1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, wildfires in the United States have increased in size, frequency, and intensity, presenting growing challenges for fire management and suppression efforts. Research indicates that the “most extreme fires are also larger, more common, and are more likely to co-occur with other extreme fires”, further exacerbating the difficulty of wildfire suppression [

1]. This trend is projected to worsen, with future wildfire seasons expected to be longer and characterized by more frequent and severe fire events [

2].

As wildfires continue to grow in scale, suppression efforts have increasingly relied on aviation support, including aerial retardant drops and water scooping operations. These aerial suppression efforts come with high costs—monetary, environmental, and human. Between 2007 and 2011, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) spent approximately

$323 million annually on aviation-based suppression efforts [

3]. This expenditure increased in the following decade, with aviation costs averaging

$493 million per year between 2011 and 2020, accounting for approximately 30% of the total USFS wildfire suppression expenditures [

4]. These high suppression costs often divert funding away from proactive fire prevention strategies, such as prescribed burns, forest thinning, and community resilience programs—measures that are generally more cost-effective and reduce long-term risk [

5].

Beyond financial costs, aerial suppression also has significant personnel-related consequences and potential environmental impacts. From 2011 through 2020, aviation-related accidents accounted for the highest percentage of federal firefighter fatalities, including both contract and employee personnel, representing 30% of all fatalities during that period [

4]. Furthermore, the use of fire retardant has introduced substantial amounts of toxic metals into ecosystems. It is estimated that from 2009 to 2021, aerial suppression operations contributed approximately 380,000 kg of toxic metals to the environment [

6].

In addition to these high costs and risks, it must be considered that aviation resources are also limited, with a finite number of aircraft and personnel available. Given these challenges, it is critical to assess the effectiveness of aerial suppression efforts. Understanding when and where aviation resources have the most impact can help optimize their use, ensuring that they provide maximum benefit while minimizing unnecessary expenditures, environmental degradation, and personnel hazards. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of aviation in wildfire suppression and identify conditions under which it has the greatest operational value.

Considering the critical importance of assessing the effectiveness of aerial firefighting, researchers have employed various approaches to achieve this goal. In his review of wildfire suppression effectiveness research, Plucinski [

7] explores the research completed prior to 2016. He notes that previous studies have been conducted at multiple scales, ranging from flame-scale experiments to fireline and fire incident-scale analyses. Flame-scale studies, examining areas less than 10 m in length, have typically focused on retardant effectiveness in terms of flame length or intensity. These experiments are easier to design and control, allowing researchers to isolate specific factors influencing suppression outcomes. At the fireline scale (approximately 10–1000 m in length), researchers have investigated suppression effects along sections of the fire perimeter to evaluate resource productivity and the impact of tactics on fire behavior in the field. Fire studies at the incident-scale, which refers to the entirety of the burned area, have further expanded insight into aerial support effectiveness by analyzing broader suppression efforts, including initial attack containment success.

Due to the nature of the data available for this study, our research focuses on fireline and fire incident scales. At these scales, controlled experiments are challenging to conduct, necessitating reliance on observational studies. Therefore, careful study design is necessary to account for confounding variables and ensure meaningful conclusions. Researchers have proposed various methodological approaches to improve the reliability of suppression effectiveness assessments. One approach to examining suppression effects on fire behavior is by comparing fire behavior along suppressed sections of the fire perimeter to unsuppressed sections, provided that comparable conditions—such as fuel, terrain, and weather—can be established [

7].

In their paper, Plucinski and Pastor [

8] state that to attribute fire behavior changes to suppression efforts, it is preferable to account for other influencing variables such as aircraft flight and delivery system conditions, vegetation and fuel characteristics, weather and terrain conditions, fire behavior metrics, and concurrent ground suppression activities. Although many of these variables undoubtedly influence fire behavior in reality, they may not contribute meaningfully to improving analysis or predictive performance in a modeling context. Additionally, even with all these factors considered, fully attributing suppression effectiveness to aerial efforts remains challenging. Therefore, we should aim to collect as many variables as possible and prioritize those that are most relevant for improving our analysis.

Many prior fire suppression studies have relied on in situ data collection, where researchers gather detailed information about individual fire incidents. This approach allows for a more detailed analysis but often limits the number of cases that can be examined, making it difficult to draw broad conclusions about suppression effectiveness. Despite these limitations, several studies have leveraged in situ data to evaluate fire suppression tactics.

The U.S. Forest Service attempted to expand the available data by completing the Aerial Firefighting Use and Effectiveness (AFUE) [

9] study which provided empirical data on the effectiveness of aerial suppression efforts. From 2015 to 2018, AFUE personnel collected data across all nine Forest Service regions, documenting drop objectives and outcomes, aircraft types, fire characteristics, and ground resource involvement. While the AFUE report summarized statistics on the performance of drops, it did not analyze the conditions under which those drops were most effective, limiting its utility in determining optimal deployment strategies.

Katuwal et al. [

10] aimed to provide broad recommendations on when different fire suppression tactics, including aviation, might be most effective by using stochastic frontier analysis to evaluate the efficiency of various tactics. The study assessed factors contributing to the maximization of controlled fireline length. Analyzing daily perimeters from 63 fires, the study examined the impact of crews, dozers, engines, helicopters, and air tankers. The results indicated that air resources (helicopters and air tankers) did not significantly contribute to controlled fireline length. On the other hand, the authors noted that the study could not account for the specific mission objectives of these aircraft, which may have aimed to slow fire progression rather than halt it entirely. This limitation underscores the challenge of evaluating suppression effectiveness when specific operational goals are unknown.

In a study out of Ontario, Wheatley et al. [

11] considered wildfires that received aviation support and modeled initial attack (IA) success using logistic regression with supervised forward-selection of variables. IA success was defined as a fire being contained by 1:00 PM on the second day of attack. This analysis identified factors associated with containment success. While volume of retardant dropped and the number of airtankers used were negatively associated with suppression success (likely due to more challenging fires receiving greater resources), other key predicting variables included fire size at IA initiation, weather conditions, fire behavior, fuel type, and fire cause. The study suggested that redirecting IA air resources toward fires with their model’s highest containment probability could improve suppression efficiency.

While in situ data has been invaluable, recent advancements in remote sensing have enabled researchers to analyze suppression effectiveness at broader scales, reducing data collection costs and increasing the number of incidents studied. The next couple of studies have leveraged remotely sensed data to further refine suppression assessments, offering insights that were previously difficult to obtain with ground-based observations alone.

Stonesifer et al. [

12] analyzed historical large airtanker drop data from the 2010–2012 fire seasons across the United States by geospatially intersecting drop locations with operational and environmental factors. Consistent with previous research, results indicate that aviation resources are predominantly deployed on fires that are more difficult to contain. Airtankers were generally used according to operational guidelines, including appropriate altitude and speed. However, findings suggest that drops sometimes occurred under conditions where flame lengths exceeded recommended thresholds. The study also highlights the influence of human proximity on drop locations and reveals that aviation resources were utilized during extended attack operations more frequently than previously recognized.

In his PhD dissertation for Colorado State University, Bryan [

13] employed a difference-in-differences estimation and a regression discontinuity design to compare fire behavior in treated versus untreated areas. His findings suggest that large air tankers effectively diminish flame intensity, reduce wildfire spread likelihood, and delay fire growth. He also found that aerial retardant drops were most effective in grass and shrub fuel types and when used in conjunction with other suppression efforts. Furthermore, Bryan’s research introduced a cost-effectiveness metric that considers avoided damages along with providing a framework for evaluating the trade-offs between the usage of aerial and ground firefighting resources.

The next step in suppression research is the development of strategic, risk-informed decision support frameworks that integrate insights from both in situ and remotely sensed studies. Some of these frameworks already exist, such as the Aviation Use Summary (AUS), which was reviewed in Stonesifer et al. [

4]. The AUS leverages aircraft event tracking data, geospatial information and analytical tools to evaluate aircraft use at the incident level, helping guide risk based decision making.

The ultimate goal of this study is to develop a predictive model that can help determine the conditions under which an aerial retardant drop may reduce the rate of spread (ROS) of a wildfire. Identifying these conditions would improve strategic deployment of aviation resources, optimizing their impact while mitigating unnecessary costs and risks. Our research aligns with earlier studies by utilizing topographical, weather, fuel, and fire behavior variables to inform aerial suppression decision-making frameworks. While only a few recent studies have capitalized on the availability of remotely sensed data, our approach aims to build upon this foundation. Our research is innovative because it has access to extensive new aviation data, will calculate the ROS using progressive 12-h perimeters, and will use ROS to evaluate the effectiveness of aerial interventions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we describe the data sources, preprocessing steps, and modeling framework used to evaluate the effectiveness of aerial retardant drops in reducing wildfire ROS. This includes our approach for calculating ROS, generating synthetic drops, and building predictive models.

Section 3 presents the performance of the models we developed to assess the impact of aerial suppression on ROS reduction. In

Section 4, we interpret these findings in the context of wildfire suppression effectiveness, highlight key limitations of our approach, and compare our results to those of prior studies. Finally, in

Section 5, we outline directions for future research and the potential implications of our findings for operational fire management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

To evaluate the effectiveness of aerial retardant drops, we assembled a comprehensive dataset integrating multiple sources of fire behavior and suppression data. Data were collected in support of our effort to distinguish predictable fire behavior from the fire’s response to retardant. First, we obtained access to a dataset collected by the U.S. Forest Service detailing large airtanker drop locations and characteristics across the United States. This dataset provided critical information on drop timing, location, and operational parameters. Additionally, our lab had previously compiled a dataset containing topographical, fuel, and weather information for wildfires in Oregon, allowing us to analyze environmental factors influencing suppression outcomes. To further assess the impact of aerial suppression on fire behavior, we calculated ROS by acquiring progressive 12-h fire perimeter data accessed through NASA’s Earthdata portal.

The dataset detailing large airtanker drops was collected across the United States by both federally owned and contracted airtankers. Drop events were recorded using Additional Telemetry Unit (ATU) sensors, which automatically logged the location of door openings and closings associated with retardant releases. In addition to drop locations, ATUs captured key flight and delivery parameters, including airspeed, altitude, heading, and the volume of retardant delivered. These door event data points allowed for the creation of precise drop line representations within a geographic information system (GIS). While ATU data collection is fully automated, the dataset we used had been previously refined by Stonesifer. She had removed false positives, manually linked drop events to specific wildfire incidents, and flagged potential non-fire drops. It contained data for approximately 7500 drops spanning the nation from 2016 through 2021.

Prior to this study, our lab had compiled a comprehensive dataset encompassing environmental variables for fire-affected regions. This dataset was created by extracting topographical, weather, and fuel characteristics for points within wildfires in Oregon. The wildfires were identified using the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity (MTBS) fire perimeters dataset from 2016 to 2020. The MTBS program is an interagency initiative aimed at consistently mapping the burn severity and extent of large fires (greater than 1000 acres in the western United States) [

14]. This dataset provided critical contextual information for understanding the conditions under which aerial suppression efforts were deployed. The specific variables included in this dataset, along with their sources and spatial resolutions, are detailed in

Table 1.

To track fire progression and quantify ROS, we used fire perimeter data generated by the Fire Events Data Suite (FEDS) algorithm, accessed through NASA’s Earthdata portal. The FEDS algorithm processes thermal observations from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) sensors aboard the Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 satellites to delineate fire perimeters. With twice-daily overpasses, VIIRS provides updated fire perimeter data every 12 h, offering a detailed view of fire evolution over time [

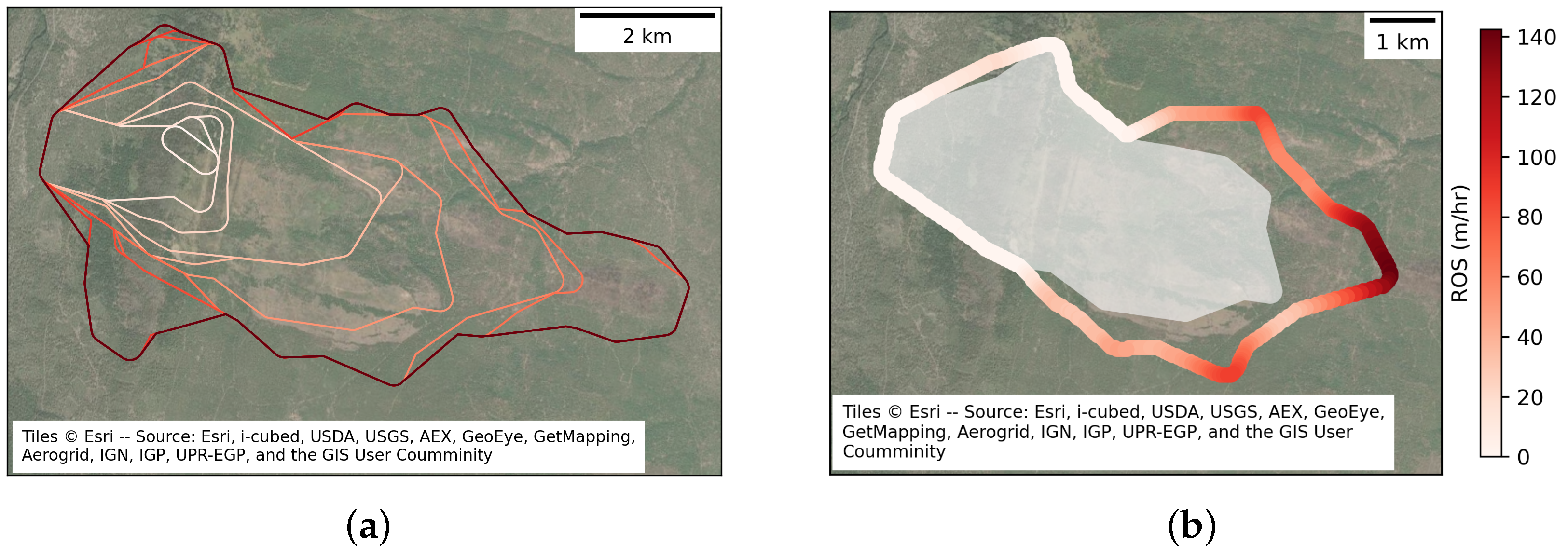

22]. We calculated the ROS by rasterizing each fire perimeter at a 30-m resolution and sequentially dilating the perimeter until it intersects the subsequent perimeter. The number of dilations required to reach each pixel in the subsequent perimeter was multiplied by 30 m and divided by the time difference in hours between observations, yielding a ROS (m/h) for each point along all perimeters, excluding the first. As an illustrative example,

Figure 1a shows the progression of 12-h fire perimeters for the Green Ridge Fire (August 2020, Oregon), and

Figure 1b shows the resulting ROS values calculated along the eighth perimeter of that fire.

2.2. Data Processing

To integrate the three datasets (the drops, the features, and the VIIRS perimeters), we first limited our analysis data within Oregon between 2018 and 2020 for which all required data sources were available. We resolved differences in naming conventions among the datasets by identifying matching fire events and drops based on location and timing. We then associated each aritanker drop with the corresponding environmental and fire behavior data. Environmental variables were extracted from the precompiled feature dataset (

Table 1) by buffering each drop location by 20 m and averaging the values of all intersecting raster cells.

We then quantified fire behavior before and after each airtanker drop using ROS derived from VIIRS fire perimeters delineated at a 12-h temporal resolution. For each drop, we identified the fire perimeter immediately preceding and following the drop based on time. For each point along the drop line, we located the closest points on these perimeters and averaged the ROS from those locations. These ROS values therefore represent the 12-h spread rate from one perimeter to the next. If a drop occurred after the final recorded perimeter, we assigned a post-drop ROS of zero. We excluded drops where both pre- and post-drop ROS were zero, as these cases were unlikely to provide meaningful information on suppression effectiveness. Finally, we quantified the change in ROS by subtracting the pre-drop ROS from the post-drop ROS, where negative values indicate a reduction in fire spread following the drop. The final dataset includes 586 drops associated with 31 fires.

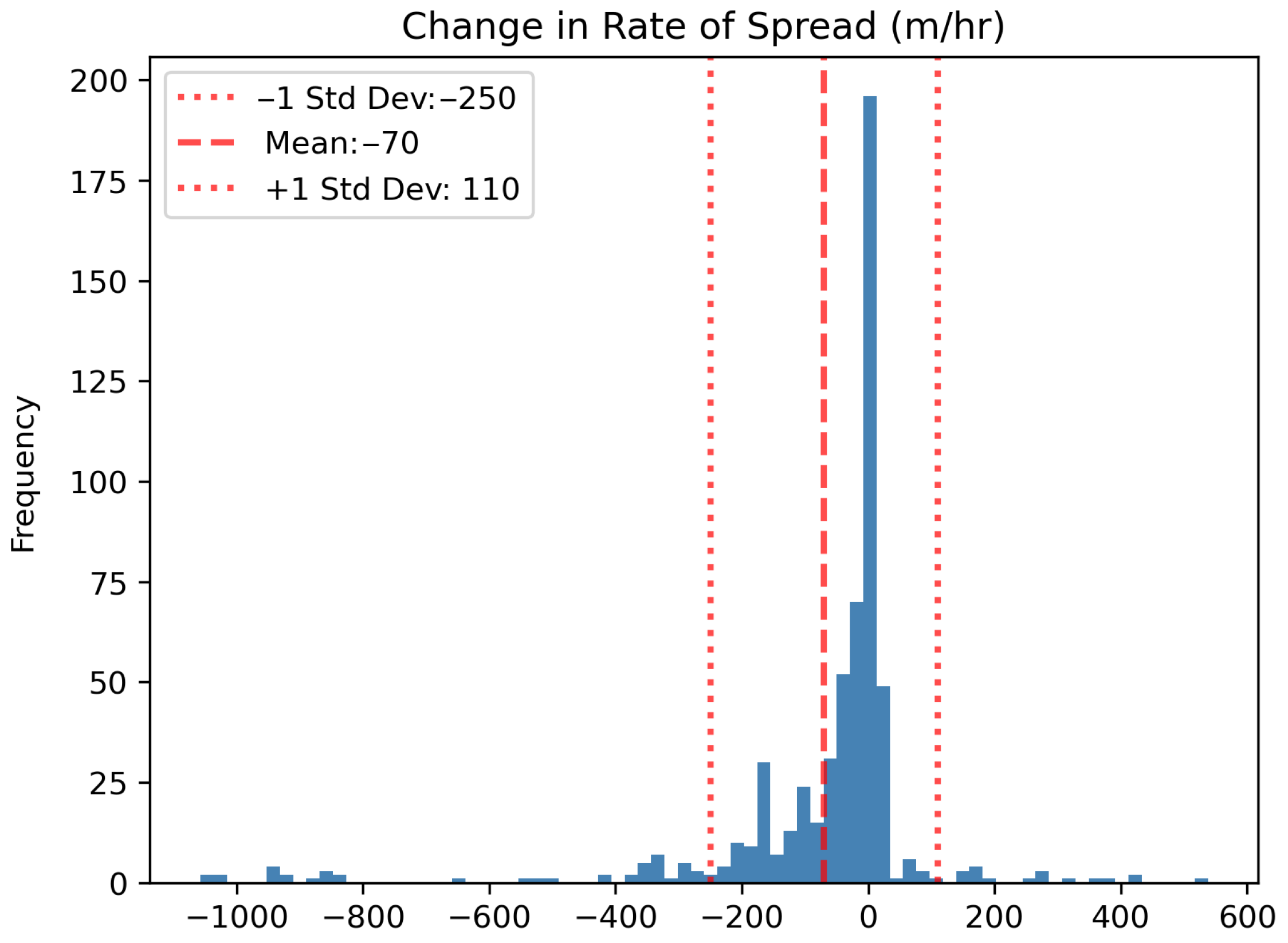

We began our analysis by examining the overall distribution of ROS changes for all recorded drops. To visualize this, we present a histogram of the change in ROS in

Figure 2. The average change in ROS across all drops was

m/h, indicating a general reduction in fire spread following aerial suppression. However, a significant number of drops resulted in little to no change in ROS. Given this, we established a threshold to identify drops that effectively slowed fire spread. Specifically, we consider only those drops where ROS decreased by at least 70 m/h as successful in slowing fire progression. We refer to cases having less than this threshold of change of ROS as persisting.

Next, we compared the distributions of the environmental variables for drops that effectively slowed the ROS to those where the ROS persisted. Our analysis revealed notable differences in several variables, including temperature difference and elevation. As can be seen in

Figure 3a,b, these variables exhibited distinct distributions between the two groups as can be seen in the means and standard deviation. This suggested that they may serve as important predictors in explaining variation in suppression outcomes. In contrast, other variables, such as the previous area of the fire and hillshade, exhibited relatively similar distributions (

Figure 3c,d). Given the potential for machine learning models to detect subtle interactions and patterns not immediately evident through visual inspection, we retained all variables in our modeling framework. The inclusion of a broader set of features allowed the models to explore complex relationships within the data.

To rigorously assess whether aerial retardant drops contribute to reductions in the ROS, it is essential to establish whether fire behavior would have remained unchanged in the absence of a drop. Without a clear comparison or counter factual case, attributing changes in ROS to suppression efforts remains speculative. We address this limitation by introducing synthetic drops that provide a baseline for expected fire behavior without aerial suppression. By comparing changes in ROS between real and synthetic drops, we can better discern whether observed reductions in ROS exceed those occurring naturally in unsuppressed areas. This approach enables us to better quantify the contribution of aerial suppression to changes in fire spread.

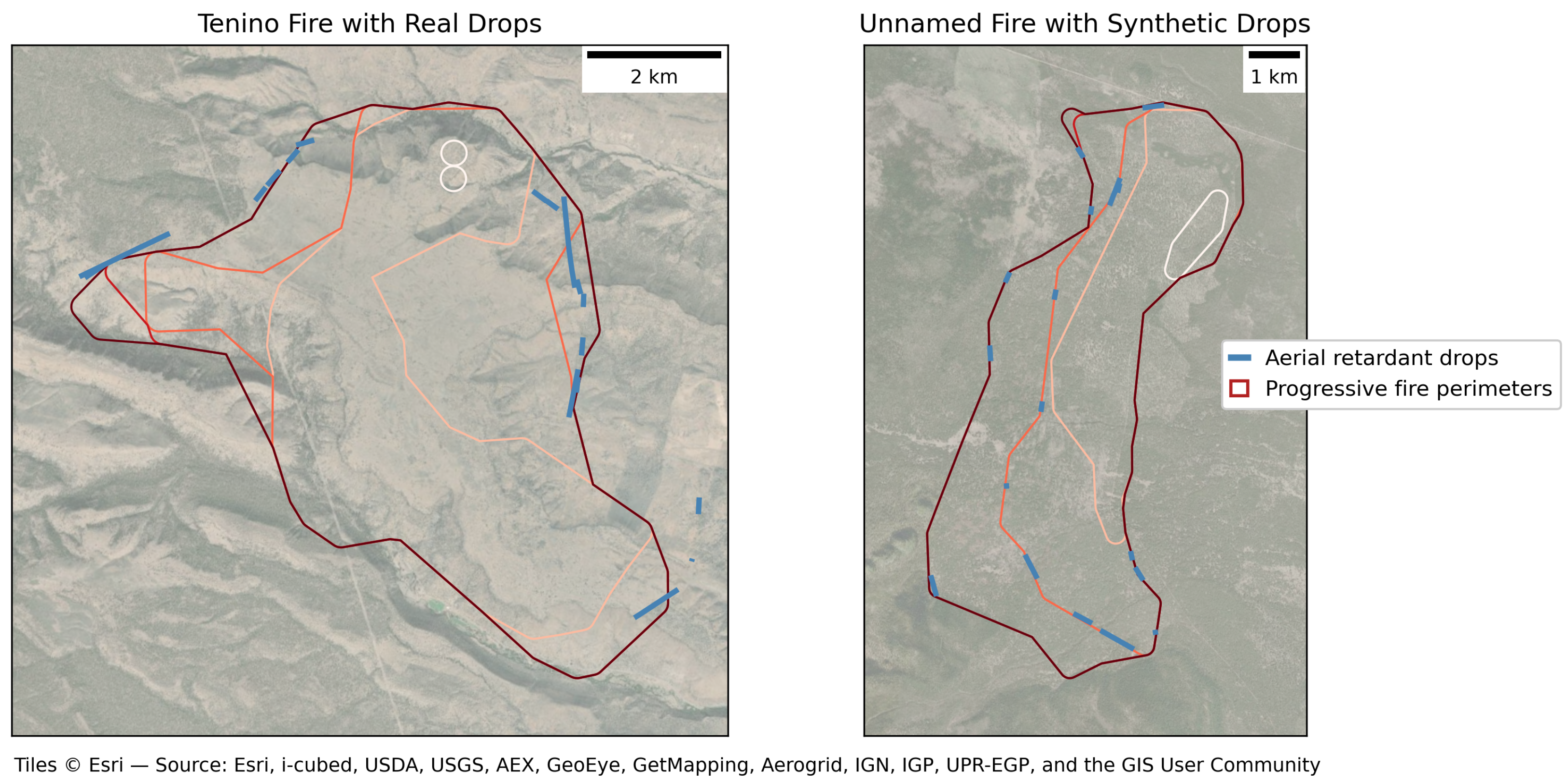

The synthetic drops were designed to mirror the temporal distribution, frequency, and spatial scale of observed drops while remaining independent of fire behavior outcomes. We first identified all fires with documented aerial retardant drops () and all fires without drops (). Fires in both groups were characterized by the number of available progressive fire perimeters, which served as a proxy for fire duration. Fires without drops were randomly subsampled and matched to fires with drops based on the number of perimeters, ensuring comparable fire lengths between fires with documented and synthetic drops.

For each fire with observed drops, we quantified the distribution of drops across its progressive perimeters. Specifically, the perimeter index on which each drop occurred was converted to a proportional fire progression metric (e.g., a drop occurring on perimeter 2 of 5 corresponds to 40% of fire progression). The number of drops occurring at each proportional perimeter position was then transferred to the matched fire without drops. For example, if a fire with five perimeters contained three drops at 40% progression and six drops at 60% progression, the matched control fire received three synthetic drops on its 40% perimeter and six synthetic drops on its 60% perimeter. An example of a fire with observed drops and its matched fire with synthetic drops is shown in

Figure 4.

Synthetic drop lengths were generated by sampling from an empirical probability distribution constructed from the lengths of observed retardant drops. For each synthetic drop, candidate lengths were restricted to values less than one-tenth of the diagonal length of the target perimeter’s bounding box to prevent unrealistically long drops relative to perimeter scale. A length was randomly selected from the constrained distribution and removed from the candidate pool to avoid reuse.

The spatial placement of synthetic drops along the fire perimeters was executed using a randomized approach subject to several constraints. Each target perimeter was buffered by a fixed distance, and a random starting point was selected within the buffered region. An endpoint was then generated at the sampled drop length distance from the starting point, with both endpoints required to fall within the buffer. Synthetic drops were explicitly prohibited from being placed in locations where both pre- and post-drop ROS values were zero, as such areas were excluded from the original set of real drops and would not provide a comparable basis for analysis. Additionally, each synthetic drop was required to intersect areas containing valid environmental and topographic covariate data to ensure consistency with subsequent feature extraction.

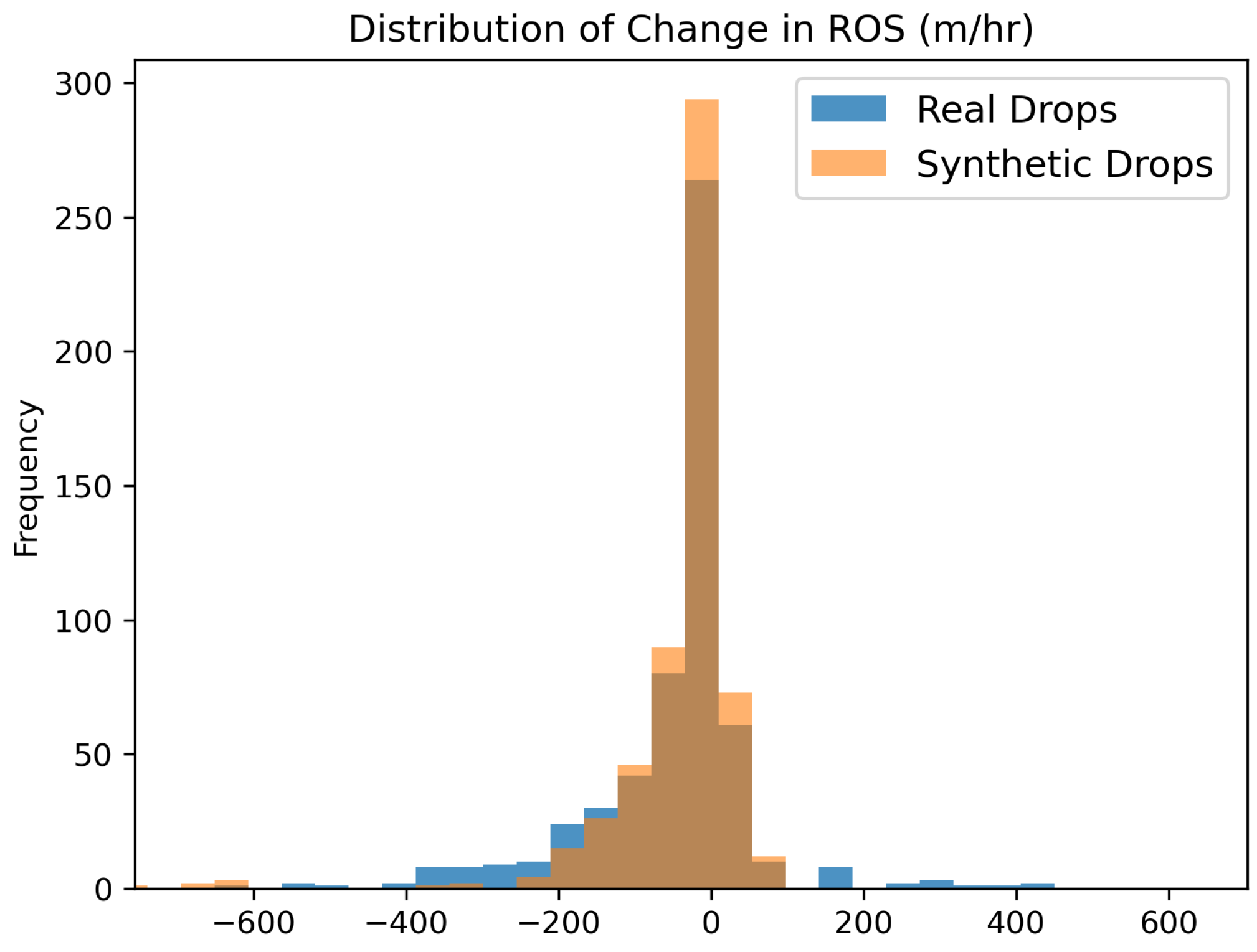

Following placement, the same feature extraction and processing workflow applied to real drops was applied to all synthetic drops. This procedure resulted in a total of 586 synthetic drops distributed across 31 fires, matching the number of real drops included in the analysis. The distribution of changes in ROS for synthetic drops closely resembled that of the real drops (

Figure 5). To formally assess this similarity, we conducted a Welch’s unequal-variance

t-test comparing changes in ROS between real and synthetic drops. The resulting

p-value (0.5046) indicated no statistically significant difference between the means, suggesting that the synthetic drops effectively captured the overall fire behavior characteristics of the observed drops.

2.3. Model Creation

To assess the effectiveness of aerial retardant drops in slowing fire spread, we developed predictive models that classified whether a drop effectively reduced the ROS. Effectively reducing ROS was measured by decreasing the ROS by at least 70 m/h between consecutive perimeters. A key component of one of our modeling approaches was incorporating both real and synthetic drops in the analysis. Specifically, we hypothesized that if the feature indicating whether a drop was real or synthetic emerged as a major predictor, it would suggest that actual retardant drops had a significant impact on ROS reduction beyond what would be expected from natural fire behavior alone.

To implement this model, which we will refer to as the full model, we utilized a random forest classifier due to its built-in feature importance metrics, robustness to non-linear relationships, and ability to handle interactions between variables. The model was trained using the environmental features from

Table 1, along with three additional predictor variables being the length of the drop, the area of the fire within the perimeter preceding the drop, and an indicator variable distinguishing real drops from synthetic ones. The target variable was a binary classification of whether or not a drop effectively slowed the ROS. To ensure a fair evaluation, we included both real and synthetic drops in the training and testing datasets. We carefully split the data so that all drops associated with a given fire were entirely within either the training or testing set, preventing data leakage and ensuring that the model was tested on independent fires it had not encountered during training.

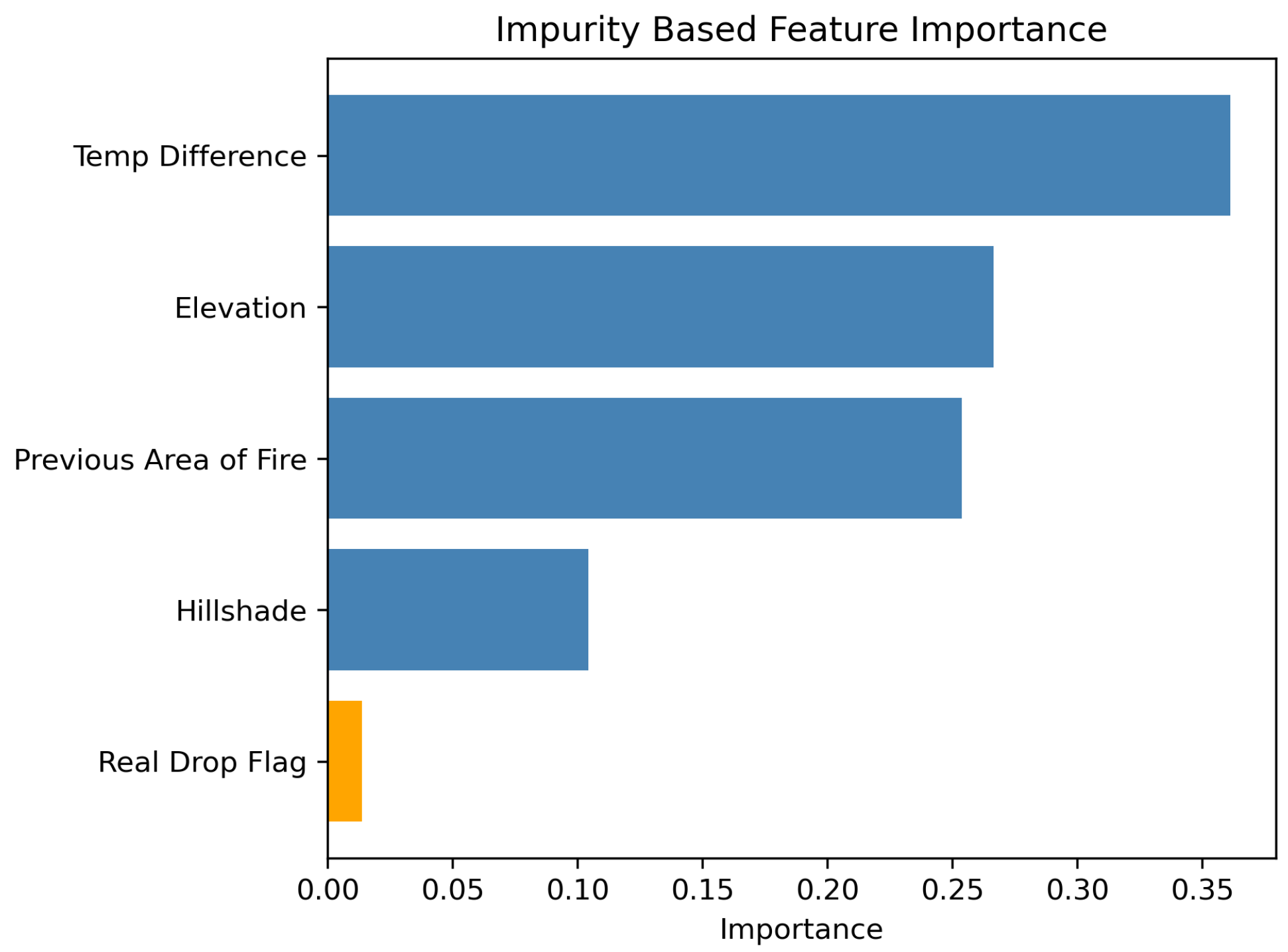

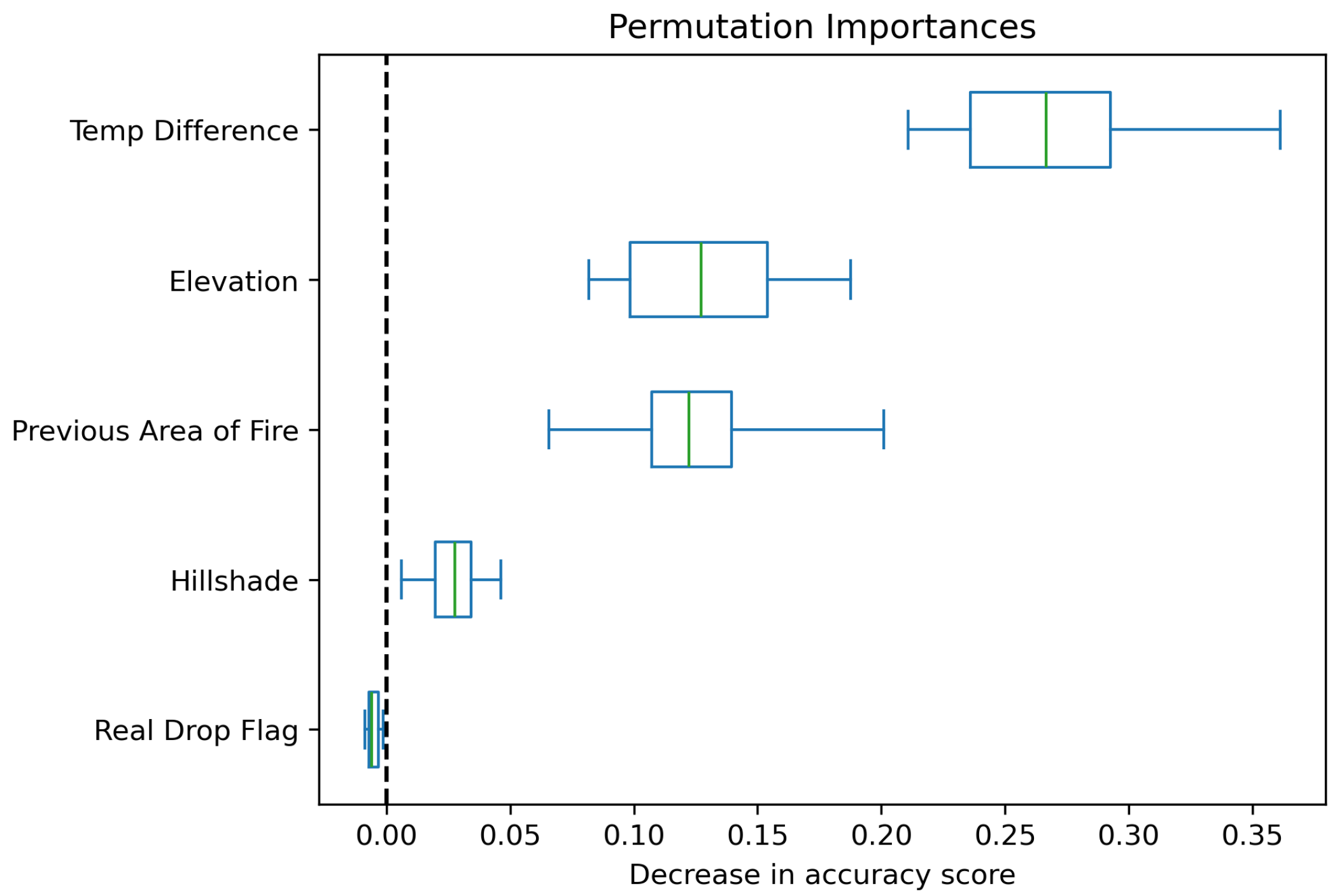

Since our primary interest was in evaluating the relative importance of the real versus synthetic drop indicator, we first trained a random forest model using all available predictors, then performed an additional feature selection step to reduce redundancy and improve interpretability. Using Spearman rank-order correlation, we quantified pairwise correlations among all predictor variables and applied hierarchical clustering with Ward’s linkage to group highly correlated features. From each cluster, we selected a representative variable based on its impurity-based feature importance in the initial model along with its distributional differences between drops with slowed and persistent ROS (

Figure 3). This process yielded a final set of four features: temperature difference, elevation, previous fire area, and hillshade. Additionally, the indicator for real versus synthetic drops was retained regardless of correlation structure, given its central role in the analysis.

As well as training the model on a mix of real and synthetic drops, we also explored an alternative approach where the model was trained exclusively on synthetic drops using all available environmental, topographic, and contextual predictor. The rationale behind this synthetic-only model was to establish a baseline that captured patterns of fire behavior in the absence of aerial suppression. We then applied the trained model to real drops to estimate where ROS would likely have persisted without aerial intervention. This allowed us to infer how frequently retardant drops were effective in slowing ROS, offering a broader perspective on suppression outcomes.

2.4. Model Sensitivity Testing

For both modeling approaches, the full and synthetic-only, we fine-tuned the hyperparameters using a grid search strategy to optimize performance. There were significantly more drops experiencing persistent ROS than those that successfully slowed it which created a large class imbalance in the target variable. Due to this imbalance, the model tended to overpredict the majority class—persistent ROS. To mitigate this, we used balanced accuracy as our scoring metric during grid search. Balanced accuracy accounts for both sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) by averaging recall across classes, making it more appropriate than standard accuracy in imbalanced classification tasks. The equation used to compute this metric is shown in Equation (

1). This approach helped us select hyperparameters that more fairly represented both classes and improved our model’s ability to more accurately classify drops.

Specifically, we tuned the number of trees in the forest, the maximum depth of each tree, the minimum number of samples required to split an internal node, the minimum number of samples required to be at a leaf node, along with class weights. The selected hyperparameters for each model are summarized in

Table 2.

We acknowledge that selecting the mean change in ROS as the threshold value (−70 m/h) to distinguish between slowed and persistent ROS is somewhat arbitrary. A change in ROS of 0 m/h may seem like an intuitive dividing line, and we tested several thresholds near zero. However, these near-zero thresholds produced models with little predictive power. This is likely because small variations in ROS, exacerbated by the approximations and uncertainties in our data and calculations, were often not meaningful. As a result, we opted to allow for some margin around this cutoff, choosing a more conservative threshold that better captured substantial reductions in fire spread.

Specifically, we evaluated a symmetric range of threshold values around the mean, varying in 0.05 standard deviation increments up to ±0.25. For both models, performance was fairly stable and consistent within ±0.1 standard deviations, with classification metrics remaining high and balanced. As thresholds deviated further, performance began to decline moderately, though it remained within an acceptable range. Even so, when we tested the median as a threshold, which is more than 0.3 standard deviations above the mean (approximately −12 m/h), performance dropped significantly. This confirmed that thresholds that were too close to zero, such as the median, reduced the model’s discriminative power by classifying many marginal changes as successful.

In addition to adjusting the threshold within a binary framework, we also explored a multiclass classification approach. Drops were grouped into classes such as slowed, constant, and persistent ROS, based on the magnitude of ROS reduction. However, the distribution of values was heavily concentrated near zero, resulting in a large number of drops being assigned to the constant category. This class imbalance led to a model that achieved high overall accuracy but poor balanced accuracy, as it predominantly predicted that all drops would fall into the majority class. Attempts to balance the class distribution reduced overall accuracy and failed to meaningfully improve performance, likely because overlapping feature patterns across classes made consistent differentiation difficult.

We also tested regression models, including both linear regression and random forest regression, to directly predict the change in ROS. Both approaches yielded low predictive power, with values below 0.1. This poor performance was again likely due to the high concentration of ROS change values near zero, limiting the model’s ability to distinguish meaningful patterns in the continuous outcome.

Taken together, these results suggest that while the mean-based threshold for the binary classification is not optimal, it lies near a local optimum in terms of model performance. Thresholds set too far from the mean, particularly in the more lenient direction, compromised predictive performance. Thresholds placed too far from zero are difficult to justify conceptually and lead to an even greater imbalance between classes, further limiting model reliability. Ultimately, the binary classification using the −70 m/h threshold offered the best balance between interpretability and model performance.

4. Discussion

Despite the strong overall performance of the model trained on both real and synthetic drops, the results do not provide strong evidence that aerial suppression efforts were a primary driver in reducing the ROS over the 12-h periods used for model evaluation. The inclusion of synthetic drops allowed us to assess whether real drops had a distinct impact beyond what would be expected from natural fire behavior. Nonetheless, the indicator variable distinguishing real from synthetic drops was among the least important predictors in the model. This suggests that the use of retardant did not meaningfully influence the model’s ability to predict whether ROS would be reduced 12 h later, and that environmental and contextual variables played a far more significant role.

The evaluation using the synthetic-only model further reinforces the lack of clear evidence that aerial suppression efforts significantly contributed to reducing ROS. Among the drops where the fire’s ROS actually slowed, the model predicted that 64% would have slowed even in the absence of retardant. This suggests that, in many cases where suppression efforts appeared to be successful, the observed slowing may have occurred regardless of intervention, aligning with conditions the model associated with natural deceleration. Furthermore, if aerial retardant had been a strong driver in reducing fire spread, we would have expected a substantial number of the predicted-to-persist cases to exhibit slowed ROS in reality. However, only about 15% of those drops actually resulted in reduced ROS, while a large majority continued to exhibit persistent spread. This outcome suggests that in most cases, the presence of a retardant drop did not correspond to a meaningful deviation from the fire behavior expected without suppression.

To further evaluate whether the inclusion of real drops influenced model predictions, we applied the full model and the synthetic-only model to the real drops in the testing set and compared their classification outcomes. Using McNemar’s test, a statistical method designed to assess differences between paired categorical outcomes, we found no significant difference between the two models’ predictions (). This result suggests that, despite the full model having access to the real drop indicator variable, its predictions on real drops were statistically indistinguishable from those of the synthetic-only model, further reinforcing the limited predictive value of the real drop flag.

Overall, the findings do not provide strong empirical support for the conclusion that aerial suppression efforts were a consistent or substantial factor in reducing rate of spread over the 12-h periods between observed perimeters in the fires analyzed. While this does not preclude the possibility that suppression can be effective over shorter timescales or under certain conditions, the results from both the full and synthetic-only models, together with the McNemar’s test indicating no significant difference in predictive outcomes, suggest limited evidence within this dataset and modeling framework that suppression alone reliably alters wildfire behavior on a 12-h timeframe. These results highlight the importance of continued research into the effectiveness of retardant drops, particularly given the considerable costs of these operations and the need for a clearer understanding of their expected outcomes.

4.1. Modeling Limitations

One limitation of our modeling approach is the potential for overfitting, a known tendency of random forest classifiers. This is especially true when working with high-dimensional or imbalanced data. We took steps to reduce this risk by carefully splitting the data for training and testing the model, ensuring that all drops associated with a given fire were kept within a single split, and by focusing on balanced accuracy during evaluation. Additionally, the use of a binary classification framework introduces another source of uncertainty. The decision to classify retardant effects into two categories, along with the specific cutoff used to distinguish between them, is somewhat arbitrary and simplifies what is inherently a continuous and context-dependent process.

Another limitation of our approach is that the wildfire ROS is only calculated along the mapped fire perimeters, rather than across the entire burn area or throughout the full time between observations. As a result, fire activity occurring between perimeters—such as rapid spread during wind events or slowed progression following suppression efforts—may go undetected. This spatial and temporal discretization means our ROS estimates reflect a simplified view of fire behavior, focused on the leading edge of the fire. While this provides useful insights into perimeter-scale dynamics, it does introduce some uncertainty in interpreting ROS as a fully comprehensive measure of fire spread.

The set of available predictive features presents its own limitation. Some key drivers of fire behavior, most notably wind, were not included in our dataset due to the lack of reliable, high-resolution wind data at the spatial and temporal scales required for analysis. Wind plays a critical role in shaping fire direction, intensity, and rate of spread, and its absence likely reduced the model’s ability to account for key mechanisms underlying fire growth and suppression effectiveness. Also, the environmental data incorporated into our analysis varied in spatial resolution, ranging from fine-scale (30 m) to coarse-scale (4 km). This inconsistency may have introduced noise or bias in the feature values associated with each drop, particularly in areas with heterogeneous terrain or vegetation. As a result, some modeled relationships may reflect mismatches in data granularity rather than true ecological or suppression effects.

Some of these limitations stem from challenges inherent in quantifying fire behavior and suppression effectiveness at scale. Before settling on our final modeling framework, we explored several alternative strategies that ultimately proved unfeasible. One such approach involved predicting ROS across all points along the fire perimeters. Our goal was to build an accurate model of fire spread, which could then be used to assess the influence of retardant drops relative to to expected spread patterns. However, accurately modeling ROS everywhere proved difficult, with predictions lacking sufficient accuracy. As a result, we shifted toward the counterfactual framework using synthetic drops for comparison.

We also considered a matched comparison strategy by examining areas adjacent to actual retardant drops, aiming to compare treated and untreated regions under similar conditions. While this approach offered an intuitive path to isolating suppression effects, we found it difficult to automate at scale. In many cases, multiple drops were clustered in the same area, making it difficult to find adjacent zones that were truly free of suppression. Furthermore, to ensure valid comparisons, the adjacent areas would need to be aligned with the fire front—a condition not often met given how drops are deployed in practice. These spatial and geometric complexities made it impractical to implement a systematic matching approach across the full dataset. An illustration of these challenges is shown in

Figure 8.

4.2. Limitations of Interpretations

While our results suggest a lack of strong empirical support for the consistent effectiveness of aerial suppression in reducing wildfire ROS, it is important to clarify that this does not constitute evidence against its potential utility. Rather, our findings indicate that, within the scope of our dataset and modeling framework, we were unable to isolate a clear and systematic effect of aerial retardant drops on slowing fire spread. This distinction is critical: the absence of detected impact should not be equated with proof of ineffectiveness. There are numerous potential reasons why suppression effects may not have emerged clearly in our analysis, including limitations in our ability to measure relevant fire dynamics, the granularity of available data, and the complex, context-specific goals of suppression operations.

A key consideration in interpreting suppression effectiveness is the motivation behind each flight. Aerial firefighting missions are not always intended to slow the forward spread of a fire. According to the Aerial Firefighting Use and Effectiveness (AFUE) study, suppression aircraft may be deployed to achieve a range of objectives, including reducing flame length and intensity, preventing spotting, protecting specific values at risk, or supporting ground operations [

7,

9]. Our dataset does not include detailed records of the operational intent behind each retardant drop, making it difficult to evaluate whether our ROS-based metric aligns with the intended outcome. Despite this limitation, approximately 60% of the drops in our dataset were carried out by large airtankers—aircraft that, according to AFUE reports, are most commonly tasked with delaying or halting the spread of the main fire front. Therefore, assessing changes in ROS remains a relevant, if imperfect, lens through which to evaluate their effectiveness.

4.3. Comparison to Existing Literature

Previous studies have provided insights into the conditions under which aerial suppression may be most effective, offering guidance on when and where these resources could be optimally deployed. For example, Wheatley et al. [

11] identified environmental and operational factors that predicted initial attack success, suggesting that air resources could be more strategically allocated to fires with a higher probability of containment. Similarly, Bryan [

13] found that large airtankers were particularly effective in reducing flame intensity and slowing fire growth when used in grass and shrub fuel types and in conjunction with ground efforts. These findings point to context-specific conditions that may influence suppression outcomes. In contrast, our analysis did not reveal consistent patterns linking retardant drops to reductions in fire spread. Our results do not contradict these earlier findings but rather reflect the difficulty of detecting generalized suppression effects in large, heterogeneous datasets.

Our results align more closely with those reported by Katuwal et al. [

10], who found that aerial resources, specifically helicopters and air tankers, did not significantly contribute to controlled fireline length across a large sample of wildfires. While our analysis focused on ROS rather than fireline control, both suggest limited large-scale measurable impacts from aerial suppression efforts. Like Katuwal et al. [

10], we also encountered the challenge of interpreting suppression effectiveness without access to detailed operational objectives. In both cases, the lack of mission-specific context limits the ability to fully assess whether the observed outcomes reflect a failure of effectiveness or a mismatch between metric and intent. The alignment between our results and those of prior studies reinforces the need for clearer operational metadata and more targeted metrics when evaluating the effectiveness of aerial suppression strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness of aerial retardant drops in slowing wildfire ROS using a modeling framework that incorporated both real and synthetic drop data. Despite strong model performance in predicting ROS outcomes, the results did not provide compelling evidence that aerial suppression efforts were a primary driver of reduced fire spread rates over the 12-h periods between mapped perimeters used in this analysis. While aerial suppression may be critical, the predictive signal of whether a drop actually occurred was dominated by environmental and topographic factors in the 62 observed Oregon fires. The low importance of the real-versus-synthetic drop indicator in our full model, along with counterfactual results from the synthetic-only model, suggests that many instances of reduced ROS may have occurred independent of suppression. These findings underscore the complexity of evaluating suppression effectiveness and the limitations of using generalized metrics across large and heterogeneous datasets. Importantly, this does not imply that aerial suppression is ineffective, but rather that its measurable influence may occur over shorter timescales or in specific operational contexts that are not captured at the 12-h resolution of the available data. This highlights the need for more targeted data collection, particularly regarding operational intent, timing, and localized environmental conditions, to improve future assessments.

Building on the findings of this study, future research could benefit from key improvements in both data collection and modeling. A major need is for more detailed drop-level data, particularly information on the intended purpose of each aerial retardant drop. Understanding whether a drop was deployed to reduce fire intensity, protect assets, or slow fire spread would enable a more nuanced assessment of aerial suppression effectiveness. In addition, incorporating wind speed and direction—key drivers of fire behavior that were not available in this study—along with fire intensity data and higher-resolution versions of the existing climate datasets would enhance the model’s ability to capture dynamic fire-environment interactions. A tool such as WindNinja, which generates wind fields using terrain and meteorological inputs, could be explored as a source of localized wind data for future modeling efforts. Finally, access to more frequent and accurate fire perimeter updates would allow for more precise tracking of fire spread, improving the accuracy of ROS calculations and enabling evaluation of suppression impacts at shorter temporal intervals where effects may be more evident.

Recent advances in machine learning have produced foundational models, which are systems with millions of parameters trained on terabytes of data. Presently, a set of such models has been trained using massive sets of geospatial and satellite data to classify features on the Earth’s surface [

23]. These models offer promising opportunities to improve future assessments of wildfire suppression effectiveness. By capturing complex spatial and temporal patterns that traditional approaches may overlook, they can support more accurate predictions of fire behavior and suppression outcomes. Leveraging transfer learning, these models can be fine-tuned for fire-specific tasks even with limited labeled data. In particular, their ability to integrate multimodal inputs—such as optical imagery, topography, and climate variables—could enhance sensitivity to localized environmental conditions, especially when high-resolution and high-frequency datasets are available. Incorporating such models into future work could provide a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between environmental factors and suppression actions across diverse fire contexts.

As wildfire activity intensifies and finite suppression resources are spread thinly over a growing fire landscape, continued efforts to improve both the quality of operational data and the sophistication of analytical tools will be essential for making informed, effective fire management decisions. This study underscores the promise of large-scale, data-driven analysis in evaluating aerial wildfire suppression tactics, while also highlighting the key challenges that must be addressed to fully harness its potential in shaping future fire management strategies.