Pembrolizumab-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma: Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

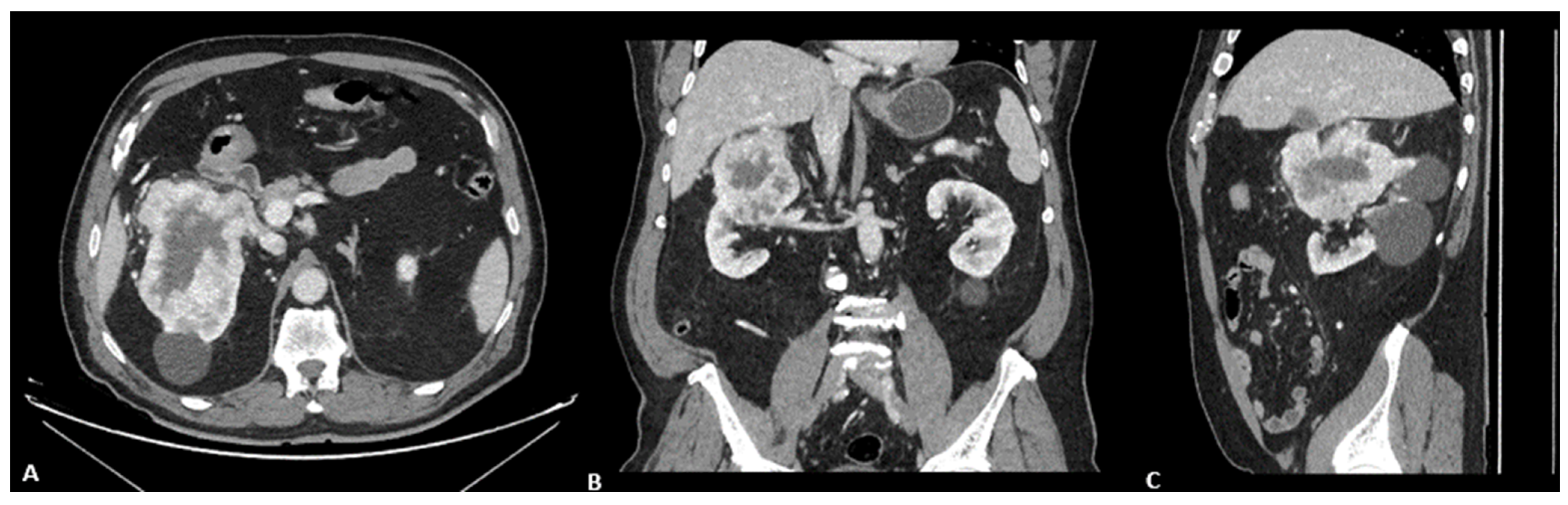

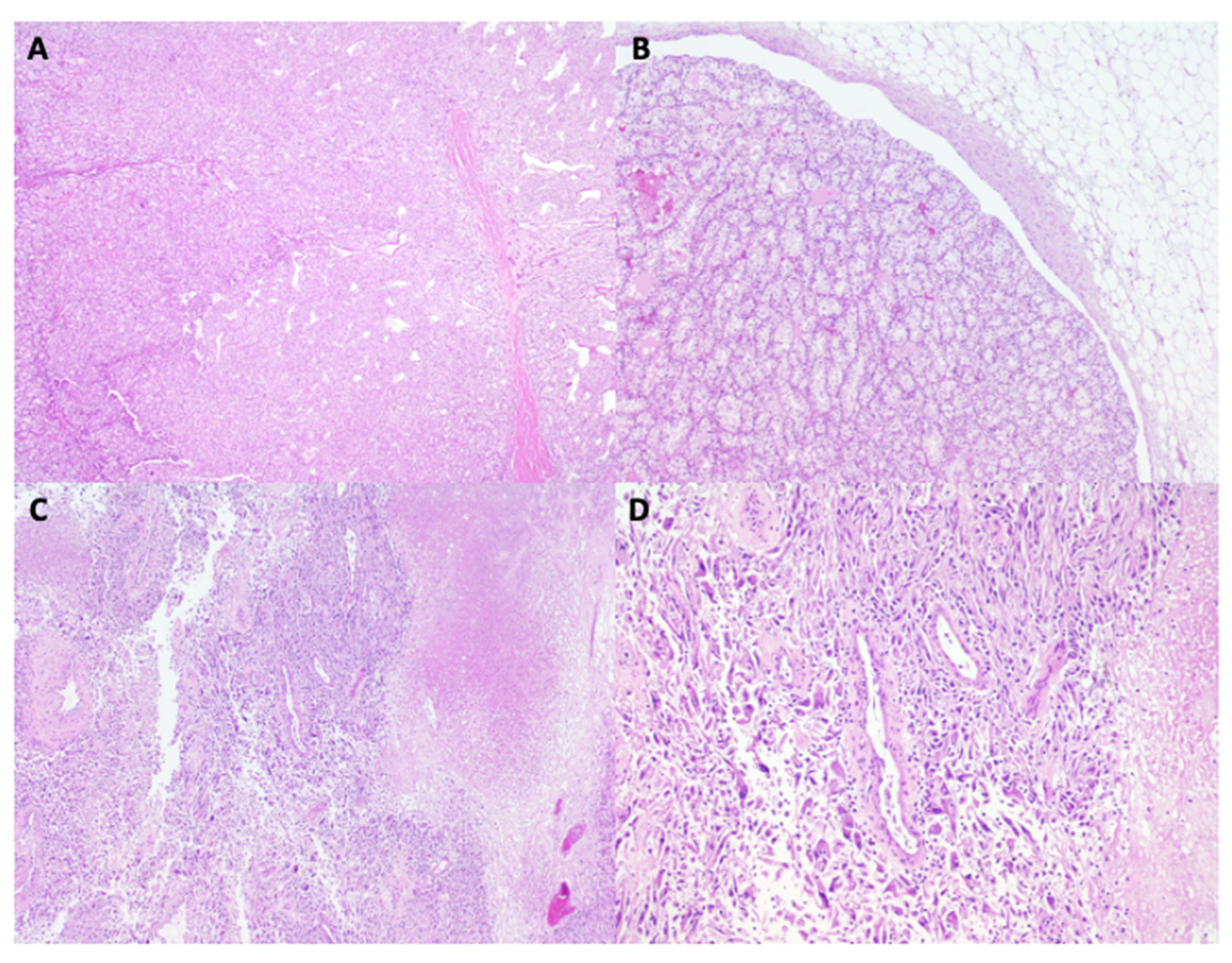

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barquín-García, A.; Molina-Cerrillo, J.; Garrido, P.; Garcia-Palos, D.; Carrato, A.; Alonso-Gordoa, T. New oncologic emergencies: What is there to know about inmunotherapy and its potential side effects? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Tomczak, P.; Park, S.H.; Venugopal, B.; Ferguson, T.; Symeonides, S.N.; Hajek, J.; Chang, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-L.; Sarwar, N.; et al. Overall Survival with Adjuvant Pembrolizumab in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naleid, N.; Mahipal, A.; Chakrabarti, S. Toxicity Associated with Pembrolizumab Monotherapy in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, L.; Monteith, B.; Heffernan, P.; Herzinger, T.; Wilson, B.E. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/cytokine release syndrome secondary to neoadjuvant pembrolizumab for triple-negative breast cancer: A case study. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1394543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardet, L.; Galicier, L.; Lambotte, O.; Marzac, C.; Aumont, C.; Chahwan, D.; Coppo, P.; Hejblum, G. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 2613–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmuk, J.; Puchalla, J.; Feng, G.; Giri, A.; Kaczmar, J. Pembrolizumab-induced Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: An immunotherapeutic challenge. Cancers Head Neck 2020, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Midorikawa, H.; Osawa, K.; Shirai, T.; Sano, T.; Kiniwa, Y.; Nakazawa, H.; Okuyama, R. Hemophagocytic syndrome associated with pembrolizumab therapy successfully controlled by cyclosporin. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, e422–e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daver, N.; McClain, K.; Allen, C.E.; Parikh, S.A.; Otrock, Z.; Rojas-Hernandez, C.; Blechacz, B.; Wang, S.; Minkov, M.; Jordan, M.B.; et al. A consensus review on malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Cancer 2017, 123, 3229–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J.; Hall, J.A.; Reely, K.; Dodlapati, J. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to pembrolizumab therapy for adenocarcinoma of the lung. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2021, 34, 729–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Jin, X.; You, L.; Yan, N.; Dong, J.; Qiao, S.; Zhong, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, H. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis following pembrolizumab and bevacizumab combination therapy for cervical cancer: A case report and systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; He, W.; Sun, W.; Wu, C.; Ren, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Huang, M.; Ji, N. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in two patients following treatment with pembrolizumab: Two case reports and a literature review. Transl. Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 2960–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Koiwa, T.; Fujita, A.; Suzuki, T.; Tagashira, A.; Iwasaki, Y. A case of pembrolizumab-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis successfully treated with pulse glucocorticoid therapy. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 30, 101097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaat, M.; Jang, S. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with immunotherapy: Brief review and case report. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samkari, H.; Snyder, G.D.; Nikiforow, S.; Tolaney, S.M.; Freedman, R.A.; Losman, J.-A. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicating pembrolizumab treatment for metastatic breast cancer in a patient with the PRF1A91V gene polymorphism. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmes, G.L.; Nigdelis, M.P.; Hamoud, B.H.; Solomayer, E.-F.; Bewarder, M.; Bittenbring, J.T.; Kranzhöfer, N.; Thurner, L.; Kim, Y.-J.; Seibold, A.; et al. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with adjuvant pembrolizumab therapy in a young patient with triple-negative breast cancer: A case report with literature review. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. Obstet. 2025, 312, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, Y.; Awano, N.; Inomata, M.; Kuse, N.; Tone, M.; Yoshimura, H.; Jo, T.; Takada, K.; Kumasaka, T.; Izumo, T. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in a Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis on Pembrolizumab for Lung Adenocarcinoma. Intern. Med. 2020, 59, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marar, R.; Prathivadhi-Bhayankaram, S.; Krishnan, M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in a Patient With Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Hematol. 2022, 11, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, T.; Naito, H.; Osaki, Y.; Tohi, Y.; Matsuoka, Y.; Kato, T.; Okazoe, H.; Taoka, R.; Ueda, N.; Sugimoto, M. A Case of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis During Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma, Complicated by Pancytopenia Attributed to Cytomegalovirus Infection. IJU Case Rep. 2025, 8, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignon, P.; Nguyen, L.D.K.; Boegner, P.; Ku, J.; Herpain, A. Refractory insulin resistance and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis following enfortumab vedotin treatment: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| DATE | 10/08/23 | 17/01/24 | 06/02/24 | 09/02/24 | 15/02/24 | 16/02/24 | 20/02/24 | 24/02/24 | 27/02/24 | 28/02/24 | 29/02/24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine mg/dL | 2.25 | 1.82 | 2.01 | 2.16 | 1.48 | 1.42 | 1.54 | 1.65 | 1.58 | 1.71 | 2.88 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) ml/min/1.73 m2 | 27 | 34 | 30 | 28 | 44 | 46 | 42 | 39 | 41 | 37 | 20 |

| LDH U/L | 127 | 155 | 304 | 338 | 375 | 308 | 555 | 463 | 1021 | 1803 | 3640 |

| Total bilirrubin mg/dL | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 9.9 |

| Direct bilirrubin mg/dL | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.6 | 2.5 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 7.6 |

| GGT U/L | 194 | 435 | 428 | 337 | 680 | 545 | 729 | 716 | 521 | 542 | 482 |

| Alkaline phosphatase U/L | 137 | 227 | 153 | 127 | 209 | 166 | 230 | 223 | 197 | 240 | 281 |

| Albumin g/dL | 4.3 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3 | 3.1 |

| NTproBNP (pg/mL) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6984 |

| C reactive protein (CRP) | NA | 4.14 | 8.99 | 22.47 | 19.5 | 8.62 | 18.17 | 6.7 | 21.95 | 23.81 | 32.11 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | NA | NA | 0.31 | NA | 0.55 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7.29 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 134 | NA | NA | NA | 209 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.1 | 10.7 | 12.9 | 10.7 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 8 | 8.9 | 9.6 |

| Leukocytes /µL (×109/L) | 3290 | 2780 | 2140 | 580 | 720 | 810 | 460 | 840 | 380 | 480 | 440 |

| Neutrophils /µL (×109/L) | 1740 | 2080 | 1500 | 440 | 390 | 590 | 250 | 630 | 260 | 260 | 100 |

| Platelets /µL (×109/L) | 127,000 | 321,000 | 124,000 | 78,000 | 72,000 | 84,000 | 66,000 | 73,000 | 27,000 | 19,000 | 42,000 |

| IL-2 (U/mL) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | >7500 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 239 | NA | NA | 4618 | NA | NA | NA | 6575 | 20,074 | 49,274 | NA |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 287.6 | NA | NA | 151.8 | NA | 233.8 | NA |

| Author | Gender | Age | Pembrolizumab Cycles | Time to Onset | Line of Therapy | HLH Treatment | Tumor Type | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalmuk et al. (2020) [7] | Male | 61 | 14 | 74 weeks | 1 | Methylprednisolone Dexamethasone 10 mg/m2 Etoposide 150 mg/m2 | Squamous cell orofaringe | No. Immunotherapy was restarted. |

| J.Doyle et al. (2021) [10] | Male | 71 | 14 | 42 weeks | 1 | NA | Lung adenocarcinoma | No. Switch to another line of therapy. |

| Zhai et al. (2024) [11] | Woman | 73 | 1 | 1 week | 1 | Methylprednisolone, posaconazole, and caspofungin * | Squamous cell carcinoma cervix | No. Alive at 6 months. |

| Wei et al. (2022) [12] | Woman | 50 | 1 | 1 week | 2 | Oral methylprednisolone and azathioprin | Thymic carcinoma | No. Alive at 14 months. |

| Wei et al. (2022) [12] | Male | 70 | 1 | 2 weeks | 1 | Methylprednisolone Dexamethasone 10 mg/m2 Etoposide 150 mg/m2 | Squamous cell lung | No. Alive at 8 months. |

| Takahasi et al. (2020) [13] | Male | 78 | 1 | 1 week | 2 | Methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for 3 days) After the pulse steroid therapy, he received 60 mg/day (1 mg/kg/day) of prednisolone, which was tapered to 50 mg/day within 4 weeks | Lung adenocarcinoma | No |

| Sadaat et al. (2018) [14] | Male | 58 | 6 | 20 weeks | 1 | High-dose glucocorticoids, steroid dose was tapered over 7 weeks | Melanoma | No. Complete response for 1 year. |

| Al-Samkari et al. (2018) [15] | Woman | 58 | 5 | 15 weeks | 2 | Methylprednisolone taper (initial dose 1 g, with slow taper over the following weeks) (No etoposide given due to observed improvement) | Breast cancer | No. Resolution of the condition. PRF1A91V gene polymorphism Included in Keynote NCT02513472 |

| G.L olmes et al. (2025) [16] | Woman | 32 | 11 | 33 weeks | 1 (adyuvant) | Prednisolone orally 100 mg once daily | Breast cancer | No. Resolution of the condition. |

| Patton et al. (2024) [5] | Woman | 40 | 4 | 12 weeks | 1 (neoadyuvant) | Methylprednisolone 100 mg/day Tocilizumab (8 mg/kg), 2 doses | Breast cancer | No. Response to tocilizumab. Required intubation. |

| Akagi et al. (2020) [17] | Male | 74 | 1 | 4 weeks | 2 | Dexamethasone 10 mg/m2 Etoposide 150 mg/m2 | Lung adenocarcinoma | No. |

| Marar et al. (2022) [18] | Woman | 80 | 6 | 22 weeks | 1 | 1 mg/kg methylprednisolone dexamethasone 10 mg/kg tocilizumab at 4 mg/kg 2 doses | SCC | No. Resolution of the condition. |

| Honda et al. (2025) [19] | Male | 63 | 1 | 2 weeks | 1 (plus lenvatinib) | Methylprednisolone 1000 mg/day mycophenolate mofetil was initiated at 1000 mg/day and escalated to 2000 mg/ day over 3 days Ganciclovir (positive citomegalovirus due to immunosupresion) | Clear cell renal cell carcinoma | No Primary tumor resected after 6 months; died from pleural effusion 1 month after surgery. |

| Rossignon et al. (2024) [20] | Male | 56 | NE | It developed after discontinuation of pembrolizumab. The patient was receiving third-line therapy with enfortumab vedotin (E–V). | 2 | Dexamethasone Etoposide | Metastatic urothelial carcinoma | Yes. Patient death after 28 days of hospitalization. |

| Fever ≥ 38.5 °C |

|---|

| Splenomegaly |

| Two or more cytopenias (hemoglobin < 9 g/dL, neutrophils < 1000/µL, platelets < 100,000/µL) |

| Hypofibrinogenemia < 150 mg/dL and/or hypertriglyceridemia > 265 mg/dL |

| Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, lymph node, or liver |

| Low or absent natural killer (NK) cell activity |

| Ferritin > 500 ng/mL |

| Elevated soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor alpha) > 2400 U/mL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinto Valdivia, R.; Posado-Domínguez, L.; Iglesias, M.E.; Antúnez Plaza, P.; Fonseca-Sánchez, E. Pembrolizumab-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma: Case Report and Literature Review. Reports 2025, 8, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040256

Pinto Valdivia R, Posado-Domínguez L, Iglesias ME, Antúnez Plaza P, Fonseca-Sánchez E. Pembrolizumab-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma: Case Report and Literature Review. Reports. 2025; 8(4):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040256

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto Valdivia, Romina, Luis Posado-Domínguez, Maria Escribano Iglesias, Patricia Antúnez Plaza, and Emilio Fonseca-Sánchez. 2025. "Pembrolizumab-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma: Case Report and Literature Review" Reports 8, no. 4: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040256

APA StylePinto Valdivia, R., Posado-Domínguez, L., Iglesias, M. E., Antúnez Plaza, P., & Fonseca-Sánchez, E. (2025). Pembrolizumab-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma: Case Report and Literature Review. Reports, 8(4), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8040256