Abstract

Intestinal-failure-associated liver disease (IFALD) is a common complication of prolonged parenteral nutrition (PN). Risk factors for IFALD include clinical features, as well as medical interventions, and its management was initially based on the decrease or interruption of parenteral nutrition while increasing enteral nutrition. However, the tolerance of full enteral nutrition in children with intestinal failure may require prolonged intestinal rehabilitation over a period of years. As a consequence, infants unable to wean from PN are prone to develop end-stage liver disease. We describe the case of an infant receiving long-term PN who was diagnosed with IFALD wherein we were able to reverse IFALD by switching lipid emulsions to fish oil monotherapy. A systemic review of case reports and case series on reversing IFALD using fish oil lipid emulsion follows the case description.

1. Introduction

Intestinal failure (IF) in infants and children, caused by insufficient bowel length or function, is a devastating condition that can be broadly defined as the inability of the gastrointestinal tract to sustain life without supplemental parenteral nutrition (PN). Parenteral nutrition is a lifesaving therapy for these children, but long-term PN treatment is limited by serious complications, including blood-stream infections, mechanical catheter-associated complications (breakage or thrombosis), metabolic bone disease, metabolic abnormalities, and others. The hepatobiliary consequences of PN include cholestasis, liver inflammation, and fibrosis, which leads to cirrhosis, portal hypertension, end-stage liver disease, and death [1,2].

Up to 75% of infants who require PN for 60 days or more develop intestinal-failure-associated liver disease (IFALD) [1,2]. Up to 26% of these patients will end up with a liver transplant and 27% will eventually die [2].

The risk factors for IFALD include clinical features such as premature birth, low birth weight, gastrointestinal mucosal disease, and recurrent bacterial sepsis, as well as medical interventions, such as long-term use of PN, absence or delayed introduction of enteral feeds, prolonged diverting enterostomies, and multiple operative procedures [2,3,4].

In recent years, it was demonstrated that the composition and timing of enteral feeding can affect the achievement of enteral autonomy. Prompt initiation of enteral feeding after bowel resection has been reported to improve the rate of enteral autonomy. For infants with short-bowel syndrome, human milk is considered most suitable for enteral feeding, because it contains growth factors, amino acids, immunoglobulins, and other immunologically important compounds that may promote intestinal adaptation. When human milk is unavailable, amino acid-based formulas are commonly used [3,4].

The management of children with IFALD was initially based on the decrease or the interruption of parenteral nutrition while increasing enteral nutrition. However, tolerance of full enteral nutrition in children with intestinal failure may require prolonged intestinal rehabilitation over a period of years [3]. As a consequence, infants unable to wean from PN are prone to develop end-stage liver disease [4].

Intravenous lipid emulsions (IVLEs) are indispensable components of PN as a non-carbohydrate source of energy. Soybean-oil-based lipid emulsions (LE) have been widely used for several decades and are still used as the major components in the current lipid formulations. For example, Intralipid® 20% contains 100% soybean oil and the more recent SMOFlipid 20% is a mixture of 30% soybean oil, 30% medium-chain TGs, 25% olive oil, and 15% fish oil. Studies have demonstrated a clear association between IVLEs and PN-associated liver disease. The mechanism for this remains unclear; however, both animal and human research mostly implicates phytosterols and ω-6 (n6) fatty acids [5,6,7,8,9].

In contrast, fish-oil-based lipid emulsions (FOLEs) have been shown to be associated with full resolution of IFALD [10,11,12,13,14,15]. The beneficial effects of FOLE have been attributed to the high proportion of ω-3 fatty acids, which, in contrast to ω-6 fatty acids, have been shown to possess considerable anti-inflammatory properties [16,17,18,19].

We describe the case of an infant receiving long-term PN who was diagnosed with IFALD wherein we were able to reverse IFALD by switching from SMOF to fish oil monotherapy. A systemic review of case reports and case series of reverse IFALD using FOLEs follows the case description.

2. Case Report

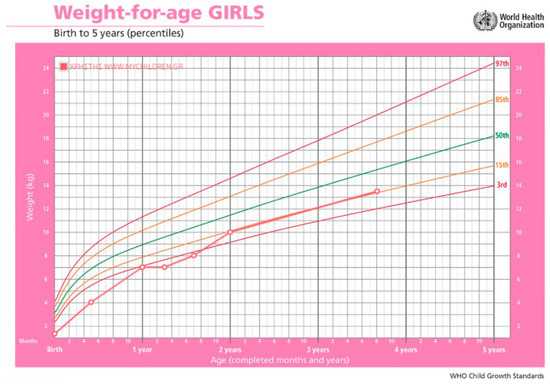

A girl born prematurely, at 29 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 1300 g, was diagnosed on day 9 with necrotizing enterocolitis. A laparotomy was performed and extensive bowel necrosis was found, involving nearly the whole small bowel. Massive small bowel resection was performed with only the duodenum and 15 cm of the small intestine spared. Her general condition improved but she still could not tolerate oral feeding. Cholestasis with progressively increasing bilirubin levels was noted at 3 weeks after initiation of TPN.

The patient was transferred to our unit at the age of 5 months. Oral feeding was started and was gradually increased, until the patient could cover 30% of her total calory needs, with respective decrease in the amount of PN injected. However, cholestasis showed no improvement and the patient begun showing signs of biliary cirrhosis, hypersplenism, and coagulopathy. A liver biopsy could not be performed due to coagulopathy so liver ultrasound and elastography were used to determine the severity of liver damage. At that time, the patient had a liver stiffness result equal to 8 kPa (F2 fibrosis—moderate). Table 1 summarizes the laboratory results from the day she was admitted to our hospital, Figure 1 and Figure 2 demonstrate the bilirubin and transaminase levels’ evolution, and Figure 3 shows the patient’s growth chart.

Table 1.

Serum liver function tests and coagulation studies.

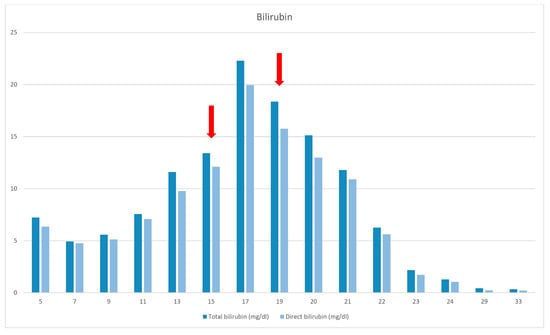

Figure 1.

Bilirubin levels. The red arrows (1st) indicates the sepsis episode and the introduction of FOLE (2nd).

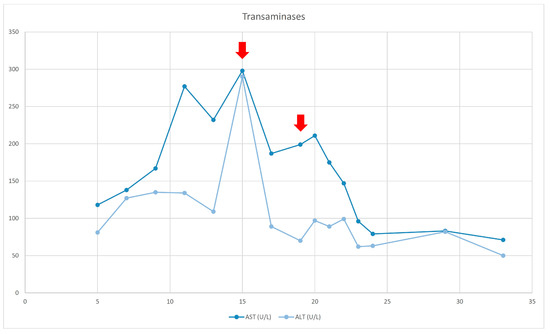

Figure 2.

Transaminases evolution. The red arrows (1st) indicates the sepsis episode and the introduction of FOLE (2nd).

Figure 3.

Patient’s growth chart. The green line represents the 50th percentile for weight according to age. The orange lines represent the 15th percentile and the red lines the 97th percentile.

At the age of 15 months, the patient’s course was complicated because of catheter-related sepsis and multiorgan failure. Bilirubin rose up to 19, 94 mg/dl, liver elastography was 10 kPa (F3 fibrosis—severe), and liver transplantation was discussed. SMOF infusion was decreased with no improvement. The replacement of LE by FOLE did not happen until the child was 19 months old (due to difficulties to getting access to them), with a starting dose of 0.5 g/kg/d for 2 weeks, followed by 1 g/kg/d.

At the age of 21 months jaundice was improved and TB/DB levels finally normalized at 24 months of age. FOLE monotherapy was maintained for 8 months. SMOF was then reintroduced and maintained as a combination of 30% FOLE and 70% SMOF lipids.

The patient is now 3.5 years old and still dependent on PN. Liver function is fully preserved and we have not seen any relapse of cholestasis.

3. Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, PubMed Central, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect up to 31 December 2021, combining the keywords intestinal-failure-associated liver disease; parenteral-nutrition-associated liver disease; parenteral nutrition lipid formulations; and fish-oil-based lipid emulsions. We further searched the reference lists of identified articles for additional papers. We included case reports or case series of pediatric patients. We restricted results to English language published papers and this could be considered as a limitation of the study.

4. Discussion

Over the last few decades, the approach for children with liver disease due to intestinal failure has evolved and this fact led to a decrease in cases of end-stage liver disease requiring liver transplantation. One of the most important things that led to this change is the different approach to the use of lipids in parenteral nutrition, either by reducing the amount used or by using alternative sources of lipids, with fish oil lipid emulsions proving to be the most important development in parenteral nutrition.

The mechanisms by which lipid emulsions participate in IFALD development are not fully understood. There is strong evidence that the long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs) within the soy-based lipid emulsions play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of IFALD [5,6,7,8,9]. The most important LCPUFAs are ω-6FA and ω-3FA, that have common metabolic pathways. They interact with each other through a negative feedback pathway by competing for nutrient substrate availability and for the same metabolic enzymes for membrane synthesis and integration. A crucial factor in the reduction in inflammatory response is the ω-6FA to ω-3FA ratio (n6:n3 ratio). It is known that active ω-3FAs interfere with the metabolization of the ω-6 fatty Acids (FA) arachidonic acid, leading to a downregulation of inflammatory eicosanoids [6]. In order to act as an immunomodulator the optimal ratio of n6:n3 is thought to be between 1:1 and 4:1 [9].

Over the last decades, soy-based lipid emulsions (Intralipid) have been the cornerstone of PN, and contain predominantly ω-6FAs with a n6:n3 ratio of 5.5:1. Intralipid contains ω-3FAs in the form of a-linolenic acid, and not in the biologically active form of docosahexanoic and eicosapentaenoic acid, and thus does not provide a substantial and utilizable source of ω-3FAs to the infant, because infants have a limited capacity to metabolize a-linolenic acid. Furthermore, the predominant ω-6FAs have been implicated in the development of hepatic steatosis, which is one of the early hallmarks of IFALD.

PN solutions, which are composed of ω-3FAs in addition to ω-6FAs (SMOFlipid 20%), have several beneficial effects concerning the prevention and treatment of IFALD. Additionally, it has recently been shown that the use of fish-oil-based lipid emulsions could reverse hepatic steatosis in both PN and non-PN models of hepatic steatosis. The administration of ω-3FA through several mechanisms, such as a reduction in phytosterols dose, by eicosanoid-mediated mechanisms and by modifying biliary canalicular membrane, could affect bile flow. Moreover, the addition of ω-3FA, through the reduction in ω-6FA, leads to a change in the profile of eicosanoids from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory. This shift in inflammatory mediators may have an important role in the progression of hepatitis and the resultant fibrosis in response to the initial cholestatic and steatotic insult [5,6,7,8,9].

FOLE monotherapy was first described by Gura et al. in 2002 [12], in a PN-dependent, soy-allergic adolescent who developed severe essential fatty acid deficiency after a period of fat-free PN administration. Since 2004, fish oil IVLE monotherapy has been prescribed to treat patients with IFALD.

We report the reversal of IFALD observed in a child receiving long-term PN by replacing SMOF with FOLE. This reversal was seen during the period of FOLE treatment, while the patient remained PN-dependent and despite the fact that she had factors predisposing to the failure of FOLE therapy.

Several clinical studies have previously described the reversal of cholestasis in PN-dependent infants with IFALD after changing lipid emulsion to FOLE. In most reports, infants developed IFALD due to soybean oil (Intralipid) administration [10,11,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. In only two cases, as in our case, IFALD developed while receiving SMOF as a lipid source [35,36] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of case reports and case series identified by systemic literature review, with the case reports of patients that were on SMOF before the initiation of FOLE in bold.

In the case we describe, the infant progressed to severe liver disease despite low-dose IVLE (SMOF 1 gr/kg/d) and PN cycling. Switching LE to FOLE was decided upon as a rescue therapy and a bridge to liver transplantation. Based on previous publications and the published literature, fish-based IVLE was initiated at 0.5 g/kg/d and was gradually increased to a maximum of 1 g/kg/d [10,11,15].

Previously published case reports mention that the median time for resolution of IFALD varies from 40 days to 8 months [11,23,24,25,26,27,29,31,34]. More specifically, one of the first cases reported was that of an infant who received fish-oil-based IVLE after developing cholestasis and IFALD. The authors documented the resolution of IFALD after 8 months of therapy [25]. FOLE was also used in a retrospective cohort of 12 children diagnosed with short bowel syndrome (SBS) and advanced IFALD. In that cohort, FOLE was associated with liver function restoration within a median of 24 (range 15.3–55.3) weeks [26]. In another paper describing two infants who received FOLE, the authors reported that, regardless of the enteral nutrition regimen, there was a complete resolution of hyperbilirubinemia and cholestasis within 8 weeks of the initiation of FOLE [11]. Our patient had a complete resolution after 20 weeks of fish-oil-based IVFE therapy, without any side effect. Liver transplantation is therefore no longer a plan.

More importantly, our patient had poor prognostic factors, such as low birth weight, advanced age at fish-oil initiation, severe liver disease, and other comorbidities, such as renal disease. FOLE initiation reversed IFALD in 5 months and the child remains asymptomatic after one year of single SMOF-LE use.

Nandivada P et al. reviewed the data of patients treated with FOLE at Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, from 2004 to 2014, and whose cholestasis failed to reverse despite fish oil ILE monotherapy, in order to identify the factors associated with the failure of fish oil therapy in treating IFALD and to guide referral guidelines [38]. The authors noted that, among the 182 patients treated with fish oil ILE, 86% achieved cholestasis resolution and 14% failed therapy. The patients who failed therapy had a lower birth weight and were older at FOLE initiation (20.4 weeks [9.9, 38.6 weeks]) compared to those whose cholestasis resolved (11.7 weeks [7.3, 21.4 weeks]). Moreover, the patients who failed therapy had more advanced liver disease at FOLE initiation, as evidenced by a higher direct bilirubin (10.4 mg/dL [7.5, 14.1 mg/dL] vs. 4.4 mg/dL [3.1, 6.6 mg/dL]).

We decided to proceed with a combination of SMOF-FOLE infusion in order to benefit from the effects of fish oil while reducing the risk of essential fatty lipid deprivation. Furthermore, a published review of the long-term outcomes of patients with IFALD that biochemically resolved under FOLE, and who resumed exclusive soybean oil LE, concludes that they were at high risk of IFALD relapse [34].

5. Conclusions

Without question, the most effective treatment for IFALD is to maximize enteral nutrition while decreasing PN. However, a significant number of patients are unable to tolerate enteral feeding at the moment needed. Fish-oil-based lipid emulsion has promise in treating IFALD, but there are limited data regarding its use in children, especially as monotherapy. There is a need for further randomized control trials to formulate a standardized protocol for the administration of such emulsions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: S.F. and I.K., methodology: S.F. and I.K., Investigation: A.K., N.Z., S.Z., N.K. and E.S.; Data curation: A.K. and I.K., Writing—original draft: A.K. and I.K.; Writing—review and editing: I.K. and S.F., Supervision: I.K. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval is not required according to the Ethics Committee of Attikon University General Hospital, for retrospective information drawn from a patient’s record.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The clinical data of this case report are available in the patient’s medical record. Due to personal data protection rules, data cannot be published.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Squires, R.H.; Duggan, C.; Teitelbaum, D.H.; Wales, P.W.; Balint, J.; Venick, R.; Rhee, S.; Sudan, D.; Mercer, D.; Martinez, J.A.; et al. Natural History of Pediatric Intestinal Failure: Initial Report from the Pediatric Intestinal Failure Consortium. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 723–728.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, C.P.; Jaksic, T. Pediatric Intestinal Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infantino, B.J.; Mercer, D.F.; Hobson, B.D.; Fischer, R.T.; Gerhardt, B.K.; Grant, W.J.; Langnas, A.N.; Quiros-Tejeira, R.E. Successful Rehabilitation in Pediatric Ultrashort Small Bowel Syndrome. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; McCowen, K.C.; Bistrian, B.R.; Thibault, A.; Keane-Ellison, M.; Forse, R.; Babineau, T.; Burke, P. Incidence, prognosis, and etiology of end-stage liver disease in patients receiving home total parenteral nutrition. Surgery 1999, 126, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.A.; A Taylor, O.; Prendergast, D.R.; Zimmerman, T.L.; Von Furstenberg, R.; Moore, D.D.; Karpen, S.J. Stigmasterol, a Soy Lipid–Derived Phytosterol, Is an Antagonist of the Bile Acid Nuclear Receptor FXR. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 62, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, P.T.; Whitfield, P.; Iyer, K. The Role of Phytosterols in the Pathogenesis of Liver Complications of Pediatric Parenteral Nutrition. Nutrition 1998, 14, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, P.J.; Greene, A.K.; Garza, J.; Gura, K.; Alwayn, I.P.; Voss, S.; Nose, V.; Satchi-Fainaro, R.; Zausche, B.; Mulkern, R.V.; et al. The route of lipid administration affects parenteral nutrition–induced hepatic steatosis in a mouse model. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2005, 40, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares, W.; Dhaliwal, R.; PharmD, B.J.; Stapleton, R.D.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N.; Heyland, D.K. Parenteral fish oil lipid emulsions in the critically ill: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2014, 38, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisel, J.A.; Le, H.D.; de Meijer, V.E.; Nose, V.; Gura, K.M.; Mulkern, R.V.; Sharif, M.R.A.; Puder, M. Comparison of 5 intravenous lipid emulsions and their effects on hepatic steatosis in a murine model. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Meijer, V.E.; Gura, K.M.; Meisel, J.A.; Le, H.D.; Puder, M. Parenteral fish oil monotherapy in the management of patients with parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gura, K.M.; Duggan, C.P.; Collier, S.B.; Jennings, R.W.; Folkman, J.; Bistrian, B.R.; Puder, M. Reversal of Parenteral Nutrition–Associated Liver Disease in Two Infants with Short Bowel Syndrome Using Parenteral Fish Oil: Implications for Future Management. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e197–e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gura, K.M.; Parsons, S.K.; Bechard, L.J.; Henderson, T.; Dorsey, M.; Phipatanakul, W.; Duggan, C.; Puder, M.; Lenders, C. Use of a fish oil-based lipid emulsion to treat essential fatty acid deficiency in a soy allergic patient receiving parenteral nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 24, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, H.D.; De Meijer, V.E.; Zurakowski, D.; Meisel, J.A.; PharmD, K.M.G.; Puder, M. Parenteral fish oil as monotherapy improves lipid profiles in children with parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2010, 34, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premkumar, M.H.; Carter, B.A.; Hawthorne, K.M.; King, K.; Abrams, S.A. High Rates of Resolution of Cholestasis in Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Disease with Fish Oil-Based Lipid Emulsion Monotherapy. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 793–798.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puder, M.; Valim, C.; Meisel, J.A.; Le, H.D.; de Meijer, V.E.; Robinson, E.M.; Zhou, J.; Duggan, C.; Gura, K.M. Parenteral Fish Oil Improves Outcomes in Patients with Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Injury. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicken, B.J.; Huynh, H.Q.; Turner, J.M. More evidence on the use of parenteral omega-3 lipids in pediatric intestinal failure. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, E.M.; Le, H.D.; Mark, P. Prevention of parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease: Role of omega-3 fish oil. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2010, 15, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.E.; Babcock, T.A.; Jho, D.H.; Helton, W.S.; Espat, N.J. NF-kappa B inhibition by omega-3 fatty acids modulates LPS-stimulated macrophage TNF-alpha transcription. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003, 284, L84–L89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, W.; Li, N.; Li, J. Omega-3 fatty acids-supplemented parenteral nutrition decreases hyperinflammatory response and attenuates systemic disease sequelae in severe acute pancreatitis: A randomized and controlled study. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2008, 32, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Valim, C.; Johnston, P.; Le, H.; Meisel, J.; Arsenault, D.A.; Gura, K.M.; Puder, M. Impact of Fish Oil-Based Lipid Emulsion on Serum Triglyceride, Bilirubin, and Albumin Levels in Children with Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Disease. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 66, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, K.L.; Dunn, J.C.Y.; Shew, S.B.; Reyen, L.; Farmer, D.G.; Devaskar, S.U.; Venick, R.S. Pediatric Intestinal Failure–Associated Liver Disease Is Reversed with 6 Months of Intravenous Fish Oil. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 38, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandivada, P.; Chang, M.I.M.; Potemkin, A.K.B.; Carlson, S.J.M.; Cowan, E.; O’Loughlin, A.A.M.; Mitchell, P.D.M.; Gura, K.M.P.D.; Puder, M. The Natural History of Cirrhosis From Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Disease after Resolution of Cholestasis with Parenteral Fish Oil Therapy. Ann. Surg. 2015, 261, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekema, G.; Falchetti, D.; Boroni, G.; Tanca, A.R.; Altana, C.; Righetti, L.; Ridella, M.; Gambarotti, M.; Berchich, L. Reversal of severe parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease in an infant with short bowel syndrome using parenteral fish oil (Omega-3 fatty acids). J. Pediatr. Surg. 2008, 43, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, I.R.; Sterescu, A.; Pencharz, P.B.; Kim, J.H.; Wales, P.W. Changing the Paradigm: Omegaven for the Treatment of Liver Failure in Pediatric Short Bowel Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2009, 48, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gura, K.M.; Lee, S.; Valim, C.; Zhou, J.; Kim, S.; Modi, B.P.; Arsenault, D.A.; Strijbosch, R.A.M.; Lopes, S.; Duggan, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Fish-Oil–Based Fat Emulsion in the Treatment of Parenteral Nutrition–Associated Liver Disease. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e678–e686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, M.D.; Scaife, E.R.; Jackson, W.D.; Meyers, R.L.; Mulroy, C.W.; Book, L.S. Elimination of Soybean Lipid Emulsion in Parenteral Nutrition and Supplementation with Enteral Fish Oil Improve Cholestasis in Infants with Short Bowel Syndrome. Nutr. Clin. Pr. 2010, 25, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.H.Y.; Wong, K.K.Y.; Wong, R.M.S.; Tsoi, N.S.; Chan, K.L.; Tam, P.K.H. Clinical Experience in Managing Pediatric Patients with Ultra-short Bowel Syndrome using Omega-3 Fatty Acid. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 20, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, A.M.; Altamimi, E.; Clause, R.-F.; Saab, J.; Mileski, H.; Cameron, B.; Fitzgerald, P.; Sant’Anna, G.M. Implementation of a multidisciplinary team approach and fish oil emulsion administration in the management of infants with short bowel syndrome and parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, M.H.; Carter, B.A.; Hawthorne, K.M.; King, K.; Abrams, S.A. Fish Oil–Based Lipid Emulsions in the Treatment of Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Disease: An Ongoing Positive Experience. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2014, 5, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, B.J.; Reddix, B.A.; Wolk, R.A. Improvement in Parenteral Nutrition–Associated Cholestasis with the Use of Omegaven in an Infant with Short Bowel Syndrome. Nutr. Clin. Pr. 2016, 31, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belza, C.; Thompson, R.; Somers, G.R.; de Silva, N.; Fitzgerald, K.; Steinberg, K.; Courtney-Martin, G.; Wales, P.W.; Avitzur, Y. Persistence of hepatic fibrosis in pediatric intestinal failure patients treated with intravenous fish oil lipid emulsion. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 52, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrell, M.; Moreira, A.; Green, K.; Jacob, R.; Tragus, R.; Keller, L.; Quinn, A.; McCurnin, D.; Gong, A.; El Sakka, A.; et al. Favorable Outcomes of Preterm Infants with Parenteral Nutrition–associated Liver Disease Treated with Intravenous Fish Oil–based Lipid Emulsion. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, N.; Yan, W.; Lu, L.; Tao, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Cai, W. Effect of a fish oil-based lipid emulsion on intestinal failure-associated liver disease in children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Venick, R.S.; Shew, S.B.; Dunn, J.C.Y.; Reyen, L.; Gou, R.; Calkins, K.L. Long-Term Outcomes in Children with Intestinal Failure–Associated Liver Disease Treated with 6 Months of Intravenous Fish Oil Followed by Resumption of Intravenous Soybean Oil. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2018, 43, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, H.J.; Yoon, J.; Hong, S.H.; Oh, C.-Y.; Lee, S.-K.; Seo, J.-M. Reversal of Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease by Switching From a Combination Lipid Emulsion Containing Fish Oil to Fish Oil Monotherapy. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2016, 40, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Sung, S.I.; Park, H.J.; Chang, Y.S.; Park, W.S.; Seo, J.-M. Fish Oil Monotherapy for Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease on SMOFlipid in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Meijer, V.E.; Gura, K.M.; Le, H.D.; Meisel, J.A.; Puder, M. Fish Oil–Based Lipid Emulsions Prevent and Reverse Parenteral Nutrition–Associated Liver Disease: The Boston Experience. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2009, 33, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandivada, P.; Baker, M.A.; Mitchell, P.D.; A O’loughlin, A.; Potemkin, A.K.; Anez-Bustillos, L.; Carlson, S.J.; Dao, D.T.; Fell, G.L.; Gura, K.M.; et al. Predictors of failure of fish-oil therapy for intestinal failure–associated liver disease in children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gura, K.M.; Premkumar, M.H.; Calkins, K.L.; Puder, M. Fish Oil Emulsion Reduces Liver Injury and Liver Transplantation in Children with Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease: A Multicenter Integrated Study. J. Pediatr. 2020, 230, 46–54.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).