1. Introduction

As in other countries, Japan has experienced a growing interest in the issue of abuse in relation to COVID-19 [

1,

2]. The number of child abuse cases where child guidance centers (CGCs) are notified has been increasing in Japan every year: in fiscal year (FY) 2020 (April 2020 to March 2021), the number of notifications of and consultations with CGCs was 205,044 [

3], which was approximately double the number in FY2015, 3.6 times the number in FY2010, and 11.6 times the number in FY2000 [

3]. Psychological abuse is the most prominent form of child abuse, with 121,334 cases in FY2020, which is 8.1 times the number in FY2010 [

3]. It is believed that the rapid increase in child abuse has been influenced by the social recognition of child abuse, notifications of CGCs, and establishment of a system in 2013 that mandated active intervention by the police in cases of domestic violence [

4].

In FY2020, 3427 (1.7% of the total) child abuse cases were detected at medical institutions and reported to the CGC or the welfare office (WO) [

3]. This figure is quite small compared to other settings but is 1.6 times the number of cases in FY2010 [

3]. Thus, medical institutions, especially those that provide pediatric care and emergency medicine services, are required to deal with cases of suspected child abuse. The “Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (Act No. 82 of 24 May 2000)” [

5] enacted in 2000 mandates that medical personnel make efforts toward the early detection of child abuse, since they occupy a front-line position wherein child abuse is detected.

Teachers, officials and other staff workers of schools, child welfare institutions, hospitals, prefectural police, public women’s counseling centers, education committees, spousal violence counseling and support centers and other bodies involved in child welfare in the course of their operations, and officials of child welfare institutions, medical practitioners, dental practitioners, public health nurses, midwives, clinical nurses, attorneys-at-law, police, women’s consultants, and other persons involved in child welfare in the course of their duties, must endeavor to detect child abuse at an early stage, acknowledging that they are in a position to easily detect child abuse.

In addition, it is essential to report cases of suspected child abuse to the CGC/WO.

A person who has detected a child who appears to have suffered child abuse must promptly give notification to the municipality or the welfare office or child guidance center established by the prefecture, or to the municipality or such welfare office or child guidance center through a commissioned child welfare volunteer.

Furthermore, medical institutions can contact the police in cases where injury or other physical markers of abuse are suspected. Consequently, medical institutions play a major role in responding to child abuse, and the behavior/awareness of physicians—who are required to handle such cases at the front line—is significant. Medical institutions often face difficulties in dealing with cases of child abuse, such as identifying the criteria for notifying the CGC/WO and establishing a medical relationship with parents/guardians who are perpetrators of child abuse.

In order to obtain basic data to formulate appropriate countermeasures and support requirements for medical institutions, in this study, we conducted a self-administered, anonymous questionnaire survey among pediatrics departments’ staff (PED), emergency medicine departments’ staff (ED), and general affairs departments’ staff (GA) of large hospitals in Japan. This survey determined the awareness and actual behavior of health care providers regarding the reporting of child abuse to the CGC/WO and police.

The obligation of medical personnel or medical institutions to notify or to report suspected child abuse to the government is difficult to grasp on a global scale. In the United States, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act was enacted in 1974, which established provisions regarding the obligation to notify [

6,

7]. The legal procedures vary from state to state, but in California, for example, the state law stipulates that teachers, medical personnel, and employees of public institutions are obligated to notify, and the obligation is placed on the individual [

8]. According to a survey conducted between 2012 and 2013 in 22 European countries, physicians were obligated to notify suspected child abuse in 16 of the 22 countries [

9]. Although physicians nationally in Belgium, Germany, Malta, the Netherlands, Ireland, and the UK are not obliged to notify, the response in some cases differs at the state level [

9], making a uniform understanding difficult. There have been several previous studies on the gap between compliance with notification obligations and actual notifications made by health care providers and institutions [

10,

11,

12]. Among others, a survey of 2485 German healthcare professionals found that 20% of study participants did not choose to notify the child protection system (CPS) even if they were certain that child maltreatment had occurred [

12]. This indicated that distress regarding the obligation to notify and report child abuse among healthcare professionals can be a problem in many countries. Note that in Japan, even if a physician who suspects abuse fails to notify the CGC/WO of it, the physician in question is generally not legally penalized. Although this paper analyzed the behavior of physicians under the Japanese legal system, the data presented here may be useful for other countries that have introduced similar systems, as well as for other efforts in other countries.

2. Methods

2.1. Participating Institutions

The following institutions and their departments were surveyed for this study.

(1) PED/ED/GAs of core clinical training (FY2017) and university hospitals (1034 hospitals).

(2) PED/ED/GAs of hospitals established by the Japan Medical Association (77 hospitals).

2.2. Questionnaire Survey Method

The self-administered and anonymous questionnaire survey was distributed via mail. The survey instructions and questionnaire were mailed to the institutions listed above. The questionnaire was distributed on 1 April 2018, and the deadline for response submission was 13 April 2018. However, responses received after the deadline were also included in the analysis. We stopped collecting the responses after 30 April 2018.

We carefully examined previous child abuse cases reported in the media and related court cases to prepare the questionnaire. In addition, medical personnel (physicians, nurses, and administrative staff) were interviewed regarding the current situation of child abuse and institutional handling of child abuse. Subsequently, a questionnaire (pilot version) was developed and pretested among medical personnel (pediatricians and emergency department physicians). The final survey questionnaire (summarized in

Table 1) was developed based on the results of the pilot survey.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

After calculating descriptive statistics for each item for all participating institutions, the three groups (PED, ED, GA) and the two groups (when notifying CGC/WO, when reporting to police) were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis tests and the Cochran Q tests.

The significance level was set at less than 5% on both sides. IBM SPSS version 27 statistical software (IBM Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Participation was voluntary and the questionnaire survey included a document explaining the study’s contents and other information. Since only those who were willing to cooperate with the research were asked to respond, the participant’s informed consent was indicated through their response to the questionnaire.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board at Keio University Graduate School of Health Management (No. 2018–00).

3. Results

3.1. Response Rate and Response Categories

Questionnaires were distributed to 1111 institutions’ PEDs, EDs, and GAs. Of these, 268 were returned from the PEDs, 183 from the EDs, and 166 from the GAs, with response rates of 24.1%, 16.5%, and 14.9%, respectively.

Each medical institution handled child abuse differently, wherein each department handled child abuse independently, either through the joint association between the PED and ED or through the joint association between the GA and medical department. The results of the responses were scrutinized and tabulated by classifying them into the following three categories:

3.2. Number of Cases Considered for Notification/Reporting and Number of Cases Actually Notified/Reported

3.2.1. Number of Cases Considered for Notification/Reporting

The number of cases considered for notification/reporting and the number of cases actually notified/reported in 2017 indicated that about half of the institutes/departments reported zero or a few cases per year, although some institutes/departments handled several hundred cases or more per year.

Table 2 presents the range (minimum to maximum) and median of the number of cases considered for notification/reporting: 0–41 (median = 1) for the PED, 1–21 (median = 0) for the ED, and 0–472 (median = 3) for the GA. The number of GA cases was statistically significantly higher than that of PED and ED cases. The number of PED cases was statistically significantly higher than that of ED cases.

(1) 180 institutions handled cases through the PED alone;

(2) 86 institutions handled cases through the ED alone;

(3) 143 institutions handled cases through the GA (alone or the joint association between the GA and the medical department).

3.2.2. Number of Cases Actually Notified/Reported

The following values depict the range (minimum to maximum) and median of the number of cases actually notified/reported: 0–30 (median = 2) for the PED, 0–7 (median = 1) for the ED, and 0–43 (median = 3) for the GA. The number of GA cases was statistically significantly higher than that of ED cases.

Each institute and department was asked to provide details of the cases that were actually notified/reported.

Table 3 presents these results. The victims were classified under the following age groups: 14.0% newborns, 29.3% infants, 20.6% preschool children, 20.4% elementary school children, 10.3% junior high school children, and 5.3% between 15 and 18 years of age. As for the type of abuse suspected, physical abuse accounted for about half of the cases (48.1%), followed by neglect (33.1%). Abusive head trauma was the most common “other” description under the physical abuse category. Neglect items under the “Other” description varied widely, including “not allowing the child to go to school” and “inadequate nurturing environment.” As for the parents’ situation, 47.5% of the participants selected “no particular abnormality,” which accounted for about half of the responses. “Other” in the “parental situation” section included “young age,” “mental illness (including suspected mental illness),” “alcohol addiction/consumption,” “economic deprivation,” and a wide range of other factors. Slightly less than 84.0% of the cases were reported to the CGC.

3.3. Notifying CGC/WO and Reporting to the Police

3.3.1. Notifying CGC/WO

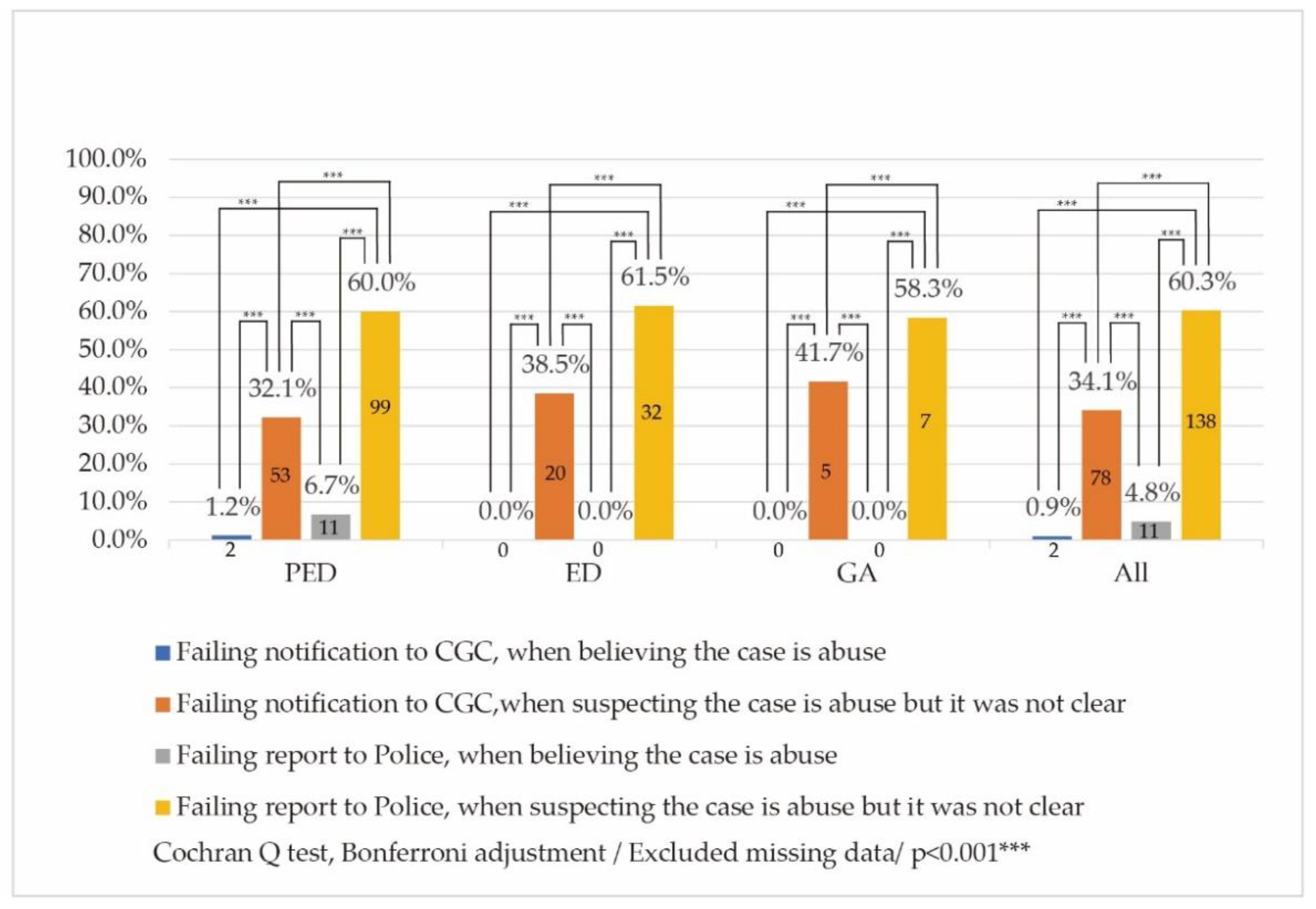

Institutions/departments that acknowledged the presence of cases of possible abuse in the past five years (FY2013–2017) were asked whether they ever failed to notify the CGC/WO or report the incident to the police in cases where they “believed abuse was inflicted” or they “suspected abuse, but were not sure.”

Figure 1 depicts the results. Of the total, two PEDs failed to report cases where they “believed abuse was inflicted” to the CGC/WO. In addition, 53 PEDs, 20 EDs, and 5 GAs did not report cases where they “suspected abuse, but were not sure” to the CGC/WO.

3.3.2. Reporting to the Police

Furthermore, 11 PEDs did not report cases where they “believed abuse was inflicted” to the police. In addition, 99 PEDs, 32 EDs, and 7 (43.6%) GAs failed to report cases where they “suspected abuse, but were not sure” to the police.

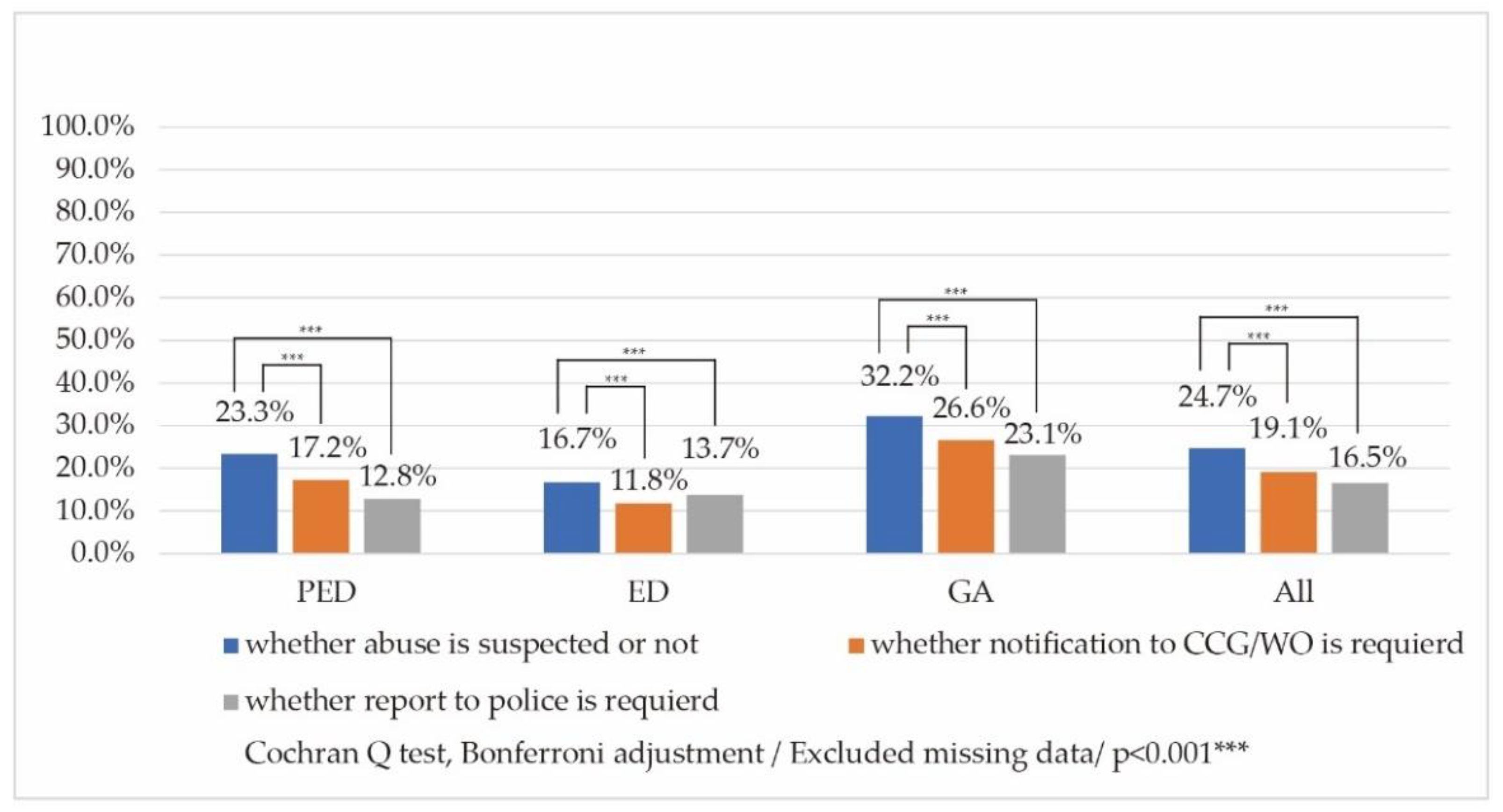

3.4. Disagreements among Staff Regarding the Handling of Abuse

Respondents were asked whether there were any disagreements among their institution’s staff in the past five years (FY2013–2017) in the context of the following: determining “whether abuse is suspected”, “whether notification to the CGC/WO is required”, or “whether reporting to the police is required”.

As shown in

Figure 2, 42 (23.3%) PEDs, 17 (16.7%) EDs, and 46 (32.2%) GAs indicated that sometimes disagreements occurred as to “whether abuse is suspected”. Furthermore, 31 (17.2%) PEDs, 12 (11.8%) EDs, and 38 (26.6%) GAs indicated that disagreements occasionally occurred as to “whether notification of the CGC/WO is required”. Additionally, 23 (12.8%) PEDs, 14 (13.7%) EDs, and 33 (23.1%) GAs reported that sometimes disagreements occurred on “whether reporting to the police is required”.

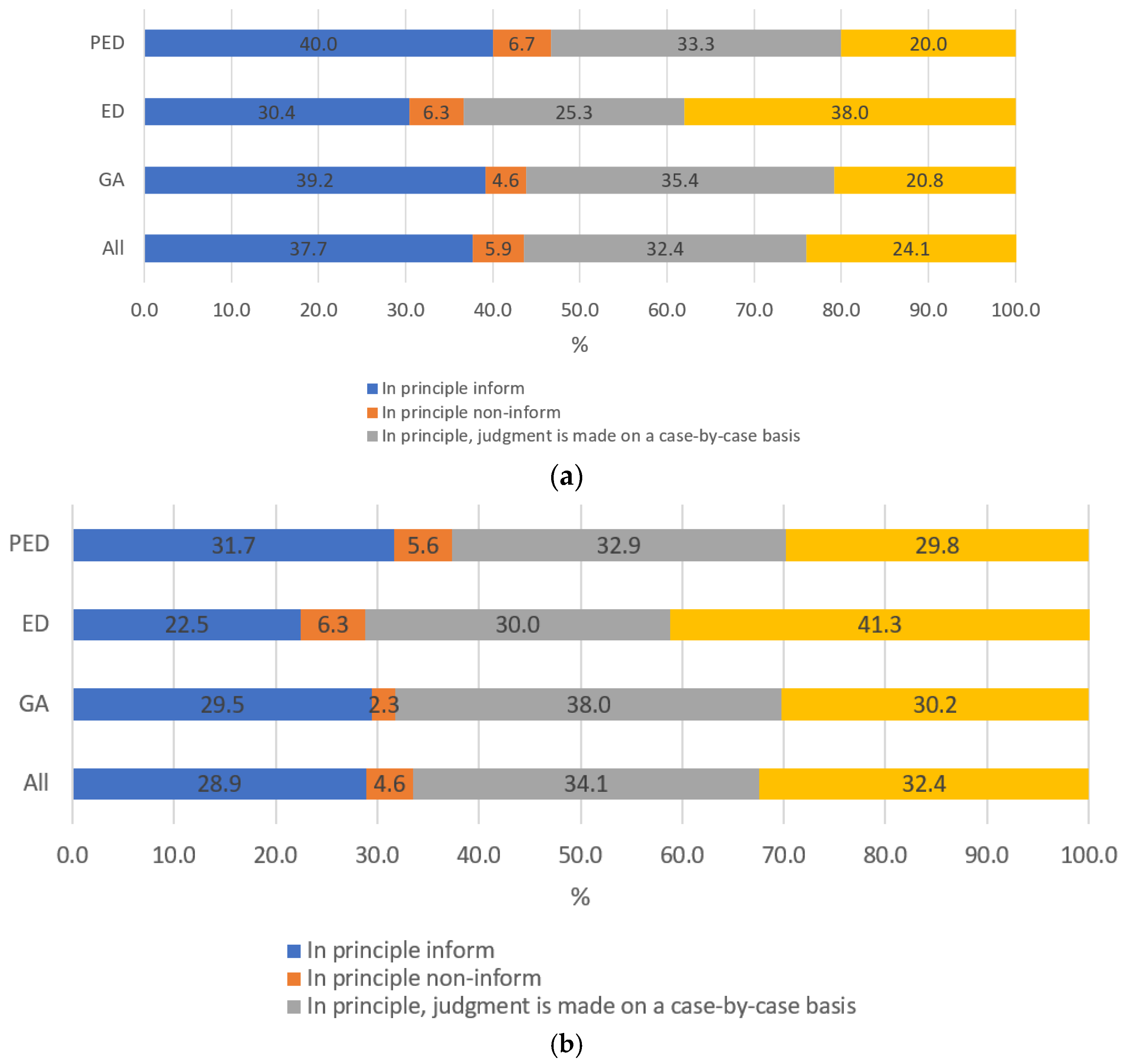

3.5. Informing Parents/Guardians

Respondents were asked whether they informed parents about notifying the CGC/WO or reporting the case to the police upon suspicion of abuse.

As shown in

Table 4, 66 (40.0%) PEDs, 24 (30.4%) EDs, and 51 (39.2%) GAs chose the option of “in principle inform” when notifying the CGC/WO. Furthermore, 11 (6.7%) PEDs, 5 (6.3%) EDs, and 6 (4.6%) GAs chose “in principle non-inform.”

Regarding reporting to the police, 51 (31.7%) PEDs, 18 (22.5%) EDs, and 38 (39.5%) GAs chose “in principle inform.” Furthermore, 9 (5.6%) PEDs, 5 (6.3%) EDs, and 3 (2.3%) GAs chose “in principle non-inform.”

A comparison of the four categories, that is, “in principle inform,” “in principle non-inform,” “in principle, judgment is made on a case-by-case basis,” and “no particular fixed principle,” revealed that institutions tended to “in principle inform” when notifying the CGC/WO more often than when reporting to the police (

Figure 3). No responses were excluded from this analysis. The percentage of “in principle inform” the CGC/WO was statistically significantly higher than the percentage of “in principle inform” the police.

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a self-administered, anonymous questionnaire survey of the PEDs, EDs, and GAs of large hospitals (university hospitals and Japan Medical Association hospitals) in Japan, with the aim of comprehensively surveying the current status of efforts by medical institutions in Japan to investigate cases of suspected child abuse among children visiting medical institutions. In particular, we intended to clarify the actual situation in each medical institution, awareness of the PED/ED/GA, and institutional policies regarding notification of the CGC/WO and reporting to the police.

4.1. About the Medical Institutions Surveyed

The number of medical institutions advocating “pediatrics care” in Japan has decreased over the years. As of 2020, there were 2523 hospitals and 18,798 clinics advocating pediatrics care in Japan. The PEDs covered by this study represented a portion of the total number, which comprised a relatively large scale of PEDs. On the other hand, there were 812 facilities advocating emergency medicine in Japan (as of 2020) [

13]. The survey adequately represented emergency departments since most of the core clinical training hospitals and university hospitals included in this survey fell under the category of Emergency Department Specialist Institutions.

We inferred from this situation that the institutions responding to this survey were likely to be relatively large medical institutions that were concerned about the issue of child abuse and had adequate human resources to address it. It cannot be denied that the ratio of notifications to the CGC/WO and reporting to the police among medical institutions in Japan as a whole may be even lower than in this study.

4.2. Number of Cases Considered for Notification/Reporting and Number of Cases Actually Notified/Reported

Both the number of cases considered for notification/reporting and the number of cases actually notified/reported indicated that about half of the institutions/departments dealt with zero to several cases per year, while the others dealt with several hundred cases or more per year. The discrepancy between the number of cases reviewed and the number of cases actually notified/reported may be due to substantive differences between the two, and issues related to the definition and understanding of the word “review.” Comparing the number of cases handled by a single medical institution and the number of cases handled by the GA (alone or the joint association between the GA and medical department), the latter tended to be higher in terms of cases reviewed and actually notified of/reported. However, the nature of this remained unclear. On the one hand, it is possible that institutions with multiple departments, including a GA, examined child abuse cases from a broader perspective that facilitated the detection of more child abuse cases without omission. On the other hand, it is possible that the absolute number of child abuse cases was high, along with a system of multiple departments, including the GA, to handle the large number of cases.

4.3. Notifying the CGC/WO

The results indicated that two PEDs failed to report certain cases to the CGC/WO, even those where they “believed abuse was inflicted.” Furthermore, 78 institutions/departments failed to report cases to the CGC/WO where they “suspected abuse, but were not sure.” This research could not uncover the reasons behind the failure to report the cases; therefore, further research is required to clarify the same. As noted above, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act imposes an obligation on those who discover child abuse to notify the CGC/WO (Article 6 (1)) [

5].

In addition, compared to when the staff “believed abuse was inflicted,” cases where they “suspected abuse, but were not sure” were less likely to be reported to the CGC/WO and the police. This indicated that in the Japanese system, notifying and reporting cases of child abuse to the CGC/WO and the police, respectively, by medical institutions may have a punitive dimension. In other words, it may indicate that the cases are reported to the CGC/WO and police owing to administrative and criminal interventions and punishments rather than an intention to investigate the case and prevent child abuse. Therefore, medical institutions are cautious about reporting cases of suspected abuse to the CGC/WO and the police.

However, caution was needed in composing the questionnaire regarding “failing to notify and report cases of child abuse to the CGC/WO and the police” because medical institutions may be hesitant to respond openly to this. In other words, it may be tantamount to an admission by the medical institution itself of doing something that does not conform to the intent of Japanese law. If this were the case, the actual rate of failing to notify and report cases of child abuse to the CGC/WO and the police would be much higher. It is also possible that this contributed to the low response rate in this study.

Previous studies included reports from Germany, Sweden, and Australia, which can be compared with the results of this study. Berthold et al. (2021) reported a survey of 2485 physicians and psychotherapists treating children and adolescents in Germany regarding suspicion of child abuse and notification to the CPS [

12]. The probability of reporting to the CPS increased positively with the degree of suspected abuse. However, even when participants had a high degree of certainty that child abuse had occurred, approximately 20% did not choose to notify the CPS. When that certainty was medium, approximately 35% did not choose to report to the CPS [

12]. Talsma et al. (2015) surveyed general practitioners in Sweden regarding notification of child abuse cases to the CPS. In this survey, as well, about 20% of general practitioners did not notify the CPS despite suspicions of child abuse and despite being legally obliged to notify [

11]. The main reasons for non-reporting were suspicion and uncertainty regarding the use of alternative strategies [

11]. The same trend was confirmed in a survey conducted in Australia, where Schweitzer et al. (2006) found that about 25% of medical practitioners failed to report suspected cases of child abuse, even though they were aware of the notification requirement [

14]. Comparing these with our findings, our survey in Japan also showed that medical practitioners’ failure to notify the CGC/WO and report to the police was largely due to uncertainty about suspected abuse. The results were similar to those of the European and Australian studies. However, in Japan, there may be a tendency for more notifications and reporting when certainty is sufficiently high, and a tendency for fewer notifications and reporting when certainty is reduced to a medium level. This suggested that in Japanese culture there is more hesitancy about making responsible decisions in the face of uncertainty.

4.4. Disagreements among Staff Regarding the Handling of Abuse

In particular, the percentage of respondents who indicated that there were disagreements among staff members was high for decisions regarding “whether abuse is suspected or not.” This indicated the difference of opinion among staff members in collaborative decision making involving multiple professions. This was also supported by the fact that the same tendency was observed for “whether notification to the CGC/WO is required” and “whether a police report is required.” However, 23.3% of respondents cited disagreement among staff members on “whether abuse is suspected,” even in the case of PED institutions; this made interpreting the data difficult because it suggested that even experts have difficulty in judging cases of suspected child abuse.

Although it was difficult to clearly isolate the background to such disagreements among staff members, it can be concluded that the presence of disagreements among staff members is probably not detrimental from the perspective of detecting child abuse and preventing further child abuse. Ideally, any suspicion of child abuse should be appropriately shared with the CGC/WO and considered by the broader community.

4.5. Informing Parents/Guardians

It is believed that the psychological burden on medical personnel can be reduced by prescribing a consistent response to whether parents/guardians (who are often the perpetrators of child abuse) should be informed in advance regarding the notification of the case to the CGC/WO and the police. Conversely, it would be unreasonable to prescribe a fixed response, since child abuse cases are complicated and intertwined with a variety of circumstances. The results of this survey reflected this dilemma, with a ratio of approximately 4:6 reflecting institutions that have a general rule for informing patients/guardians about notification of child abuse to the CGC/WO and those that do not, and a ratio of approximately 3:7 for reporting to the police or not. Fewer institutions have a policy of “in principle informing parents/guardians” regarding cases being reported to the police, possibly owing to concerns about the suspects escaping the situation.

Urade et al. (2022) conducted a survey of 323 pediatric institutions in Japan during 2012–2013 (62.4% response rate) to clarify the basic policy of medical institutions regarding whether or not to inform parents about the notification of child abuse cases to the CGC/WO [

15]. The results indicated that 59.6% of the respondents reported that they would inform the parents of child abuse cases. According to the results, 59.8% of the institutions had a policy of notifying the family, 33.7% said the decision varies from case to case, and 6.6% did not have a policy of notifying the family [

15]. The results of this survey were generally consistent with the results of this paper.

4.6. Significance and Limitations

This survey has scientific and social significance because it serves as an explanatory survey that identified factors inhibiting abuse notification and provided basic data for discussions on the nature of the corresponding physician support system.

If the non-respondents had participated in the study, the results might have been different. Nevertheless, the study produced important findings about the concerned field. For example, it was revealed that a small number of medical institutions have experienced cases of child abuse. In addition, some medical institutions were unable to make decisions about notifying the CGC/WO or reporting the case to the police. These findings provided an important basis for formulating necessary measures required in cases of child abuse (e.g., the development of a pamphlet for medical institutions on response policies).

Comprehensive research on notification or report of child abuse is still lacking worldwide. Through comparison with the few previous studies, we can say that, as with German and Swedish health care professionals [

11,

12], Japanese health care professionals demonstrated a gap between their duty to notify and their actual notification behavior, a gap that may lead to an ethical concern. The existence of such a gap in mandatory notification may be a global problem, and we believe that a nationwide survey on notification of child abuse in medical institutions, such as the one we conducted, may be required in other countries.

4.7. Further Research

As COVID-19-related child abuse [

1,

2] has become a social problem in Japan, it is possible that the response to child abuse by medical institutions may also change. Our study was conducted in 2018, so we were not able to consider the impact of COVID-19. Therefore, further study might need to be conducted during or after lockdown periods in Japan in the future. Comparison with this study should clarify the actual situation of child abuse during/after COVID-19, which is likely to become a problem in the future, and provide an opportunity to consider how to deal with the situation accordingly. Although it is difficult to make simple comparisons between Japan and other countries because the systems for notifying and informing about child abuse differ, it would be useful to investigate the situation of notifying and informing about child abuse in countries overseas, similarly to the scheme of this survey, to assess the universality of the study.