TB Presenting as Recurrent Pneumonia in a HIV-Infected Infant in Central Viet Nam

Abstract

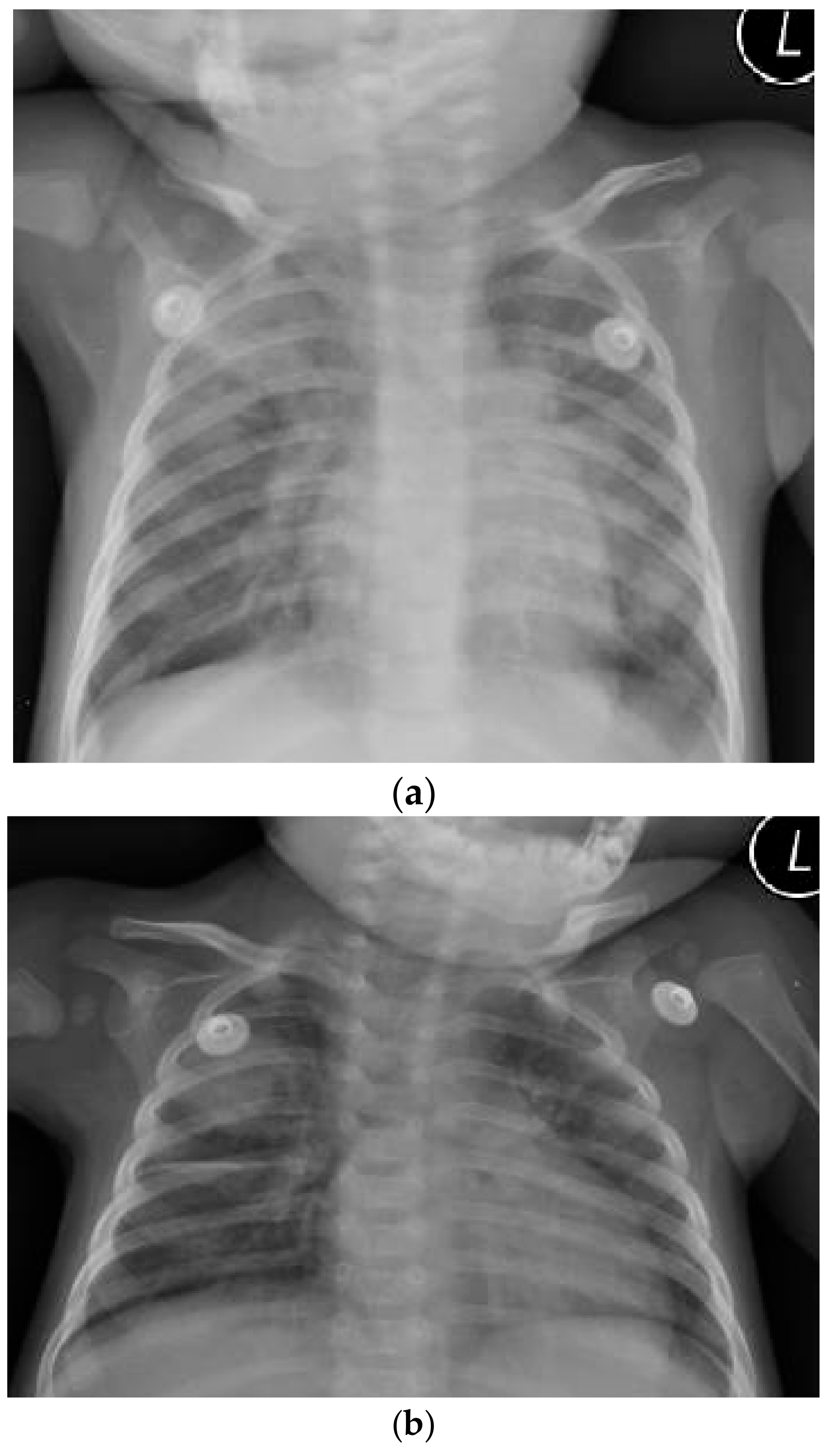

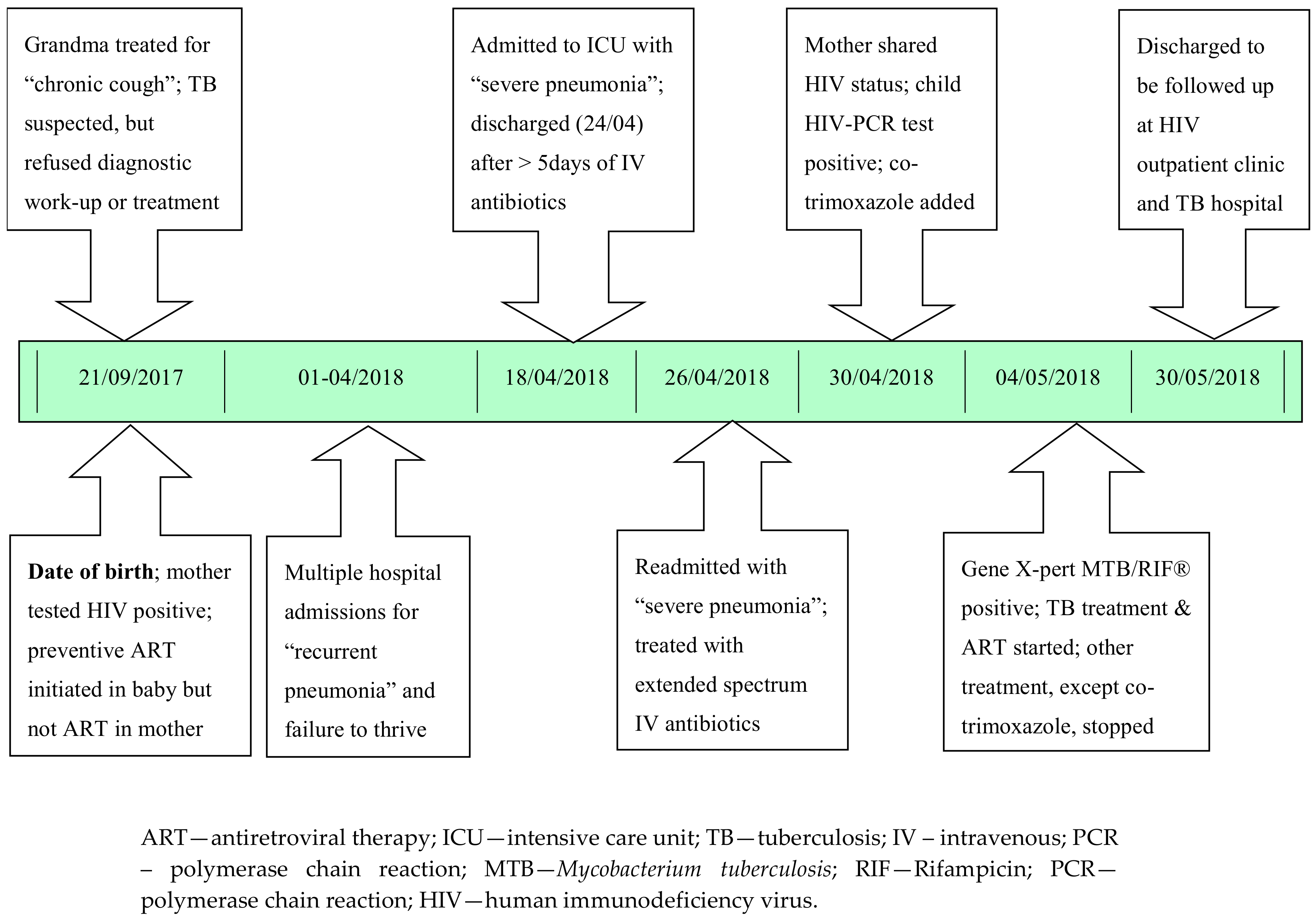

1. Case Report

2. Additional Medical History (Retrospectively Obtained)

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marais, B.J.; Schaaf, H.S. Childhood tuberculosis: An emerging and previously neglected problem. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 24, 727–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marais, B.; Graham, S.; Cotton, M.; Beyers, N. Diagnostic and management challenges for childhood tuberculosis in the era of HIV. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196 (Suppl. 1), S76–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, Q.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, V.; Nguyen, T.; Sintchenko, V.; Marais, B. Tuberculosis and HIV co-infection—Focus on the Asia-Pacific region. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 32, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishnu, B.; Bhaduri, S.; Kumar, A.M.; Click, E.S.; Chadha, V.K.; Satyanarayana, S.; Nair, S.A.; Gupta, D.; Ahmed, Q.T.; Sarkar, S.; et al. What are the reasons for poor uptake of HIV testing among patients with TB in an Eastern India District? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, C.A.; Marais, B.J.; Abrams, E.J. HIV: Prevention of mother-to-child transmission. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2011, 2011, 0909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marais, B.J.; Gupta, A.; Starke, J.R.; El Sony, A. Tuberculosis in women and children. Lancet 2010, 375, 2057–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bhosale, R.; Kinikar, A.; Gupte, N.; Bharadwaj, R.; Kagal, A.; Joshi, S.; Khandekar, M.; Karmarkar, A.; Kulkarni, V.; et al. Maternal tuberculosis: A risk factor for mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenthani, L.; Haas, A.D.; Tweya, H.; Jahn, A.; van Oosterhout, J.J.; Chimbwandira, F.; Chirwa, Z.; Ng’ambi, W.; Bakali, A.; Phiri, S.; et al. Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (“Option B+”) in Malawi. AIDS 2014, 28, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdts, S.E.; Wagenaar, B.H.; Micek, M.A.; Farquhar, C.; Kariaganis, M.; Amos, J.; Gimbel, S.; Pfeiffer, J.; Gloyd, S.; Sherr, K. Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy by HIV testing service type in Central Mozambique: A retrospective cohort study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 66, e37–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violari, A.; Cotton, M.F.; Gibb, D.M.; Babiker, A.G.; Steyn, J.; Madhi, S.A.; Jean-Philippe, P.; McIntyre, J.A. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 2233–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach: World Health Organization; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, B.J.; Gie, R.P.; Schaaf, H.S.; Hesseling, A.C.; Obihara, C.C.; Starke, J.J.; Enarson, D.A.; Donald, P.R.; Beyers, N. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: A critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era [State of the Art]. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2004, 8, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Triasih, R.; Robertson, C.F.; Duke, T.; Graham, S.M. A prospective evaluation of the symptom-based screening approach to the management of children who are contacts of tuberculosis cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 60, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marais, B.J.; Ayles, H.; Graham, S.M.; Godfrey-Faussett, P. Screening and preventive therapy for tuberculosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2009, 30, 827–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, E.J.; Bond, V.A.; Marais, B.J.; Godfrey-Faussett, P.; Ayles, H.M.; Beyers, N. High levels of vulnerability and anticipated stigma reduce the impetus for tuberculosis diagnosis in Cape Town, South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 28, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.T.K.; Nguyen, N.V.; Phung, T.D.; Marais, B. X-pert MTB/RIF® Diagnosis of Twin Infants with Tuberculosis in Da Nang, Viet Nam. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaaf, H.S.; Collins, A.; Bekker, A.; Davies, P. Tuberculosis at extremes of age. Respirology 2010, 15, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Velez, C.M.; Roya-Pabon, C.L.; Marais, B.J. A systematic approach to diagnosing intra-thoracic tuberculosis in children. J. Infect. 2017, 74 (Suppl. 1), S74–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, L.M.; Jeena, P.M.; Gajee, K.; Thula, S.A.; Sturm, A.W.; Cassol, S.; Tomkins, A.M.; Coovadia, H.M.; Goldblatt, D. Effect of age, polymicrobial disease, and maternal HIV status on treatment response and cause of severe pneumonia in South African children: A prospective descriptive study. Lancet 2007, 369, 1440–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliwa, J.N.; Karumbi, J.M.; Marais, B.J.; Madhi, S.A.; Graham, S.M. Tuberculosis as a cause or comorbidity of childhood pneumonia in tuberculosis-endemic areas: A systematic review. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.N.; Ha, D.T.M.; Nhan, H.T.; Wolbers, M.; Nhu, N.T.Q.; Heemskerk, D.; Quang, N.D.; Phuong, D.T.; Hang, P.T.; Loc, T.H.; et al. Prospective evaluation of GeneXpert for the diagnosis of HIV-negative pediatric TB cases. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Boulware, D.R.; Callens, S.; Pahwa, S. Pediatric HIV immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2008, 3, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B-Lajoie, M.R.; Drouin, O.; Bartlett, G.; Nguyen, Q.; Low, A.; Gavriilidis, G.; Easterbrook, P.; Muhe, L. Incidence and prevalence of opportunistic and other infections and the impact of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected children in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesheim, S.R.; Kapogiannis, B.G.; Soe, M.M.; Sullivan, K.M.; Abrams, E.; Farley, J.; Palumbo, P.; Koenig, L.J.; Bulterys, M. Trends in opportunistic infections in the pre–and post–highly active antiretroviral therapy eras among HIV-infected children in the Perinatal AIDS Collaborative Transmission Study, 1986–2004. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesseling, A.; Cotton, M.; Fordham von Reyn, C.; Graham, S.; Gie, R.; Hussey, G. Consensus statement on the revised World Health Organization recommendations for BCG vaccination in HIV-infected infants: Submitted on behalf of the BCG Working Group, Child Lung Health Section, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 38th Union World Conference on Lung Health, Cape Town, 8–12 November 2007 [Official statement]. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2008, 12, 1376–1379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hesseling, A.C.; Marais, B.J.; Gie, R.P.; Schaaf, H.S.; Fine, P.E.; Godfrey-Faussett, P.; Beyers, N. The risk of disseminated Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) disease in HIV-infected children. Vaccine 2007, 25, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesseling, A.C.; Rabie, H.; Marais, B.J.; Manders, M.; Lips, M.; Schaaf, H.S.; Gie, R.P.; Cotton, M.F.; Van Helden, P.D.; Warren, R.M.; et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine—Induced disease in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofenson, L.M.; Brady, M.T.; Danner, S.P.; Dominguez, K.L.; Hazra, R.; Handelsman, E.; Havens, P.; Nesheim, S.; Read, J.S.; Serchuck, L.; et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children: Recommendations from the National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013, 32, i-KK4. [Google Scholar]

- Tarwa, C.; De Villiers, F. The use of the Road to Health Card in monitoring child health. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2007, 49, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, P.; Nguyen, S.; Nguyen, T.; Marais, B. TB Presenting as Recurrent Pneumonia in a HIV-Infected Infant in Central Viet Nam. Reports 2018, 1, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports1020012

Nguyen P, Nguyen S, Nguyen T, Marais B. TB Presenting as Recurrent Pneumonia in a HIV-Infected Infant in Central Viet Nam. Reports. 2018; 1(2):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports1020012

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Phuong, Son Nguyen, Thinh Nguyen, and Ben Marais. 2018. "TB Presenting as Recurrent Pneumonia in a HIV-Infected Infant in Central Viet Nam" Reports 1, no. 2: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports1020012

APA StyleNguyen, P., Nguyen, S., Nguyen, T., & Marais, B. (2018). TB Presenting as Recurrent Pneumonia in a HIV-Infected Infant in Central Viet Nam. Reports, 1(2), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports1020012