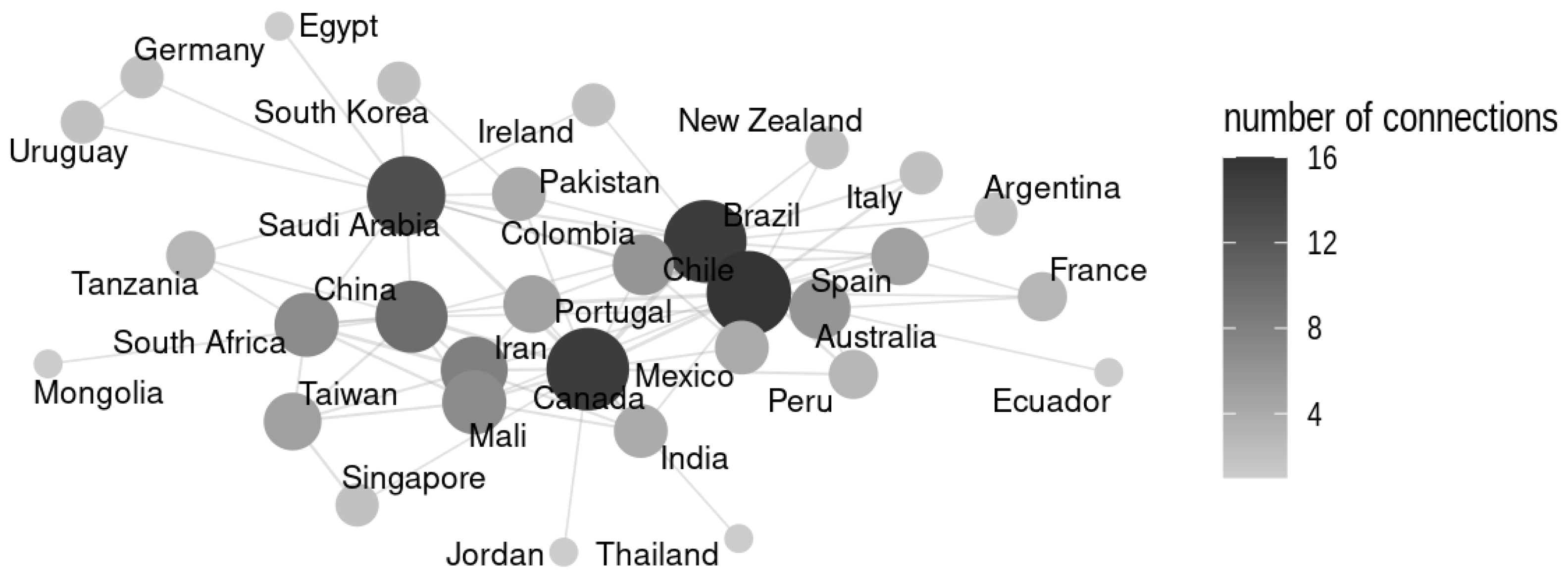

- RQ3 [Structural characteristics and gaps in the literature] The field is characterized by a substantial output of original research articles (over 350 works examined), with the highest frequency of publications recorded near 2019. The collaboration landscape reveals significant international partnerships, most notably the strong axis between Brazil and Chile. Concerning dissemination, the journal Computational Statistics and Data Analysis stands out as an exceptionally influential publication venue. A critical deficiency noted is the scarcity of structured review papers and the need for user-friendly, auditable software tools.

- RQ4 [Trajectories for future research] The analytical results strongly suggest that future efforts should prioritize advanced BS model development, software creation, and comprehensive diagnostic toolkits. It is crucial to translate theoretical findings into established practical decision-making criteria for applied teams. Methodologically, exploring frontiers such as dynamic or neural topic modeling is highly recommended to extract subtler insights from the evolving thematic structure of the literature.

6.2. Summary of Analysis and Research Contributions

6.3. Caveats and Future Trajectories

- Corpus expansion—Broadening the literature base to include diverse databases for a more exhaustive perspective.

- Temporal dynamics—Executing a longitudinal analysis to track the evolution of thematic interest and methodological shifts over time.

- Interdisciplinary synergy—Encouraging research that bridges statistical methods with specialized engineering or domain-specific fields to unlock novel solutions.

- Methodological sophistication—Deploying next-generation analytical techniques, such as dynamic or neural topic modeling, to gain even richer structural insights.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birnbaum, Z.W.; Saunders, S.C. A new family of life distributions. J. Appl. Probab. 1969, 6, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, Z.W.; Saunders, S.C. Estimation for a family of life distributions with applications to fatigue. J. Appl. Probab. 1969, 6, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, C.; Paula, G.A.; Leiva, V. Birnbaum-Saunders mixed models for censored reliability data analysis. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2011, 60, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiraud, P.; Leiva, V.; Fierro, R. A non-central version of the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution for reliability analysis. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2009, 58, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, N. Statistical inference for progressive stress accelerated life testing with Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Stats 2018, 1, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, X. A novel random-effect Birnbaum–Saunders distribution for reliability assessment considering accelerated mechanism equivalence. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2025, 22, 752–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, Z.W.; Saunders, S.C. A probabilistic interpretation of Miner’s rule. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1968, 16, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonte, A.J.; Cribari-Neto, F.; Vasconcellos, K.L. Improved statistical inference for the two-parameter Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 51, 4656–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, L.S.; Cysneiros, A.H.M.A.; Cribari-Neto, F. Improved Birnbaum–Saunders inference under type II censoring. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2013, 57, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Cribari-Neto, F. Hypothesis testing in log-Birnbaum–Saunders regressions. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2017, 46, 3990–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, N. A new inference approach for type-II generalized Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Stats 2019, 2, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalath, K.P. Fiducial inference on the right censored Birnbaum–Saunders data via Gibbs sampler. Stats 2021, 4, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, R.V.; Cribari-Neto, F. Inference in a bimodal Birnbaum–Saunders model. Math. Comput. Simul. 2018, 146, 134–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, L.; Vilca, F.; Leiva, V. Influence analysis in skew-Birnbaum-Saunders regression models and applications. J. Appl. Stat. 2011, 38, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, M.; Gallardo, D.I. A new look at the Birnbaum–Saunders regression model. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2022, 38, 935–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, S.; Altaf, S. Addressing multicollinearity in log-Birnbaum–Saunders regression model: A ridge regression estimation approach. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2025, 20, 6997–7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.; Galea, M.; Leiva, V.; Paula, G.A. Influence diagnostics in the tobit censored response model. Stat. Methods Appl. 2010, 19, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto, F.; Fonseca, R.V. A new log-linear bimodal Birnbaum–Saunders regression model with application to survival data. Braz. J. Probab. Stat. 2019, 33, 329–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, N.M.; Martinez-Florez, G.; Bolfarine, H. Bimodal Birnbaum–Saunders distribution with applications to non negative measurements. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2017, 46, 6240–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, V. The Birnbaum-Saunders Distribution; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, N.; Kundu, D. Birnbaum-Saunders distribution: A review of models, analysis, and applications. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2018, 35, 4–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, V.; Ferreira, M.; Gomes, M.I.; Lillo, C. Extreme value Birnbaum-Saunders regression models applied to environmental data. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016, 30, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.I.; Barros, M.; Campos, J.; Cysneiros, F.J.A. Bivariate Birnbaum–Saunders accelerated lifetime model: Estimation and diagnostic analysis. J. Appl. Stat. 2022, 49, 1252–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Florez, G.; Olmos, N.M.; Venegas, O. Unit-bimodal Birnbaum–Saunders distribution with applications. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2024, 53, 2173–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Florez, G.; Bolfarine, H.; Gomez, Y.M.; Gomez, H.W. A unification of families of Birnbaum–Saunders distributions with applications. REVSTAT-Stat. J. 2020, 18, 637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Florez, G.; Azevedo-Farias, R.B.; Moreno-Arenas, G. Multivariate log-Birnbaum–Saunders regression models. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2017, 46, 10166–10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazucheli, M.; Menezes, A.F.B.; Dey, S. The unit-Birnbaum-Saunders distribution with applications. Chil. J. Stat. 2018, 9, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.E.; Castro-Kuriss, C.; Flores, E.; Leiva, V.; Sanhueza, A. A truncated version of the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution with an application in financial risk. Pak. J. Stat. 2010, 26, 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, K.L.P.; Castro, B.S.; Saulo, H.; Vila, R. On a length-biased Birnbaum–Saunders regression model applied to meteorological data. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2023, 52, 6916–6935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.; Vilca, F.; Gallardo, D.I.; Gomez, H.W. Modified slash Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Hacet. J. Math. Stat. 2017, 46, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.M.; Soares de Lima, M.C.; Ortega, E.M.M.; Suzuki, A.K. A new extended Birnbaum–Saunders model: Properties, regression and applications. Stats 2018, 1, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B.C.; Gallardo, D.I.; Gomez, H.W. A new bivariate Birnbaum–Saunders type distribution based on the skew generalized normal model. REVSTAT-Stat. J. 2023, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, R.; Saulo, H.; Quintino, F.; Zoernig, P. A new unit-bimodal distribution based on correlated Birnbaum–Saunders random variables. Comput. Appl. Math. 2025, 44, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorea, C.C.Y.; Vila, R.; Castro, C.; Leiva, V.; Quintino, F.S. Revisiting fatigue-life distributions of Birnbaum–Saunders type: Mathematical characterization, simulation study, and applications. Appl. Math. Model. 2025, 147, 116223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bdair, O.M. Inference for two-parameter Birnbaum-Saunders distribution based on type-II censored data. Mathematics 2025, 13, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.G.; Park, D.; Lee, W. Objective Bayesian inference for Birnbaum-Saunders distributions. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, W.; Ahmad, A.; Ali, S. Advancements in shrinkage estimation for the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. J. Sci. Res. 2025, 17, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.K.; Aslam, M. Birnbaum-Saunders distribution for imprecise data under neutrosophic environment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawlan, Z.; Scavino, M.; Tempone, R. Modeling metallic fatigue data using the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. Metals 2024, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmkhah, M.; Arashi, M.; Bekker, A.; Marques, F.J. Neutrosophic Birnbaum–Saunders distribution with applications. Appl. Math. Model. 2026, 149, 116287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahhat, A.; Alotaibi, R.; Nassar, M. Statistical inference of the Birnbaum–Saunders model using adaptive progressively hybrid censored data and its applications. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 11092–11121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, R. Birnbaum–Saunders parameters estimation using simple random sampling and ranked set sampling. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2025, 54, 3624–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, D.I.; Bourguignon, M.; Romeo, J.S. Birnbaum–Saunders frailty regression models for clustered survival data. Stat. Comput. 2024, 34, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasilva, A.; Saulo, H.; Vila, R.; Pal, S. Scale-mixture Birnbaum–Saunders quantile regression models applied to personal accident insurance data. Comput. Appl. Math. 2025, 44, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuyuguchi, A.B.; Paula, G.A.; Barros, M. Analysis of correlated Birnbaum–Saunders data based on estimating equations. TEST 2020, 29, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, J.N.; Barreto-Souza, W.; Ombao, H. Poisson–Birnbaum–Saunders regression model for clustered count data. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2024, 18, 3338–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janthasuwan, U.; Niwitpong, S.; Niwitpong, S. Generalized confidence interval for the common coefficient of variation of several zero-inflated Birnbaum–Saunders distributions with an application to wind speed data. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 2697–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, C.R. The Birnbaum-Saunders autoregressive conditional duration model. Math. Comput. Simul. 2010, 80, 2062–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, R.V.; Cribari-Neto, F. Bimodal Birnbaum–Saunders generalized autoregressive score model. J. Appl. Stat. 2018, 45, 2585–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulo, H.; Leao, J.; Leiva, V.; Aykroyd, R.G. Birnbaum-Saunders autoregressive conditional duration models applied to high-frequency financial data. Stat. Pap. 2019, 60, 1605–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Papani, F.; Uribe-Opazo, M.A.; Leiva, V.; Aykroyd, R.G. Birnbaum-Saunders spatial modelling and diagnostics applied to agricultural engineering data. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2017, 31, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, M.; Ho, L.L.; Fernandes, F.H. Control charts for monitoring the median parameter of Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2020, 36, 1333–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.C.; Wu, S.J.; Lin, T.I. Pollution concentration monitoring using a new Birnbaum-Saunders control chart. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2024, 40, 3913–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Aslam, M.; Noor, Z. CUSUM charts utilizing reparametrized Birnbaum-Saunders models. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2024, 58, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangjai, W.; Janthasuwan, U.; Niwitpong, S.A. Estimation of the percentile of Birnbaum-Saunders distribution and its application to PM2.5. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janthasuwan, U.; Niwitpong, S.A.; Wongkhao, A. Confidence intervals for the coefficient of variation of Delta-Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 37159–37179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vega, D.; Vilca, F.; Zeller, C.B.; Balakrishnan, N. A leptokurtic-form Birnbaum-Saunders distribution with applications to finance. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2025, 41, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.M.A. Change point estimation of hazard rates in contaminated Birnbaum-Saunders models with an application to tuberculosis survival data. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 26106–26131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, V.; Saunders, S.C. Cumulative damage models. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Leiva, V.; Castro, C.; Vila, R.; Saulo, H. Unveiling patterns and trends in research on cumulative damage models for statistical and reliability analyses: Bibliometric and thematic explorations with data analytics. Chil. J. Stat. 2024, 15, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Chakraborty, S. Inflated log-Lindley distribution for modeling continuous data bounded in unit interval with possible mass at boundaries. Chil. J. Stat. 2023, 14, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.M.; Rodrigues, G.M.; Ortega, E.M.M.; de Santana, L.H.; Vila, R. An extended Rayleigh model: Properties, regression and COVID-19 application. Chil. J. Stat. 2023, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.M.; Biazatti, E.C.; Ortega, E.M.M.; de Lima, M.C.S.; de Santana, L.H. The Weibull flexible generalized family of bimodal distributions: Properties, simulation, regression models, and applications. Chil. J. Stat. 2024, 15, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Kotz, S.; Leiva, V.; Sanhueza, A. Two new mixture models related to the inverse Gaussian distribution. Methodol. Comput. Appl. Probab. 2010, 12, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, G.K.; Fries, A. Fatigue failure models and Birnbaum-Saunders vs. inverse Gaussian. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1982, 31, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, D.; Kannan, N.; Balakrishnan, N. On the hazard function of Birnbaum–Saunders distribution and associated inference. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 52, 2692–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, C.; Leiva, V.; Athayde, E.; Balakrishnan, N. Shape and change point analyses of the Birnbaum-Saunders-t hazard rate and associated estimation. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2012, 56, 3887–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Leiva, V.; Hernández, H.; Riquelme, M. A new package for the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. R J. 2006, 6, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, M.; Paula, G.A.; Leiva, V. An R implementation for generalized Birnbaum-Saunders distributions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 1511–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, A.K.M.; Pedapati, S.R.; Muhammad, M.; Leiva, V. Overview of explainable artificial intelligence for prognostic and health management of industrial assets based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Sensors 2021, 21, 8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. How to normalize co-occurrence data? An analysis of some well-known similarity measures. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1635–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Comput. Netw. 1998, 30, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Laville, F. Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics 1991, 22, 155–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Inf. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, N.; Leiva, V.; López, J. Acceptance sampling plans from truncated life tests based on the generalized Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2007, 36, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieck, J.R.; Nedelman, J.R. A log-linear model for the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. Technometrics 1991, 33, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, H.K.T.; Kundu, D.; Balakrishnan, N. Modified moment estimation for the two-parameter Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2003, 43, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, M.; Bain, L.J.; Wright, F.T. Inferences on the parameters of the Birnbaum-Saunders fatigue life distribution based on maximum likelihood estimation. Technometrics 1981, 23, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.M.; Lemonte, A.J. The β-Birnbaum-Saunders distribution: An improved distribution for fatigue life modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2011, 55, 1445–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, V.; Barros, M.; Paula, G.A.; Galea, M. Influence diagnostics in log-Birnbaum-Saunders regression models with censored data. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2007, 51, 5694–5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, K.; Alavi, O.; McGowan, J.G. Use of Birnbaum-Saunders distribution for estimating wind speed and wind power probability distributions: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 143, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lio, Y.L.; Tsai, T.R.; Wu, S.J. Acceptance sampling plans from truncated life tests based on the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution for percentiles. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2009, 39, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, G.A.; Leiva, V.; Barros, M.; Liu, S. Robust statistical modeling using the Birnbaum-Saunders-t distribution applied to insurance. Appl. Stoch. Model. Bus. Ind. 2012, 28, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, H.W.; Olivares-Pacheco, J.F.; Bolfarine, H. An extension of the generalized Birnbaum-Saunders distribution. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2009, 79, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhueza, A.; Leiva, V.; Balakrishnan, N. The generalized Birnbaum–Saunders distribution and its theory, methodology, and application. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2008, 37, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baklizi, A.; El Qader El Masri, A. Acceptance sampling based on truncated life tests in the Birnbaum-Saunders model. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, V.; Marchant, C.; Saulo, H.; Aslam, M.; Rojas, F. Capability indices for Birnbaum-Saunders processes applied to electronic and food industries. J. Appl. Stat. 2014, 41, 1881–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Kundu, D. Inference and optimal censoring schemes for progressively censored Birnbaum–Saunders distribution. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2013, 143, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, M.; Leiva, V.; Paula, G. Influence diagnostics in log-Birnbaum-Saunders regression models. J. Appl. Stat. 2004, 31, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, B.; Hornik, K. topicmodels: An R package for fitting topic models. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 40, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.L.; Steyvers, M. Finding scientific topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5228–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Xia, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S. A density-based method for adaptive LDA model selection. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzintcev, N. ldatuning: Tuning of the Latent Dirichlet Allocation Models Parameters. R Package Version 0.2.0. 2016. Available online: https://rdrr.io/cran/ldatuning/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

| Year | Number of Articles | Year | Number of Articles | Year | Number of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1 | 2001 | 1 | 2015 | 12 |

| 1981 | 2 | 2003 | 4 | 2016 | 19 |

| 1982 | 2 | 2004 | 3 | 2017 | 16 |

| 1987 | 1 | 2006 | 3 | 2018 | 16 |

| 1991 | 1 | 2007 | 5 | 2019 | 31 |

| 1993 | 2 | 2008 | 10 | 2020 | 21 |

| 1994 | 3 | 2009 | 6 | 2021 | 25 |

| 1995 | 2 | 2010 | 11 | 2022 | 23 |

| 1997 | 1 | 2011 | 17 | 2023 | 16 |

| 1998 | 1 | 2012 | 14 | 2024 | 28 |

| 1999 | 2 | 2013 | 12 | 2025 | 23 |

| 2000 | 1 | 2014 | 13 | 2026 | 2 |

| Journal | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Computational Statistics and Data Analysis | 33 |

| Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation | 26 |

| Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry | 23 |

| Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation | 20 |

| Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods | 20 |

| Journal of Applied Statistics | 17 |

| IEEE Transactions on Reliability | 12 |

| Mathematics | 12 |

| Symmetry | 11 |

| Brazilian Journal of Probability and Statistics | 8 |

| Authors | Title | Journal | Year | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balakrishnan N; Leiva V; Lopez J [79] | Acceptance sampling plans from truncated life tests based on the generalized Birnbaum-Saunders distribution | Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation | 2007 | 221 |

| Rieck JR; Nedelman JR [80] | A log linear-model for the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution | Technometrics | 1991 | 192 |

| Ng HKT; Kundu D; Balakrishnan N [81] | Modified moment estimation for the two-parameter Birnbaum-Saunders distribution | Computational Statistics and Data Analysis | 2003 | 163 |

| Engelhardt M; Bain LJ; Wright FT [82] | Inferences on the parameters of the Birnbaum-Saunders fatigue life distribution based on maximum-likelihood estimation | Technometrics | 1981 | 113 |

| Kundu D; Kannan N; Balakrishnan N [68] | On the hazard function of Birnbaum-Saunders distribution and associated inference | Computational Statistics and Data Analysis | 2008 | 109 |

| Cordeiro GM; Lemonte AJ [83] | The -Birnbaum-Saunders distribution, an improved distribution for fatigue life modeling | Computational Statistics and Data Analysis | 2011 | 108 |

| Leiva V; Barros M; Paula GA; Galea M [84] | Influence diagnostics in log-Birnbaum-Saunders regression models with censored data | Computational Statistics & Data Analysis | 2007 | 108 |

| Balakrishnan N; Kundu D [21] | Birnbaum-Saunders distribution: A review of models, analysis, and applications | Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry | 2019 | 104 |

| Mohammadi K; Alavi O; Mcgowan JG [85] | Use of Birnbaum-Saunders distribution for estimating wind speed and wind power probability distributions: a review | Energy Conversion and Management | 2017 | 100 |

| Leiva V; Barros M; Paula GA; Sanhueza A [72] | Generalized Birnbaum-Saunders distributions applied to air pollutant concentration | Environmetrics | 2008 | 97 |

| Lio Yl; Tsai TR; Wu SJ [86] | Acceptance sampling plans from truncated life tests based on the Birnbaum-Saunders distribution for percentiles | Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation | 2010 | 96 |

| Lemonte AJ; Cribari-Neto F; Vasconcellos KL [8] | Improved statistical inference for the two-parameter Birnbaum-Saunders distribution | Computational Statistics and Data Analysis | 2007 | 93 |

| Paula GA; Leiva V; Barros M; Liu S [87] | Robust statistical modeling using the Birnbaum-Saunders-t distribution applied to insurance | Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry | 2012 | 90 |

| Gomez HW; Olivares-Pacheco JF; Bolfarine H [88] | An extension of the generalized Birnbaum-Saunders distribution | Statistics and Probability Letters | 2009 | 89 |

| Sanhueza A; Leiva V; Balakrishnan N [89] | The generalized Birnbaum-Saunders distribution and its theory, methodology, and application | Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods | 2008 | 85 |

| Bhattacharyya GK; Fries A [67] | Fatigue failure models - Birnbaum-Saunders vs inverse Gaussian | IEEE Transactions on Reliability | 1982 | 83 |

| Baklizi A; El Masri AE [90] | Acceptance sampling based on truncated life tests in the Birnbaum Saunders model | Risk Analysis | 2004 | 80 |

| Leiva V; Marchant C; Saulo H; Aslam M; Rojas F [91] | Capability indices for Birnbaum-Saunders processes applied to electronic and food industries | Journal of Applied Statistics | 2014 | 77 |

| Pradhan B; Kundu D [92] | Inference and optimal censoring schemes for progressively censored Birnbaum-Saunders distribution | Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference | 2013 | 77 |

| Galea M; Leiva V; Paula GA [93] | Influence diagnostics in log-Birnbaum-Saunders regression models | Journal of Applied Statistics | 2004 | 77 |

| Country | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Brazil | 129 |

| Chile | 82 (22) |

| Canada | 42 |

| China | 28 |

| Thailand | 21 |

| United States | 21 |

| Iran | 19 |

| India | 15 |

| Taiwan | 8 |

| Australia | 6 |

| Saudi Arabia | 6 |

| Colombia | 5 |

| Egypt | 4 |

| Pakistan | 4 |

| Singapore | 4 |

| Algeria | 3 |

| Italy | 3 |

| Japan | 3 |

| South Korea | 3 |

| Greece | 2 |

| Netherlands | 2 |

| Turkey | 2 |

| Argentina | 1 |

| Germany | 1 |

| Jordan | 1 |

| Poland | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 |

| South Africa | 1 |

| Spain | 1 |

| Continent | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 8 | 2.23 |

| Asia | 114 | 31.75 |

| Europe | 11 | 3.06 |

| North America | 63 | 17.55 |

| Oceania | 6 | 1.67 |

| South America | 157 | 43.73 |

| Country Pair | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Brazil–Chile | 57 |

| Iran–Mali | 17 |

| Brazil–Colombia | 14 |

| Brazil–Canada | 12 |

| Chile–Colombia | 12 |

| Canada–China | 8 |

| Canada–India | 8 |

| Canada–Saudi Arabia | 8 |

| Chile–Portugal | 8 |

| Canada–Chile | 7 |

| Iran–South Africa | 7 |

| Chile–Spain | 6 |

| Chile–Italy | 5 |

| Brazil–Peru | 4 |

| Brazil–Saudi Arabia | 4 |

| Canada–Iran | 4 |

| Canada–Mali | 4 |

| Mali–South Africa | 4 |

| Singapore–Taiwan | 4 |

| Australia–Brazil | 3 |

| Keyword | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Birnbaum–Saunders distribution | 7.36% |

| likelihood methods | 3.10% |

| interval estimation | 2.64% |

| lifetime data | 2.18% |

| fatigue life distribution | 2.12% |

| EM algorithm | 1.24% |

| distribution | 1.14% |

| Monte Carlo simulation | 1.09% |

| R software | 1.09% |

| sinh-normal (log-BS) distribution | 0.62% |

| bootstrap | 0.62% |

| estimation | 0.62% |

| simulation | 0.57% |

| kurtosis | 0.52% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leiva, V. Mapping Research on the Birnbaum–Saunders Statistical Distribution: Patterns, Trends, and Scientometric Perspective. Stats 2025, 8, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8040116

Leiva V. Mapping Research on the Birnbaum–Saunders Statistical Distribution: Patterns, Trends, and Scientometric Perspective. Stats. 2025; 8(4):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8040116

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeiva, Víctor. 2025. "Mapping Research on the Birnbaum–Saunders Statistical Distribution: Patterns, Trends, and Scientometric Perspective" Stats 8, no. 4: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8040116

APA StyleLeiva, V. (2025). Mapping Research on the Birnbaum–Saunders Statistical Distribution: Patterns, Trends, and Scientometric Perspective. Stats, 8(4), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/stats8040116