Spatial Patterns of Mercury and Geochemical Baseline Values in Arctic Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Sites

2.3. Methods

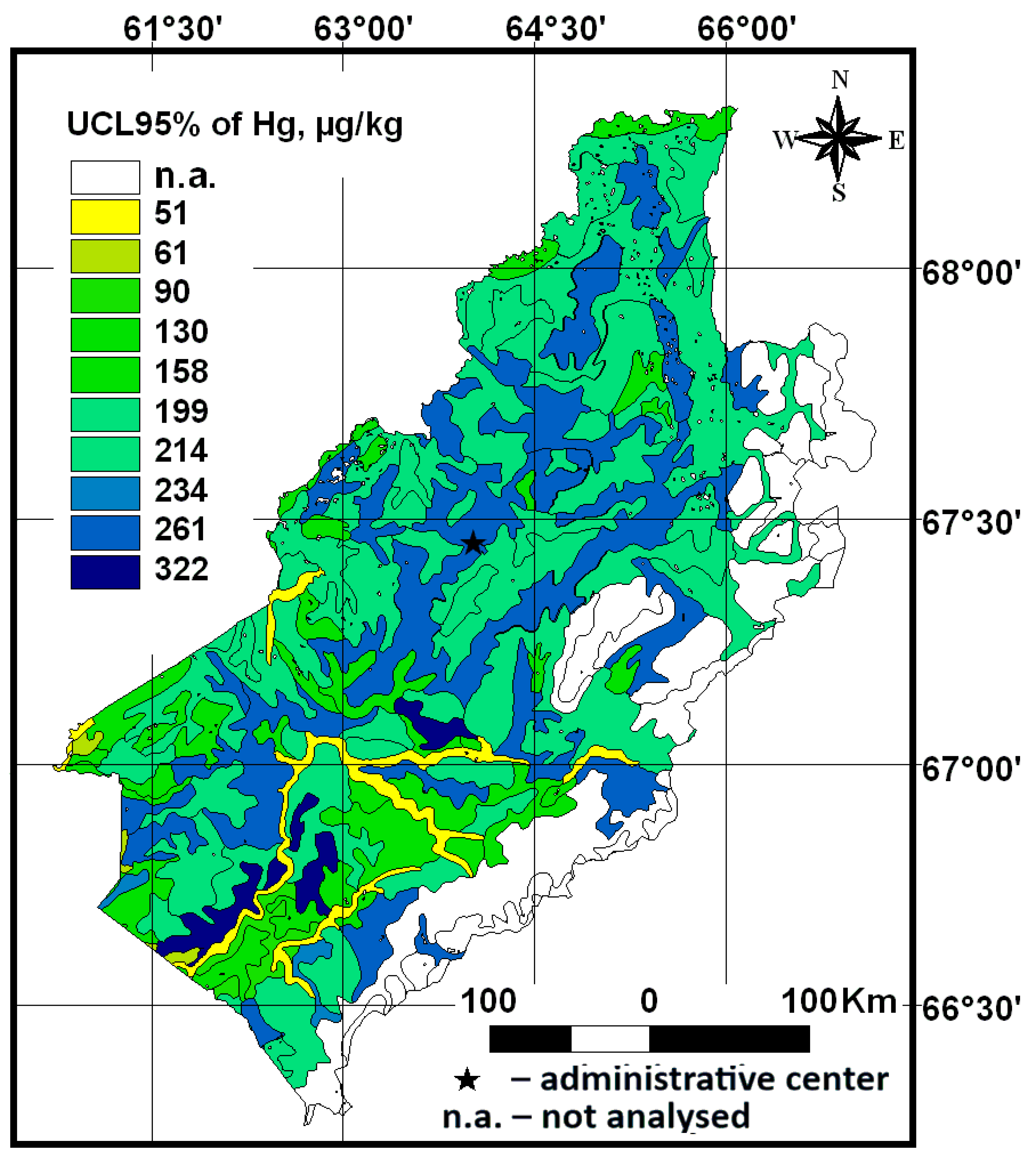

3. Results

3.1. The Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Soils

3.2. The Total Hg Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lodygin, E.D. Content of acid-soluble copper and zinc in background soils of Komi Republic. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2018, 51, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Quynh, N.; Jeong, H.; Elwaleed, A.; Nugraha, W.C.; Arizono, K.; Agusa, T.; Ishibashi, Y. Spatial and seasonal patterns of mercury accumulation in paddy soil around Nam Son Landfill, Hanoi, Vietnam. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beznosikov, V.A.; Lodygin, E.D. Ecological-geochemical assessment of hydrocarbons in soils of northeastern european Russia. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2010, 43, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshunova, V.A.; Lodygin, E.D.; Charykova, M.V.; Chukov, S.N. Sorption interaction of gold and its pathfinder elements with humic acids of peat-podzolic soils. Theor. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 3, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Vashishth, R. From water to plate: Reviewing the bioaccumulation of heavy metals in fish and unraveling human health risks in the food chain. Emerg. Contam. 2024, 10, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Anderson, C.W.N.; Xing, Y.; Shang, L. Remediation of mercury contaminated sites—A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 221–222, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, C.T.; Mason, R.P.; Chan, H.M.; Jacob, D.J.; Pirrone, N. Mercury as a global pollutant: Sources, pathways, and effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4967–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, W.F.; Lamborg, C.H.; Hammerschmidt, C.R. Marine biogeochemical cycling of mercury. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 641–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selin, N.E. The Biogeochemical cycling of mercury in the ocean: A critical review. Ann. Rev. Environ. Res. 2009, 34, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilevich, R.S.; Beznosikov, V.A.; Lodygin, E.D.; Kondratenok, B.M. Complexation of mercury (II) ions with humic acids in tundra soils. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2014, 47, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecina, V.; Valtera, M.; Travnickova, G.; Komendova, R.; Novotny, R.; Brtnicky, M.; Juricka, D. Vertical distribution of mercury in forest soils and its transfer to edible mushrooms in relation to tree species. Forests 2021, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beznosikov, V.A.; Lodygin, E.D.; Nizovtcev, A.N. Spatial and profile distribution of mercury in soils of natural landscapes. Biol. Commun. 2013, 1, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio, C.; Jiskra, M.; Osterwalder, S.; Borrelli, P.; Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. A spatial assessment of mercury content in the European Union topsoil. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvat, P.; Klimes, L.; Pospisil, J.; Klemes, J.J.; Varbanov, P.S. An overview of mercury emissions in the energy industry—A step to mercury footprint assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Jiskra, M.; Borrelli, P.; Liakos, L.; Ballabio, C. Mercury in European topsoils: Anthropogenic sources, stocks and fluxes. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gworek, B.; Dmuchowski, W.; Baczewska-Dabrowska, A.H. Mercury in the terrestrial environment: A review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhou, W.; Su, Y.; Tang, C.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Rupakheti, D.; Kang, S. Spatial distribution and risk assessment of mercury in soils over the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment. Global Mercury Assessment 2018; UN Environment Programme, Chemicals and Health Branch: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/global-mercury-assessment-2018 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Ander, E.L.; Johnson, C.C.; Cave, M.R.; Palumbo-Roe, B.; Nathanail, C.P.; Lark, R.M. Methodology for the determination of normal background concentrations of contaminants in English soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 454–455, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałuszka, A.; Migaszewski, Z.M. Geochemical background an environmental perspective. Mineralogia 2011, 42, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Francés, F.; Martinez-Grana, A.A.; Alonso-Rojo, P.; Garcia-Sanchez, A. Geochemical background and baseline values determination and spatial distribution of heavy metal pollution in soils of the Andes mountain range (Cajamarca Huancavelica, Peru). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, H.G.; Clarke, B.O.; Dasika, R.; Wallis, C.J.; Reichman, S.M. Assessment of ambient background concentrations of elements in soil using combined survey and open-source data. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 580, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloni, F.; Nisi, B.; Gozzi, C.; Rimondi, V.; Cabassi, J.; Montegrossi, G.; Rappuoli, D.; Vaselli, O. Background and geochemical baseline values of chalcophile and siderophile elements in soils around the former mining area of Abbadia San Salvatore (Mt. Amiata, southern Tuscany, Italy). J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 255, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrica, D.; Medico, F.L.; Zuccolini, M.V.; Miola, M.; Alaimo, M.G. Geochemical baseline values determination and spatial distribution of trace elements in topsoils: An application in Sicily region (Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, F.; Gozzi, C.; Cabassi, J.; Nisi, B.; Rappuoli, D.; Vaselli, O. Integrating Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) and Random Forest for lithology-specific geochemical baseline determination. Sci. Total Environ. 2026, 1011, 181169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovolsky, G.V.; Taskaev, A.I.; Zaboeva, I.V. (Eds.) Soil Atlas of the Komi Republic; LC Komi Republic Publishing House: Syktyvkar, Russia, 2010; p. 356. [Google Scholar]

- Kaverin, D.A.; Pastukhov, A.V.; Marushchak, M.; Biasi, C.; Novakovsky, A.B. Effects of microclimatic and landscape changes on the temperature regime and thaw depth under a field experiment in the Bolshezemelskaya tundra. Earth’s Cryosphere 2020, 24, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaverin, D.A.; Pastukhov, A.V.; Lapteva, E.M.; Biasi, C.; Marushchak, M.; Martikainen, P. Morphology and properties of the soils of permafrost peatlands in the southeast of the Bol’shezemel’skaya tundra. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2016, 49, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaverin, D.; Pastukhov, A.; Novakovskiy, A.; Malkova, G.; Sadurtdinov, M.; Skvortsov, A.; Tsarev, A.; Zamolodchikov, D.; Shiklomanov, N.; Pochikalov, A.; et al. Long-term active layer monitoring at CALM sites in the Russian European North. Polar Geogr. 2021, 44, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodygin, E.; Alekseev, I.; Nesterov, B. Landscape–geochemical assessment of content of potentially toxic trace elements in Arctic soils. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamrikova, E.V.; Vanchikova, E.V.; Lu-Lyan-Min, E.I.; Kubik, O.S.; Zhangurov, E.V. Which method to choose for measurement of oranic and inorganic carbon content in carbonate-rich soils? Advantages and disadvantages of dry and wet chemistry. Catena 2023, 228, 107151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanchikova, E.V.; Lapteva, E.M.; Vasilyeva, N.A.; Kondratenok, B.M.; Shamrikova, E.V. Metrological aspects of studying the particle size distributionof soils according to the Kachinskii method. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2024, 57, 1176–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MI No. 88-17641-004-2018; Measurement Methodology. Soils, Grounds, Bottom Sediments and Peat. Methodology for Measuring the pH Value, the Specific Electrical Conductivity of Aqueous Extracts and the Mass Fraction of Solid Residue in the Test Materials. State Committee of Russia for Environmental Protection: Moscow, Russia, 2018; p. 27. (In Russian)

- PND F 16.1:2.23-2000; Quantitative Chemical Analysis of Soils. Methodology For Measuring the Mass Fraction of Total Mercury in Soil and Ground Samples Using an RA-915+ Mercury Analyser With an RP-91C Attachment. State Committee of Russia for Environmental Protection: Moscow, Russia, 2005; p. 13. (In Russian)

- EPA. Calculating Upper Confidence Limits for Exposure Point Concentrations at Hazardous Waste Sites; Publication OSWER 9285.6-10; Office of Emergency and Remedial Response U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; p. 32.

- State Soil Map of the Russian Federation. Sheet Q-41 (Vorkuta) at Scale of 1:1,000,000; Federal Geodesy and Cartography Service of Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2000. (In Russian)

- Grigal, D.F. Mercury sequestration in forests and peatlands: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 2003, 32, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyllberg, U. Competition among thiols and inorganic sulfides and polysulfides for Hg and MeHg in wetland soils and sediments under suboxic conditions: Illumination of controversies and implications for MeHg net production. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2008, 113, G00C03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyllberg, U. Chemical speciation of mercury in soil and sediment environmental chemistry and toxicology of mercury. Environmental Chemistry and Toxicology of Mercury; Liu, G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 219–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, C.L.; Bockheim, J.G.; Kimble, J.M.; Michaelson, G.J.; Walker, D.A. Characteristics of cryogenic soils along a latitudinal transect in Arctic Alaska. J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 28917–28928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaminder, J.; Yoo, K.; Giesler, R. Soil carbon accumulation in the dry tundra: Important role played by precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, G04005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.; Jiskra, M.; Biester, H.; Chow, J.; Obrist, D. Mercury in active-layer tundra soils of Alaska: Concentrations, pools, origins, and spatial distribution. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2018, 32, 1058–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodygin, E.D.; Beznosikov, V.A.; Vanchikova, E.V. Functional groups of fulvic acids from gleyic peaty-podzolic soil. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2001, 34, 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Lodygin, E.; Vasilevich, R. Environmental aspects of molecular composition of humic substances from soils of northeastern European Russia. Pol. Polar Res. 2020, 41, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrist, D. Mercury distribution across 14 U.S. forests. Part II: Patterns of methyl mercury concentrations and areal mass of total and methyl mercury. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5921–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarbier, B.; Hugelius, G.; Sannel, A.B.K.; Baptista-Salazar, C.; Jonsson, S. Permafrost thaw increases methylmercury formation in subarctic Fennoscandia. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 6710–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodygin, E.D. Sorption of Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions by humic acids of tundra peat gley soils (Histic Reductaquic Cryosols). Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meili, M. The coupling of mercury and organic matter in the biogeochemical cycle—Towards a mechanistic model for the boreal forest zone. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1991, 56, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrist, D.; Agnan, Y.; Jiskra, M.; Olson, C.L.; Colegrove, D.P.; Hueber, J.; Moore, C.W.; Sonke, J.E.; Helmig, D. Tundra uptake of atmospheric elemental mercury drives Arctic mercury pollution. Nature 2017, 547, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravichandran, M. Interactions between mercury and dissolved organic matter—A review. Chemosphere 2004, 55, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Lin, C.-J.; Feng, X. Mercury accumulation and sequestration in a deglaciated forest chronosequence: Insights from particulate and mineral-associated forms of organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 16512–16521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfhus, K.R.; Hurley, J.P.; Bodaly, R.A.; Perrine, G. Production and retention of methylmercury in inundated boreal forest soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3482–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryazanov, M.A.; Lodygin, E.D.; Beznosikov, V.A.; Zlobin, D.A. Evaluation of the acid–base properties of fulvic acids using pK spectroscopy. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2001, 34, 830–836. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann, C.; Arnoldussen, A.; Englmaier, P.; Filzmoser, P.; Finne, T.E.; Garrett, R.G.; Koller, F.; Nordgulen, Ø. Element concentrations and variations along a 120 km long transect in south Norway—Anthropogenic vs. geogenic vs. biogenic element sources and cycles. Appl. Geochem. 2007, 22, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilevich, M.I.; Smirnov, N.S. Effect of atmospheric circulation on the seasonal dynamics of the chemical composition of the snow cover in the Pechora-Ilych reserve. Geochem. Int. 2024, 62, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockhoff, M.; Marginson, H.; Ittulak, H.; Roy, A.; Amyot, M. Influence of vegetative cover on snowpack mercury speciation and stocks in the greening Canadian subarctic region. Environ. Res. 2025, 264, 120333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Cartagena, E.; Morillas, H.; Carrero, J.A.; Madariaga, J.M.; Maguregui, M. Naturally growing grimmiaceae family mosses as passive biomonitors of heavy metals pollution in urban-industrial atmospheres from the Bilbao Metropolitan area. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanPiN 1.2.3685-21; Hygienic Norms and Requirements to Ensure Safety and/or Harmlessness of Living Environment Factors for Humans. Ministry of Health of Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2022. (In Russian)

- Department for Environment; Food and Rural Affairs. Part 2A Contaminated Land Statutory Guidance. In Environmental Protection Act 1990; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra): London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Halbach, K.; Mikkelsen, Ø.; Berg, T.; Steinnes, E. The presence of mercury and other trace metals in surface soils in the Norwegian Arctic. Chemosphere 2017, 188, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, C.I.; Geyman, B.M.; Thackray, C.P.; Krabbenhoft, D.P.; Tate, M.T.; Sunderland, E.M.; Driscoll, C.T. Mercury in soils of the conterminous United States: Patterns and pools. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 074030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME). Canadian Soil Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Environmental and Human Health. Mercury (Inorganic); Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines; Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1999; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Y. Organic carbon controls mercury distribution and storage in the surface soils of the water-level-fluctuation zone in the Three Gorges Reservoir Region, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevedrov, N.P.; Protsenko, E.P.; Glebova, I.V. The relationship between bulk and mobile forms of heavy metals in soils of Kursk. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2018, 51, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittman, J.A.; Shanley, J.B.; Driscoll, C.T.; Aiken, G.R.; Chalmers, A.T.; Towse, J.E.; Selvendiran, P. Mercury dynamics in relation to dissolved organic carbon concentration and quality during high flow events in three northeastern U.S. streams. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W07522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, R.; Han, G.; Liu, M.; Li, X. The mercury behavior and contamination in soil profiles in Mun River Basin, Northeast Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kleja, D.B.; Biester, H.; Lagerkvist, A.; Kumpiene, J. Influence of particle size distribution, organic carbon, pH and chlorides on washing of mercury contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2014, 109, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zharikova, E.A. Geochemical characterization of soils of the eastern coast of the Northern Sakhalin Lowland. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2017, 50, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, A.; Ran, S.; He, T.; Yin, D.; Xu, Y. The effects of different soil component couplings on the methylation and bioavailability of mercury in soil. Toxics 2023, 11, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Allen, H.E.; Li, Y.; Huang, C.P.; Sanders, P.F. Adsorption of mercury (II) by soil: Effects of pH, chloride, and organic matter. J. Environ. Qual. 1996, 25, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodygin, E. Landscape-geochemical assessment of content of natural hydrocarbons in arctic and subarctic soils (Komi Republic, Russia). Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J.; Cox, V.C. The effects of pH and chloride concentration on mercury adsorption. I. By goethite. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1992, 43, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamrikova, E.V.; Kazakov, V.G.; Sokolova, T.A. Variation in the acid-base parameters of automorphic loamy soils in the taiga and tundra zones of the Komi Republic. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2011, 44, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshelev, A.V.; Kaabak, L.V.; Golovkov, V.F.; Belikov, V.A.; Derevyagina, I.D.; Eleev, J.A.; Glukhan, E.N. Transformations of mercury compounds in the environment and its binding by organic substances of humic origin. Chem. Tech. Org. Sub. 2020, 4, 77–88. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Soriano, M.C.; Jimenez-Lopez, J.C. Effects of soil water content and organic matter addition on the speciation and bioavailability of heavy metals. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 423, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Soils | Horizons | Depth, cm | pH (H2O) | SOC, % | Clay (<0.01 mm), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stagnic Cambisols | O | 0–7 | 4.8 | 40.9 | – * |

| G | 20–50 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 37 | |

| Bg | 50–90 | 5.4 | 0.86 | 40 | |

| Histic Gleysols | O | 0–21 | 5.8 | 32.6 | – |

| G | 21–40 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 33.8 | |

| Bg | 60–95 | 6.1 | 0.55 | 28.4 | |

| Histic Cryosols | O | 0–41 | 5.7 | 18.7 | – |

| G | 41–55 | 6.1 | 0.89 | 31.6 | |

| Gf | 55–70 | 5.3 | 1.14 | 28.3 | |

| Entic Podzols | A0 | 0–4 | 4.2 | 8.3 | – |

| Eg | 4–18 | 4.6 | 0.21 | 1.6 | |

| Bhf | 18–65 | 5.0 | 0.21 | 3.6 | |

| Folic Stagnic Retisols | O | 0–12 | 4.8 | 39.4 | – |

| Eg | 15–40 | 5.1 | 0.85 | 13.7 | |

| Bg | 50–140 | 5.6 | 0.17 | 26.2 | |

| Histic Stagnic Retisols | O | 0–30 | 4.5 | 35.6 | – |

| Ehg | 30–40 | 4.8 | 10.6 | 12.1 | |

| Bg | 55–90 | 6.0 | 0.36 | 23 | |

| Albic Podzols | A0 | 0–4 | 4.3 | 25.4 | – |

| Eg | 4–10 | 3.9 | 0.86 | 2.5 | |

| Bf | 10–50 | 4.8 | 0.61 | 6.2 | |

| Stagnic Podzols | O | 0–10 | 4.9 | 22.2 | – |

| Ehg | 10–25 | 5.0 | 1.11 | 3.6 | |

| Bg | 25–60 | 5.0 | 0.44 | 2.6 | |

| Fibric Histosols | O | 0–20 | 4.4 | 55.7 | – |

| H | 20–50 | 4.3 | 60.7 | – | |

| Chg | 95–110 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 33.6 | |

| Umbric Fluvisols | A0 | 0–5 | 5.2 | 1.21 | 12.4 |

| A1 | 5–20 | 5.4 | 1.18 | 9.5 |

| Soils | Horizon | n | ωmin–ωmax | ±S | V, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stagnic Cambisols | O | 20 | 28–210 | 100 cd | 70 | 70.5 | 4.36 | 0.69 |

| G | 12 | 14–20 | 17 | 5 | 17.6 | – | – | |

| Bg | 12 | 18–23 | 21 | 5 | 10.1 | – | – | |

| Histic Gleysols | O | 20 | 104–200 | 150 e | 40 | 20.3 | 5.01 | 0.21 |

| G | 12 | 14–22 | 19 | 6 | 23.9 | – | – | |

| Bg | 12 | 18–23 | 25 | 8 | 22.3 | – | – | |

| Histic Cryosols | O | 15 | 46–150 | 110 d | 40 | 30.2 | 4.65 | 0.37 |

| G | 9 | 11–18 | 14 | 5 | 24.5 | – | – | |

| Gf | 9 | 17–27 | 20 | 6 | 20.6 | – | – | |

| Entic Podzols | A0 | 10 | 20–80 | 60 bc | 30 | 46.5 | 3.91 | 0.61 |

| Eg | 6 | 5–11 | 7 | 4 | 24.5 | – | – | |

| Bhf | 6 | 7–15 | 12 | 4 | 27.7 | – | – | |

| Folic Stagnic Retisols | O | 10 | 70–210 | 160 e | 50 | 29.9 | 5.04 | 0.40 |

| Eg | 6 | 16–28 | 22 | 7 | 21.4 | – | – | |

| Bg | 6 | 30–48 | 37 | 11 | 19.7 | – | – | |

| Histic Stagnic Retisols | O | 10 | 80–200 | 130 de | 50 | 34.4 | 4.83 | 0.34 |

| Ehg | 6 | 18–36 | 27 | 10 | 27.4 | – | – | |

| Bg | 6 | 22–43 | 33 | 11 | 23.0 | – | – | |

| Albic Podzols | A0 | 10 | 18–46 | 32 b | 11 | 35.8 | 3.40 | 0.39 |

| Eg | 6 | 5–9 | 5.8 | 2.1 | 27.5 | – | – | |

| Bf | 6 | 5–12 | 9 | 3 | 27.1 | – | – | |

| Stagnic Podzols | O | 10 | 28–70 | 43 b | 23 | 47.8 | 3.69 | 0.44 |

| Ehg | 6 | 6–13 | 10 | 3 | 25.1 | – | – | |

| Bg | 6 | 8–20 | 15 | 6 | 31.0 | – | – | |

| Fibric Histosols | O | 15 | 34–117 | 80 c | 30 | 33.2 | 4.41 | 0.26 |

| H | 9 | 39–120 | 80 c | 30 | 37.2 | – | – | |

| Chg | 9 | 17–33 | 21 | 8 | 29.3 | – | – | |

| Umbric Fluvisols | A0 | 10 | 7–26 | 18 a | 9 | 42.6 | 2.88 | 0.58 |

| A1 | 6 | 5–20 | 14 | 7 | 41.6 | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lodygin, E. Spatial Patterns of Mercury and Geochemical Baseline Values in Arctic Soils. Soil Syst. 2026, 10, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010014

Lodygin E. Spatial Patterns of Mercury and Geochemical Baseline Values in Arctic Soils. Soil Systems. 2026; 10(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleLodygin, Evgeny. 2026. "Spatial Patterns of Mercury and Geochemical Baseline Values in Arctic Soils" Soil Systems 10, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010014

APA StyleLodygin, E. (2026). Spatial Patterns of Mercury and Geochemical Baseline Values in Arctic Soils. Soil Systems, 10(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010014