Abstract

Working in high consequence yet low frequency, events Australian fire service Incident Controllers are required to make critical decisions with limited information in time-poor environments, whilst balancing competing priorities and pressures, to successfully solve dynamic large-scale disaster situations involving dozens of personnel within the Incident Management Team, including of front-line responders from multiple jurisdictions. They must also do this within the boundaries of public and political expectations, industrial agreements, and the legal requirement to maintain a safe workplace for all workers, inclusive of volunteers. In addition to these operational objectives, fire services must also provide realistic training to prepare frontline staff, whilst satisfying legislative requirements to provide a safe workplace under legislation that does not distinguish between emergency services and routine business contexts. In order to explore this challenge, in this article we review the different safety standards expected through industrial and legal lenses, and contextualize the results to the firefighting environment in Australia. Whilst an academic argument may be presented that firefighting is a reasonably unique workplace which exposes workers to a higher level of harm than many other workplaces, and that certain levels of firefighter injury and even fatality are acceptable, no exception or distinction is provided for the firefighting context within the relevant safety legislation. Until such time that fire services adopt the legal interpretations and applications and develop true safety management systems as opposed to relying on “dynamic risk assessment” as a defendable position, the ability of fire services and individual Incident Controllers to demonstrate they have managed risk as so far as reasonably practicable will remain ultimately problematic from a legal perspective.

1. Introduction

Incident Controllers within the Australian fire services context are the individuals ultimately in command of the immediate response and recovery relief to natural and human caused disasters including but not limited to fire, hazardous materials, cyclone, and flood [1]. Working in high consequence yet low frequency events, they are required to make critical decisions with limited information in time-poor environments [2,3,4,5]. Within such high-pressure contexts, Incident Controllers must be able to balance competing priorities and pressures to successfully direct the resolution of dynamic large-scale disaster situations active 24 h a day, lasting weeks and involving dozens of personnel within the Incident Management Team, including hundreds of front-line responders from multiple jurisdictions. They must also do this within the boundaries of public and political expectation, industrial agreements, and the legal requirement to maintain a safe workplace for all workers, inclusive of volunteers [6].

During emergency response, where there is an actual or impending threat to life, the threshold of risk tolerance by firefighters and Incident Controllers is higher than that of most other workplaces [7,8,9]. In other words, the higher threat to the life and safety of firefighters during a structure fire where children require rescuing is acceptable compared to the acceptable level of threat to the life and safety of an accountant, dentist, teacher, etc. in their respective workplace. Notwithstanding this comparison, failure to correctly manage disaster related risk to the standard required, either by failure to comprehend the full nature of risk, or by incorrectly applying a risk framework, may unintentionally worsen rather than reduce adverse consequences. This, in turn, can contribute to firefighter injuries and fatalities, reputational damage, significant operational disruption and even litigation [10,11], not only negatively impacting the staff involved, but also the public confidence in controlling agencies.

At the same time, frontline firefighters operating under the command of Incident Controllers require realistic training so that they can safely respond as part of coordinated and high performing teams to dangerous situations. Unlike actual emergencies, however, these training environments do not involve any actual threat to life or persons being in danger. The need to provide realistic training scenarios in order to adequately prepare trainee firefighters for emergency situations needs to be carefully balanced with the legal requirement to provide a safe workplace where no emergency exists. Complex scenarios where this applies include emergency response driving, internal structural firefighting operations (that is when firefighters suppress a burning building from within the impacted structure itself and try to rescue occupants at the very limits of human tenability), and training for entrapment and burnover during wildfire fighting operations. As a simple example that allows examination in more detail, during emergency response to structure fires that threaten the life of civilians, firefighters can be required to climb ladders and perform a “leg lock” manoeuvre mid ascent which involves them using their legs to lock onto the ladder and remove their hands in order to secure firefighting hose to the ladder using “hooks”. This manoeuvre, as with all ladder operations, is conducted in the “heat of battle” with the firefighter in full Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and potentially wearing self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), both weighing upwards of a combined 20 to 30 kg and restricting both vision and movement, and without harness or fall arrest devices due to the nature of the response conducted in the absence of any usable anchoring points. By nature of the circumstances of the emergency response, such work methods and risks to firefighters are considered acceptable by some Incident Controllers, even if a nominal number of firefighter injuries or even fatalities occur each year [9].

In the training environment, novice trainee firefighters must learn how to safely perform these and other critical tasks so that they can replicate them under time-poor emergency conditions. The difference in the training environment, however, is that the tolerance to firefighter injury, let alone firefighter fatality, is significantly lower. For example, a fire service’s low tolerance for trainee injury (regardless of actual rates of occurrence) may result in procedures requiring trainees to wear fall arrest devices when learning and practicing ladder skills. During actual emergencies, however, no such requirement exists and the potential for firefighter fall injuries or even fatalities when working on ladders is tolerated. This variance in risk tolerance results in novice firefighters performing dangerous working at heights operations without fall arrest devices or safety harnesses for the first time during life threatening emergencies where they may “fall back to the level of their training”.

Balancing fire service operations goals of effective emergency response and providing realistic training, with legislative requirements to provide a safe workplace under legislation that does not distinguish between the nature of different workplaces is inherently challenging. The complexity of achieving this balance is further increased when significant changes are made to the legislative environment, such as the introduction of the new work health and safety legislation that both redefines the rules of engagement, and significantly increases the potential consequences for supervising individuals and corporate officers. In Western Australia, for example, under recently introduced legislation, individual failure to achieve the required standard of care, causing death or serious injury, can result in penalties up to and including a term of imprisonment of 5 years [12]. We hypothesise that these collective circumstances have resulted in critical disruption between the understanding and expectations of the legislators and fire services and the legislators and Incident Controllers. In turn, we posit that this may lead to consequences ranging from reduced or inappropriate safety performance at incidents, to inappropriate training that fails to adequately prepare responders for the dangers of actual emergencies and disasters, and potentially through to the more extreme outcomes of discouraging high performing officers from committing to Incident Controller roles out of fear of being held personally liable for firefighter injuries and other safety-related consequences that occur during dynamic and dangerous emergencies, as a result of legislation that applies the same standard expectation for safety regardless of whether the incident occurs in an accounting, construction or emergency environment.

In order to quantify and address the extent by which the safety-related rules of engagement have changed for Australian fire services, in this study we (1) conduct a literature review to explore competing definitions and expectations of the standard of care required through industrial and legal perspectives, (2) contextualise the results to the firefighting environment, and (3) discuss the implications on large-scale incident disaster management. In doing so, we seek to provide guidance regarding the rules by which fire service personnel must operate, reducing decision-making uncertainty and ultimately improving the standard of emergency response in the most critical of contexts. This review study is novel in that it is the first to analyse this complex problem and is innovative in that it seeks to guide emergent practice that extends well beyond the Australian context. Whilst workplace health and safety laws inevitably vary between countries, the presented analysis and findings of the study may well guide improvements in the working relationship between fire services and safety legislation internationally.

2. Materials and Methods

Even within the corporate context far removed from emergency management, it is difficult for academics and practitioners alike to keep up with transformational changes [13]. Within the dynamic high-consequence field of disaster management, this becomes even more challenging, particularly where the rules of engagement from a political or legal perspective shift significantly. In such cases, literature reviews can assist by providing a synthetised overview of knowledge from disciplines that are disparate and interdisciplinary [13]. As such, a literature review is selected for this study, which seeks to provide a synthesised overview of the standard of care within the fire services operations, and legislative frameworks.

As the purpose of the study is to synthetise and contrast perspectives from specific topics, as opposed to providing a systematic review of all of the literature related to a single topic, an integrative review methodology is applied in the study [13]. Whilst integrative reviews can support conceptual advances [14] and new perspectives to emerge [15], including the one sought in this study, they are not without their limitations. Lacking the structured process of a systematic literature review, integrative reviews require a higher level of expertise and research experience within the research team, as there is less supportive guidance regarding appropriate research steps and rigor [15]. In an effort to provide the level of expertise required to both conduct a rigorous study and to correctly interpret industry-specific documentation, the research team for the study deliberately sought a balance of both academic and industry knowledge. The team subsequently included a combination of a fire services incident controller (G.P.), academics (G.P. and M.C.), a former industry regulator inspector (S.R.), and a lawyer specialising in workplace health and safety (G.S.), with a collective two PhDs (G.P. and M.C.) and multiple peer-reviewed academic publications in relevant fields.

To provide the required level of scientific rigor to the study, the study design adopted the four phases recommended by [13]:

- Designing the review: for the reasons discussed above, an integrative review was selected.

- Conducting the review: English-language industry and regulatory guidance published by government or government-recognised industry safety and regulatory bodies; fire services; peer-reviewed and published academia; and current legislation and legal precedent pertaining to Australian workplace health and safety was identified through data base (including Westlaw, Law Journal Library, and Informit) and hand searching. Australian industry and government documentation was found through hand searching. References were scanned for additional suitable inclusions. Acknowledging the study is not a Systematic Literature Review, search terms included “legislation, workplace health and safety, as low as reasonably practicable, as so far as reasonably practicable, standard of care, and firefighting” as well as relevant derivatives of each term. Whilst the age of current legislation and precedents prevented the adoption of a set publication date range (legislation and precedent both remaining current regardless of the date of publication until otherwise rescinded or superseded), only current legislative and industry documentation was included in the study.

- Analysis: Adopting a similar approach to House et al. [16], specific lines of inquiry were applied:

- Industry and academic approaches, capturing the traditional principles of Australian workplace health and safety, most notably the principle of “As Low As Reasonably Practicable” or ALARP.

- Legal statute and case law, capturing the statutes and legal precedent establishing the workplace health and safety standard of care.

The use of these lines of inquiry enabled the authors to distill the information collected during the review, a methodology that assists the operator to make sense of, and gain situational awareness in unfamiliar environments [17].

- 4.

- Writing the review: to provide a structured and meaningful narrative, the study is presented using the lines of enquiry identified above. The paper is subsequently structured as follows:

- Section 3 firstly reports on industry and academic approaches including a detailed examination of the concept and determination of ALARP, and secondly describes the legal perspective and its application to industries including fire services.

- Section 4 provides the discussion or synthesis of findings with particular relevance and application to current fire services operations.

- Section 5 acknowledges the limitations of the current study and suggests areas for future research.

- Section 6 presents the conclusion of the study.

3. Results

3.1. Industry and Academic Approaches

Traditionally, the general principles of Australian workplace health and safety theory have been based upon the United Kingdom’s Robens-style legislation that has been widely adopted across Australian jurisdictions since the early 1980s and further developed by successive reviews [18]. Within this context, a hazard is defined as a situation or thing that could lead to injury or loss, and risk is expressed as the combination of the likelihood of an event occurring and a particular consequence being realised as a result [9,19], and potential injury or loss actually occurring. It should be noted that ISO31000 Risk management principles and guidelines defines risk as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” [19]. It follows that, to ensure that a hazard does not lead to a harmful incident, an actor in any given environment must understand the full nature of the hazards that they are required to be managed and the available control measures that would effectively manage the associated risks.

Organisations are required to implement a risk-based approach to eliminate or minimise risks to create a safe workplace [20]. Where risks cannot be managed to a broadly acceptable level, they may be tolerated if they are reduced to “as low as reasonably practicable” or ALARP [21], noting the terms “practicable”, “so far as is reasonably practicable” and “ALARP” are at times used interchangeably within the Australian context, with ALARP being the most commonly accepted term within industry and academic contexts [20,21,22,23,24]. The ALARP principle requires that all effective safeguards, including best practices, which could be implemented without disproportionate cost or risk (those that are reasonably practicable), are implemented [22]. Such processes are used in many different arenas; however, the term ALARP may not be so commonly used.

For example, in the financial world, investments are typically characterised by their “risks”, particularly in areas such as superannuation [25]. Investors are given multiple options that cater for varying risk appetites; a retiree would often achieve ALARP by investing in a “cash” option, whereas a younger individual may be attracted by a riskier “growth” option. This example illustrates the relationship between risk appetite and ALARP in a financial setting. When considering occupational health and safety risks, developing an appetite for increased risk in a traditional workplace (for example, construction, dentistry, architecture) is obviously something that should be avoided and the principle of ALARP should be strictly adhered to and high-risk work will require the implementation of high-level safeguards to prevent harm. From a fire services perspective, where the environment is inherently more dynamic and complex, and potential consequences can include the loss of multiple lves as opposed to a reduction in stock price, the agreement as to the tolerable level of risk and the definition of ALARP is inherently problematic [9].

In order to define ALARP in any given situation, it is essential that the hazards and the accompanying risks are well understood, as well as the full character of the control measures that are available. In mature risk management processes, for example fire safety engineering or dam construction and safety engineering, robust data may support ALARP being defined by both acceptable probability of risk to life, and by documented grossly disproportionate cost factors. In areas of greater uncertainty, however, the attainment of ALARP requires significantly more consideration, especially within the fire services context where the timeframe with which to make sound decisions can be minimal [4,5,9].

3.1.1. The Principle of ALARP

Whilst the legal concept of “reasonably practicable” is evident within judgements in the late 1940s and early 1950s [26,27], the principle of ALARP originates from the United Kingdom Health and Safety Executive [21] framework for tolerability of risk. Despite this being embedded in other industries, it remains largely unexplored from a fire services perspective [9]. ALARP considers practicality; in other words, can something be done, what are the cost and benefits of action, and is it worth doing something in the circumstances? [20,21,22,23,24] The concept of ALARP provides three risk tolerance categories, defined by two thresholds or criteria:

- ALARP has not been demonstrated and risk is unacceptable;

- Risk is tolerable if ALARP is comprehensively demonstrated; and

- Level of risk is broadly acceptable and can be managed, so far as is reasonably practicable, through continuous improvement.

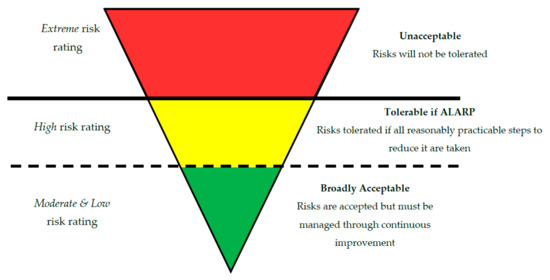

Typical risk heat maps identify Extreme risks as unacceptable, High risks as undesirable, Moderates risk as requiring monitoring and Low risks as acceptable. This means no Extreme risks are tolerable within the organisation. High risks can only be tolerated as long as they have been mitigated as low as reasonably practicable (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ALARP risk tolerance categories.

In the absence of an industry standard within the firefighting context [9], other industries including oil and gas, heavy industry, construction, and mining were examined to provide guidance. A consistent position particularly across these industries and their regulators [20,21,24,28,29], is that risks may be considered ALARP if (1) they are tolerable; and (2) it is demonstrated that the cost of implementation of any further or alternative risk control measure is grossly disproportionate to the suitably weighted risk avoidance benefit.

Determining what is “reasonably practicable” must be completed objectively, in other words it means that the risk owner or other duty holder must meet the standard of behaviour expected of a reasonable person in that position [20,23,30]. The knowledge about a hazard or risk, and any ways of eliminating or minimising the hazard or risk, will be what the duty holder actually knows, and what a reasonable person in the duty holder’s position (e.g., a person in the same industry) would reasonably be expected to know. A risk owner/duty holder can gain this knowledge in various ways, for example, by consulting stakeholders; considering relevant organisational policies and guidelines; undertaking risk assessments; analysing previous incidents; and considering relevant regulations, Codes of Practice, guidelines and published literature. There is no guarantee that a court (civil or criminal) or external assessment will agree with a duty holder’s determination of what is “reasonably practicable”; however, it is more probable that the duty holder’s determination will be viewed favourably if a process of justified decision-making is adhered to [10]. The ability to demonstrate a justifiable decision-making process becomes even more important in fire and emergency services contexts where the ability for fellow fire services personnel, or a court, to “after-the-fact” comprehend the complex and at times near instantaneous sense-making and plan formation processes of an Incident Controller during dynamic emergency response [17] can be challenging.

The determination of what is reasonably practicable is made without reference to the duty holder’s capacity to pay for the required controls [28,29]. Table 1 provides guidance as to what may be considered a relevant matter from an industry regulator perspective when assessing what is reasonably practicable. It is considered that if a duty holder cannot afford to implement a reasonably practicable risk control, the duty holder should not engage in the activity that gives rise to that hazard or risk. The cost associated with the control measures required a further reduction in the likelihood or consequences, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk. If the cost of implementing the control is disproportionate to the benefit gained, then it is not reasonably practicable to implement that control. In the context of fire services emergency response, the incident controller must often view the cost not in terms of AUD expended, but in terms of lives saved and lives lost [4,5,7]. In certain situations, this extends to considerations of how many firefighters” lives can be “spent” in order to save casualties during the most dangerous of emergencies and disasters [9].

Table 1.

The relevance of risk factors that may be considered during by regulators or by external parties (adapted from ([11], p. 5) under a Creative Commons license).

Although the cost of mitigating risk is relevant in determining what is reasonably practicable, safety must remain the highest priority. Adopting a conservative approach, any Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) should be undertaken after the extent of the risk and the control measures are determined [22]. When calculating actual costs of implementing a control measure, any cost savings arising from its implementation must also be considered. For example, the costs of purchase, installation and maintenance of a control measure should be considered alongside the cost benefits of fewer injuries, less reputational damage and other business savings. When calculating the benefit of the risk reduction, both the inherent and residual risk should be considered. The difference in risk over the life of the control is known as the “safety benefit”. From a firefighting perspective, this is further complicated by differing risk tolerances between Incident Controllers and firefighters, whereby individual firefighters are more likely to accept the possibility of personal injury or death when completing rescues compared to the Incident Controller who is required to commit them into such situations [9]. Inevitably, in a fire services context, the reduction in risk to firefighting personnel such as adopting a defensive external strategy at a structure fire may likely lead to increased risk of serious injury or death to people trapped inside that structure.

Although the cost of mitigating risk is relevant in determining what is reasonably practicable, safety must remain the highest priority. Adopting a conservative approach, any Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) should be undertaken after the extent of the risk and the control measures are determined. When calculating actual costs of implementing a control measure, any cost savings arising from its implementation must also be considered. For example, the costs of purchase, installation and maintenance of a control measure should be considered alongside the cost benefits of fewer injuries, less reputational damage and other business savings. When calculating the benefit of the risk reduction, both the inherent and residual risk should be considered. As previously stated, the difference in risk over the life of the control is known as the “safety benefit”.

The cost of a human life is known as the “Value of Statistical Life”. According to the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet [31] the Value of Statistical Life in Australia is AUD 4.9 million in 2019. When considering whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the benefits, the Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator [29] identifies that while there is no precise definition of “Gross Disproportion Factor” in Australian law, it is suggested that a factor of 3 was applied for workers and a factor of between 2 (for low risk) and 10 (for high risk) was applied to the public. Based purely on the factors assigned to workers (i.e., firefighters) and the public, the “cost” of one member of the public may hypothetically be deemed to be equivalent to up to three firefighters” lives. Arguably, from a fire services perspective, where an Incident Controller may be faced with a decision that leads to the loss of life of firefighters, but the rescue of members of the public, this approach may be considered of little benefit if not callous.

Within industries outside the fire and emergency context services, an argument may be put forward that, for reasons such as the short remaining life of an asset, the reinstatement cost of a previously functioning risk reduction measure is grossly disproportionate to the risk benefit that it would achieve. This is commonly called reverse ALARP. In this case, the test of best practice must still be met and, since the risk reduction measure was initially installed, it must constitute best practice to reinstall or repair it. Reverse ALARP arguments may not always be considered appropriate in ALARP demonstrations [29]. This does not prevent a suitably justified decision not to reinstate a risk reduction measure if the original reason for installing it changes.

If the risk is still “high”, then additional controls must be implemented to reduce it further, or it must be demonstrated that implementing further corrective actions is grossly disproportionate to the benefit gained.

Determining whether the identified treatments are grossly disproportional is calculated using:

- AUD value assigned to the consequence (e.g., loss of life, reputational damage, civil suit payouts);

- Gross Disproportionate Factor (GDF);

- Cost of the corrective action.

If A × B > C, in other words, if the cost of the corrective action (i.e., the treatment) is less than the cost of the consequences multiplied by the GDF, then the cost of treatment is not disproportionate to the reduction in risk and the treatment must be implemented. If A × B < C, in other words, the cost of the corrective action (i.e., the treatment) exceeds the costs of the consequences multiplied by the GDF, then the cost of the treatment may be considered grossly disproportionate to the benefit gained. Referring back to the previous example using solely the Value of Statistical Life in the firefighting context, applying this approach, a hypothetical argument may be presented that a firefighting operation resulting in the loss of 10 firefighters but resulting in the saving of four civilians can be expressed as:

- AUD value assigned to the consequence is 4 × 4.9 = AUD 19.6 million;

- Gross Disproportionate Factor (GDF) is 10;

- Cost of the corrective action is 10 × 4.9 × 3 = AUD 147 million

Therefore, A × B is AUD 196 million, which is greater than C at AUD 147 million and the cost of the treatment is considered not disproportionate to the outcome. The authors stress that this example is purely an academic exercise only, and should not be considered an endorsement of its application to the fire services context in any way. To apply it without further consideration would indeed contradict the principles of fire service Incident Controller decision-making detailed in [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

3.1.2. Demonstration of ALARP

The degree and rigour required to demonstrate that ALARP has been achieved is commensurate with the level of risk. For example, where potential consequences are minor or insignificant, then a qualitative assessment may be suitable, whereas a risk involving a major or catastrophic consequence, particularly where human life is involved may use quantitative engineering risk assessment incorporating Expected Risk to Life (ERL) and Cost Benefit Analysis.

There is no prescribed methodology for demonstrating ALARP in all situations. Prior to selecting the correct approach, industry requirements must be considered, a task complicated in the fire services where our research suggests no such standard exists. Within established industries, for example the hazardous materials industry, the West Australian Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety [20,23] recognises three assessment techniques for risk-related decision-making for Major Hazard Facilities, which are best practice, engineering risk assessment, and a precautionary approach. For significant and elevated risks, a “Well-Rounded Argument” may be required to construct a legally sound demonstration of ALARP [10]. Where detailed analysis and demonstration are required, a combination of approaches is recommended. For simple operational tasks where mature risk management processes and policies already apply that meet all regulatory safety requirements, a permit/hazard assessment may be sufficient (such as a correctly completed Confined Space Hazard Assessment and Work Permit). In all instances, relevant legislation should be considered when determining what is reasonably practicable. From a fire services perspective, as previously discussed in this paper, and as is consistent with previous research [9], demonstration of appropriate risk management principles including the attainment of ALARP is inherently difficult within a dynamic emergency context.

When assessing whether a decision is justified, considering the concepts of Best Practice, Precautionary Approach and Well-Rounded Argument may be of benefit. In each case, the accepted method should be documented and justified.

Best practice not only means adhering to all regulatory requirements but also means adopting sound engineering design principles, and good operating and maintenance practices. The use of best practice at the design stage is essential to demonstrate achievement of ALARP. This should include use of sound design principles (e.g., inherent safety), codes, standards and guidance. Any operator relying on compliance with codes or standards for the demonstration should:

- Show that a full gap analysis has been carried out;

- Justify any gaps, if found;

- Explain fully why it is not reasonably practicable to further reduce the risk of:

- –

- the highest consequence scenario;

- –

- the most likely (or most frequent) initiating hazard;

- –

- any other scenarios where incidents have been known to occur.

In applying modern standards to old assets, a gross disproportionality argument (for the risk control measures identified during the gap assessment) may be appropriate to demonstrate doing less than modern authoritative best practice.

A precautionary approach replaces engineering uncertainty analysis by adopting conservative assumptions. It should be used if all available engineering and scientific evidence is inconclusive. This approach should be commensurated with the level of uncertainty in the assessment and the possible danger. The hazards that are assessed should include the worst-case scenario that can be realised, but not hypothetical hazards with no evidence that they may occur. While the approach adopted is expected to be proportionate and consistent, safety is expected to take precedence over economic considerations, meaning that a safety measure is more likely to be implemented. In this context, the decision could have significant economic consequences to an organisation in conjunction with the safety implications.

A precautionary approach may result in the implementation of risk reduction measures for which the cost may appear to be grossly disproportionate to the safety benefit gained. However, in these circumstances, the uncertainty associated with the risk assessment means that the risks associated with non-implementation cannot be shown to be ALARP with sufficient certainty.

Miller [10] suggests that a Well-Rounded Argument (WRA) may act as a bridge between the legal requirements and the technical analyses. It is intended to be a summary of all available evidence and any relevant studies to demonstrate that, so far as is reasonably practicable:

- The foreseeable hazards have been identified for all stages of the lifecycle;

- The foreseeable consequences are understood;

- Hazard sources have been eliminated, substituted or minimised;

- The hazards, and any relevant scenarios or threats leading up to their liberation, have been avoided, isolated, contained or prevented;

- The consequences associated with the hazards have either been mitigated or eliminated;

- Each barrier, or combination thereof, is effective for its hazards, threat lines or scenarios;

- The barriers have independence, redundancy and freedom from common cause failure modes;

- The analysis is sufficiently detailed in terms of generic, clustered or scenario specific threats and barriers, (with details of any relevant procedures, activities, unsafe control actions, natural events, random failures, software errors etc.);

- Appropriate good practice, guidance and standards are complied with;

- All control measures have been applied, unless greatly disproportionate to the risk, based on logic and/or societal expectations; and

- Design error has been avoided (normally by reference to Quality Assurance and management systems).

The entire process and all decisions need to be clearly documented so it can be critically reviewed. High risks managed to ALARP still require monitoring and regular review so it can be determined whether new treatments have become available that may reduce the risk further. Where uncertainty remains as to whether a risk has been managed to ALARP, independent legal advice should be sought for additional guidance. It is a cornerstone of the risk management practice that there is a continuous improvement loop within the process that enables the risk owner to evaluate the effectiveness of their risk management strategy and to adjust the treatments as appropriate with the increased understanding of the applied measures and any new developments that may occur from time to time.

3.2. Legal Reality

From a legal perspective, based on recent precedent and case law, industry and academic approaches to ALARP may be perceived to perpetuate an ongoing problem with the presentation of “ALARP” in two closely related ways, particularly in an Australian legal context. First, industry and academic guidance appears to differentiate between “practicable”, “so far as is reasonably practicable” and “ALARP”. These terms are not different concepts from a legal perspective. They are the same, and the representation of them in the paper is not necessarily accurate from an Australian legislation perspective. Certainly, compliance with the processes described in the previous sections may not be enough to meet an organisation’s legal obligations. We posit that the UK Health and Safety Executive and concepts of tolerability are over relied on and sometimes misplaced in an Australian legal context. It is also worth noting that while regulators might talk about the notion of tolerability, it is not specifically considered in prosecutions for breaches of health and safety legislation. Second, the industry and academic discussion of ALARP primarily conceives the notion as a front end, planning/engineering decision-making process.

In broad terms, reasonably practicable from a legal perspective requires an organisation to develop proper systems to manage hazards in the business and ensure adequate oversight to know that those systems are implemented and effective. However, many engineering-focused conversations about ALARP deal with front end design decision-making and leave it at that, the notion being that provided that the design criteria have been met, the organisation has met its obligations in relation to ALARP. This only represents half of the ALARP equation from a legal context perspective.

Within the various Australian jurisdictions, there is a primary duty of care “owed by a person conducting a business or undertaking to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that the health and safety of other persons is not put at risk from work carried out as part of the conduct of the business or undertaking” [12,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Whilst the term “reasonably practicable” is defined separately in each relevant Act, the definition is reasonably consistent to that provided in the Work Health and Safety (WA) (Section 18 in [12]):

“reasonably practicable, in relation to a duty to ensure health and safety, means that which is, or was at a particular time, reasonably able to be done in relation to ensuring health and safety, taking into account and weighing up all relevant matters including—

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (i)

- (ii)

- (d)

- (e)

The recent New South Wales District Court decision of SafeWork NSW v Saunders Civilbuild Pty Ltd. [39] provides an insight into the complexity and nuance of the term “practicable” from an Australian legal perspective. In the case, a worker had climbed onto the back of a truck to assist unload timber piles and subsequently fell from the truck, suffering a serious head injury that led to his death several days later. The workplace was ultimately found guilty of breaching its duty of care resulting in death. The presiding judge, Scotting J, provided several key definitions, clarifications and relevant considerations in paragraphs 109–130. These, as well as their potential contextualisation to fire services are discussed below.

3.2.1. Guarantee of Safety and the Definition of Risk

From a legal perspective, at paragraph 110 Scotting [39] stated “Safety cannot be ensured if a risk to the health and safety of a worker exists. The existence of the risk constitutes a breach of s 19 of the Act. It is not necessary that there is an accident or that a person is injured: Kirk v Industrial Court of New South Wales (2010) 239 CLR 531”. At paragraph 111 Scotting [38] noted “the word “risk” is not defined in the Act. Risk means the mere possibility of danger and not necessarily actual danger: R v Board of Trustees of the Science Museum [1993] 1 WLR 1171 and Thiess Pty Ltd. v Industrial Court of New South Wales (2010) 78 NSWLR 94”.

Within the context of the current study, firefighting itself is recognised as an inherently dangerous occupation where the risk to the life and safety firefighters is internationally recognised as an occupational hazard [9,40,41,42,43,44]. Therefore, from a legal perspective, it is suggested there is a strong argument that safety cannot be assured and a risk will always be present. Contextualising the considerations of the relevant workplace health and safety legislation [12,34,35,36,37,38] to firefighting operations:

- The likelihood of a worker being exposed to serious harm during firefighting operations is known to be high both within the Australian and the international context [9,40,41,42,43,44].

- As firefighting is the very reason for the existence of fire services, the hazards and risks associated with firefighting and emergency operations, as well as the training, systems, and safe work procedures could be reasonably expected to be intimately understood by fire service executive duty holders, Incident Controllers, and supervising fire service officers,

- Whilst it is irrational to expect fire services to eliminate risks to firefighters by simply not attempting to suppress fires or respond to emergencies, fire services have both suitable and available resources with which to mitigate and minimise risk, including, but not limited to, significant operating budgets, readily available equipment and Personal Protective Clothing, dedicated training programs for firefighters and fire service officers, and access to the lessons learned from hundreds of incident reviews and coronial inquiries [45].

- Whilst analysis of the proportionality of cost to risk for additional safety measures will be considered on a case-by-case basis, it is important to recognise that as was the case in SafeWork NSW v Saunders Civilbuild Pty Ltd. [39], additional safety measures were not identified as being required, but rather it was the non-compliance with existing safe work systems that led to the determination that a breach of duty of care had occurred. Previous research [45] indicates such non-compliances or failures contribute to the majority of firefighting injuries and deaths as opposed to the absence of additional risk mitigation measures.

Importantly, the legal definition of risk, being a mere possibility of danger, is significantly different from the industry definition of “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” [19] and more closely aligns to the industry definition of a hazard, being something that causes or has the potential to cause harm or damage. From a firefighter training perspective, whilst it may be possible to reduce the potential for danger, consideration must be given to the potential realisation of situational irony whereby the act of attempting to reduce potential for danger in training results in increased danger in actual operations, for example, the ladder and harness situation previously described. The potential for situational irony to be realised also extends beyond the training environment whereby the introduction of intended safety systems may actually contribute to a false sense of firefighter safety, especially where those systems may be unsuitable for the extreme conditions faced during emergency operations [43].

3.2.2. Reducing the Risk so Far as Is Reasonably Practicable

From a legal perspective Scotting J ([39], paragraph 113) stated “A duty imposed to ensure health and safety requires the person to eliminate risks to health and safety so far as that is reasonably practicable, and if that cannot be done, to minimise those risks so far as is reasonably practicable: s17 of the Act. The risk should be identified with sufficient precision to determine if it was reasonably practicable to eliminate it or minimise it.” When determining what is practicable, Scotting J ([39], paragraph 115) observed “the state of knowledge applied to the definition of practicable is objective. It is that possessed by persons generally who are engaged in the relevant field of activity, and should not be assessed by reference to the actual knowledge of a specific defendant in particular circumstances: Laing O’Rourke (BMC) Pty Ltd. V Kirwin [2011] WASCA 117 at [33]”. Further, Scotting J ([39], paragraph 116) confirms “the reasonably practicable requirement applies to matters which are within the power of the defendant to control, supervise and manage: Slivak v Lurgi (Aust) Pty Ltd. (2001) 205 CLR 304 at [37] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ).” This statutory duty is not restricted to preventing those risks that are foreseeable, but as Scotting J identifies ([39], paragraph 119), “the duty is to protect against all risks, if that is reasonably practicable. Reasonably practicable means something narrower than physically possible or feasible: Slivak at [53] (Gaudron J)”.

From a firefighting perspective, determining an objective definition of what is reasonably practicable as defined by persons generally engaged in the relevant field is problematic, as attitudes, perceptions and beliefs regarding risk tolerance and acceptable incident decisions have been shown to significantly vary, even amongst Incident Controllers within the same fire service [9]. This problem further increases should a significant safety incident occur during a multi-agency incident where commonality of operational language, process and perception is not guaranteed [17].

It is suggested that this problem extends to the defining the limitations of matters that are within the power of the defendant Incident Controller and fire service to foresee, control, supervise or manage. Based on the findings of multiple formal reviews [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55], accepted industry practice such as Incident Controller checklists and guides [56], fire service standard operating practices, specific legislation and state policy assigning responsibility and broad powers of control to fire services and by delegation to Incident Controllers specifically for the purposes of responding to fires and other emergencies (for example [1,57,58], there may be support for the argument that there is little beyond the fire service and Incident Controller’s broad ability to foresee, control, supervise or manage.

3.2.3. Structured and Systematic Approach to Risk Management

As detailed by Scotting J ([39], paragraph 121) the duty holder has a legal requirement to have “a structured and systematic approach to risk management: WorkCover Authority of NSW v Atco Controls Pty Ltd. (1998) 82 IR 80 at 85 (Hill J) and Inspector Ching v Bros Bins Systems Pty Ltd. [2004] NSWIRComm 197 at 32.” Scotting J continues at ([39], paragraph 123) observing that “a duty holder must have regard not only for the ideal worker but also for one who is careless, inattentive or inadvertent: Dunlop Rubber Australia Ltd. v Buckley (1952) 87 CLR 313 at 320 (Dixon CJ). If there is a foreseeable risk of injury arising from a worker’s negligence in carrying out his or her duties then this is a factor which the duty holder must take into account: Smith v Broken Hill Pty Ltd. (1957) 97 CLR 337 at 343. It may not always be possible to foresee various acts of inadvertence by workers but duty holders must conduct operations on the basis that such acts will occur and they must be guarded against to the fullest extent practicable”.

Previous research [9] reported an absence of robust approaches to risk management within the emergency operations context in Australian fire services. Instead, it was found that both Incident Controllers as individuals as wells as fire service doctrine tended to view risk management as a series of independent controls and decisions as opposed to being part of a singular safety management system. We posit that such approaches are unlikely to be viewed favourably by the court during legal proceedings.

4. Discussion

During large emergencies, such as those experienced during the Black Summer of 2019 in NSW [59], the Yarloop wildfires in Western Australia in 2015 [54], or the Docklands highrise fire in Melbourne in 2014 [60], Incident Controllers are in charge of an Incident Management Team of approximately 50 to 90 personnel responsible for key functional areas including operations, planning and logistics [56], plus hundreds of responding firefighters. The command structure at the incident is designed to maintain a maximum span of control so that no single officer should have more than six direct reports, with the incident response broken into divisions, sectors and crews that need to work in a coordinated effort to achieve the incident objectives and maintain safety in often dangerous and dynamic circumstances. This command structure forms only a single, albeit important, part of the structured and systematic approach to risk management.

Equally as important as an appropriate command structure is the safe work method, which guides the emergency response. In the firefighting context, this takes the form of the shift Incident Action Plan (IAP), which is approved by the Incident Controller and specifically: (1) sets the incident objectives, (2) defines strategies and tactics, in other words the safe work method, (3) identifies the sector, in other words the work location, (4) details the command structure, (5) provides the communication plans, for which emergency safety messages will be relayed, (6) provides key safety messaging, (7) provides incident weather forecast, including potential wind changes, and (8) provides a map showing fire location and other key features. Responding personnel, including novice firefighters, firefighters unfamiliar with the region and terrain, and other agencies including police and ambulance personnel will respond in accordance with their interpretation and understanding of the IAP. For this reason, the IAP must be technically sufficient to guide complex and extensive firefighting efforts, whilst also considering the foreseeable negligence, error or inadvertence of firefighters and supporting staff. Even a single error in the IAP such as an omitted wind change, or incorrect communications channel can have devastating impacts resulting in otherwise avoidable firefighter injury and fatality.

Supporting the IAP are the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), in other words the safe work methods, which personnel are required to comply with in given situations. Whilst the suitability of rigid SOPs during dynamic and complex operations has been the subject of significant scrutiny in policing contexts [61], their suitability in a firefighting context remains a subject for future research. At the other end of the spectrum, application of structureless “dynamic” risk assessments to guide operations and decision-making has also been shown to be problematic [9].

Within the firefighting context, prior to any actual firefighting response is the training and preparation for emergencies. Recognised as one of the key foundations of holistic emergency management in Australia [1,6], preparation involves ensuring both career and volunteer Incident Controllers and firefighters have the skills, knowledge and currency in order to respond effectively and safely to dynamic and dangerous emergencies. Indeed, within SafeWork NSW v Saunders Civilbuild Pty Ltd. [39] the training of the deceased was carefully scrutinised. As previously discussed, using the ladder training scenario analogy, we posit that care must be taken to avoid situational irony whereby training may actually contribute to increased risk of adverse outcomes during emergency incidents.

Whilst the understanding and application of key concepts will inevitably vary depending on the context that they are applied to, or as a result of the lens that they are viewed through [17], the understanding of legal requirements and the application of workplace health and safety concepts within the legal framework is important and has significant potential consequences for the parties involved. At the same time, organisations must be careful not to sacrifice effective safety outcomes in pursuit of purely legal compliance.

For the reasons identified above, Incident Controllers and their respective fire services need to ensure they understand their legal obligations and align their terminology and practices with those legal obligations. We posit that attempting to do so during the escalation phase of an emergency is neither practical given the number of competing incident priorities that require attention in order to avoid the imminent loss of life or damage to significant assets, or conducive to objective and reasoned analysis against complex legal safety standards involving precedent from multiple jurisdictions and industries. Rather, such analysis must be conducted in settings far removed from emergency situations where appropriate stakeholder consultation can be completed and accurate legal advice can be received. Incident Controllers and supervisors (in both frontline and training environments) need to be adequately trained in safe work systems and organisational risk tolerance so that they can apply the correct treatments in order to reduce complex risks as far as reasonably practical. From a training perspective, due care should be taken not to inadvertently introduce future potential harm to operational personnel through inconsistent safe work systems and procedures. Perhaps most critically, fire services need to ensure their understanding and application of the correct standard of care is appropriate. Whilst academic arguments supporting “safe systems of work” may be theoretically sound outside the court room, they may prove to be moot if they do not align to the legal definitions and relevant precedent.

At the same time, it is critically important that industry regulators and legislators contextualise the broadly applicable regulations and legislation to the niche and complete emergency services environment. One suitable approach may include the development and endorsement of industry codes of practice that provide legislative guidance on how legal provisions are to be interpreted in specific contexts [62]. Alternatively, a potentially more complex approach would be for existing safety legislation to be altered to consider the specific circumstances of both career and volunteer emergency services.

Regardless of the approach taken to provide a resolution, until legislators and fire services (and arguably other emergency services including police and ambulance) are of one mind in regard to legislative safety obligations, the potential disruption to effective incident management and emergency response remains an inherent threat.

5. Limitations and Future Research

In addition to the limitations previously discussed in Section 2, other limitations of the study must be acknowledged. This study examines the Australian legislative and fire services dynamic, exploring industry practices within the Australian context. For this reason, it may be perceived that the findings may be limited to Australia and not particularly significant or of interest to fire services and Incident Controllers in other jurisdictions. Importantly, however, the consideration of published research and its subsequent influence on subsequent judicial precedent between Australian, UK, New Zealand and Canadian courts [63] means that it is of particular relevance in those countries. The findings are also relevant to other fire services and jurisdictions, as it provides potentially alternate perspectives on, and approaches to, the problems of providing a safe working environment for firefighters and the legislated duties of care of Incident Controllers that is not unique to Australian firefighters. Even in American legal jurisdictions that have a greater tolerance for firefighter risk and injuries [64,65], the examination of alternate perspectives only serves to enhance the knowledge discipline.

It is also acknowledged that alternate industry methods of hazard calculation and risk justification beyond ALARP and cost benefit analysis may be applied in certain jurisdictions and industries. Whilst this study explored all methods reported within Australian legal and industry contexts, a limitation of this paper is that these alternate methods applied in other jurisdictions are not explored. In order to provide a more holistic analysis of the various industry and legal practices relevant to the subject, expanding the study to an international review is a potential next step for future research. Regardless of the suitability of any measure of consequence, probability and exposure that is applied in industry or academic contexts, the adoption of such measures as legal definitions, measures and thresholds remains critical. In order to address the current discrepancies and limitations identified in this report, future work should not only focus on theoretical research, but the application of that research through its translation into industry codes of practice and legislative amendments.

6. Conclusions

There is a strong argument that models and theories of risk management are important in helping organisations provide a structured basis to tackle risk in their organisations. However, the application and “sign off” of a risk management process is not the same thing as ensuring compliance with legislative work health and safety obligations and in some circumstances can be counterproductive to legal risk management. Indeed, the difference between the legal and academic definitions of risk, the difference in terminology between “ALARP” and “so far as is reasonably practicable”, and the variance between the academic and legal elements for demonstrating the required standard of care has been achieved highlights some of the critical differences between these contexts.

The juxtaposition of academic and industry safety theory against legislation and legal precedent initially presented in this paper highlights the degree of potential uncertainty facing fire services and Incident Controllers when attempting to balance effective emergency response with public and political expectation, industrial agreements, and the legal requirement to maintain a safe workplace for all workers, inclusive of volunteers. In order to provide guidance for fire services and Incident Controllers, in this article, we reviewed the different definitions of the standard of care required through industrial and legal perspectives, examined legal precedent with contextualisation to the fire service context, and explained the importance of applying the correct perspective in light of new workplace health and safety legislation. In doing so, we seek to provide guidance regarding the rules by which fire service personnel must operate, reducing decision-making uncertainty and ultimately improving the standard of emergency response in the most critical of contexts. Acknowledging the subtle differences in legislation between jurisdictions, the degree of similarity means that these findings are equally applicable to all fire services within the Australian context.

Whilst an academic argument may be presented that firefighting is a reasonably unique workplace, which exposes workers to a higher level of harm than many other workplaces, and that certain levels of firefighter injury and even fatality may be theoretically acceptable, no exception or distinction is provided for the firefighting context within the relevant safety legislation. Certainly, the “inherently risky” argument has not carried any weight in industries such as mining and construction for many years, and operations with similar risk profiles to firefighting (e.g., police and military) are not immune to prosecution under work health and safety legislation. Until such time that fire services adopt the legal interpretations and applications and develop true safety management systems as opposed to relying on “dynamic risk assessment” as a defendable position, the ability of fire services and individual Incident Controllers to demonstrate that have managed risk as so far as reasonably practicable will remain ultimately problematic from a legal perspective.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Clinton Kuchel is acknowledged for his assistance and review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. All views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the affiliated institutions. This paper does not replace the need for independent legal advice.

References

- State Emergency Management Committee (SEMC). State Emergency Management Policy—A Strategic Framework for Emergency Management in Western Australia; State Emergency Management Committee: Cockburn, WA, Australia, 2021.

- Catherwood, D.; Edgar, G.K.; Sallis, G.; Medley, A.; Brookes, D. Fire alarm or false alarm?! Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2012, 1, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnin, S.; Brooks, B.; Owen, C. A case study of disaster decision-making in the presence of anomalies and absence of recognition. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2020, 28, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launder, D.; Perry, C. A study identifying factors influencing decision making in dynamic emergencies like urban fire and rescue settings. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2014, 3, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhkanen, H.; Rosemarin, A.; Han, G. How Do We Prioritize When Making Decisions about Development and Disaster Risk? A look at Five Key Trade-Offs; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317344872_How_do_we_prioritize_when_making_decisions_about_development_and_disaster_risk_A_look_at_five_key_trade-offs (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Australian Institute of Disaster Resilience. Incident Management Handbook; Australian Institute of Disaster Resilience: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, J.; Smallman, C. A case study of decision making in emergencies. Risk Manag. 2010, 12, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, P.; Holgate, A.; Clancy, D. Is a contained fire less risky than a going fire? Career and volunteer firefighters. J. Emerg. Manag. 2007, 22, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, G. Exploring ISO31000 Risk Management during Dynamic Fire and Emergency Operations in Western Australia. Fire 2019, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, K. Constructing a Legally Sound Demonstration of ALARP. In Proceedings of the Hazards 29, Birmingham, UK, 22 May 2019; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333667923_Constructing_a_Legally_Sound_Demonstration_of_ALARP (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Safe Work Australia. How to Determine What Is Reasonably Practicable to Meet a Health and Safety Duty; Safe Work Australia: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2013.

- Workplace Health and Safety Act (Western Australia); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2020.

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J. A Framework for Conceptual Contributions in Marketing. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, A.; Power, N.; Alison, L. A systematic review of the potential hurdles of interoperability to the emergency services in major incidents: Recommendations for solutions and alternatives. Cogn. Technol. Work 2013, 16, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, G.; Launder, D.; Cuthbertson, J.; Thompson, M.B. Threat assessment, sense making, and critical decision-making in police, military, ambulance, and fire services. Cogn. Technol. Work 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIA. Principles of OHS Law; Safety Institute of Australia Ltd.: Tullamarine, VIC, Australia, 2012; ISBN 978-0-9808743-1-0. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 31000:2018 Risk Management; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety. What is ‘Reasonably Practicable’? DMIRS: Perth, WA, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.dmp.wa.gov.au/Safety/What-is-reasonably-practicable-4768.aspx (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Health and Safety Executive ALARP at a Glance. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/managing/theory/alarpglance.htm (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Health and Safety Executive-Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) Checklist. Available online: https://www.hse.gov.uk/risk/theory/alarpcheck.htm#footnotes (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety. Petroleum Safety and Major Hazard Facility—Guide; Departmet of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety: Perth, WA, Australia, 2020.

- Robinson, R.; Francis, G. SFAIRP vs. ALARP. In Proceedings of the CORE—Conference on Railway Excellence, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 5 May 2014; Available online: https://www.r2a.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/CORE-2014-paper-SFAIRP-vs-ALARP.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Nesticò, A.; He, S.; De Mare, G.; Benintendi, R.; Maselli, G. The ALARP Principle in the Cost-Benefit Analysis for the Acceptability of Investment Risk. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards v National Coal Board 1 KB 704 at 712 per Asquith LJ; Edwards v National Coal Board, XpertHR: London, UK, 1949.

- Marshall v Gotham Co Ltd. AC 360 at 377 per Lord Keith of Avonholm; XpertHR: London, UK, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- NOPSEMA. ALAR–Guidance Note; National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2015. Available online: https://www.nopsema.gov.au/assets/Guidance-notes/A138249.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- ONRSR. Meaning of Duty to Ensure Safety so Far as is Reasonably Practicable–SFAIRP; Office of the National Rail Safety Regulator: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2016; Available online: https://www.onrsr.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/2412/Guideline-Meaning-of-Duty-to-Ensure-Safety-SFAIRP.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Safe Work Australia. Guide for Major Hazard Facilities. Safety Case: Demonstrating the Adequacy of Safety Management and Control Measures; Safe Work Australia: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2012.

- Government of Australia. Best Practice Regulation Guidance Note Value of Statistical Life; Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2019.

- Work Health and Safety Act (New South Wales); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2011.

- Occupational Health and Safety Act (Victoria); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2004.

- Work Health and Safety Act (South Australia); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2012.

- Work Health and Safety Act (Queensland); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2011.

- Work Health and Safety Act (Tasmania); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2012.

- Work Health and Safety Act (Australian Capital Territory); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2011.

- Work Health and Safety (National Uniform Legislation) Act (Northern Territory); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2011.

- SafeWork NSW v Saunders Civilbuild Pty Ltd. NSWDC 605; Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 2021.

- Mangan, R. Wildland Firefighter Fatalities in the United States: 1990–2006; National Wildfire Coordination Group, Safety and Health Working Team, National Interagency Fire Center: Boise, ID, USA, 2007.

- Blaser, A.R.; Starkopf, L.; Deane, A.M.; Poeze, M.; Starkopf, J. Comparison of Different Definitions of Feeding Intolerance: A Retrospective Observational Study. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.; Buxton-Carr, P. Wildland Fire Suppression Related Fatalities in Canada, 1941–2010: A Preliminary Report. In Proceedings of the 11th International Wildland Fire Safety Summit’, Missoula, MT, USA, 4–8 April 2011; Fox, R.L., Ed.; International Association of Wildland Fire: Missoula, MT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, G.; Habibi, D.; Cattani, M. Improving firefighter tenability during entrapment and burnover: An analysis of vehicle protection systems. Fire Saf. J. 2020, 118, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, G.; Habibi, D.; Cattani, M. Firefighter tenability and its influence on wildfire suppression. Fire Saf. J. 2019, 106, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, G.; Cattani, M.; Ridge, S. Enhancing fire service incident investigation—Translating findings into improved outcomes using PIAM. Saf. Sci. 2021, 145, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keelty, M. A Shared Responsibility. The Report Of The Perth Hills Bushfire February 2011 Review; Government of Western Australia: Perth, WA, Australia, 2011.

- Keelty, M. Appreciating the Risk. Report of the Special Inquiry into the November 2011 Margaret River Bushfire; Government of Western Australia: Perth, WA, Australia, 2012.

- LES. Major Incident Review Black Cat Creek 12 October 2012; Leading Emergency Services: Perth, WA, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, S. Inquest into the Deaths of Kym CURNOW, Thomas BUTCHER, Julia KOHRS-LICHTE and Anna WINTHER (8059/15, 8060/15, 8062/15, 8063/15); Coroner’s Court of Western Australia: Perth, WA, Australia, 2020.

- NIST. Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/publications/finalreport-collapse-world-trade-center-building-7-federal-building-and-fire-safety-0 (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- NIOSH. Death in the Line of Duty: A Summary of a NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation F2003-06; NIOSH: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200306.html (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- NIOSH. Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation Reports; NIOSH: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NIOSH-fire-fighter-face/Default.cshtml?state=ALL&Incident_Year=ALL&Submit=Submit (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Australian Institute of Disaster Resilience. Lessons Management, 2nd ed.; Australian Institute of Disaster Resilience: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, E. Reframing Rural Fire Management. Report of the Special Inquiry into the January 2016 Waroona Fire; Government of Western Australia: Perth, WA, Australia, 2016.

- Government of the United Kingdom. Grenfell Tower Inquiry: Phase 1 Report Overview. Grenfell Tower Inquiry; Government of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-5286-1620-1.

- Australasian Fire and Emergency Services Authorities Council. Decision Making Under Pressure—A Resource for Incident Management Teams; AFAC: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fire Brigades Act (WA); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 1942.

- State Emergency Management Act (WA); Work Health and Safety: Canningtion, WA, Australia, 1942.

- Australian Disaster Resource Knowledge Hub–Bushfires–Black Summer. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/black-summer-bushfires-nsw-2019-20/ (accessed on 4 July 2021).

- Metropolitan Fire Brigade. Post Incident Analysis Report—Lacrosse Docklands 673-675 La Trobe Street, Docklands, 25 November 2014; Metropolitan Fire Brigade: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015.

- Coroner of NSW. Inquest into the Deaths Arising from the Lindt Café Siege—Findings and Recommendations; Coroner of New South Wales: Lidcombe, NSW, Australia, 2017. Available online: http://www.lindtinquest.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/findings-and-recommendations.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety—Codes of Practice. Available online: https://www.commerce.wa.gov.au/worksafe/codes-practice (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Creyke, R.; Hamer, D.; O’Mara, P.; Smith, B.; Taylor, T. Laying Down the Law, 11th ed.; LexisNexis: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2020; ISBN 9780409351934. [Google Scholar]

- MH School of Law. Assumption of the Risk and the Fireman’s Rule. William Mitchell Law Rev. 1981, 7, 1–33. Available online: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol7/iss3/5 (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Madonna v. American Airlines, 82 F.3d 59 2d Cir. NY. 1996. Available online: https://casetext.com/case/madonna-v-american-airlines-inc (accessed on 1 February 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).