Fire and Rescue Services’ Interaction with Private Forest Owners During Forest Fires in Sweden: The Incident Commanders’ Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

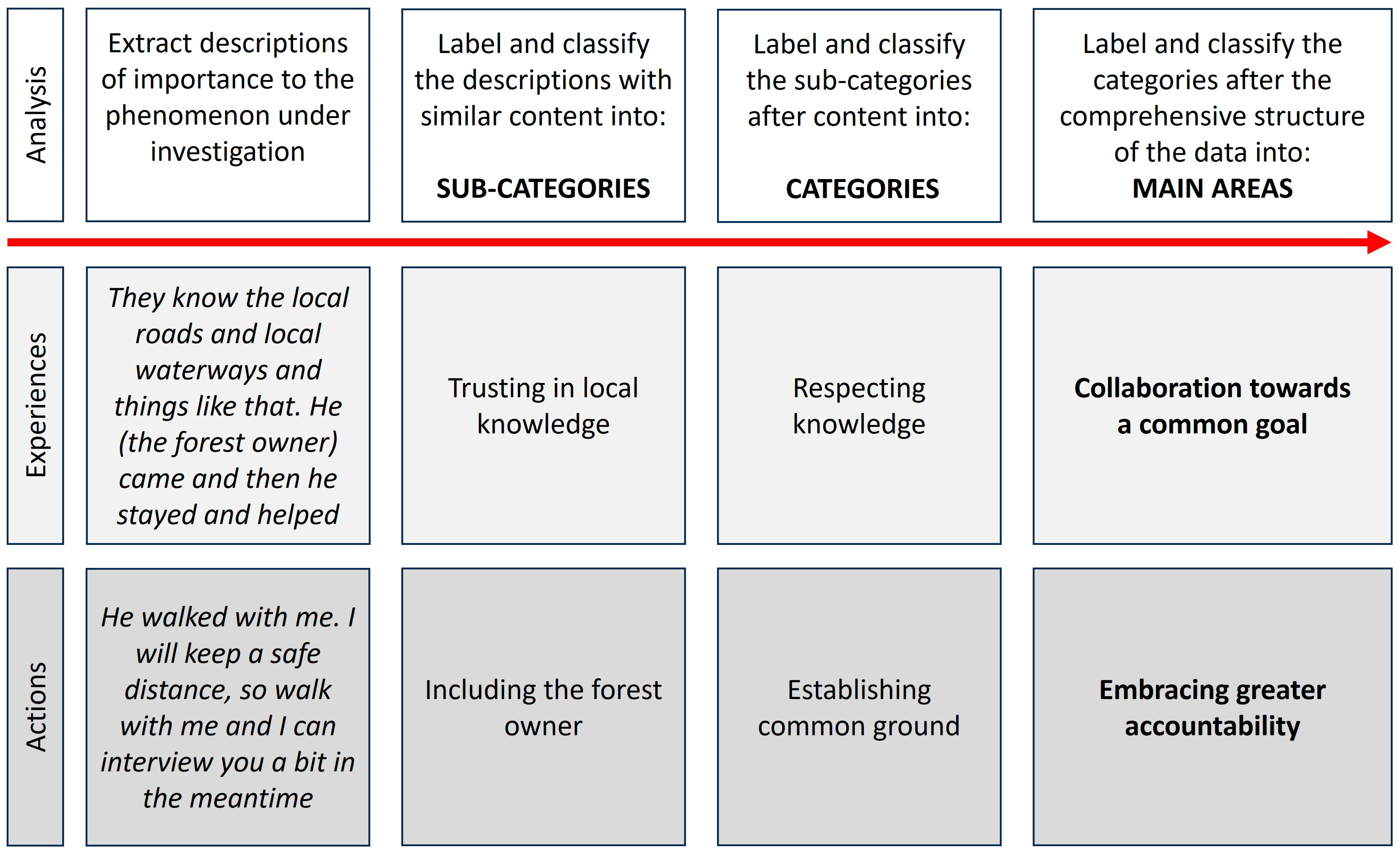

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Experiences

3.1.1. Collaboration Towards a Common Goal

Conveying Trust and Security

“I always feel that it is extremely valuable when I encounter an expert who I can meet and shake hands with. I don’t want to let go of that hand because I will need him.”

“We need all the help we can get, because we don’t have enough people to deal with forest fires. We must have these voluntary resources to support us.”

Respecting Knowledge

“There is such commitment, it doesn’t matter whether you’re an auto mechanic or a manure spreader or whatever, as long as people … as long as we help each other. That was probably the strongest thing for me.”

“We might even be able to work in parallel, so that we can address the area where the fire is still spreading, while the forest owner can focus on monitoring the post-fire area, where the FRS is judged not to be needed. We can work in parallel with each other.”

Addressing Needs

“He doesn’t quite understand at first. He’s afraid that we’ll leave, that he’ll … he envisages that he’ll need a fire truck and hoses. I explain that it’s not the case.”

“I might go out a few days later to talk to the forest owner. And that I can check how he has actually experienced everything.”

“Be humble. Listen to the forest owner … sometimes you might need to be a little flexible with things, to make them work well.”

3.1.2. Mutual Dialogue for Success

Responsibilizing Communication

“But if we fail to disseminate the information and fail to get them to take responsibility, it falls back on us in the end. So, even though we shouldn’t do it, we adapt. The capable ones take over more quickly, while those who lack ability, we assist for longer.”

“We were on the same level. He cared about his forest, and yes, we were working towards the same goal. It was his forest, his property, and his money that disappeared, and I wanted to extinguish this and do my job as well as I could, so we connected quickly and easily.”

Dealing with a Complex Situation

“Then it probably took six hours before I met the other forest owner up there, north of the fire, and by then he had done a lot of things that I wasn’t aware of.”

“It can indeed be positive, but it can also be negative, because it’s a workplace issue in the sense that there’s a risk that people who might not be accustomed to fires end up in the direction of the fire or where there’s smoke that can, quite honestly, lead to loss of life.”

“We FRS personnel underestimate the risk of forest fires, I would say. We drive very close; we go too far on poor roads and think that ‘this will work out’. And the farmers also believe they can handle it.”

“And it’s always difficult, it doesn’t matter if it’s a forest fire or a house fire or whatever it is, to say that it’s extinguished now. It’s among the most challenging things for ICs; they always want some form of continuous monitoring.”

3.2. Actions

3.2.1. Collaborating for the Best Outcome

Creating a Relationship

“We want to get in touch with the forest owner as soon as possible to find out what type of roads there are. What is the accessibility like?”

“Together, we find out where we can obtain forestry machinery so that we can start creating firebreaks, understand what forest is important, and identify which areas we can protect as a last resort, so to speak, and what can actually burn.”

Caring for the Forest Owner

“It is important not ignore [the forest owner]. Even if I assess that there might not be any danger, I still need to show an interest that they are there, because I might also need them.”

“It ended with, well, we’ll continue to monitor [the fire] until it’s out. We let him be old.”

“And perhaps make a call during the evening just to check how things are going. Even though the firefighting phase has passed, there is still … a concern that it shouldn’t flare up again.”

3.2.2. Embracing Greater Accountability

Dealing with Uncertainties

“I’m constantly trying to think about whether he will he have control over this. How will he manage this handover? By asking questions and the more you meet with them, the more a picture emerges of how you think it will go.”

“By allowing the hose to remain, I could ensure that he had water and that he would feel comfortable about the monitoring by allowing the hose to remain”.

Establishing Common Ground

“He actually walked with me. I said that I would keep a safe distance, so he could come with me and I could discuss things with him at the same time.”

“Yes, he was there to support us when we brought out the maps. In this situation, when we presented a worst-case scenario, he was also involved a little in the decisions. He was like my, well, advisor really.”

“I see that within a few hours we can leave in our vehicles. And I explain to the forest owner that we are now activating those who are coming to help with the monitoring.”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Method

4.2. Discussion of Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jolly, W.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; Freeborn, P.H.; Holden, Z.A.; Brown, T.J.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. Wildfires and global change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 19, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Spreading like Wildfire—The Rising Threat of Extraordinary Landscape Fires; UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Boin, A.; Keller, A. Managing Transboundary Crises: Identifying the Building Blocks of an Effective Response System. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2010, 18, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E. Governance Networks in the Public Sector. Erik Hans Klijin and Joop Koppenjan. Routledge, New York, 2016. 360 pp. $65.95 (paper). Governance 2017, 30, 732–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björcman, F.; Nilsson, B.; Elmqvist, C.; Fridlund, B.; Svensson, A. Exploring Swedish forest owners’ and fire and rescue services’ experiences of collaboration during forest fires. In Proceedings of the IUFRO XXVI World Congress of the International Union of Forest Research Organizations, Stockholm, Sweden, 23–29 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Deuffic, P.; Ní Dhubháin, Á. Invisible losses. What a catastrophe does to forest owners’ identity and trust in afforestation programmes. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 60, 104–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdesmäki, M.; Matilainen, A. Born to be a forest owner? An empirical study of the aspects of psychological ownership in the context of inherited forests in Finland. Scand. J. For. Res. 2013, 29, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCB. Statistics Sweden. Statistics Sweden. Markanvändsningsklass och år (Land Use Class and Year). Jordbruksmark och Skogsmark Efter Region och Markanvändningsklass. År 1951–2020. 2023. Available online: https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__MI__MI0803__MI0803A/MarkanvJbSkN/ (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Skogsstyrelsen. Statistiska Meddelanden Fastighets och Ägarstruktur i Skogbruk 2020 (Statistical Notices Property and Ownership Structure in Forestry 2020); Swedish Forest Agency, Ed.; Skogsstyrelsen: Jönköping, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström, J.; Granström, A. Human activity and demographics drive the fire regime in a highly developed European boreal region. Fire Saf. J. 2023, 136, 103743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSO. Lag (2003:778) om Skydd mot Olyckor (Civil Protection Act). 2003. Ikraft: 2004-01-01 Överg.best. 2003. Available online: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2003778-om-skydd-mot-olyckor_sfs-2003-778 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- MSB. Förslag Strategi och Handlingsplan Deltidsbrandman (Proposal Strategy and Action Plan Part-Time Firefighter). Available online: https://www.msb.se/contentassets/6cc0a8c1cfdd42bba778dce88e0c7a97/forslag-strategi-och-handlingsplan-deltidsbrandman.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Lovtidend, N. Forskrift om Organisering, Bemanning og Utrustning av Brann- og Redningsvesen og Nødmeldesentralene (Brann- og Redningsvesenforskriften). Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2021-09-15-2755 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Svensson, S. Command and Control of Fire and Rescue Operations in Sweden. In Fire and Rescue Services: Leadership and Management Perspectives; Murphy, P., Greenhalgh, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rake, E.L.; Njå, O. Perceptions and performances of experienced incident commanders. J. Risk Res. 2009, 12, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dynes, R.R.; Quarantelli, E.L.; Kreps, G.A. A Perspective on Disaster Planning, 3rd ed.; REPORT SERIES #11; University of Delaware Disaster Research Center: Newark, DE, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Daddoust, L.; Asgary, A.; McBey, K.J.; Elliott, S.; Normand, A. Spontaneous volunteer coordination during disasters and emergencies: Opportunities, challenges, and risks. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 65, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J.; McLennan, B.; Handmer, J. A review of informal volunteerism in emergencies and disasters: Definition, opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 13, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidskog, R. Invented Communities and Social Vulnerability: The Local Post-Disaster Dynamics of Extreme Environmental Events. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidskog, R.; Sjödin, D. Extreme events and climate change: The post-disaster dynamics of forest fires and forest storms in Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 2015, 31, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Kooistra, C.; Hall, T.; Pickering, M. Understanding the Effect of Large Wildfires on Residents’ Well-Being: What Factors Influence Wildfire Impact? For. Sci. 2016, 62, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö.; Nohrstedt, D. Formation and performance of collaborative disaster management networks: Evidence from a Swedish wildfire response. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 41, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.C. The Critical Incident Technique. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 51, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridlund, B.; Henricson, M.; Mårtensson, J. Critical Incident Technique applied in nursing and healthcare sciences. SOJ Nurs. Health Care 2017, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCB. Statistics Sweden. Sveriges Befolkning. Available online: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/manniskorna-i-sverige/sveriges-befolkning (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Skogsstyrelsen. Fastighets och Ägarstruktur i Skogsbruket 2021 (Property and Ownership Structure in Forestry in 2021); Swedish Forest Agency, Ed.; Produktnummer: JO1405; Serie: JO—Jordbruk, Skogsbruk och Fiske; Skogsstyrelsen: Jönköping, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gobo, G. Qualitative Research Practice. Sampling, Representativeness and Generalizability; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 435–456. [Google Scholar]

- WMA. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Reserch Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Epistomological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiery. ECTJ 1982, 30, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, P.; Barnett, T.; Woodroffe, J. Critical Incident Technique—A Useful Method for the Paramedic Researcher’s Toolkit. Australas. J. Paramed. 2015, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselqvist-Ax, I.; Nordberg, P.; Svensson, L.; Hollenberg, J.; Joelsson-Alm, E. Experiences among firefighters and police officers of responding to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in a dual dispatch programme in Sweden: An interview study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kete, S. Local community participation and volunteerism in wildfire area management: A systematic review. Turk. J. For.|Türkiye Orman. Derg. 2023, 24, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, M.; Sydnes, M.; Sydnes, A.K. Integrating unorganized volunteers in emergency response management. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2016, 5, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, M.L. Stop!!!!! Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2010, 25, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SOU. Skogsbranderna Sommaren 2018 (The Forest Fires in the Summer of 2018); Swedish Government Official Reports, Ed.; Regeringskansliet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, L.M.; Catlett, C.; Tosatto, R.; Kirsch, T.D. The utility of and risks associated with the use of spontaneous volunteers in disaster response: A survey. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2014, 8, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, S.; Yumagulova, L.; Mackwani, Z.; Benson, C.; Stone, J.T. Canadian citizens volunteering in disasters: From emergence to networked governance. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2017, 26, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Ryan, B.; Bearman, C.; Toh, K. Should We Leave Now? Behavioral Factors in Evacuation Under Wildfire Threat. Fire Technol. 2018, 55, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogsforsk. Avslutande av insats ot skogsbrand. In Räddningsledarens Checklista; Skogsforsk: Ljungby, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey, S.; Toman, E.; Stidham, M.; Shindler, B. Social science research related to wildfire management: An overview of recent findings and future research needs. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2013, 22, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhnoo, S.; Persson, S. Emotion management of disaster volunteers: The delicate balance between control and recognition. Emot. Soc. 2020, 2, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.A.; Miller, L.F.; Greiner, S.M.; Kooistra, C. A Qualitative Study on the US Forest Service’s Risk Management Assistance Efforts to Improve Wildfire Decision-Making. Forests 2021, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Understanding spontaneous volunteering in crisis: Towards a needs-based approach of explanation. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.S.; Higgins, L.L.; Cohn, P.J.; Burchfield, J. Community Wildfire Events as a Source of Social Conflict. Rural. Sociol. 2006, 71, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vylund, L.; Frykmer, T.; McNamee, M.; Eriksson, K. Understanding Fire and Rescue Service Practices Through Problems and Problem-Solving Networks: An Analysis of a Critical Incident. Fire Technol. 2024, 60, 3475–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lyu, S. Public Participation in Wildfire Rescue and Management: A Case Study from Chongqing, China. Fire 2024, 7, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, V.; Adamis, D.; Mellon, R.C.; Prodromitis, G.; Kyriopoulos, J. Trust, Social and Personal Attitudes after Wildfires in a Rural Region of Greece. Sociol. Mind 2012, 2, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, E.A.; Thwaites, R.; Curtis, A.; Millar, J. Factors affecting community-agency trust before, during and after a wildfire: An Australian case study. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 130, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toman, E.; Stidham, M.; McCaffrey, S.; Shindler, B. Social Science at the Wildland-Urban Interface: A Compendium of Research Results to Create Fire-Adapted Communities; Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-111; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2013; 75p.

- Uhnoo, S.; Hansen Löfstrand, C. Voluntary policing in Sweden: Media reports of contemporary forms of police–citizen partnerships. J. Scand. Stud. Criminol. Crime Prev. 2018, 19, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MissingPeople. Om Missing Peolpe Sweden. Available online: https://www.missingpeople.se/om-oss/ (accessed on 17 May 2024).

| Gender | Number of Participants |

| Male | 19 |

| Female | 3 |

| Age | Years |

| Youngest | 31 |

| Oldest | 62 |

| Years Working in the Role of IC | Years |

| ≤10 | 5 |

| 11–20 | 12 |

| ≥21 | 5 |

| Number of Forest Fires in the Role of IC | Number of Participants |

| ≤10 | 8 |

| 11–20 | 4 |

| ≥21 | 10 |

| Interview Questions | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Where did you meet the forest owner? |

| 2 | Can you describe it to me in detail? |

| 3 | Why do you remember this particular occasion? |

| 4 | What did you do when you talked to each other? |

| 5 | What was your attitude/mood like? |

| 6 | What were you thinking during and after you finished your communication? |

| 7 | How did you feel during and after your meeting? |

| 8 | What were the most demanding aspects of the meeting with the forest owner? |

| 9 | What does the event mean to you in retrospect? |

| Sub-Category (n) | Category | Main Area |

|---|---|---|

| Comforting knowledge (34) | Conveying trust and security | Collaboration towards a common goal |

| Feeling safe with the forest owner (17) | ||

| Relieving network (35) | ||

| Feeling safe with external resources (27) | ||

| Prioritizing contact (16) | Respecting knowledge | |

| Experiencing a positive meeting (25) | ||

| Including the forest owner (15) | ||

| Trusting in local knowledge (19) | ||

| Seeing the forest owner’s worries (27) | Addressing needs | |

| Caring for the forest owner (24) | ||

| Assisting with responsibility (18) | ||

| Being calm (16) | Responsibilizing communication | Mutual dialogue for success |

| Creating understanding (20) | ||

| Benefiting from mutual dialogue (18) | ||

| Seeing the common goal (14) | ||

| Reaching mutual understanding (24) | ||

| Handling unpredictable aspects (17) | Dealing with a complex situation | |

| Worrying about the forest owner (10) | ||

| Feeling inadequate (9) | ||

| Frustrating dialogue (30) | ||

| Making the right decision (10) |

| Sub-Category (n) | Category | Main Area |

|---|---|---|

| Contacting the forest owner (23) | Creating a relationship | Collaborating for the best outcome |

| Asking about the area (15) | ||

| Asking for help (9) | ||

| Accepting help (7) | ||

| Convey security and control (16) | Caring for the forest owner | |

| Acting with care (17) | ||

| Prolonging contact (16) | ||

| Avoiding misunderstanding (28) | Dealing with uncertainties | Embracing greater accountability |

| Planning ahead (18) | ||

| Leaving resources (10) | ||

| Reaching out with information (7) | Establishing common ground | |

| Including the forest owner (19) | ||

| Including through practical work (11) | ||

| Discussing a common picture (19) | ||

| Encouraging networking (12) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Björcman, F.; Nilsson, B.; Elmqvist, C.; Fridlund, B.; Blom, Å.R.; Svensson, A. Fire and Rescue Services’ Interaction with Private Forest Owners During Forest Fires in Sweden: The Incident Commanders’ Perspective. Fire 2024, 7, 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7120425

Björcman F, Nilsson B, Elmqvist C, Fridlund B, Blom ÅR, Svensson A. Fire and Rescue Services’ Interaction with Private Forest Owners During Forest Fires in Sweden: The Incident Commanders’ Perspective. Fire. 2024; 7(12):425. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7120425

Chicago/Turabian StyleBjörcman, Frida, Bengt Nilsson, Carina Elmqvist, Bengt Fridlund, Åsa Rydell Blom, and Anders Svensson. 2024. "Fire and Rescue Services’ Interaction with Private Forest Owners During Forest Fires in Sweden: The Incident Commanders’ Perspective" Fire 7, no. 12: 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7120425

APA StyleBjörcman, F., Nilsson, B., Elmqvist, C., Fridlund, B., Blom, Å. R., & Svensson, A. (2024). Fire and Rescue Services’ Interaction with Private Forest Owners During Forest Fires in Sweden: The Incident Commanders’ Perspective. Fire, 7(12), 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire7120425