MSSA Thoracic Mycotic Aneurysm Repaired with TEVAR: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

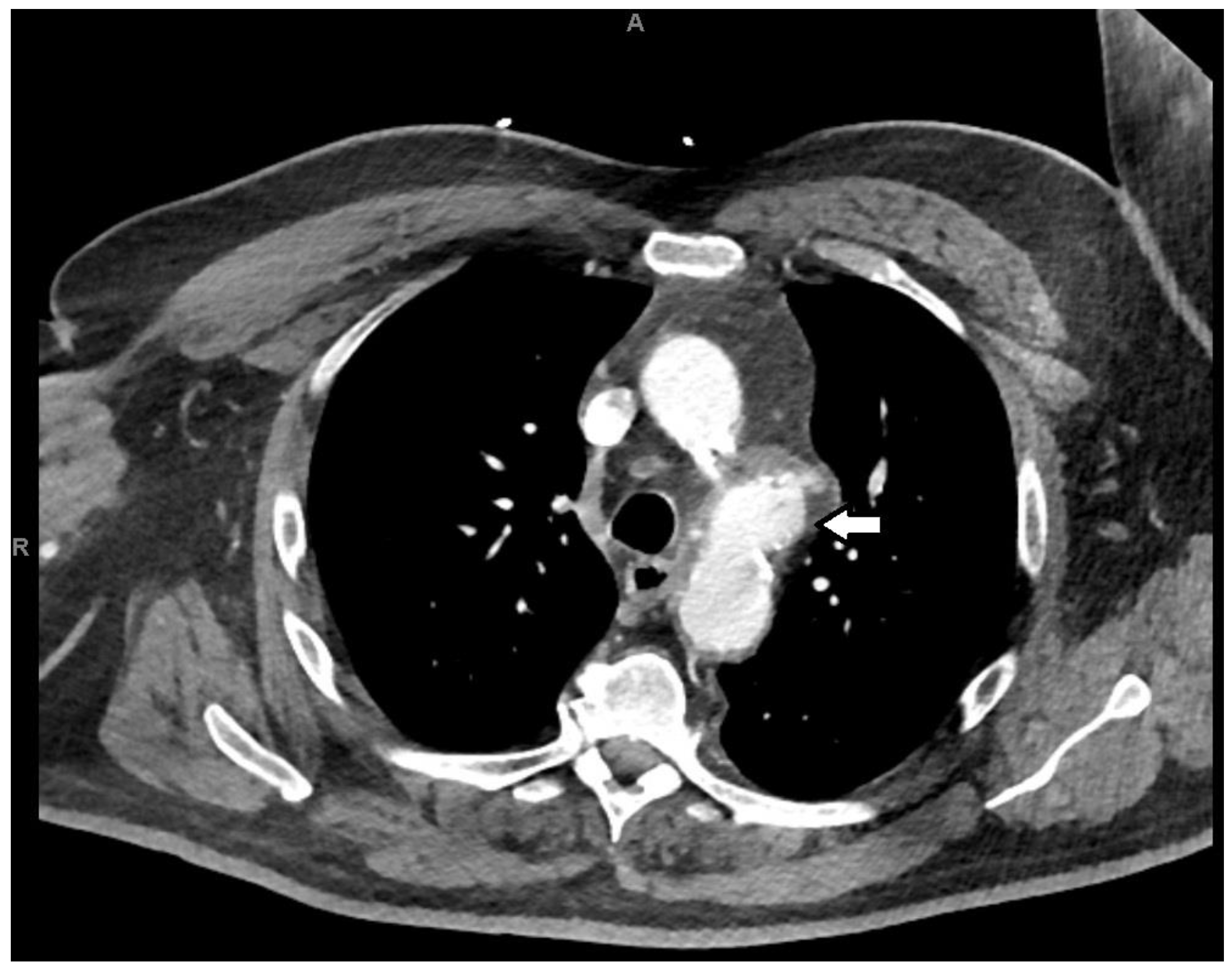

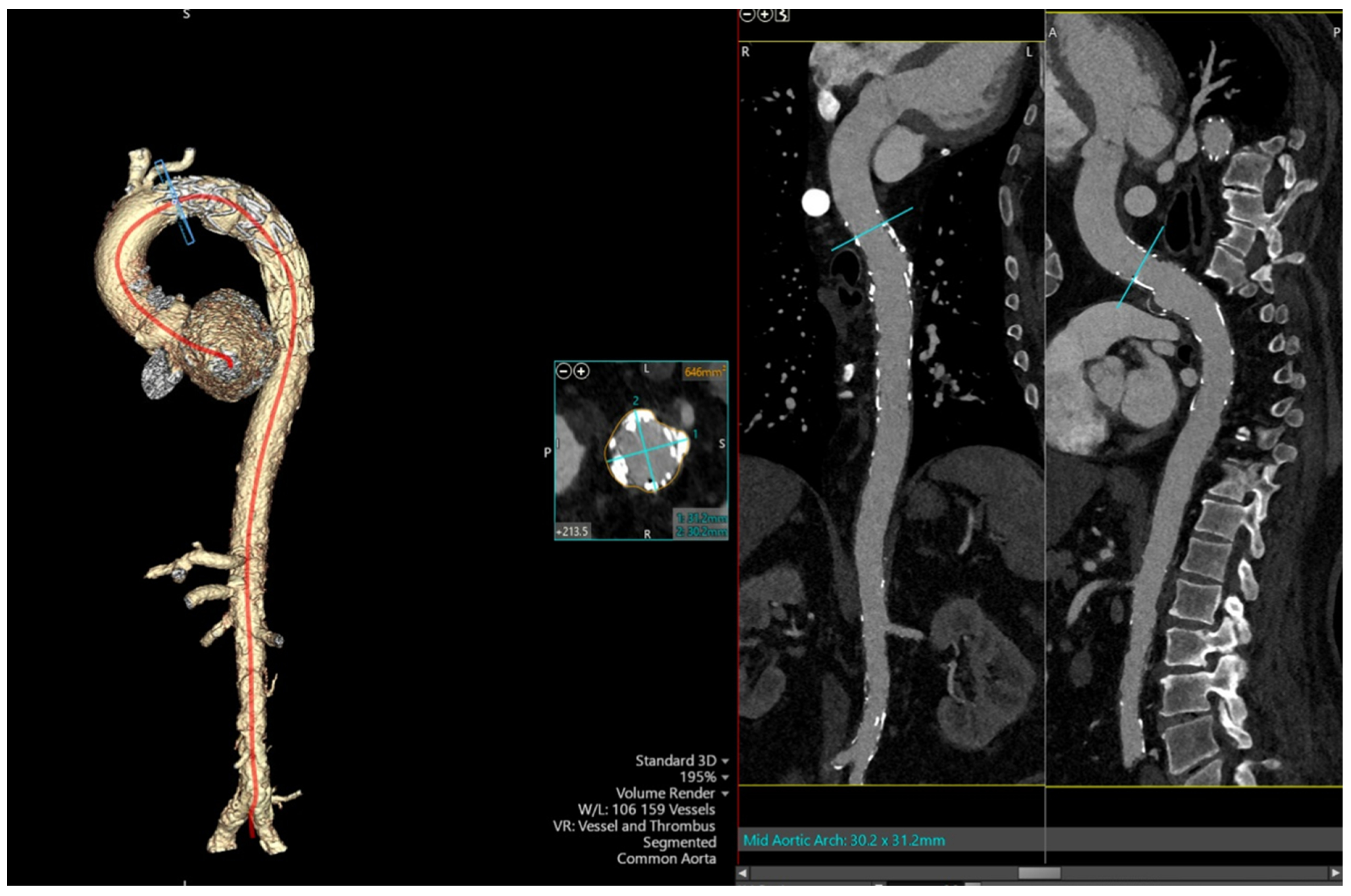

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, W.-K.; Mossop, P.J.; Little, A.F.; Fitt, G.J.; Vrazas, J.I.; Hoang, J.K.; Hennessy, O.F. Infected (mycotic) aneurysms: Spectrum of imaging appearances and management. Radiographics 2008, 28, 1853–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raavi, L.; Garg, P.; Hussain, M.W.A.; Wadiwala, I.J.; Mateen, N.T.; Elawady, M.S.; Alomari, M.; Alamouti-fard, E.; Pham, S.M.; Jacob, S. Mycotic thoracic aortic aneurysm: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Cureus 2022, 14, e31010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soravia-Dunand, V.A.; Loo, V.G.; Salit, I.E. Aortitis due to Salmonella: Report of 10 cases and comprehensive review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999, 29, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, N.E.A.; Vedantham, S.; Gould, J.E. Challenge. In Vascular and Interventional Imaging; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 187–280. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, W.R.; Bower, T.C.; Creager, M.A.; Amin-Hanjani, S.; O’gAra, P.T.; Lockhart, P.B.; Darouiche, R.O.; Ramlawi, B.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Bolger, A.F.; et al. Vascular graft infections, mycotic aneurysms, and endovascular infections: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2016, 134, e412–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osler, W. The gulstonian lectures, on malignant endocarditis. BMJ 1885, 1, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.J.; Almeida, J.; Dias, P.J.; Pinho, P.; Maciel, M.J. Infectious thoracic aortitis: A literature review. Clin. Cardiol. 2009, 32, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, B.O.; Mancusi, C.; Coscarella, C.; Spataro, C.; Carfagna, P.; Ippoliti, A.; Giudice, R.; Ferrer, C. Urgent or emergent endovascular aortic repair of infective aortitis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.-M.; Chang, H.-H.; Hsu, C.-P.; Lai, S.-T.; Shih, C.-C. Ten-year experience with surgical repair of mycotic aortic aneurysms. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2005, 68, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, H.; Sudo, Y.; Ukita, H. Bacteremia causes mycotic aneurysm of the aortic arch in 110 days. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007, 83, 1874–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isselbacher, E.M.; Preventza, O.; Black, J.H., 3rd; Augoustides, J.G.; Beck, A.W.; Bolen, M.A.; Braverman, A.C.; Bray, B.E.; Brown-Zimmerman, M.M.; Chen, E.P.; et al. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of Aortic Disease: A report of the American heart association/American college of cardiology joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2022, 146, e334–e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badshah, A.; Younas, F.; Janjua, M. Infective mycotic aneurysm presenting as transient acute coronary occlusion and infectious pericarditis. South. Med. J. 2009, 102, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wal, H.; van Geel, P.P.; Deber, R.A. Mycotic aneurysm of the aorta as an unusual complication of coronary angiography. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2008, 36, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.-M. Hoarseness due to aortic arch aneurysms. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 35, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokmaji, G.; Gosev, I.; Kumamaru, K.K.; Bolman, R.M., 3rd. Mycotic aneurysm of the aortic arch presenting with left vocal cord palsy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 96, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steverlynck, L.; Van de Walle, S. Mycotic thoracic aortic aneurysm: Review of the diagnostic and therapeutic options. Acta Clin. Belg. 2013, 68, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.K.M.; Griffin, B.; Cremer, P.; Shrestha, N.; Gordon, S.; Pettersson, G.; Desai, M. Diagnostic utility of CT and MRI for mycotic aneurysms: A meta-analysis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020, 215, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisk, M.; Peck, L.F.; Miyagi, K.; Steward, M.J.; Lee, S.F.; Macrae, M.B.; Morris-Jones, S.; Zumla, A.I.; Marks, D.J.B. Mycotic aneurysms: A case report, clinical review and novel imaging strategy. QJM 2012, 105, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malouf, J.F.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Orszulak, T.A. Mycotic aneurysms of the thoracic aorta: A diagnostic challenge. Am. J. Med. 2003, 115, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörelius, K.; Budtz-Lilly, J.; Mani, K.; Wanhainen, A. Systematic review of the management of mycotic aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 58, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thirupathy, U.; Venkata, V.S.; Panchal, V. MSSA Thoracic Mycotic Aneurysm Repaired with TEVAR: A Case Report. Reports 2025, 8, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030184

Thirupathy U, Venkata VS, Panchal V. MSSA Thoracic Mycotic Aneurysm Repaired with TEVAR: A Case Report. Reports. 2025; 8(3):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030184

Chicago/Turabian StyleThirupathy, Umabalan, Vikramaditya Samala Venkata, and Viraj Panchal. 2025. "MSSA Thoracic Mycotic Aneurysm Repaired with TEVAR: A Case Report" Reports 8, no. 3: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030184

APA StyleThirupathy, U., Venkata, V. S., & Panchal, V. (2025). MSSA Thoracic Mycotic Aneurysm Repaired with TEVAR: A Case Report. Reports, 8(3), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030184