Possible Coexistence of Pellagra in a Malnourished Patient with Seizure and Multiple Cerebrovascular Foci: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Report

2.1. Clinical Presentations

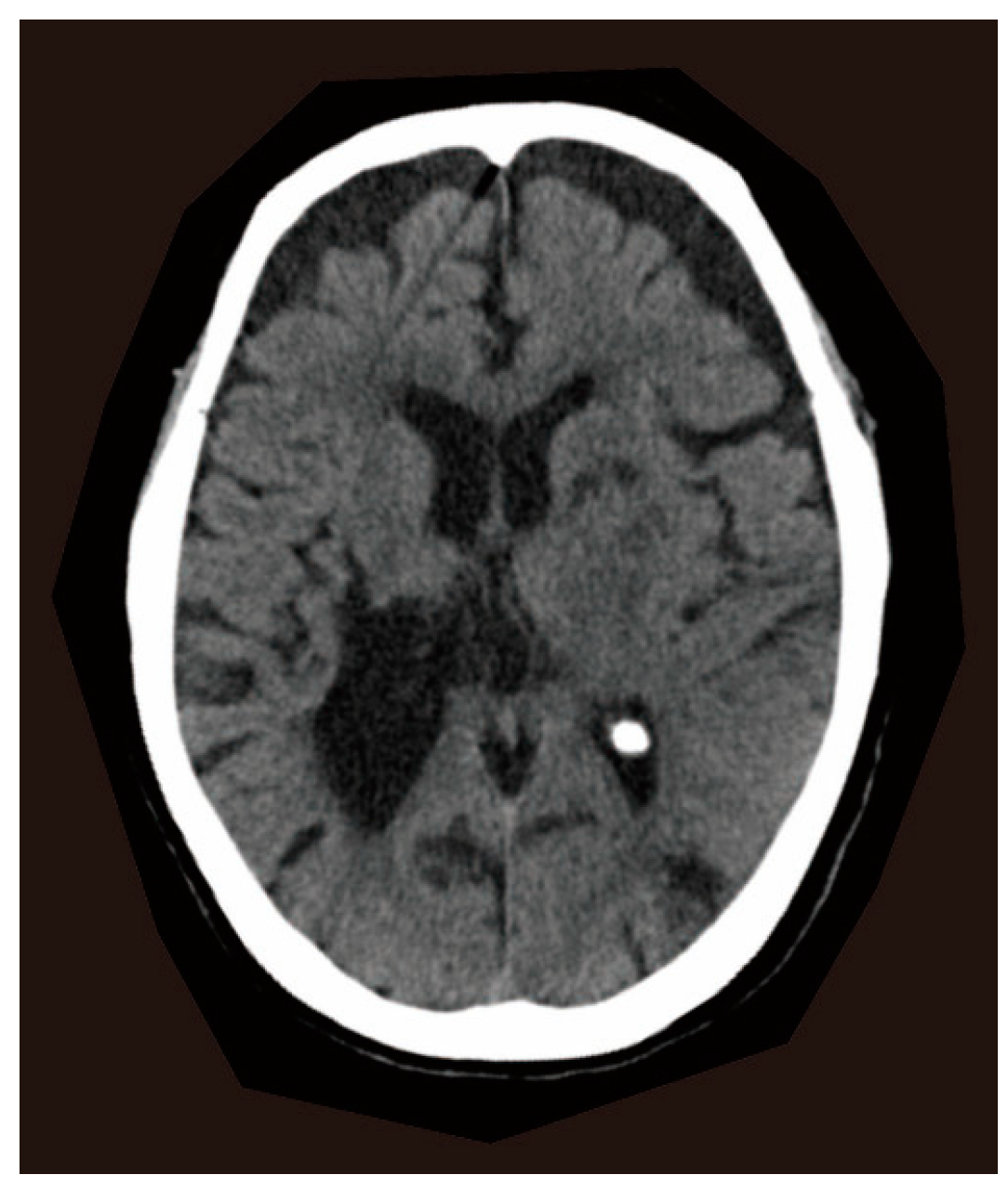

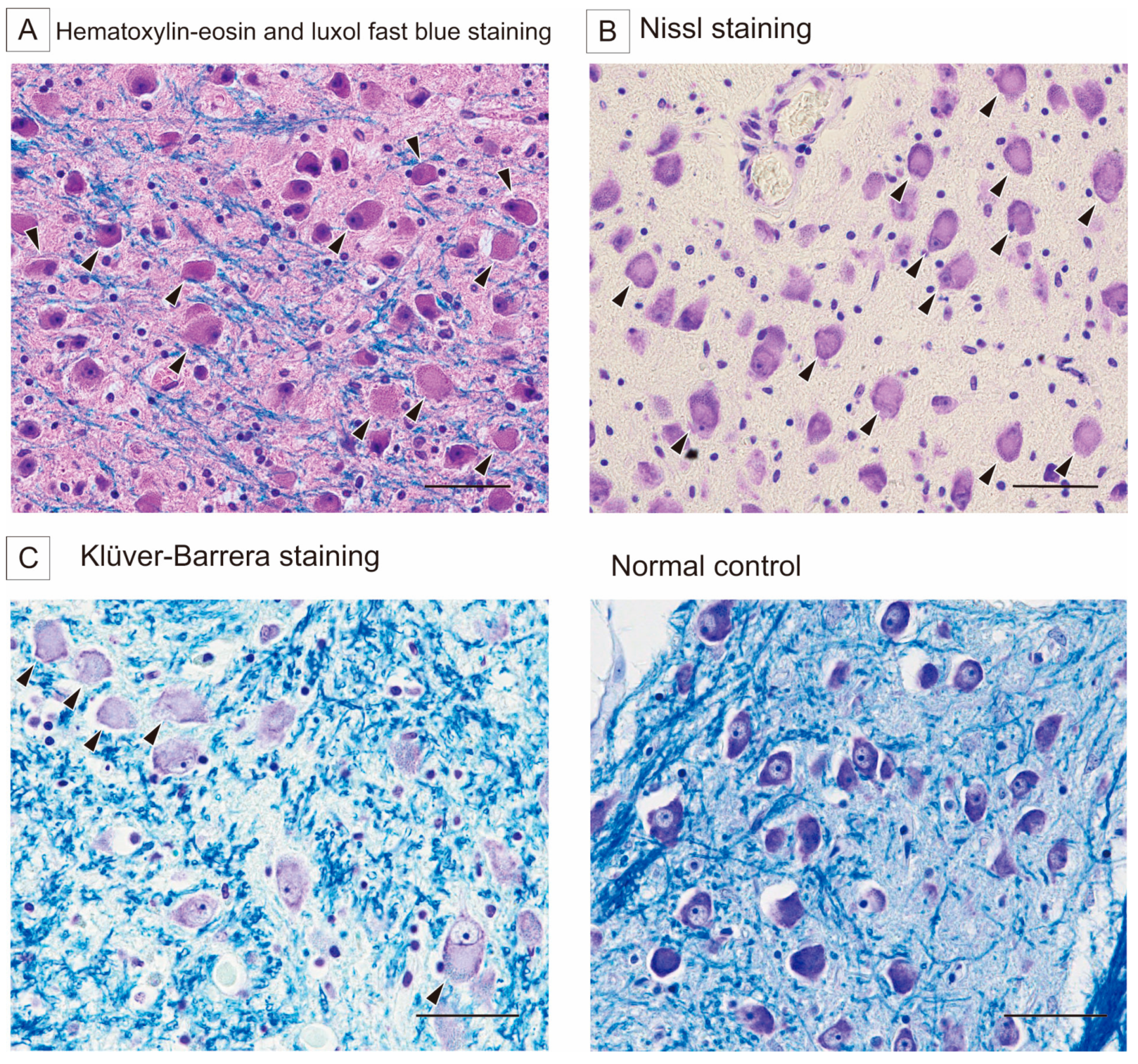

2.2. Autopsy Findings

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hegyi, J.; Schwartz, R.A.; Hegyi, V. Pellagra: Dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004, 43, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, K.; Thappa, D.M. Pellagra and skin. Int. J. Dermatol. 2002, 41, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piqué-Duran, E.; Pérez-Cejudo, J.A.; Cameselle, D.; Palacios-Llopis, S.; García-Vázquez, O. Pellagra: A Clinical, Histopathological, and Epidemiological Study of 7 Cases. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2012, 103, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, E.; Anyim, O.; Thomas, N.; Umezurike, O. Pellagra: A Possible Dermatological Complication of HIV Infection: A Case Report. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2020, 10, 823–825. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, A.B.; Emmanuel, P.; Manchan, D.B.; Onimis, O.E.; Yakubu, M.; Hirayama, K. Pellagra, a re-emerging disease: A case report of a girl from a community ravaged by insurgency. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onteeru, M. Pellagra as a potential complication of anorexia nervosa: A comprehensive literature review. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 32, 200197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanaraj, J.; Khaliq, W.; Kotwal, S. Pellagra: An. Unusual Cause for Altered Mental Status. Cureus 2024, 16, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanna, A.E.; Williams, A.C. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in an Early Description of Pellagra. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 22, 451.e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanna, A.E.; Mitchell, J.W.; Williams, A.C. The neuropsychiatry of pellagra in early American studies. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 25, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Man, X.; Wang, W.; Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Du, Y.; Cong, L. A case of alcoholic pellagra presenting with dementia and polyneuropathy. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 43, 739–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthe, S.K.; Sato, R. Alcoholic Pellagra as a Cause of Altered Mental Status in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 53, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengistu, S.B.; Ali, I.; Alemu, H.; Melese, E.B. Case report: Pellagra presentation with dermatitis and dysphagia. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1390180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonathan, E. Pellagra/Anorexia Nervosa Case Report Pellagra May Be a Rare Secondary Complication of Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Altern. Med. Rev. 2003, 8, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimha, V.L.; Ganesh, S.; Reddy, S.; Shukla, L.; Mukherjee, D.; Kandasamy, A.; Chand, P.K.; Benegal, V.; Murthy, P. Pellagra and alcohol dependence syndrome: Findings from a tertiary care addiction treatment centre in India. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019, 54, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, N.; Nishihara, Y. Pellagra among chronic alcoholics: Clinical and pathological study of 20 necropsy cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1981, 44, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.; Neff, M. Recognising the return of nutritional deficiencies: A modern pellagra puzzle. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 11, e227454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Na, D.L.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.J.; Myung, H.J.; Kim, M.K.; Chi, J.G. Alcoholic pellagra encephalopathy combined with Wernicke disease. J. Korean Med. Sci. 1991, 6, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikawa, H.; Suzuki, K. Lesions in the skin, intestine, and central nervous system induced by an antimetabolite of niacin. Am. J. Pathol. 1986, 122, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reimund, E. Sleep deprivation-induced neuronal damage may be due to nicotinic acid depletion. Med. Hypotheses 1991, 34, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krassner, M.M.; Kauffman, J.; Sowa, A.; Cialowicz, K.; Walsh, S.; Farrell, K.; Crary, J.F.; McKenzie, A.T. Postmortem changes in brain cell structure: A review. Free Neuropathol. 2023, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aoki, H.; Uchihara, T.; Ito, Y. Possible Coexistence of Pellagra in a Malnourished Patient with Seizure and Multiple Cerebrovascular Foci: A Case Report. Reports 2025, 8, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020062

Aoki H, Uchihara T, Ito Y. Possible Coexistence of Pellagra in a Malnourished Patient with Seizure and Multiple Cerebrovascular Foci: A Case Report. Reports. 2025; 8(2):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020062

Chicago/Turabian StyleAoki, Hanako, Toshiki Uchihara, and Yoshinori Ito. 2025. "Possible Coexistence of Pellagra in a Malnourished Patient with Seizure and Multiple Cerebrovascular Foci: A Case Report" Reports 8, no. 2: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020062

APA StyleAoki, H., Uchihara, T., & Ito, Y. (2025). Possible Coexistence of Pellagra in a Malnourished Patient with Seizure and Multiple Cerebrovascular Foci: A Case Report. Reports, 8(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8020062