Towards Integrated Fire Management: Strengthening Forest Fire Legislation and Policies in the Andean Community of Nations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Legal Context Assessment of Forest Fires in the Region

- SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were used to identify previous studies and comparative analyses in all countries.

- For Colombia, the FAOLEX Database [62] was consulted, providing access to environmental and natural resource regulations. In addition, information was taken from the Official Gazette, which is the means of publishing laws for the knowledge of the state.

2.3. Analysis of Public Policies for Forest Fire Management in the Region

2.4. Collection of Primary Information on Laws and Public Policies in the Andean Community of Nations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. A Comparative Analysis of Forest Fire Laws in the Andean Region

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Public Policies as Precedents for Fire Management in the Andean Region

3.3. Comparative Evaluation of Legal Frameworks and Public Policies on Forest Fires in the Andean Community

3.4. Perceptions of Key Stakeholders Regarding Legislation and Public Policies Related to Forest Fires in the Andean Community

3.5. The Benefits and Potential Risks of Prevention-Focused Forest Fire Laws and Public Policies in the Andean Region

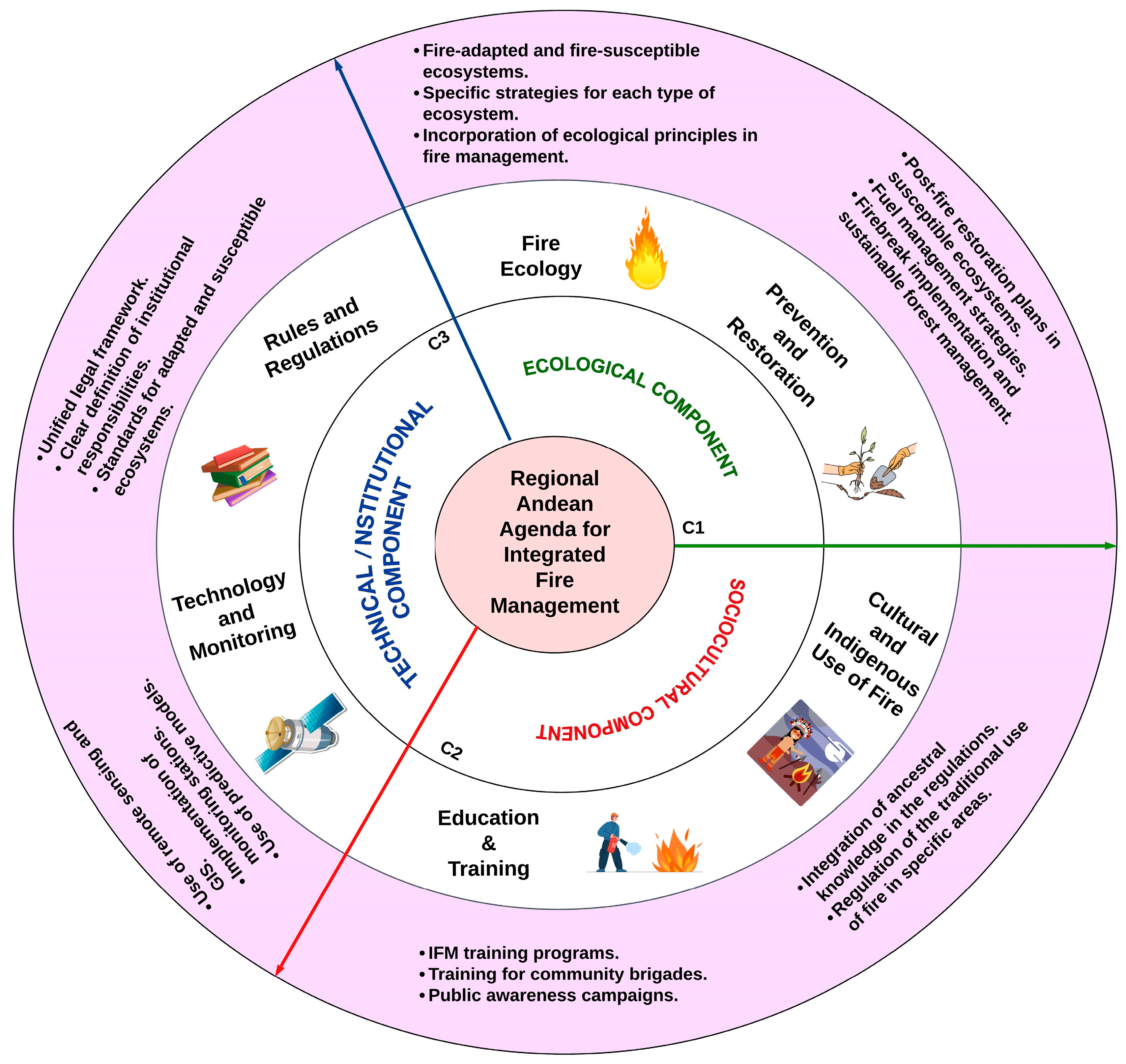

3.6. Proposal for the Creation of a Regional Andean Agenda for Integrated Fire Management (RAAIFM)

3.6.1. Ecological Component

3.6.2. Sociocultural Component

3.6.3. Technological–Institutional Component

4. Conclusions

- Ecological: This includes the recognition of fire-adapted and fire-sensitive ecosystems, post-fire restoration, and ecological zoning.

- Sociocultural: This emphasizes the integration of ancestral knowledge about fire, community education, and intercultural dialogue.

- Technical–institutional: This focuses on intersectoral coordination, technological tools for monitoring, multisectoral financing, and legal harmonization, including urban and peri-urban fire legislation.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Odello, M.; Seatzu, F. Latin American and Caribbean International Institutional Law; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tarver, H.M. The History of Venezuela; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Contipelli, E. La Comunidad Andina de Naciones y la evolución del proceso de integración socioeconómico en Latinoamérica. Rev. De Derecho Público 2016, 64, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A.; Correa, M. ¿Qué pasa con la Comunidad Andina de Naciones-CAN? Pap. Político 2007, 12, 591–632. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ochoa, J.; Peña, M.; Duarte, S. La Comunidad Andina: Un paradigma de Integración Económica en Latinoamérica. REICE Rev. Electrónica De Investig. En Cienc. Económicas 2014, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Do institutions matter for regional development? Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1034–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao, B.; Mistry, J.; Millán, A.; Berardi, A. Sharing multiple perspectives on burning: Towards a participatory and intercultural fire management policy in Venezuela, Brazil, and Guyana. Fire 2019, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAFOR. Programa de Manejo del Fuego 2020–2024; Gobierno de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Canton, H. Andean Community of Nations: (Comunidad Andina de Naciones-CAN). In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- Stang, M.F. El dispositivo jurídico migratorio en la Comunidad Andina de Naciones. Migr. Y Política El Estado Interrogado 2009, 301, 301–353. [Google Scholar]

- Stovel, E.M. Concepts of ethnicity and culture in Andean archaeology. Lat. Am. Antiq. 2013, 24, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, F.; Ramírez, P.; Iñiguez, C.; Günter, S.; Maraun, M.; Scheu, S. Conversion of Andean montane forests into plantations: Effects on soil characteristics, microorganisms, and microarthropods. Biotropica 2020, 52, 1142–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Sánchez-Cordero, V.; Londoño, M.C.; Fuller, T. Systematic conservation assessment for the Mesoamerica, Chocó, and Tropical Andes biodiversity hotspots: A preliminary analysis. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 1793–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, J.; Youg, B.E.; Beck, S.; Comer, P.; Córdova, J.H.; Dyson, J.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.M. Plant and animal endemism in the eastern Andean slope: Challenges to conservation. BMC Ecol. 2012, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Rostamy, A.; Najafi, F.; Dey, D.C. Effect of fire severity on physical and biochemical soil properties in Zagros oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) forests in Iran. J. For. Res. 2017, 28, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, Y.; Girardin, C.A.; Goldsmith, G.R.; Doughty, C.E.; Salinas, N.; Metcalfe, D.B.; Silman, M. The variation of productivity and its allocation along a tropical elevation gradient: A whole carbon budget perspective. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruijnzeel, L.A. Hydrological Impacts of Converting Tropical Montane Cloud Forest to Pasture, with Initial Reference to Northern Costa Rica; Final Technical Report DFID-FRP Project No. R7991; Vrije Universiteit: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rovere, A.E. Review of publications regarding restoration in the Andean Patagonian forest region of Argentina New Phytologist. Bosque 2023, 44, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeier-Young, M.C.; Gillett, N.P.; Zwiers, F.W.; Cannon, A.J.; Anslow, F.S. Attribution of the Influence of Human-Induced Climate Change on an Extreme Fire Season. Earth’s Future 2018, 7, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali, A.; Sá, A.C.; Ervilha, A.R.; Trigo, R.M.; Fernandes, P.M.; Pereira, J.M. Fire spread predictions: Sweeping uncertainty under the rug. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 592, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, R.C.; Fusco, E.; Bradley, B.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Balch, J. Human-Related Ignitions Increase the Number of Large Wildfires across U.S. Ecoregions. Fire 2018, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Williams, A.P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11770–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mickley, L.J.; Liu, P.; Kaplan, J.O. Trends and spatial shifts in lightning fires and smoke concentrations in response to 21st century climate over the national forests and parks of the western United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 8827–8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Paladines, V.; Fries, A.; Hinojosa, M.B.; Oña, A.; Álvarez, L.J.; Benítez, Á.; García-Ruiz, R. Effects of low-severity fire on soil physico-chemical properties in an Andean Páramo in Southern Ecuador. Fire 2023, 6, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.C.; Quezada, L.C.; Álvarez, L.J.; Loján-Córdova, J.; Carrión-Paladines, V. Indigenous use of fire in the paramo ecosystem of southern Ecuador: A case study using remote sensing methods and ancestral knowledge of the Kichwa Saraguro people. Fire Ecol. 2023, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenteras, D.; Schneider, L.; Dávalos, L.M. Fires in protected areas reveal unforeseen costs of Colombian peace. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrión-Paladines, V.; Correa-Quezada, L.; Valdiviezo, H.; Zurita, J.; Pereddo, A.; Zambrano, M.; Loján-Córdova, J. Exploring the ethnobiological practices of fire in three natural regions of Ecuador, through the integration of traditional knowledge and scientific approaches. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2024, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Zubieta, R.; Ccanchi, Y.; Martínez, A.; Paucar, Y.; Alvarez, S.; Ayala, F. Seasonal Effects of Wildfires on the Physical and Chemical Properties of Soil in Andean Grassland Ecosystems in Cusco, Peru: Pending Challenges. Fire 2024, 7, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillo, M.; Tonini, M.; Mapelli, A.; Fiorucci, P. Spatial Assessment of Wildfires Susceptibility in Santa Cruz (Bolivia) Using Random Forest. Geosciences 2021, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.P.; Baque, M.J.; Pionce, G.A.; Jimenez, A.; Manrique, T.O. Communication Program on Forest Fire Prevention in the Paján Sector, Manabí, Ecuador. Perspect. Rural. 2018, 31, 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- Estacio, J.; Narváez, N. Incendios forestales en el Distrito Metropolitano de Quito (DMQ): Conocimiento e intervención pública del riesgo. Let. Verdes 2012, 11, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, M.C.; Espelta, J.M.; González, T.M.; Armenteras, D. Fire reduces taxonomic and functional diversity in Neotropical moist seasonally flooded forests. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 21, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Celino, V.; Kainer, K.A. Living with Fire: Agricultural Burning by Quechua Farmers in the Peruvian Andes. Hum. Ecol. 2024, 52, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E. Fire intensity, fire severity and burn severity: A brief review and suggested usage. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C.; Rejmánek, M.; Miller, J.E.; Welch, K.R.; Weeks, J.; Safford, H. The species diversity x fire severity relationship is hump-shaped in semiarid yellow pine and mixed conifer forests. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, D.; González-De Vega, S.; Lozano, E.; García-Orenes, F.; Mataix-Solera, J.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; De Las Heras, J. The burn severity and plant recovery relationship affect the biological and chemical soil properties of Pinus halepensis Mill. stands in the short and mid-terms after wildfire. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 235, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dove, N.C.; Safford, H.D.; Bohlman, G.N.; Estes, B.L.; Hart, S.C. High-severity wildfire leads to multi-decadal impacts on soil biogeochemistry in mixed-conifer forests. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, K.K.; Bhardwaj, A.K. Incidence of Forest Fire in India and Its Effect on Terrestrial Ecosystem Dynamics, Nutrient and Microbial Status of Soil. Int. J. Agric. For. 2015, 5, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sulwiński, M.; Mętrak, M.; Wilk, M.; Suska-Malawska, M. Smouldering fire in a nutrient-limited wetland ecosystem: Long-lasting changes in water and soil chemistry facilitate shrub expansion into a drained burned fen. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.; Ibáñez, T.S.; Santín, C.; Doerr, S.H.; Nilsson, M.C.; Holst, T.; Kljun, N. Boreal Forest soil carbon fluxes one year after a wildfire: Effects of burn severity and management. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4181–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordán, A.; Gordillo-Rivero, Á.J.; García-Moreno, J.; Zavala, L.M.; Granged, A.J.; Gil, J.; Neto-Paixão, H.M. Post-fire evolution of water repellency and aggregate stability in Mediterranean calcareous soils: A 6-year study. Catena 2014, 118, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Francos, M.; Brevik, E.C.; Ubeda, X.; Bogunovic, I. Post-fire soil management. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 5, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twidwell, D.; Bielski, C.H.; Scholtz, R.; Fuhlendorf, S.D. Advancing Fire Ecology in 21st Century Rangelands. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 78, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLauchlan, K.K.; Higuera, P.E.; Miesel, J.; Rogers, B.M.; Schweitzer, J.; Shuman, J.K.; Watts, A.C. Fire as a fundamental ecological process: Research advances and frontiers. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 2047–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, C.I.; Swetnam, T.W.; Ferguson, T.J.; Liebmann, M.J.; Loehman, R.A.; Welch, J.R.; Kiahtipes, C.A. Native American fire management at an ancient wildland–urban interface in the Southwest United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2018733118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Calderón, L.P.; Rodríguez-Trejo, D.A.; Villanueva-Díaz, J.; Bilbao, B.A.; Alvarez-Gordillo, G.D.C.; Vera-Cortés, G. Historical fire ecology and its effect on vegetation dynamics of the Lagunas de Montebello National Park, Chiapas, México. iForest-Biogeosciences For. 2021, 14, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgis, M.A.; Zeballos, S.R.; Carbone, L.; Zimmermann, H.; von Wehrden, H.; Aguilar, R.; Jaureguiberry, P. A review of fire effects across South American ecosystems: The role of climate and time since fire. Fire Ecol. 2021, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, C.; Knox, M.A. Prehistoric burning in the Pacific Northwest: Human versus climatic influences. In Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 195–231. [Google Scholar]

- Tubbesing, C.L.; York, R.A.; Stephens, S.L.; Battles, J.J. Rethinking fire-adapted species in an altered fire regime. Ecosphere 2020, 11, e03091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Edgeley, C.M. Fire adapted community. In Encyclopedia of Wildfires and Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) Fires; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 320–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dharap, A.V.; Shigwan, B.K.; Datar, M.N. Dicliptera polymorpha (Acanthaceae): A new pyrophytic species from northern Western Ghats, India. Kew Bull. 2024, 79, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao, B.A.; Leal, A.V.; Méndez, C.L. Indigenous Use of Fire and Forest Loss in Canaima National Park, Venezuela. Assessment of and Tools for Alternative Strategies of Fire Management in Pemón Indigenous Lands. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, S.J. Fire: Nature and Culture; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yangua-Solano, E.; Carrión-Paladines, V.; Benítez, Á. Effects of Fire on Pyrodiversity of Terricolous Non-Tracheophytes Photoautotrophs in a Páramo of Southern Ecuador. Diversity 2023, 15, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulé, P.Z.; Ramos-Gómez, M.; Cortés-Montaño, C.; Miller, A.M. Fire regime in a Mexican forest under indigenous resource management. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuvieco, E.; Martínez, S.; Román, M.V.; Hantson, S.; Pettinari, M.L. Integration of ecological and socio-economic factors to assess global vulnerability to wildfire. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2014, 23, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardel-Peláez, E.J.; Pérez-Salicrup, D.; Alvarado, E.; Morfín-Ríos, J.E. Principios y Criterios para el Manejo del Fuego en Ecosistemas Forestales: Guía de Campo; Comisión Nacional Forestal: Zapopan, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, J.; Schmidt, I.B.; Eloy, L.; Bilbao, B. New perspectives in fire management in South American savannas: The importance of intercultural governance. Ambio 2019, 48, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlamento Andino. Resolución No. 22 Sobre Incendios Forestales en los Países Miembros del Parlamento Andino. 2024. Available online: https://www.parlamentoandino.org/index.php/actualidad/noticias/1505-resolucion-n-22-sobre-los-incendios-forestales-en-los-paises-miembros-del-parlamento-andino (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Secretaría General de la Comunidad Andina, Estrategia Regional de Biodiversidad para los Países del Trópico Andino. 2005. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/nbsap/rbsap/comunidad-andina-rbsap.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Chen, J.; Di, X.Y. Forest fire prevention management legal regime between China and the United States. J. For. Res. 2015, 26, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Base de datos FAOLEX. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/es/ (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- vLex Global. 2025. Available online: https://app.vlex.com/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Órgano de la República del Ecuador. Registro Oficial. 2025. Available online: https://www.registroficial.gob.ec/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Montiel-Molina, C. Comparative assessment of wildland fire legislation and policies in the European Union: Towards a Fire Framework. Dir. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario Oficial del Bicentenario El Peruano. 2025. Available online: https://diariooficial.elperuano.pe/BoletinOficial (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Organization of American States. 2025. Available online: https://www.oas.org/en/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Órgano Judicial de Bolivia, Tribunal Agroambiental. 2025. Available online: https://www.tribunalagroambiental.bo/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. 2025. Available online: http://www.gacetaoficialdebolivia.gob.bo/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Durigan, G.; Ratter, J.A. The need for a consistent fire policy for Cerrado conservation. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.P.; Quintanilla, A. Evaluación legislativa: Un análisis comparado entre Guatemala y Costa Rica. Rev. Análisis De La Real. Nac. Año 6 2017, 120, 84–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. Using Radar Chart to Evaluate Laws’ Influence on Brownfield Aesthetics for Suggestions of Future Lawmaking in US and China. Master’s Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shutaleva, A. Ecological culture and critical thinking: Building of a sustainable future. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, R.; Kalinichenko, P. On Similarities and Differences of the European Union and Eurasian Economic Union Legal Orders: Is There the ‘Eurasian Economic Union Acquis’? Leg. Issues Econ. Integr. 2016, 43, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargarella, R. Latin American Constitutionalism, 1810–2010: The Engine Room of the Constitution; OUP: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Souther, S.; Colombo, S.; Lyndon, N.N. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge into US public land management: Knowledge gaps and research priorities. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 988126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanteler, D.; Bakouros, I. A collaborative framework for cross-border disaster management in the Balkans. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diario Oficial No. 44097 del 24/07/2000, Ley 599 de 2000, Código Penal Colombia. 2000. Available online: https://www.oas.org/dil/esp/codigo_penal_colombia.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Registro Oficial Suplemento 180 de 10 de Febrero de 2014, Last Modification 17 de Febrero de 2021, Código Orgánico Integral Penal. 2021. Available online: https://app.vlex.com/vid/435777665 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Diario Oficial El Peruano, Decreto Legislativo N° 635, Código Penal de Perú. 2018. Available online: https://diariooficial.elperuano.pe/Normas/obtenerDocumento?idNorma=2 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. Ley Nº 1768 de 10 de Marzo de 1997, Updated in 2003, Código Penal Bolivia. 2003. Available online: https://www.oas.org/juridico/spanish/gapeca_sp_docs_bol1.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Uribe-Uran, V.M. The Birth of a Public Sphere in Latin America during the Age of Revolution. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 2000, 42, 425–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Schulte, E.; Schmuck, G.; Camia, A. The European Forest Fire Information System in the context of environmental policies of the European Union. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 29, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce Calderon, L.; Limón-Aguirre, F.; Rodríguez, I.; Rodriguez-Trejo, D.; Bilbao, B.; Alvarez-Gorrillo, G.; Villanueva-Díaz, J. Fire management in pyrobiocultural landscapes, Chiapas, Mexico. Trop. For. Issues 2022, 61, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registro Oficial Suplemento 418 de 10 de Septiembre de 2004, Ley Forestal y de Conservación de Áreas Naturales y Vida Silvestre. 2004. Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2015/06/Ley-Forestal-y-de-Conservacion-de-Areas-Naturales-y-Vida-Silvestre.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Ministerio del Ambiente, Ley N° 29763, Ley Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre. 2011. Available online: https://www.minam.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Ley-N%C2%B0-29763.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego, Plan Nacional de Investigación Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre 2020–2030. 2020. Available online: https://sinia.minam.gob.pe/sites/default/files/sinia/archivos/public/docs/pniffs_2020_-_2030.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Diario Oficial No. 38.761 del 3 de Abril de 1989, Ley 2111 de 2021, Por Medio del Cual se Sustituye el Título XI De los Delitos Contra los Recursos Naturales y el Medio Ambiente de la Ley 599 de 2000, se Modifica la Ley 906 de 2004 y se Dictan Otras Disposiciones. 2021. Available online: https://www.minambiente.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ley-2111-2021.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Diario Oficial No. 48.411 de 24 de Abril de 2012, Ley 37 de 1989, Por la Cual se dan las Bases para Estructurar el Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Forestal y se Crea el Servicio Forestal. 1989. Available online: https://corponor.gov.co/images/corponor/normatividad/LEYES/Ley%2037%20de%201989.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. Ley N° 1525, Ley de 9 de Noviembre de 2023, Ley Forestal. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/es/c/LEX-FAOC222821/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. Ley N° 1700 de 12 de Julio de 1996, Ley Forestal. 1996. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/bol6960.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. Ley Nro. 1171, Ley del 2 de Mayo de 2019, Ley de Uso y Manejo Racional de Quemas. 2019. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/es/c/LEX-FAOC189056/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Rodriguez, I.; Inturias, M.; Masay, E.; Peña, A. Decolonizing wildfire risk management: Indigenous responses to fire criminalization policies and increasingly flammable forest landscapes in Lomerío, Bolivia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 147, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, M.G. The harmonization, codification and integration of environmental law: A search for definitions. Eur. Energy Environ. Law Rev. 2000, 9, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Sletto, B.; Leal, A.; Bilbao, B.; Sánchez-Rose, I. Apropósito del fuego: Diálogo de saberes y justicia cognitiva en territorios indígenas culturalmente frágiles. Trilogía Cienc. Tecnol. Soc. 2016, 8, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Inturias, M.L. Conflict transformation in indigenous peoples’ territories: Doing environmental justice with a ‘decolonial turn’. Dev. Stud. Res. 2018, 5, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registro Oficial Suplemento 194 de 30 de Abril del 2020, Código Orgánico del Ambiente. 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.ec/regulaciones/codigo-organico-ambiente (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Registro Oficial Edición Especial 114 de 02 de Abril de 2009, Reglamento de Prevención, Mitigación y Protección Contra Incendios. 2009. Available online: https://www.gob.ec/regulaciones/reglamento-prevencion-mitigatorio-proteccion-contra-incendios (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Diario El Peruano, Decreto Supremo Nº 020-2015-MINAGRI, Reglamento para la Gestión de las Plantaciones Forestales y los Sistemas Agroforestales. 2015. Available online: https://sinia.minam.gob.pe/sites/default/files/sinia/archivos/public/docs/ds_020-2015-minagri.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Decreto Supremo Nº 021-2015-MINAGRI, Reglamento para la Gestión Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre en Comunidades Nativas y Comunidades Campesinas. 2015. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/es/c/LEX-FAOC149280/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Abdullah, A. A Review and Analysis of Legal and Regulatory Aspects of Forest Fires in South East Asia; Project FireFight South East Asia PO; International Union for Conservation of Nature [IUCN]: Gland, Switzerland, 2002; p. 6596. [Google Scholar]

- Corona, P.; Ascoli, D.; Barbati, A.; Bovio, G.; Colangelo, G.; Elia, M.; Chianucci, F. Integrated Forest management to prevent wildfires under Mediterranean environments. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2015, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, S.L.; Collins, B.M.; Biber, E.; Fulé, P.Z. US federal fire and forest policy: Emphasizing resilience in dry forests. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.J.; Butler, S.M.; Caputo, J.; Dias, J.; Robillard, A.; Sass, E.M. Family Forest Ownerships of the United States, 2018: Results from the USDA Forest Service, National Woodland Owner Survey; General Technical Report. NRS-199; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Madison, WI, USA, 2021; p. 199.

- Galeano, M.F. Implicaciones de un Modelo para la Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres: Caso Comunidad Andina. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, D.S.; Insuasti, A.B.; Graziani, P.; Carvajal, J.C.; Guayasamín, A.O. “Amazonía sin Fuego” una estrategia para la reducción de incendios forestales y promoción de alternativas al uso del fuego en el Ecuador. Biodiversidade Bras. 2019, 9, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Comunidad Andina, Carta Ambiental Andina. 2020. Available online: https://www.comunidadandina.org/notas-de-prensa/carta-ambiental-andina/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Bosques Andinos, Manejo Sostenible de Paisajes de Montañas. 2015. Available online: https://www.bosquesandinos.org/pba/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Lovreglio, R.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Chas-Amil, M.L.; Ganteaume, A.; Boris Pezzatti, G. Forest fire causes and motivations in the southern and South-Eastern Europe through experts’ perception and applications to current policies. Forests 2022, 13, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.; Rigolot, E.; Fernandes, P.; Montiel, C.; Silva, J.S. Towards Integrated Fire Management; EFI Policy Brief; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2010; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, N.S.; Fernández, I.C.; Duran, L.P.; Venegas-González, A. Community-driven post-fire restoration initiatives in Central Chile: When good intentions are not enough. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Monde. In Bolivia, Behind the Catastrophic Fires, a Race for Agricultural Growth. 5 October 2024. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/environment/article/2024/10/05/in-bolivia-behind-the-catastrophic-fires-a-race-for-agricultural-growth_6728240_114.html (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Sapkota, L.M.; Shrestha, R.P.; Jourdain, D.; Shivakoti, G.P. Factors affecting collective action for forest fire management: A comparative study of community forest user groups in Central Siwalik, Nepal. Environ. Manag. 2015, 55, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, B.; Grzegorz, Z.; Stępnicka, N. Forest fires and losses caused by fires–an economic approach. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2021, 17, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmenta, R.; Parry, L.; Blackburn, A.; Vermeylen, S.; Barlow, J. Understanding human-fire interactions in tropical forest regions: A case for interdisciplinary research across the natural and social sciences. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, R.W.; Lee, B.; Perkins, J.H. Public policies affecting forest fires in the Americas and the Caribbean. FAO For. Pap. 1999, 138, 65–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. A burning story: The role of fire in the history of life. BioScience 2009, 59, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.J.; Keeley, J.E. Fire as a global ‘herbivore’: The ecology and evolution of flammable ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Bilbao, B.A.; Berardi, A. Community owned solutions for fire management in tropical ecosystems: Case studies from Indigenous communities of South America. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. 2016, 371, B37120150174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, S.J. California wildfires signal the arrival of a planetary fire age. Conversation 2019, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pasiecznik, N.; Goldammer, J.G. Towards fire-smart landscapes. Trop. For. Issues 2022, 61, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Pierotti, R.; Wildcat, D. Traditional ecological knowledge: The third alternative (commentary). Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libonati, R.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Da Camara, C.C.; Peres, L.F.; Oom, D.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Silva, J.M.N. Twenty-first century droughts have not increasingly exacerbated fire season severity in the Brazilian Amazon. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J.; García, M.; Yebra, M.; Oliva, P. Satellite Remote Sensing Contributions to Wildland Fire Science and Managemen. Curr. For. Rep. 2020, 6, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpakowski, D.M.; Jensen, J.L. A review of the applications of remote sensing in fire ecology. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M.E.G.; Cabello, A.S.; García, A.S. The Milpero of the Macehual Mayan normative system Vis à Vis with global laws and policies of agricultural fire. In Socio-Environmental Regimes and Local Visions: Transdisciplinary Experiences in Latin America; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

| Question | Colombia (%) | Ecuador (%) | Peru (%) | Bolivia (%) | Andean Community (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | I’m Not Sure | Yes | No | I’m Not Sure | Yes | No | I’m Not Sure | Yes | No | I’m Not Sure | Yes | No | I’m Not Sure | |

| Are you currently engaged in natural resource management, agriculture, firefighting, or environmental protection? | 60 | 40 | 0 | 73.3 | 26.7 | 0 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 | 69.6 | 30.4 | 0 |

| Are you aware that there are specific laws in your country that penalize the unauthorized use of fire, including the illegal burning of forests, vegetation cover, and rural areas? | 80 | 20 | 0 | 93.3 | 6.7 | 0 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 | 79.6 | 20.4 | 0 |

| Did you know that the law includes prison sentences and financial fines for those who burn more than one hectare without a permit? | 60 | 40 | 0 | 86.7 | 13.3 | 0 | 85.7 | 14.3 | 0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 0 | 74.8 | 25.2 | 0 |

| Do you think the current sanctions are sufficient to prevent forest fires? | 40 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 66.7 | 13.3 | 28.6 | 52.4 | 19 | 0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 22.2 | 56.5 | 21.4 |

| Are you aware that in some rural areas of your country, fire is used for traditional agricultural and cultural purposes? | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 0 | 80 | 20 | 0 | 93.8 | 6.2 | 0 |

| Do you believe that current legislation adequately recognizes or takes into account the traditional use of fire in community or rural contexts? | 20 | 80 | 0 | 33.3 | 40 | 26.7 | 14.3 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 25.2 | 49.1 | 25.7 |

| Question | Response Options | Colombia | Ecuador | Peru | Bolivia | Andean Community | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Answered | % Not Answered | % Total | % Answered | % Not Answered | % Total | % Answered | % Not Answered | % Total | % Answered | % Not Answered | % Total | % Answered | % Not Answered | % Total | ||

| Which of the following factors do you believe hinder the enforcement of the law? | Lack of knowledge | 40 | 60 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 47.6 | 52.4 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 53.6 | 46.4 | 100 |

| Limited monitoring | 20 | 80 | 100 | 73.3 | 26.7 | 100 | 47.6 | 52.4 | 100 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 100 | 43.6 | 56.5 | 100 | |

| Institutional weakness | 40 | 60 | 100 | 80 | 20 | 100 | 67.7 | 32.3 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 59.4 | 40.6 | 100 | |

| Local culture of fire use | 60 | 40 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 42.9 | 57.1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 53.2 | 46.8 | 100 | |

| Do you believe that environmental and municipal authorities properly enforce existing regulations on fire prevention and control? | Always | 0 | 100 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 1.7 | 98.3 | 100 |

| Sometimes | 40 | 60 | 100 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 100 | 42.9 | 57.1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 41.6 | 58.5 | 100 | |

| Almost never | 60 | 40 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 47.6 | 52.4 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 46.1 | 53.9 | 100 | |

| Never | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 9.5 | 90.5 | 100 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 100 | 10.7 | 89.3 | 100 | |

| What additional measures would you propose to strengthen forest fire prevention? | Institutional and regulatory strengthening | 10 | 90 | 100 | 30 | 70 | 100 | 25 | 75 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 26.3 | 73.8 | 100 |

| Education, prevention culture, and community work | 50 | 50 | 100 | 25 | 75 | 100 | 30 | 70 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 100 | 28.8 | 71.3 | 100 | |

| Technology, monitoring, and early warning systems | 30 | 70 | 100 | 25 | 75 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 100 | 21.3 | 78.8 | 100 | |

| Integrated landscape management and territorial planning | 10 | 90 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 25 | 75 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 23.8 | 76.3 | 100 | |

| Do you agree that exceptions or differentiated regulations should be established for cultural fire practices? | Yes | 40 | 60 | 100 | 73.3 | 26.7 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 49.2 | 50.8 | 100 |

| No | 20 | 80 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 19 | 81 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 26.4 | 73.6 | 100 | |

| It depends on the context | 40 | 60 | 100 | 26.7 | 73.3 | 100 | 14.3 | 85.7 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 24.4 | 75.6 | 100 | |

| In your experience, to what extent is local knowledge consulted or integrated into the development of forest fire policies in your country? | Frequently | 20 | 80 | 100 | 13.3 | 86.7 | 100 | 4.8 | 95.2 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 9.5 | 90.5 | 100 |

| Occasionally | 20 | 80 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 14.3 | 85.7 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 31.1 | 68.9 | 100 | |

| Rarely | 60 | 40 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 45.9 | 54.2 | 100 | |

| Never | 0 | 100 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 14.3 | 85.7 | 100 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 100 | 13.6 | 86.4 | 100 | |

| Which of the following mechanisms or strategies do you consider necessary to achieve a balance between fire prevention and respect for cultural uses of fire? | Intercultural dialogue and legal recognition of the cultural use of fire | 40 | 60 | 100 | 30 | 70 | 100 | 25 | 75 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 100 | 26.3 | 73.8 | 100 |

| Community training and certification | 25 | 75 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 25 | 75 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 100 | 25.0 | 75.0 | 100 | |

| Zoning and participatory planning | 10 | 90 | 100 | 15 | 85 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 100 | 13.8 | 86.3 | 100 | |

| Technical-cultural education and awareness | 25 | 75 | 100 | 15 | 85 | 100 | 30 | 70 | 100 | 70 | 30 | 100 | 35.0 | 65.0 | 100 | |

| Are you familiar with any of the forest fire policies currently implemented in your country? | Yes | 80 | 20 | 100 | 73.3 | 26.7 | 100 | 61.9 | 38.1 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 58.0 | 42.0 | 100 |

| No | 20 | 80 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 23.8 | 76.2 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 25.1 | 74.9 | 100 | |

| In name only | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 14.3 | 85.7 | 100 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 100 | 16.9 | 83.1 | 100 | |

| Do you consider that these policies are being effectively implemented in your region? | Yes | 0 | 100 | 100 | 13.3 | 86.7 | 100 | 10 | 90 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 5.8 | 94.2 | 100 |

| No | 20 | 80 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 30 | 70 | 100 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 100 | 43.3 | 56.7 | 100 | |

| Partially | 40 | 60 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 45 | 55 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 35.4 | 64.6 | 100 | |

| I don’t know | 40 | 60 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 15 | 85 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 15.4 | 84.6 | 100 | |

| Which of the following aspects do you consider most important for improving the effectiveness of these policies? | Inter-institutional coordination | 100 | 0 | 100 | 86.7 | 13.3 | 100 | 65 | 35 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 75.4 | 24.6 | 100 |

| Financial resources | 60 | 40 | 100 | 80 | 20 | 100 | 45 | 55 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 58.8 | 41.3 | 100 | |

| Community participation | 60 | 40 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 65 | 35 | 100 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 100 | 68.8 | 31.3 | 100 | |

| Local technical capacity | 40 | 60 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 70 | 30 | 100 | 33.4 | 66.6 | 100 | 52.5 | 47.5 | 100 | |

| Should cultural uses of fire be recognized in these policies? | Yes | 40 | 60 | 100 | 93.3 | 6.7 | 100 | 71.4 | 28.6 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 55.4 | 44.7 | 100 |

| No | 20 | 80 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 4.8 | 95.2 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 22.9 | 77.1 | 100 | |

| It depends on the context | 40 | 60 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 23.8 | 76.2 | 100 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 21.8 | 78.2 | 100 | |

| On a scale from 1 to 5, how relevant do you think it is to develop a Regional Andean Agenda for Integrated Fire Management (RAAIFM) within the framework of the Andean Community for comprehensive fire management? | 1 Not at all relevant | 20 | 80 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 10.0 | 90.0 | 100 |

| 2 Slightly relevant | 0 | 100 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 1.7 | 98.3 | 100 | |

| 3 Moderately relevant | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 14.3 | 85.7 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 3.6 | 96.4 | 100 | |

| 4 Relevant | 20 | 80 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 9.5 | 90.5 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 9.1 | 91.0 | 100 | |

| Very relevant | 60 | 40 | 100 | 86.7 | 13.3 | 100 | 76.2 | 23.8 | 100 | 80 | 20 | 100 | 75.7 | 24.3 | 100 | |

| Which of the following components do you consider most urgent in your context for the development of a Regional Andean Agenda for Integrated Fire Management (RAAIFM)? | Fire ecology | 20 | 80 | 100 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 100 | 38.1 | 61.9 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 41.2 | 58.8 | 100 |

| Cultural and Indigenous use of fire | 40 | 60 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 47.6 | 52.4 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 48.6 | 51.4 | 100 | |

| Education and training | 100 | 0 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | |

| Technology and monitoring | 60 | 40 | 100 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 100 | 38.1 | 61.9 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 46.2 | 53.8 | 100 | |

| Restoration and prevention | 60 | 40 | 100 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 100 | 52.4 | 47.6 | 100 | 80 | 20 | 100 | 59.8 | 40.2 | 100 | |

| Regulations and legislation | 40 | 60 | 100 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 100 | 47.6 | 52.4 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 63.6 | 36.4 | 100 | |

| Do you believe that the Regional Andean Agenda for Integrated Fire Management (RAAIFM) should incorporate ancestral knowledge and recognize the role of local and Indigenous communities? | Yes | 40 | 60 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 80 | 20 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 65.0 | 35.0 | 100 |

| No | 40 | 60 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 25.0 | 75.0 | 100 | |

| Partially | 20 | 80 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 10.0 | 90.0 | 100 | |

| What level of implementation do you think this proposal would have in your country or community? | High | 0 | 100 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 42.9 | 57.1 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 30.7 | 69.3 | 100 |

| Medium | 60 | 40 | 100 | 40 | 60 | 100 | 52.4 | 47.6 | 100 | 60 | 40 | 100 | 53.1 | 46.9 | 100 | |

| Low | 40 | 60 | 100 | 6.7 | 93.3 | 100 | 4.8 | 95.2 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 12.9 | 87.1 | 100 | |

| None | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 5.0 | 95.0 | 100 | |

| What elements or approaches do you think should be added or strengthened? | Community participation and multi-level governance | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 100 |

| Community participation and multi-level governance | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 100 | |

| Financing and transparency | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 100 | |

| Scientific research and knowledge exchange | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 100 | |

| Operational strengthening and professionalization | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 75.0 | 25.0 | 100 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correa-Quezada, L.; Carrión-Correa, V.; López, C.; Segura, D.; Carrión-Paladines, V. Towards Integrated Fire Management: Strengthening Forest Fire Legislation and Policies in the Andean Community of Nations. Fire 2025, 8, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070266

Correa-Quezada L, Carrión-Correa V, López C, Segura D, Carrión-Paladines V. Towards Integrated Fire Management: Strengthening Forest Fire Legislation and Policies in the Andean Community of Nations. Fire. 2025; 8(7):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070266

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorrea-Quezada, Liliana, Víctor Carrión-Correa, Carolina López, Daniel Segura, and Vinicio Carrión-Paladines. 2025. "Towards Integrated Fire Management: Strengthening Forest Fire Legislation and Policies in the Andean Community of Nations" Fire 8, no. 7: 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070266

APA StyleCorrea-Quezada, L., Carrión-Correa, V., López, C., Segura, D., & Carrión-Paladines, V. (2025). Towards Integrated Fire Management: Strengthening Forest Fire Legislation and Policies in the Andean Community of Nations. Fire, 8(7), 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8070266