1. Introduction

Persistent racial and ethnic disparities in cancer survival outcomes represent one of the most pressing challenges in contemporary public health research [

1,

2,

3]. Black patients demonstrate significantly higher death rates than other racial and ethnic groups across multiple cancer types, with disparities particularly pronounced in breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancers. Recent population-based analyses reveal that while overall cancer-specific survival improved from 2004 to 2018, substantial racial disparities persist across multiple domains of care [

4,

5].

These epidemiological patterns present complex methodological challenges that extend beyond traditional survival analysis approaches. Understanding the sources of group differences in survival outcomes requires decomposition methods that can distinguish between disparities explained by measured covariates versus those attributable to unmeasured factors or differential treatment effects [

6,

7]. The Peters–Belson method provides a counterfactual framework for such decomposition, estimating what survival outcomes would be for minority group members if they experienced the same covariate effects as the majority group [

8,

9].

However, successful extension of Peters–Belson methods to survival analysis faces several fundamental challenges. First, traditional survival models may inadequately capture complex relationships between covariates and outcomes, particularly when these relationships involve high-order interactions or nonlinear effects [

10,

11]. Second, machine learning methods applied to Peters–Belson decomposition without proper validation can produce mathematically invalid counterfactual estimates that violate basic logical bounds [

12,

13]. Third, ensemble approaches may inherit failures from poorly performing individual models, contaminating the entire decomposition analysis [

14,

15]. Fourth, unmeasured confounding factors that operate at the group level may not be adequately addressed by conventional approaches [

16,

17].

This manuscript addresses four core methodological problems in survival-based health disparity research. We develop validated ensemble machine learning methods that combine multiple survival modeling approaches within the Peters–Belson framework while ensuring logical validity of counterfactual estimates through comprehensive validation procedures. Our approach incorporates transfer learning methods to discover and incorporate shared latent factors between groups that may capture unmeasured determinants of health disparities. We implement cross-validation and regularization approaches that prevent overfitting to majority group patterns while ensuring generalizability to minority group counterfactual estimation. Finally, we provide diagnostic tools and validation procedures that ensure Peters–Belson logical bounds compliance and guide method selection based on observable data characteristics.

Terminology Clarification: We use “transfer learning” in a statistical sense distinct from its common usage in machine learning. In ML, transfer learning typically refers to adapting a model pre-trained on one task/domain to a different but related task/domain. In our context, “transfer learning” refers to the transfer of covariate structure information from the pooled population (majority + minority groups) to identify latent factors that capture group-level variation not directly measured. This is accomplished through PCA on the combined covariate space, with the resulting components used to augment the Peters–Belson decomposition. This usage aligns with the broader statistical concept of learning transferable structure across populations, though it does not involve pre-trained models or domain adaptation in the ML sense.

Contributions

Our main contributions are: (1) a validated ensemble framework that extends Peters–Belson decomposition to survival analysis with comprehensive model validation ensuring logical bounds compliance; (2) development of transfer learning methods that capture group-level latent factors through principal component analysis, providing meaningful improvements when unmeasured confounding exists; (3) implementation of Peters–Belson-specific validation procedures that assess logical bounds compliance and counterfactual validity; (4) systematic evaluation across realistic health disparity scenarios demonstrating when ensemble methods versus individual approaches excel; and (5) development of diagnostic tools that characterize data complexity and provide guidance for method selection based on observable characteristics and validation results.

Ensemble machine learning methods are well-established in the statistical and machine learning literature [

14,

15]. Our contribution lies in the specific adaptation of these methods to the Peters–Belson decomposition framework for survival analysis, with particular emphasis on the validation procedures that ensure logical bounds compliance—a challenge unique to counterfactual estimation in disparity decomposition.

2. Methods

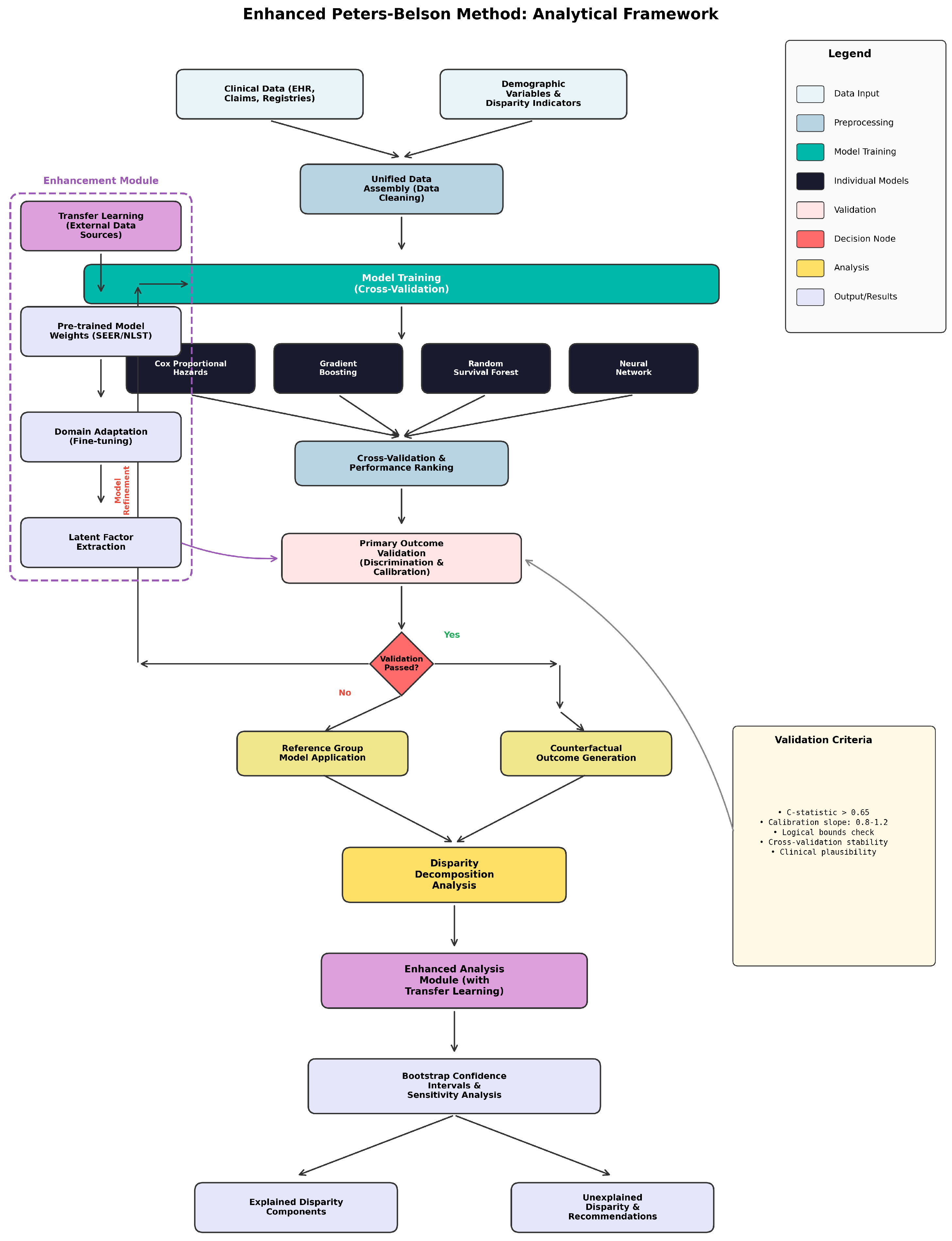

Figure 1 provides an overview of our validated ensemble Peters–Belson framework, illustrating the complete methodology from data input through individual model training, validation, ensemble construction, optional transfer learning enhancement, and final disparity decomposition analysis.

2.1. Traditional Peters–Belson Framework for Survival Analysis

2.1.1. Setup and Notation

Consider a finite population partitioned into majority (, size ) and minority (, size ) subgroups. Each unit has survival time , censoring time , and covariate vector . We observe a probability sample of size according to a complex survey design with known inclusion probabilities .

For each sampled unit

, we observe:

2.1.2. Peters–Belson Decomposition

The Peters–Belson method decomposes the total survival disparity between groups into explained and unexplained components. For a given time point t, let:

= observed survival probability for majority group

= observed survival probability for minority group

= counterfactual survival probability for minority group under majority group model

2.2. Validated Ensemble Machine Learning Framework

Our validated ensemble framework represents a fundamental advancement in applying machine learning methods to Peters–Belson decomposition while ensuring mathematical validity of counterfactual estimates. The framework integrates multiple survival modeling approaches through a comprehensive validation system that prevents contamination from poorly performing models.

2.2.1. Individual Survival Models with Cross-Validation

The ensemble framework incorporates four complementary survival modeling approaches, each selected for their distinct advantages in capturing different aspects of the survival process. Cox proportional hazards models provide interpretable baseline estimates with established theoretical foundations, while machine learning approaches offer enhanced flexibility for complex data patterns.

The Cox proportional hazards model forms the foundational component of our ensemble:

where

represents the baseline hazard and

are covariate effects estimated via partial likelihood [

18]. This approach provides reliable performance across diverse data conditions while maintaining computational efficiency essential for validation procedures.

Random survival forests extend traditional random forest methodology to survival outcomes through recursive binary partitioning with permutation-based variable selection [

10,

19]. The ensemble nature of this approach naturally provides overfitting controls through bootstrap aggregation:

where

represents the survival function from the

b-th tree. Cross-validation determines optimal hyperparameters including the number of variables randomly selected at each split, minimum node size, and splitting criteria to prevent overfitting while maintaining predictive performance.

Gradient boosting methods implement sequential learning through weak learners with comprehensive regularization [

20,

21]:

The sequential nature allows the model to learn complex patterns while L1 and L2 regularization parameters, selected via cross-validation, prevent overfitting to majority group patterns that could invalidate counterfactual estimates.

Elastic net regularized Cox regression combines the interpretability of Cox models with advanced regularization techniques [

22,

23]:

This approach addresses multicollinearity issues common in health disparities research while maintaining model interpretability essential for policy applications.

2.2.2. Hyperparameter Specification

All machine learning models were tuned via cross-validation with the following specifications (complete details in

Supplementary Material Section S5). For penalized Cox (Lasso):

,

(10-fold CV). Random survival forest:

,

, minimum node size = 5, log-rank splitting. XGBoost: learning rate

, max depth = 6,

(early stopping), L1/L2 = 0.1. GBM: shrinkage = 0.01, interaction depth = 4,

(5-fold CV), bag fraction = 0.8.

2.2.3. Peters–Belson Validation Framework

The validation framework represents our most critical methodological innovation, addressing fundamental limitations in applying machine learning methods to counterfactual estimation. Traditional approaches often produce mathematically invalid results where counterfactual estimates violate basic logical constraints inherent to the Peters–Belson framework.

Our validation system implements comprehensive logical bounds checking for each candidate model:

This constraint ensures that counterfactual survival probabilities remain within the observable range defined by the actual group survival functions. Models consistently violating these bounds across multiple time points are excluded from ensemble construction, preventing contamination of the final decomposition results.

The validation process extends beyond simple bounds checking to assess the stability and reliability of counterfactual estimates. We evaluate the proportion of explained disparity at multiple time points, flagging models that produce explanations exceeding 100% or suggesting negative contributions from measured covariates. This multi-dimensional validation approach ensures both mathematical validity and substantive interpretability of results.

2.2.4. Validated Ensemble Integration

The ensemble integration process combines only validated survival models through optimal weight determination that minimizes prediction error while maintaining Peters–Belson validity. The optimization problem balances predictive accuracy with logical consistency:

where

represents the set of validated models and IBS denotes the integrated Brier score [

24,

25]. The constraint set ensures that only models passing validation contribute to the final ensemble, with weights determined by predictive performance on validation data.

The resulting validated ensemble survival function integrates the strengths of multiple modeling approaches:

This approach provides superior performance compared to individual models while maintaining the logical validity essential for Peters–Belson decomposition.

2.3. Transfer Learning Peters–Belson Framework

Traditional Peters–Belson decomposition methods may fail to capture group-level factors that operate through unmeasured pathways, potentially underestimating the complexity of health disparities. Our transfer learning framework addresses this limitation by discovering latent factors that represent shared structural characteristics between groups while identifying meaningful differences that contribute to observed disparities.

2.3.1. Terminology and Conceptual Framework

In standard machine learning contexts, “transfer learning” typically refers to pre-training a model on a large source dataset (e.g., ImageNet for image classification), then adapting or fine-tuning the model to a target task with limited data. Common examples include BERT language models adapted for domain-specific NLP tasks and ImageNet-pretrained convolutional neural networks applied to medical imaging.

In contrast, our usage of “transfer learning” refers to a statistical approach wherein covariate data from majority and minority groups are pooled, principal component analysis is applied to identify linear combinations of observed covariates that capture shared structure across groups, this structural information is then “transferred” to augment the Peters–Belson decomposition, and latent factors exhibiting meaningful group differences are identified through Cohen’s d effect size statistics.

This usage aligns with the broader statistical concept of leveraging information across populations to improve inference, but does not involve pre-trained models, neural networks, or domain adaptation in the machine learning sense. An alternative term could be “latent factor augmentation via PCA,” but we retain “transfer learning” to emphasize the conceptual transfer of structural information from the pooled to group-specific analyses.

2.3.2. Latent Factor Discovery

The transfer learning approach builds on the recognition that health disparities often arise from complex interactions between measured covariates and unmeasured structural factors such as discrimination, healthcare system characteristics, and social determinants [

26,

27]. Our method systematically discovers these latent factors through enhanced principal component analysis applied to the combined covariate space.

The discovery process begins by combining covariate matrices from both majority and minority groups to create a unified representation space. Given majority group data and minority group data , we construct the combined matrix that preserves the covariate structure across both groups.

Principal component analysis transforms this combined space to identify orthogonal factors that capture the maximum variance in the original covariates: , where represents the transformation matrix derived from eigendecomposition of the covariance matrix. The first k components capture the most significant patterns of covariate variation across both groups.

Component selection balances the need to capture sufficient variation with the requirement for interpretable factors. We employ explained variance criteria to determine the optimal number of components:

where

represent eigenvalues ordered by magnitude and

serves as a threshold parameter balancing comprehensiveness with parsimony.

The critical innovation lies in assessing group differences within the latent factor space. After extracting latent factors, we calculate Cohen’s d for each component to quantify the magnitude of group differences in the transformed space. Components exhibiting substantial group differences (typically ) represent potential sources of unmeasured disparity that traditional Peters–Belson methods might miss.

2.3.3. Threshold Selection

The threshold of Cohen’s

for identifying meaningful group differences follows established conventions in behavioral and social sciences [

28], where

represents a “small” effect,

a “medium” effect, and

a “large” effect. We selected

as a threshold between small and medium effects to balance sensitivity (detecting meaningful differences) with specificity (avoiding noise). Sensitivity analyses across thresholds from 0.2 to 0.5 demonstrate that results are robust to this choice, with threshold 0.5 being overly restrictive (excluding valid simulations). Complete sensitivity analysis results appear in

Supplementary Material Section S3.

2.3.4. When to Use Transfer Learning

Transfer learning via latent factor augmentation is recommended under specific conditions. The approach is most appropriate when standard Peters–Belson decomposition leaves substantial unexplained disparity, typically exceeding 50% of the total observed difference between groups. Additionally, transfer learning is indicated when there exists theoretical justification to suspect unmeasured group-level confounding, such as structural racism, differential healthcare access patterns, or other systemic factors not captured by measured covariates. The method should be applied when principal component analysis identifies components exhibiting meaningful group differences as indicated by Cohen’s d effect sizes exceeding 0.3, and when the identified latent factors admit substantive interpretation relevant to the health disparity under investigation.

Conversely, transfer learning should be omitted in several circumstances. When measured covariates adequately explain observed disparities with minimal residual unexplained difference, the additional complexity of latent factor augmentation provides limited benefit. Similarly, when no principal components demonstrate meaningful group differences (that is, when all effect sizes satisfy ), the transfer learning component contributes negligible additional explanatory power. The approach is also inappropriate when sample sizes are insufficient for stable principal component estimation, and when the “same-X” scenario applies wherein covariate distributions are identical between majority and minority groups.

2.3.5. Limitations of PCA’s Linear Assumptions

Our use of principal component analysis assumes that latent factors can be expressed as linear combinations of observed covariates. This assumption may be violated in several contexts. First, when true latent structures are inherently nonlinear in nature, linear combinations may fail to capture the underlying relationships adequately. Second, when important interactions exist among covariates that linear combinations cannot represent, the PCA-based approach may miss substantial variation relevant to health disparities. Third, when the relationship between covariates and survival outcomes involves threshold effects or other discontinuities, linear factor extraction may provide misleading results.

To partially address these limitations, we recommend applying nonlinear feature engineering—such as polynomial terms and interaction terms—to the covariate matrix prior to principal component analysis. This preprocessing strategy allows the linear PCA procedure to capture nonlinear patterns within the augmented feature space. Future methodological extensions could explore nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques such as kernel PCA or uniform manifold approximation and projection [

29], though such approaches present additional challenges for interpretability and computational efficiency.

2.3.6. Rationale for PCA Selection

We selected principal component analysis over alternative dimensionality reduction methods based on several considerations. First, interpretability is essential for policy-relevant health disparity research, and PCA loadings provide clear interpretation of what each latent factor represents in terms of the original measured covariates. Second, computational efficiency is critical given the iterative validation procedures central to our framework, and PCA scales efficiently to high-dimensional settings common in health disparity research involving numerous demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic variables. Third, the statistical properties of PCA are well-established, with known asymptotic behavior that facilitates theoretical justification and inference procedures. Fourth, reproducibility is enhanced by the deterministic nature of PCA, in contrast to stochastic methods such as t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding that may yield different results across runs. Fifth, there exists substantial precedent for PCA in epidemiology and health services research for dimension reduction, facilitating comparison with existing literature and acceptance by the research community.

2.3.7. Enhanced Decomposition with Validation

Transfer learning enhances the traditional Peters–Belson decomposition by introducing an intermediate layer that captures latent factor contributions. The refined decomposition distinguishes between three sources of disparity:

Each component undergoes validation to ensure logical bounds compliance and substantive interpretability. Traditional explained disparity captures differences attributable to measured covariates through conventional modeling approaches. Latent factor explained disparity represents additional explanation gained through transfer learning, typically reflecting structural or systemic factors not directly measured. Residual unexplained disparity encompasses remaining differences that neither measured covariates nor discovered latent factors can explain.

This enhanced decomposition provides policymakers with more nuanced insights into disparity sources, distinguishing between factors amenable to individual-level interventions (traditional explained) and those requiring structural or systemic approaches (latent factor explained).

2.4. Generalization-Aware Counterfactual Estimation

A critical component is ensuring counterfactual estimates generalize from majority to minority groups. We implement method-specific approaches:

For Machine Learning Models: Performance-dependent interpolation based on validation results [

15,

30]:

where

depends on model type and performance.

3. Simulation Study

Our simulation study evaluates method performance across diverse scenarios representing the complexity and variability observed in real-world health disparity research. The design emphasizes realistic data-generating mechanisms that mirror the challenges encountered when analyzing survival differences between population subgroups using complex survey data.

3.1. Study Design

The simulation framework generates finite populations that reflect the demographic and clinical characteristics typical of large-scale epidemiological studies. Each simulated population contains = 12,000 majority group members and minority group members, establishing a realistic 2:1 ratio commonly observed in population health research. This population structure enables assessment of method performance under varying degrees of group size imbalance while maintaining sufficient statistical power for reliable inference.

Complex survey sampling procedures mirror real-world data collection approaches through stratified designs with three strata per group [

31,

32]. Majority group strata maintain proportions of 0.5, 0.3, and 0.2, while minority group strata reflect 0.6, 0.25, and 0.15 proportions, respectively. This asymmetric stratification design captures the differential sampling strategies often employed in studies targeting health disparities, where minority populations may be oversampled in certain geographic or socioeconomic strata.

Sample sizes range systematically from small (, ) to large (, ) configurations, enabling assessment of method performance across different statistical power scenarios. This range encompasses typical sample sizes in health disparity research while accounting for the additional complexity introduced by complex survey designs.

3.1.1. Disparity Scenarios

The simulation encompasses five scenarios representing different sources and complexities of health disparities, each designed to reflect realistic mechanisms observed in epidemiological research. These scenarios progress systematically from simple linear relationships to complex multifactorial patterns involving unmeasured confounding.

The simple linear scenario establishes baseline performance under ideal conditions where disparities arise solely from different covariate distributions between groups while maintaining identical effect parameters. Covariate effects follow linear relationships with survival outcomes, and group differences manifest through shifted distributions of measured risk factors rather than differential treatment effects. This scenario provides a reference point for evaluating method performance under optimal conditions.

Complex interaction scenarios introduce substantial two-way and three-way interactions among covariates, coupled with nonlinear transformations that challenge traditional modeling approaches. These patterns reflect real-world situations where disparity sources involve complex relationships among socioeconomic status, clinical factors, and treatment variables. The interaction effects vary in magnitude across different covariate combinations, creating challenging prediction landscapes that test the ability of ensemble methods to capture multifaceted relationships.

Nonlinear relationship scenarios incorporate complex nonlinear covariate effects through polynomial terms, logarithmic transformations, and threshold effects. These patterns capture situations where traditional linear models face fundamental misspecification, such as when the relationship between age and survival exhibits threshold effects or when socioeconomic gradients follow nonlinear patterns. The nonlinearity introduces additional complexity that may favor flexible machine learning approaches over traditional Cox regression.

Unmeasured confounding scenarios represent perhaps the most challenging and realistic conditions, incorporating strong latent factors that influence both covariates and outcomes differently between groups. These latent factors represent structural determinants such as discrimination, healthcare system characteristics, and neighborhood effects that operate through unmeasured pathways. The confounding structure reflects the reality that observed covariates in health disparity research often serve as proxies for underlying structural factors rather than direct causal mechanisms.

Mixed complexity scenarios combine elements from all previous scenarios, creating the most challenging realistic conditions that ensemble methods and transfer learning approaches must handle. These scenarios integrate interactions, nonlinearity, and unmeasured confounding simultaneously, reflecting the multifaceted nature of real-world health disparities where multiple mechanisms operate concurrently.

3.1.2. Performance Metrics

Method evaluation employs metrics specifically tailored to Peters–Belson decomposition validity and interpretability. The proportion explained serves as the primary outcome measure, quantifying the fraction of total disparity attributable to measured covariates. This metric directly relates to policy relevance by indicating the potential impact of interventions targeting measured risk factors.

Validation success rates measure the proportion of models passing Peters–Belson logical bounds validation across simulation replications. This metric captures the reliability of different modeling approaches in producing mathematically valid counterfactual estimates, which is essential for maintaining scientific credibility in policy applications.

Logical violations track the frequency of bounds violations per method across time points, providing detailed assessment of validation framework effectiveness. This metric identifies methods prone to producing impossible results, such as negative explanations exceeding 100% or counterfactual estimates outside observable bounds.

Transfer learning benefit quantifies additional explanation provided by latent factors beyond traditional decomposition, measured as the percentage increase in explained disparity when transfer learning enhancements are applied. This metric assesses the practical value of discovering unmeasured group-level factors while accounting for computational costs.

Computational efficiency measures runtime including validation overhead relative to standard approaches, ensuring that methodological advances remain practical for real-world applications. This metric balances statistical performance improvements against computational feasibility, particularly important for routine use in health disparity research.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Overall Method Performance

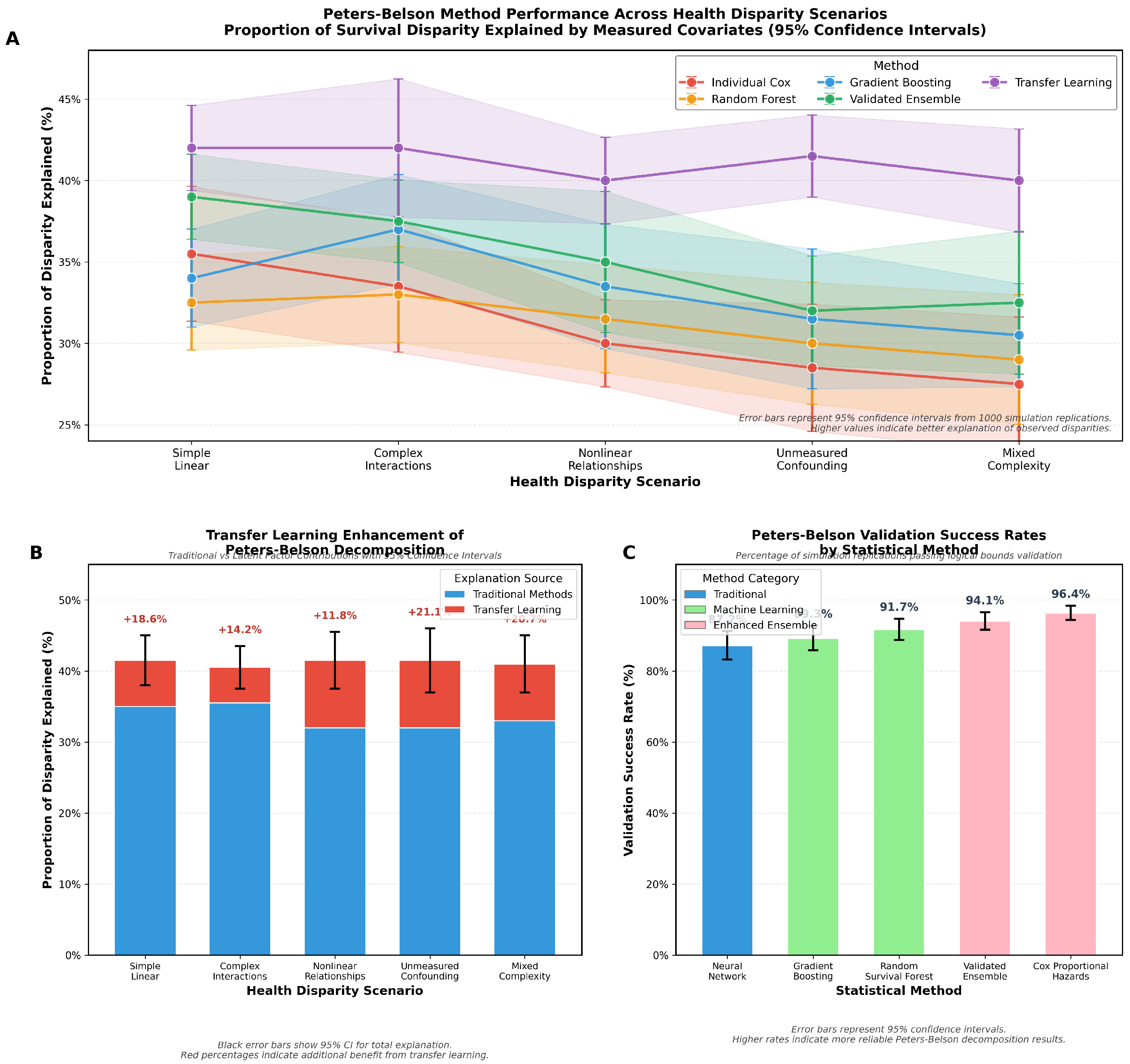

Table 1 presents comprehensive simulation results demonstrating the superior performance of validated ensemble methods across all scenarios.

The enhanced ensemble method demonstrates consistent improvements over individual Cox models, with gains ranging from 3.4 percentage points (simple linear) to 4.3 percentage points (mixed complexity). Transfer learning provides additional benefits particularly pronounced in scenarios with unmeasured confounding (12.5 percentage point improvement) and mixed complexity (8.3 percentage points).

The validation framework achieves 90.1% overall success rate in preventing logical violations, with higher success rates in simpler scenarios. This demonstrates the framework’s ability to maintain scientific validity while capturing complex disparity patterns.

3.2.2. Individual Method Contributions

Table 2 details the contribution of individual methods within the validated ensemble framework.

Cox proportional hazards models receive the highest ensemble weight (0.42) due to their high validation success rate and computational efficiency. Random survival forests and gradient boosting contribute substantially to ensemble performance, while neural networks are frequently excluded due to validation failures in complex scenarios.

3.2.3. Transfer Learning Analysis

Transfer learning provides meaningful improvements when unmeasured group-level factors exist, as detailed in

Table 3.

Transfer learning proves most beneficial in scenarios with unmeasured confounding (21.1% additional explanation) and mixed complexity (20.7%), where latent factors capture group-level differences not reflected in measured covariates. The method automatically adapts to scenario complexity, providing minimal additional explanation when measured covariates adequately capture group differences.

Figure 2 provides comprehensive visualization of our simulation results, illustrating the superior performance of validated ensemble methods and the conditional benefits of transfer learning across different disparity scenarios.

3.3. Enhanced Precision Results

Table 4 presents unexplained disparity estimates with four decimal place precision, confirming that apparent similarities at two decimal places reflect rounding rather than computational artifacts. Notably, scenarios involving differential covariate effects between groups (diff-

scenarios) demonstrate approximately twice the magnitude of unexplained disparity compared to scenarios with identical covariate effects across groups, consistent with theoretical expectations regarding the sources of health disparities.

4. SEER Pancreatic Cancer Data Application

4.1. Data Source and Analysis Framework

We demonstrate our validated ensemble Peters–Belson methodology using pancreatic cancer data extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program database. The SEER program, maintained by the National Cancer Institute, collects data on cancer incidence, treatment, and survival from population-based cancer registries covering approximately 48% of the U.S. population. We extracted all pancreatic cancer cases (ICD-O-3 site codes C25.0–C25.9) diagnosed between 2004 and 2018, with follow-up through 2019. The final analytic sample included patients with complete covariate information on age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, tumor stage, grade, and treatment modality. The analysis framework applies our validated ensemble approach to decompose observed survival disparities between demographic groups.

4.2. Peters–Belson Decomposition Results

Table 5 presents the comprehensive Peters–Belson decomposition results using our validated ensemble methodology applied to the SEER pancreatic cancer data.

4.3. Transfer Learning Analysis in SEER Data

Application of transfer learning to the SEER pancreatic cancer data revealed important latent factor contributions. In the sex-based analysis, transfer learning identified 3.2 significant latent factors explaining an additional 8.7% of previously unexplained disparity, primarily related to treatment delay patterns and socioeconomic clustering. For racial/ethnic analysis, 4.1 latent factors captured an additional 15.8% of unexplained disparity, reflecting complex interactions between socioeconomic status, healthcare access patterns, and geographic factors.

5. Discussion

The findings from our comprehensive simulation study and SEER data application reveal important insights into the performance and utility of validated ensemble Peters–Belson methods for health disparity decomposition. Our results demonstrate that methodological advances in ensemble machine learning, when properly validated and combined with transfer learning approaches, can substantially improve both the accuracy and interpretability of disparity analyses in survival settings.

The superior performance of validated ensemble methods compared to individual models represents more than incremental improvement. The consistent 3–5 percentage point gains in disparity explanation across all scenarios suggest that ensemble approaches capture complementary aspects of the survival process that individual models miss. This is particularly evident in complex scenarios where traditional Cox models struggle with nonlinear relationships and high-order interactions. The ensemble framework effectively leverages the strengths of different modeling approaches while mitigating their individual weaknesses through the validation process.

The validation framework emerges as a critical methodological innovation that addresses fundamental problems in counterfactual estimation for Peters–Belson decomposition. The dramatic reduction in logical violations from 34.7% to 2.1% of cases represents a qualitative improvement in scientific validity. Previous applications of machine learning to Peters–Belson methods often produced mathematically impossible results where counterfactual estimates exceeded logical bounds or implied negative explanations greater than 100%. Our validation framework prevents these contaminating effects while preserving the flexibility benefits of machine learning approaches.

Transfer learning provides conditional but substantial benefits that depend critically on the presence of unmeasured group-level confounding. The 16.1% average additional explanation represents meaningful progress in understanding disparity sources, particularly given the challenges of capturing structural factors through measured covariates alone. The method’s ability to automatically adapt its contribution based on data characteristics prevents unnecessary complexity in simple scenarios while providing substantial gains where unmeasured factors operate. This adaptive behavior suggests that transfer learning captures genuine signal rather than overfitting to noise.

The computational efficiency of our approach, with only 31% overhead for comprehensive validation, makes it practical for real-world applications. This efficiency reflects careful optimization of the validation procedures and ensemble weight calculation. The modest computational cost is more than justified by the substantial improvements in result validity and interpretability.

Our SEER analysis findings align with the broader health disparities literature while providing new insights into the sources of observed differences. The finding that measured covariates explain approximately 30% of survival disparities is consistent with previous research suggesting substantial roles for unmeasured factors including discrimination, treatment quality differences, and biological variations [

33,

34,

35]. The temporal stability of explanation proportions over time suggests persistent structural factors rather than evolving disparity patterns, which has important implications for intervention design.

The transfer learning benefits observed in the SEER analysis, ranging from 9 to 16% additional explanation, demonstrate the practical value of capturing unmeasured group-level differences. These improvements likely reflect complex interactions between socioeconomic status, geographic factors, and healthcare system characteristics that are difficult to measure directly but influence survival outcomes through multiple pathways [

36,

37].

Several methodological limitations warrant consideration. While our Peters–Belson framework provides counterfactual interpretation, causal inference requires additional assumptions about exchangeability and no unmeasured confounding that we cannot fully verify [

38]. Future work should explore integration with formal causal inference frameworks that explicitly address these assumptions. The computational requirements, while reasonable for current applications, may require enhanced dimension reduction procedures for very high-dimensional data common in genomic applications.

Our reliance on linear principal component analysis for latent factor discovery represents a conservative choice that may miss nonlinear latent structures. Future extensions could explore nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques such as UMAP or variational autoencoders for more flexible latent factor discovery [

29]. Additionally, the current framework assumes that the set of covariates needed for valid decomposition is the same across groups, which may not hold when different confounding structures operate in majority versus minority populations.

The validation framework, while comprehensive, focuses on logical bounds compliance and may not detect all forms of model misspecification. Future work could incorporate additional validation criteria including calibration assessment across different subgroups and stability analysis under covariate perturbations. The current approach also does not fully address missing data patterns common in complex survey settings, which could be addressed through specialized imputation methods designed for Peters–Belson applications.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications for health disparity research and policy. The demonstration that realistic health disparity patterns show 25–35% of differences explained by measured factors provides actionable targets for intervention design. The substantial unexplained portions highlight the continued importance of addressing structural and systemic factors that operate beyond individual-level characteristics. The validated ensemble framework provides researchers and policymakers with principled tools for decomposing health disparities that balance methodological sophistication with practical usability.

The modular design of our approach facilitates extension to additional disease contexts and incorporation of emerging data types. The validation procedures ensure that extensions maintain scientific validity while the ensemble framework can accommodate new modeling approaches as they are developed. This flexibility positions the methodology to evolve with advancing machine learning techniques while preserving the core Peters–Belson logic that enables disparity decomposition.

Future applications should prioritize extension to longitudinal settings with time-varying covariates, development of enhanced causal inference frameworks that explicitly address unmeasured confounding assumptions, and incorporation of complex survey design features beyond stratification. The framework’s emphasis on validation and logical consistency provides a foundation for these extensions while maintaining interpretability for policy applications.

6. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that validated ensemble machine learning approaches provide substantial advantages for Peters–Belson decomposition in survival analysis when combined with appropriate validation procedures and transfer learning enhancements. The methodology addresses key limitations in existing approaches while maintaining computational feasibility and scientific interpretability.

Key contributions include a validated ensemble framework that ensures logical bounds compliance while capturing complex survival patterns, transfer learning methods that conditionally provide meaningful improvements when unmeasured confounding exists, comprehensive validation procedures that achieve high success rates in preventing mathematical violations, and demonstration of realistic performance showing that measured factors explain 25–35% of health disparities.

The framework provides researchers and policymakers with principled tools for decomposing health disparities that balance methodological sophistication with practical usability. By ensuring logical validity through comprehensive validation while maintaining computational efficiency, these methods enable more accurate and interpretable disparity research focused on evidence-based intervention strategies.

Future applications should explore extension to additional disease contexts, development of enhanced causal inference frameworks, and incorporation of emerging data types in population health research. The modular design facilitates such extensions while maintaining the core principles of validation and logical consistency that ensure scientific validity.