Association Between Call Volume and Perceptions of Stress and Recovery in Active-Duty Firefighters

Abstract

1. Introduction

Study Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

Perceived Stress and Recovery

2.4. Statistical Analysis

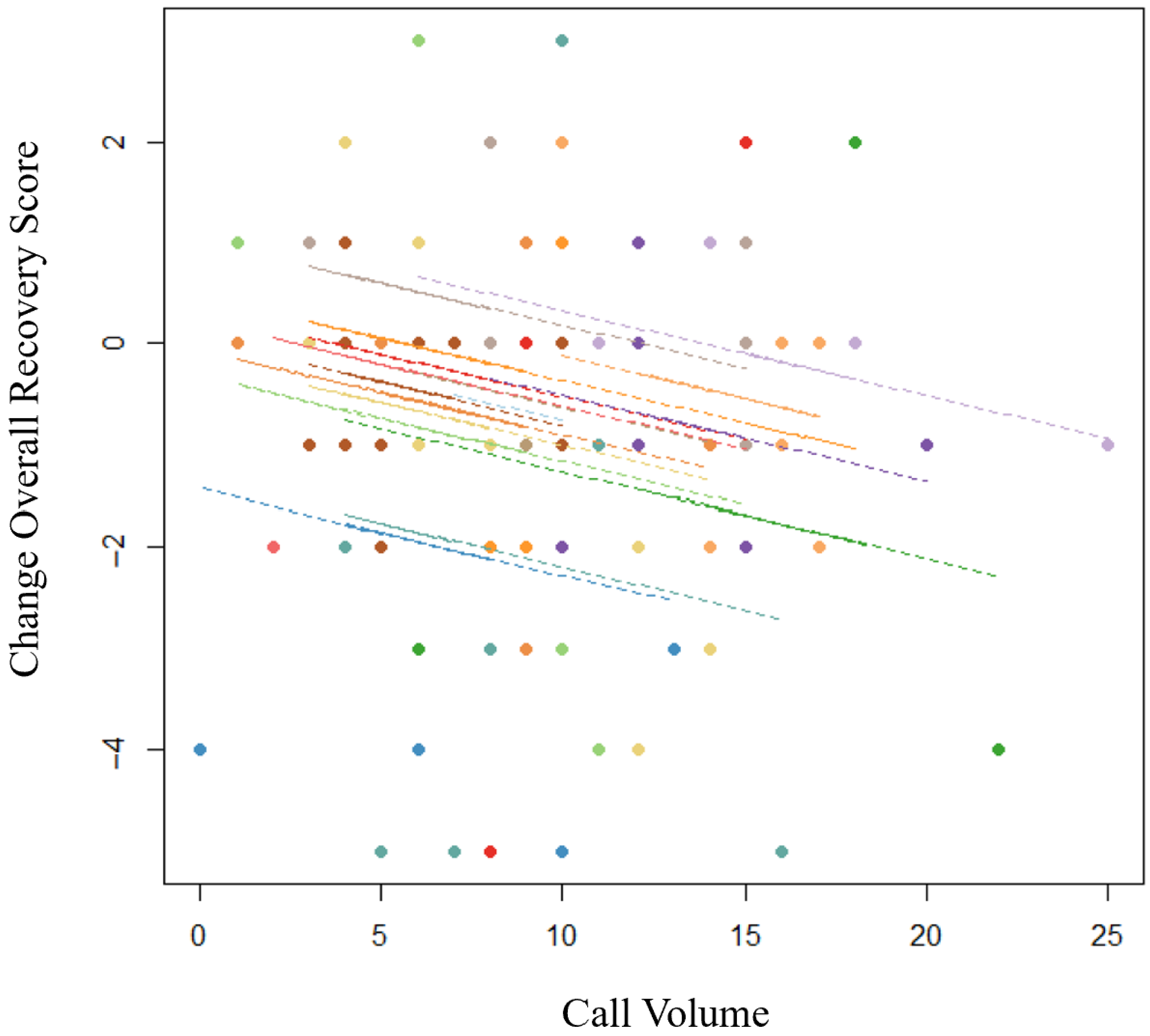

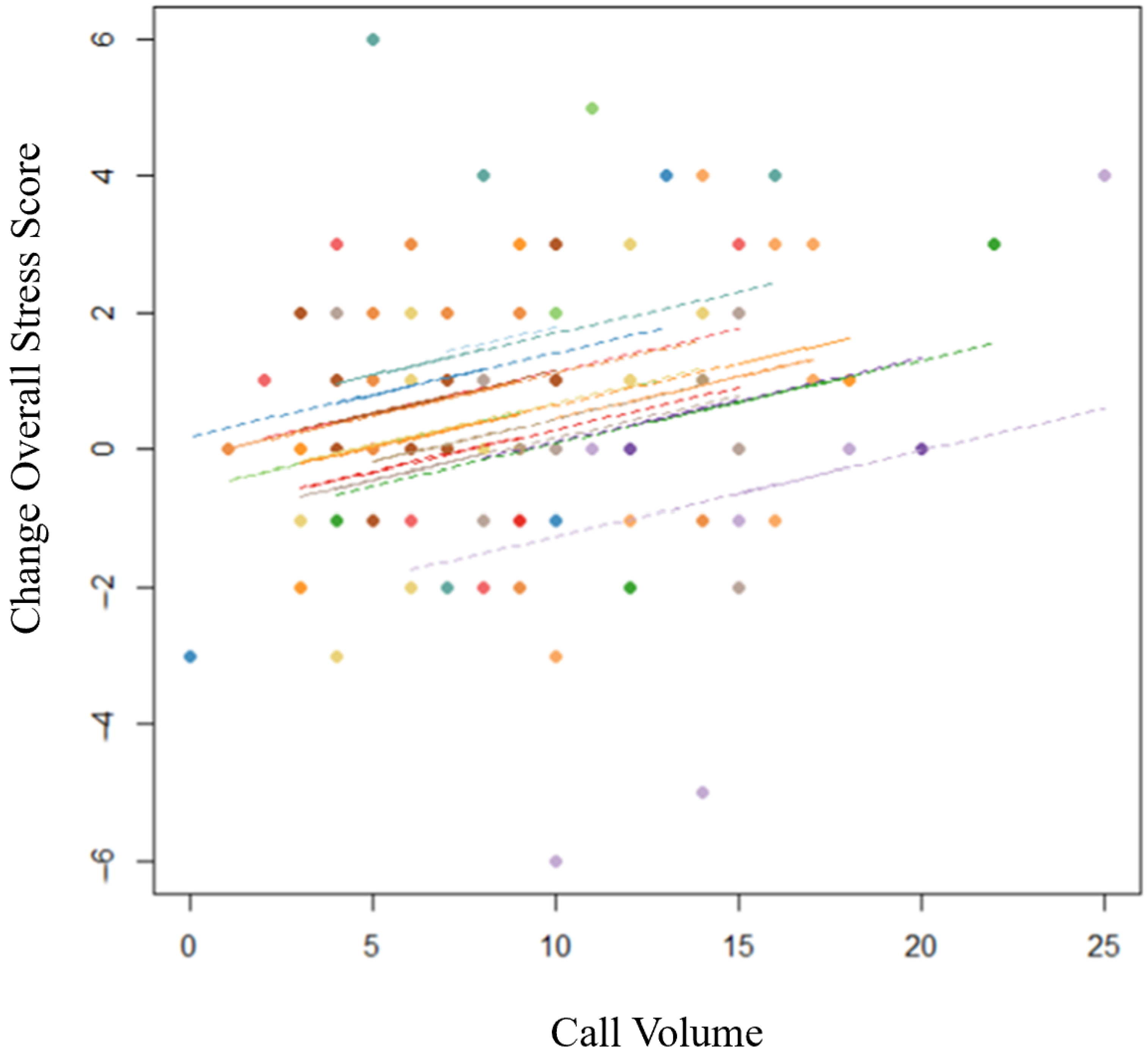

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campbell, R. Firefighter injuries on the fireground. NFPA J. 2024. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/research/nfpa-research/fire-statistical-reports/patterns-of-firefighter-fireground-injuries (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Fahy, R.F.; Evarts, B.; Stein, G.P. U.S. Fire Department Profile 2020. NFPA J. 2022. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/research/nfpa-research/fire-statistical-reports/us-fire-department-profile (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Isaac, G.M.; Buchanan, M.J. Extinguishing stigma among firefighters: An examination of stress, social support, and help-seeking attitudes. Psychology 2021, 12, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.C.; Vega, L.; Kohalmi, A.L.; Roth, J.C.; Howell, B.R.; Van Hasselt, V.B. Enhancing mental health treatment for the firefighter population: Understanding fire culture, treatment barriers, practice implications, and research directions. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2020, 51, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrel, N.A.; Steffen, L.E.; Meyer, E.C.; Kruse, M.I.; Knight, J.A.; Zimering, R.T.; Gulliver, S.B. A revised measure of occupational stress for firefighters: Psychometric properties and relationship to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance abuse. Psychol. Serv. 2011, 8, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological aspects of workload. In New Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology; Drenth, P.J.D., Thierry, H., de Wolff, C.J., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kaikkonen, P.; Lindholm, H.; Lusa, S. Physiological load and psychological stress during a 24-hour work shift among Finnish firefighters. J. Occup. Env. Med. 2007, 59, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.D.; DeJoy, D.M.; Dyal, M.-A.; Huang, G. Impact of work pressure, work stress and work-family conflict on firefighter burnout. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2018, 74, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; Cardinale, M.; Murray, A.; Gastin, P.; Kellmann, M.; Varley, M.C.; Gabbett, T.J.; Coutts, A.J.; Burgess, D.J.; Gregson, W.; et al. Monitoring athlete training loads: Consensus statement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Marcora, S.M.; Coutts, A.J. Internal and external training load: 15 years on. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, R.A.; Cornell, D.J.; Meyer, B.B.; Azen, R.; Laiosa, M.D.; Ebersole, K.T. Workloads of emergency call types in active-duty firefighters. Merits 2024, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igboanugo, S.; Bigelow, P.L.; Mielke, J.G. Health outcomes of psychosocial stress within firefighters: A systematic review of the research landscape. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Mullins-Jaime, C.; Dayl, M.A.; DeJoy, D.M. Stress, burnout and diminished safety behaviors: An argument for Total Worker Health® approaches in the fire service. J. Saf. Res. 2010, 75, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellmann, M.; Kölling, S. Recovery and Stress in Sport: A Manual for Testing and Assessment; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, S.M.; Drew-Nord, D.C.; Neitzel, R.L.; Wallhagen, M.I.; Bates, M.N.; Hong, O.S. Characteristics and predictors of occupational injury among career firefighters. Work. Health Saf. 2018, 66, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluntke, U.; Gerke, S.; Sridhar, A.; Weiss, J. Evaluation and classification of physical and psychological stress in firefighters using heart rate variability. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney, G.; Jennings, K.S.; Britt, T.S.; Sliter, M.T. Occupational stress and mental health symptoms: Examining the moderating effect of work recovery strategies in firefighters. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastug, G.; Ergul-Topcu, A.; Ozel-Kizil, E.T.; Ergun, O.F. Secondary traumatization and related psychological outcomes in firefighters. J. Loss Trauma 2019, 24, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, S.A.; Poston, W.S.C.; Haddock, C.K.; Murphy, B. Firefighting and mental health: Experiences of repeated exposure to trauma. Work 2016, 53, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, N.; Kinman, G. Job demands, resources, and work-related well-being in UK firefighters. Occup. Med. 2020, 69, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenttä, G.; Hassmén, P. Overtraining and recovery. A conceptual model. Sports Med. 1998, 26, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijman, T.F. Over Fatigue; Psychological Studies on the Perception of Workload Effects. Doctoral Dissertation, Groningen University, Groningen, The Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra, F.R.H.; Cropley, M.; Rydstedt, L. From recovery to regulation: An attempt to reconceptualize ‘recovery from work’. Stress Health 2014, 30, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, K.C.; Vaughn Becker, D.; Adams, G. Hot cognition: Exploring the relationship between excessive call volume and cognitive fatigue. Fire. Health. Saf. 2011, 7, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, S.L.; Shannon, M.A.; Hurtado, D.A.; Shea, S.A.; Bowles, N.P. Interactions between home, work, and sleep among firefighters. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands–Resources model of burnout. J. App. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job demands-resources theory: Ten years later. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölling, S.; Schaffran, P.; Bibbey, A.; Drew, M.; Raysmith, B.; Nässi, A.; Kellmann, M. Validation of the Acute Recovery and Stress Scale (ARSS) and the Short Recovery and Stress Scale (SRSS) in three English-speaking regions. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramel, W.; Schram, B.; Canetti, E.; Orr, R. An examination of subjective and objective measures of stress in tactical populations: A scoping review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakdash, J.Z.; Marusich, L.R. Repeated measures correlation. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, T. Correlation coefficients for a study with repeated measures. Comp. Math. Meth. Med. 2020, 1, 7398324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelmini, J.D.; Gribble, P.A.; Abel, M.G.; Whitehurst, L.N.; Heebner, N.R. The influence of emergency call volume on occupational workload and sleep quality in urban firefighters. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 66, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidor, M.; Weller, A.; Babkoff, H. How sleep is related to fatigue. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2023, 8, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, J.J.; Ginter, D.R.; Sadowsky, B. Sleep quality versus sleep quantity: Relationships between sleep and measures of health, well-being and sleepiness in college students. J. Psychosom. Res. 1997, 42, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubbs, A.S.; Dollish, H.K.; Fernandez, F.; Grandner, M.A. The basics of sleep physiology and behavior. In Sleep and Health; Grandner, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S.; Binnewies, C.; Mojza, E.J. “Did you have a nice evening?” A day-level study on recovery experiences, sleep, and affect. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S.J.; Aisbett, B.; Tait, J.L.; Turner, A.I.; Ferguson, S.A.; Main, L.C. The acute physiological stress response to an emergency alarm and mobilization during the day and at night. Noise Health 2016, 18, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciniak, R.A.; Tesch, C.J.; Ebersole, K.T. Heart rate response to alarm tones in firefighters. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 94, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Dyal, M.-A.; Dejoy, D.M. Firefighter stress, anxiety, and diminished compliance-oriented safety behaviors: Consequences of passive safety leadership in the fire service? Fire 2023, 6, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1987, 57, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland-Winkler, A.M.; Hamil, B.K.; Greene, D.R.; Kohler, A.A. Strategies to improve physiological and psychological components of resiliency in firefighters. Physiologia 2023, 3, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, P.A.; Krueger, G.A. Hours of Boredom, Moments of Terror: Temporal Desynchrony in Military and Security Force Operations. Defense & Technology, National Defense University Center for Technology and National Security Policy. 2010. Available online: https://digitalcommons.ndu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=defense-tech-papers (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- National Fire Protection Association. Fire Department Calls. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/research/nfpa-research/fire-statistical-reports/fire-department-calls (accessed on 1 June 2024).

| Characteristic | N | Percent by Category (N = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 14 | 87.5% |

| Female | 2 | 12.5% |

| Rank | ||

| Firefighter | 10 | 62.5% |

| Heavy Equipment Operator | 2 | 12.5% |

| Lieutenant | 4 | 25% |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 years | 3 | 18.8% |

| 25–34 years | 3 | 18.8% |

| 35–44 years | 9 | 56.2% |

| 45–54 years | 1 | 6.2% |

| SRSS Item | Pre-Shift | Post-Shift | Pre- to Post- Shift Change Score Δ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical Performance Capability | 4.70 (0.96) | 3.88 (1.34) | −0.81 (1.29) * |

| 2. Mental Performance Capability | 4.64 (0.99) | 3.80 (1.50) | −0.84 (1.47) * |

| 3. Emotional Balance | 4.74 (1.15) | 4.00 (1.52) | −0.74 (1.51) * |

| 4. Overall Recovery | 4.54 (1.09) | 3.78 (1.53) | −0.76 (1.56) * |

| 5. Muscular Stress | 2.54 (1.59) | 2.76 (1.46) | 0.22 (1.66) |

| 6. Lack of Activation | 2.26 (1.57) | 2.63 (1.58) | 0.37 (1.61) * |

| 7. Negative Emotional State | 1.87 (1.63) | 2.21 (1.70) | 0.34 (1.59) * |

| 8. Overall Stress | 2.17 (1.55) | 2.67 (1.72) | 0.51 (1.73) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wahl, C.A.; Marciniak, R.A.; Meyer, B.B.; Ebersole, K.T. Association Between Call Volume and Perceptions of Stress and Recovery in Active-Duty Firefighters. Fire 2025, 8, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070268

Wahl CA, Marciniak RA, Meyer BB, Ebersole KT. Association Between Call Volume and Perceptions of Stress and Recovery in Active-Duty Firefighters. Fire. 2025; 8(7):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070268

Chicago/Turabian StyleWahl, Carly A., Rudi A. Marciniak, Barbara B. Meyer, and Kyle T. Ebersole. 2025. "Association Between Call Volume and Perceptions of Stress and Recovery in Active-Duty Firefighters" Fire 8, no. 7: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070268

APA StyleWahl, C. A., Marciniak, R. A., Meyer, B. B., & Ebersole, K. T. (2025). Association Between Call Volume and Perceptions of Stress and Recovery in Active-Duty Firefighters. Fire, 8(7), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070268