Extensive Cholesteatoma Compromising the Entire Ipsilateral Skull Base: Excision Through a Multi-Corridor Surgical Technique

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Presentation

2.1. History

2.2. CT Imaging and Surgical Planning

2.3. Two-Stage Surgical Procedure

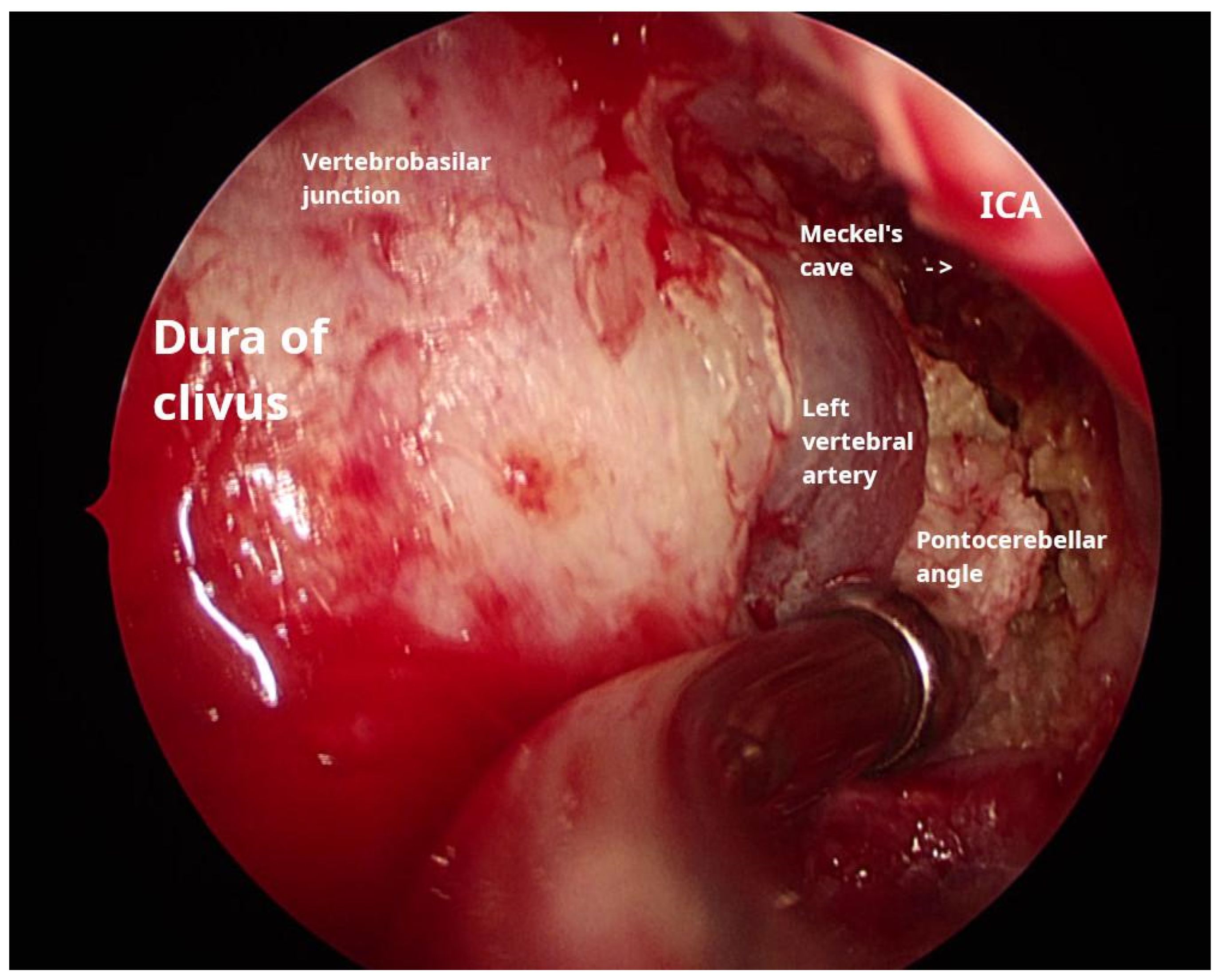

2.3.1. Transnasal Transclival Endoscopic Approach

2.3.2. Retrolabyrinthine Approach

2.4. Outcome and Follow-Up

2.5. Complications

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBC | Petrous bone cholesteatoma |

| IAC | Internal auditory canal |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| ICA | Internal carotid artery |

| CPA | Cerebellopontine angle |

| CT | Computer tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

References

- Sanna, M.; Pandya, Y.; Mancini, F.; Sequino, G.; Piccirillo, E. Petrous Bone Cholesteatoma: Classification, Management and Review of the Literature. Audiol. Neurotol. 2011, 16, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danesi, G.; Cooper, T.; Panciera, D.T.; Manni, V.; Côté, D.W.J. Sanna Classification and Prognosis of Cholesteatoma of the Petrous Part of the Temporal Bone. Otol. Neurotol. 2016, 37, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, G.; Sciarretta, V.; Calbucci, F.; Farneti, G.; Mazzatenta, D.; Pasquini, E. The Endoscopic Transnasal Transsphenoidal Approach for the Treatment of Cranial Base Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas. Oper. Neurosurg. 2006, 59, ONS-50–ONS-57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgalas, C.; Kania, R.; Guichard, J.-P.; Sauvaget, E.; Tran Ba Huy, P.; Herman, P. Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for cholesterol granulomas involving the petrous apex. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2008, 33, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubry, K.; Kovac, L.; Sauvaget, E.; Huy, P.T.B.; Herman, P. Our experience in the management of petrous bone cholesteatoma. Skull Base 2010, 20, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, Q.H.; Zuo, K.J.; Xu, G. Resection of petrous apex cholesteatoma via endoscopic trans-sphenoidal approach. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi Chin. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 47, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nishida, N.; Fujiwara, T.; Satoshi, S.; Inoue, A.; Takagi, D.; Takagi, T.; Hato, N. Exteriorization of Petrous Bone Cholesteatoma by Endonasal Endoscopic Approach: A Case Report. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2021, 17, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morino, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Komori, M.; Asaka, D.; Kojima, H. Management of Intractable Petrous Bone Cholesteatoma with a Combined Translabyrinthine-Transsphenoidal Approach. Otol. Neurotol. 2021, 42, e311–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, W.E.; Keyes, A.S.; Lanza, D.C. Use of the Superior Meatus and Superior Turbinate in the Endoscopic Approach to the Sphenoid Sinus. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1999, 120, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschuur, H.P.; de Wever, W.W.; van Benthem, P.P. Antibiotic prophylaxis in clean and clean-contaminated ear surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004, 2010, CD003996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eide, J.G.; Mason, W.; Mackie, H.; Cook, B.; Ray, A.; Asmaro, K.; Robin, A.; Rock, J.; Craig, J.R. Diagnostic Accuracy of Beta-2 Transferrin Gel Electrophoresis for Detecting Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea. Laryngoscope 2025, 135, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touska, P.; Connor, S.E.J. ESR Essentials: Imaging of middle ear cholesteatoma-practice recommendations by the European Society of Head and Neck Radiology. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 2053–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Approach | Lesion Location | Procedure Includes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtotal petrosectomy | Petrous bone | Canal-wall-down tympanomastoidectomy, fallopian canal skeletonization, and surgical cavity obliteration | It enables wide access to the petrous apex and poses a lower risk of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak compared to other, similar approaches | It entails hearing loss and a risk of damage to the facial nerve, internal carotid artery (ICA), or jugular bulb |

| Middle fossa approach | Internal auditory canal (IAC), petroclival region, prepontine cisterns, and upper to middle clivus in extended approach | Craniotomy, elevation of dura and localization of landmarks (arcuate eminence and greater superficial petrosal nerve), IAC skeletonization, and nerve identification | It preserves hearing and is ideal for smaller-tumor resection | It facilitates limited exposure, entails temporal lobe retraction, and poses a risk of damage to the facial nerve |

| Translabyrinthine approach | IAC and cerebellopontine angle (CPA) | Mastoidectomy, posterior cranial fossa bone removal, labyrinthectomy, and skeletonization of the IAC | It offers a direct path to the IAC and allows access to the facial nerve along its segments | It entails hearing loss, CSF leakage and is hard to perform in the case of some anatomical variations (low tegmen, anterior sigmoid sinus, and high jugular bulb) |

| Transotic approach | CPA anterior to the IAC and petrous apex | Canal-wall-down tympanomastoidectomy, labyrinthectomy, fallopian canal, ICA and jugular bulb skeletonization, and surgical cavity obliteration | It allows near circumferential access to the IAC and porus and has a better chance of preserving the facial nerve | It facilitates reduced exposure compared to the transcochlear approach and poses a risk of ICA damage and possible CSF leakage |

| Transcochlear approach | Petrous apex, CPA, and clivus | Canal-wall-down tympanomastoidectomy, labyrinthectomy, drilling out of the cochlea and fallopian canal with rerouting of the facial nerve, ICA and jugular bulb skeletonization, and surgical cavity obliteration | It allows wide CPA exposure without brain retraction and grants access to CN V-XI and the vertebral and basilar arteries | It sacrifices residual hearing, poses a high risk of facial nerve damage, poses a risk of ICA damage, and potentially leads to CSF leakage |

| Infratemporal fossa approach type B | Petrous apex and clivus, petrous ICA, inferior temporal surface, and CN V-XII | Transection and closure of the EAC, division of the zygomatic arch, removal of the floor of the skull base, skeletonization of the petrous ICA, detachment of the eustachian tube, and obliteration of the surgical cavity | Enables wide exposure of lateral skull base | It entails conductive hearing loss, facial nerve damage, and possible mandible dislocation |

| Endoscopic transsphenoidal transclival approach | Sphenoid sinus, sellar and parasellar region, clivus, ventral brainstem, and craniovertebral junction | Turbinatectomy, antrostomy, posterior ethmoidectomy, removal of the inferior sphenoid sinus wall, posterior septectomy, and drilling of the clivus | It is less invasive, potentially enables reconstruction with pedicled flaps, allows multilevel exposure (sellar, clival, and craniovertebral), and involves less manipulation of neurovascular structures | It poses a risk of CSF leakage, allows only limited lateral exposure, and requires training in skull base surgery |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rangachev, L.; Rangachev, J.; Marinov, T.; Skelina, S.; Popov, T.M. Extensive Cholesteatoma Compromising the Entire Ipsilateral Skull Base: Excision Through a Multi-Corridor Surgical Technique. Reports 2025, 8, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030148

Rangachev L, Rangachev J, Marinov T, Skelina S, Popov TM. Extensive Cholesteatoma Compromising the Entire Ipsilateral Skull Base: Excision Through a Multi-Corridor Surgical Technique. Reports. 2025; 8(3):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030148

Chicago/Turabian StyleRangachev, Lyubomir, Julian Rangachev, Tzvetomir Marinov, Sylvia Skelina, and Todor M. Popov. 2025. "Extensive Cholesteatoma Compromising the Entire Ipsilateral Skull Base: Excision Through a Multi-Corridor Surgical Technique" Reports 8, no. 3: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030148

APA StyleRangachev, L., Rangachev, J., Marinov, T., Skelina, S., & Popov, T. M. (2025). Extensive Cholesteatoma Compromising the Entire Ipsilateral Skull Base: Excision Through a Multi-Corridor Surgical Technique. Reports, 8(3), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030148