Second Trimester Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

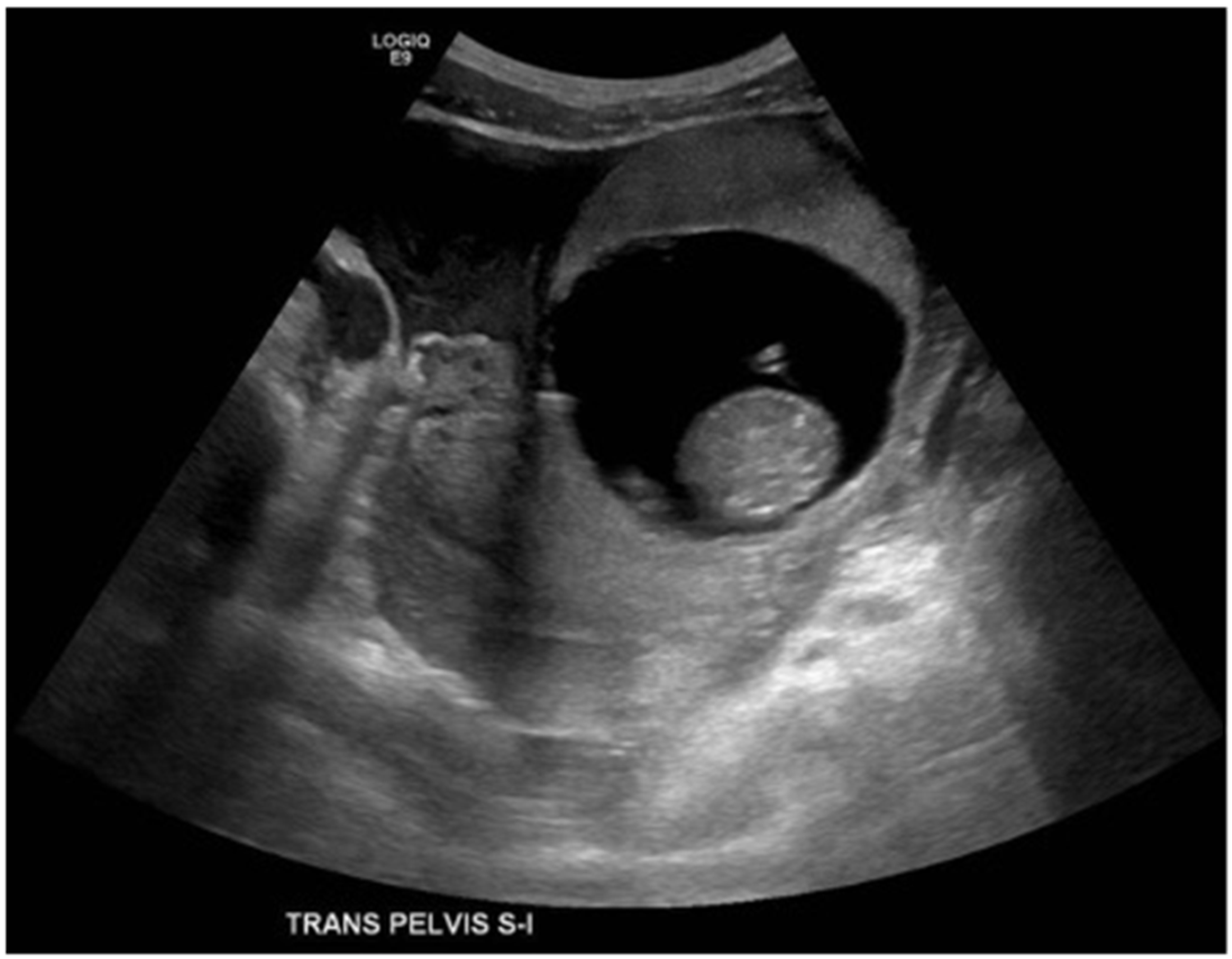

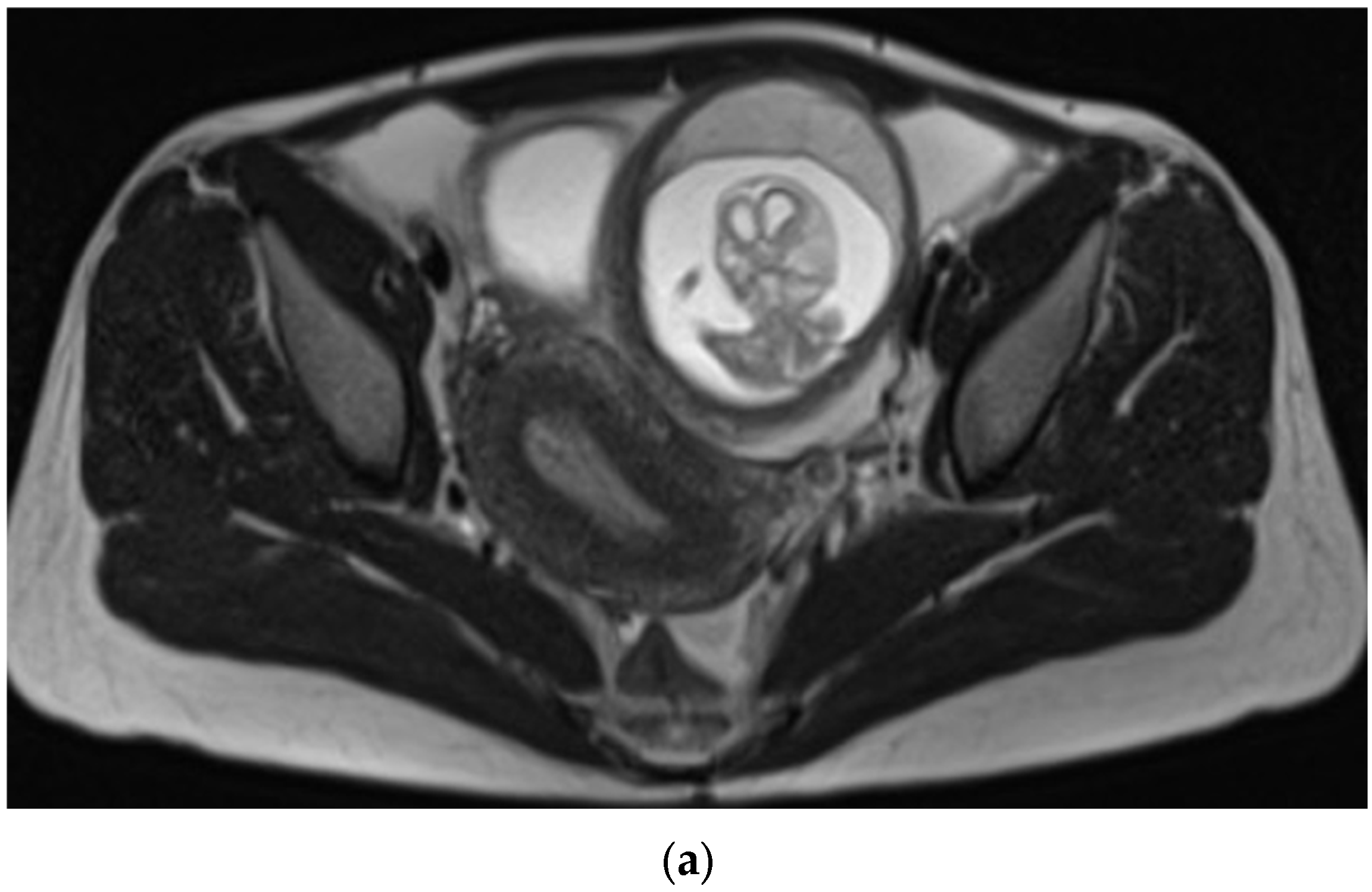

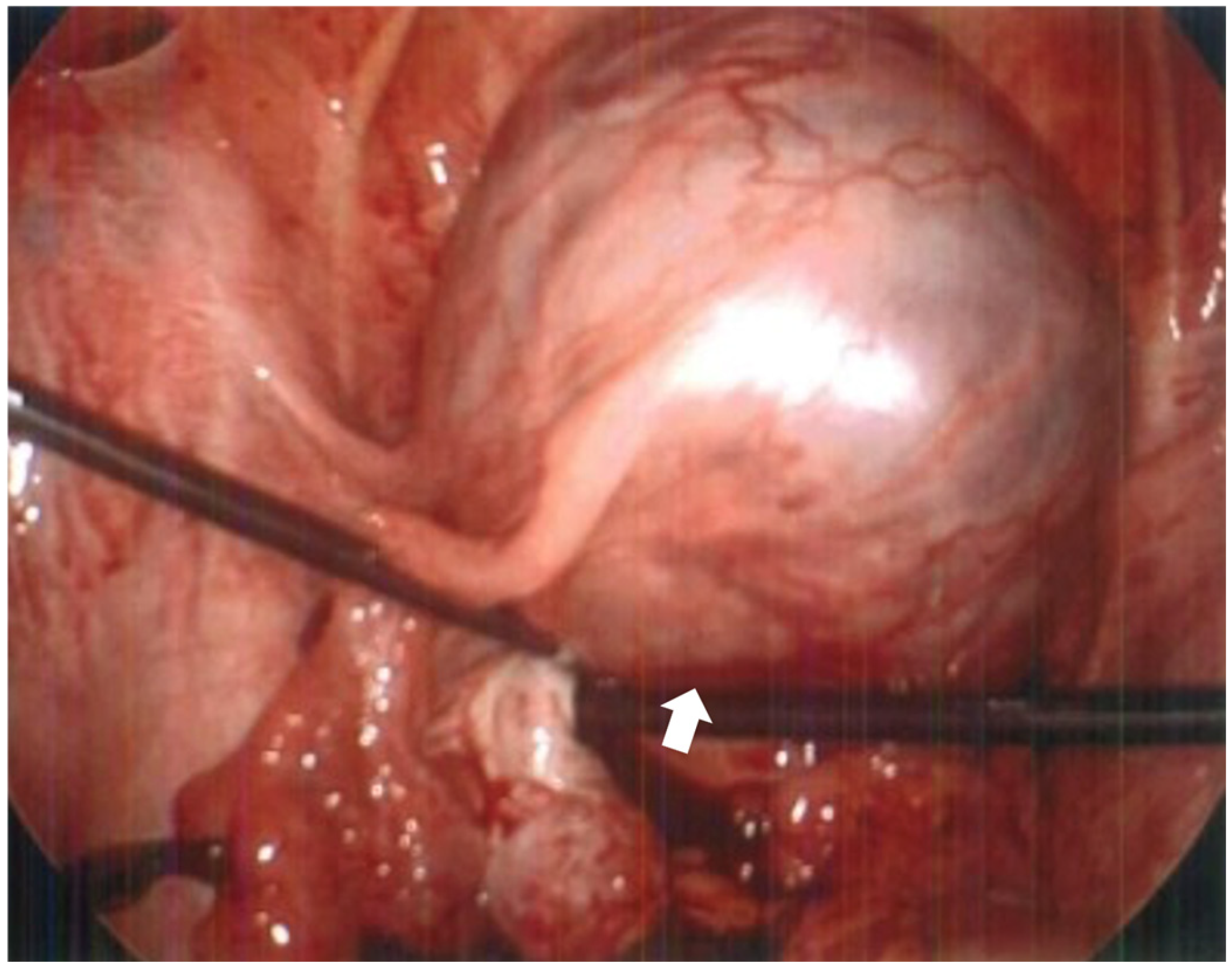

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IEP | Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

References

- Kampioni, M.; Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Wszołek, K.; Wilczak, M. Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy—Case Reports and Medical Management. Medicina 2023, 59, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bahall, V.; Cozier, W.; Latchman, P.; Elias, S.A.; Sankar, S. Interstitial ectopic pregnancy rupture at 17 weeks of gestation: A case report and literature review. Case Rep. Women’s Health 2022, 36, e00464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, A.S.; Taha, M.S. Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy, Diagnosis and Management: A Case Report and Literature Review. Ann. Clin. Case Rep. 2017, 2, 1352. [Google Scholar]

- Schraft, E.; Gottlieb, M. Near fatal interstitial pregnancy. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 57, 235.e5–235.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brincat, M.; Bryant-Smith, A.; Holland, T.K. The diagnosis and management of interstitial ectopic pregnancies: A review. Gynecol. Surg. 2019, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Chueh, H.Y.; Chang, S.D.; Yang, C.Y. Interstitial ectopic pregnancy: A more confident diagnosis with three-dimensional sonography. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 60, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.H. Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy, Visual Encyclopedia of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Available online: https://www.isuog.org/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Kao, L.Y.; Scheinfeld, M.H.; Chernyak, V.; Rozenblit, A.M.; Oh, S.; Dym, R.J. Beyond ultrasound: CT and MRI of ectopic pregnancy. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2014, 202, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, R.; Silva, C.; Tomé, A.; Pereira, E.; Regalo, A.F. Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy: A Rare Diagnosis. Cureus 2023, 15, e43107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kahramanoglu, I.; Mammadov, Z.; Turan, H.; Urer, A.; Tuten, A. Management options for interstitial ectopic pregnancies: A case series. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reyes, D.; Key, A.; LeBaron, Z.; Matz, S.; Gridley, D. Second Trimester Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy. Reports 2025, 8, 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040229

Reyes D, Key A, LeBaron Z, Matz S, Gridley D. Second Trimester Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy. Reports. 2025; 8(4):229. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040229

Chicago/Turabian StyleReyes, Daniel, Amanda Key, Zachary LeBaron, Samantha Matz, and Daniel Gridley. 2025. "Second Trimester Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy" Reports 8, no. 4: 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040229

APA StyleReyes, D., Key, A., LeBaron, Z., Matz, S., & Gridley, D. (2025). Second Trimester Interstitial Ectopic Pregnancy. Reports, 8(4), 229. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040229