Body Composition Changes of United States Smokejumpers during the 2017 Fire Season

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Protocol

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

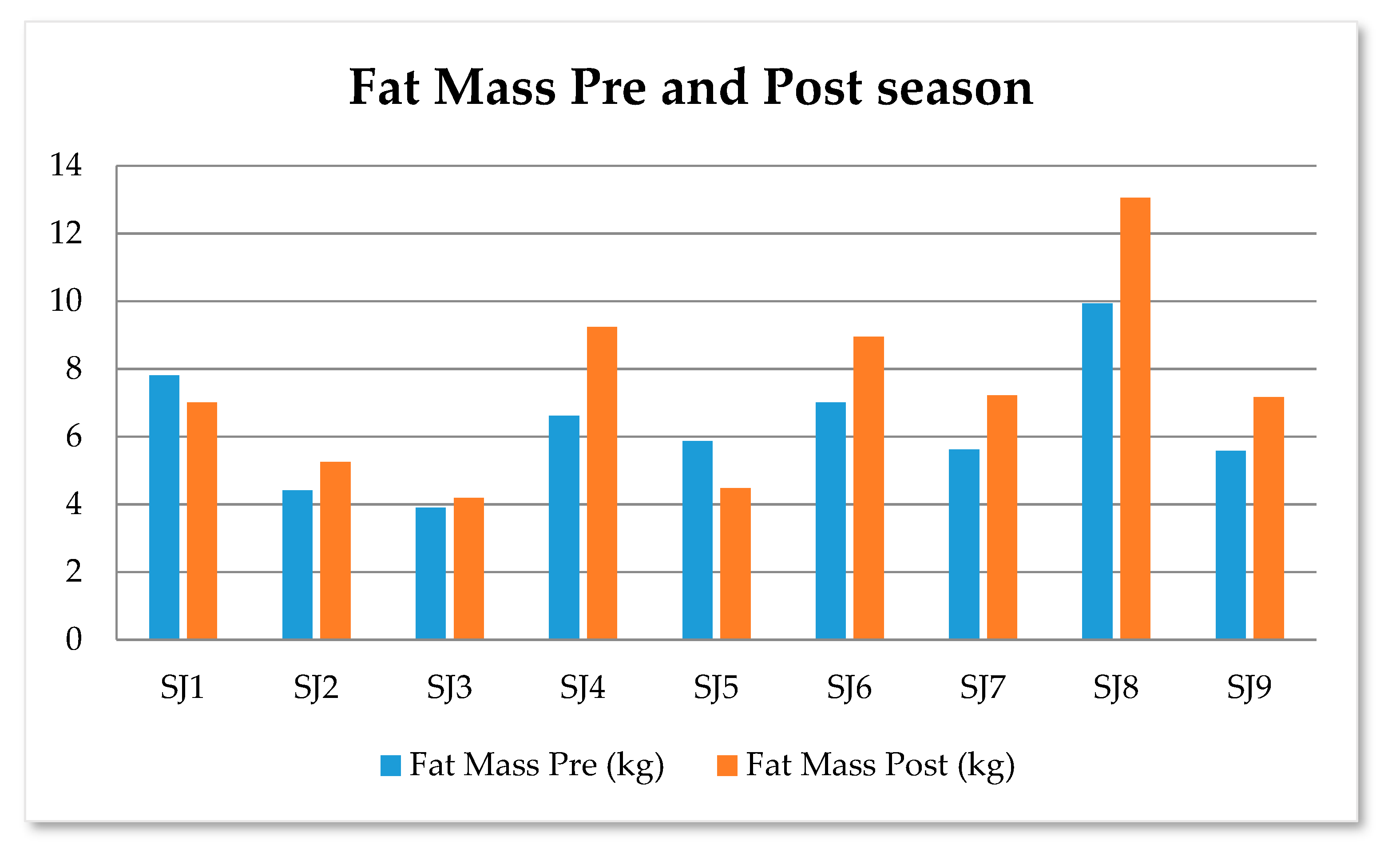

3.1. Body Fat

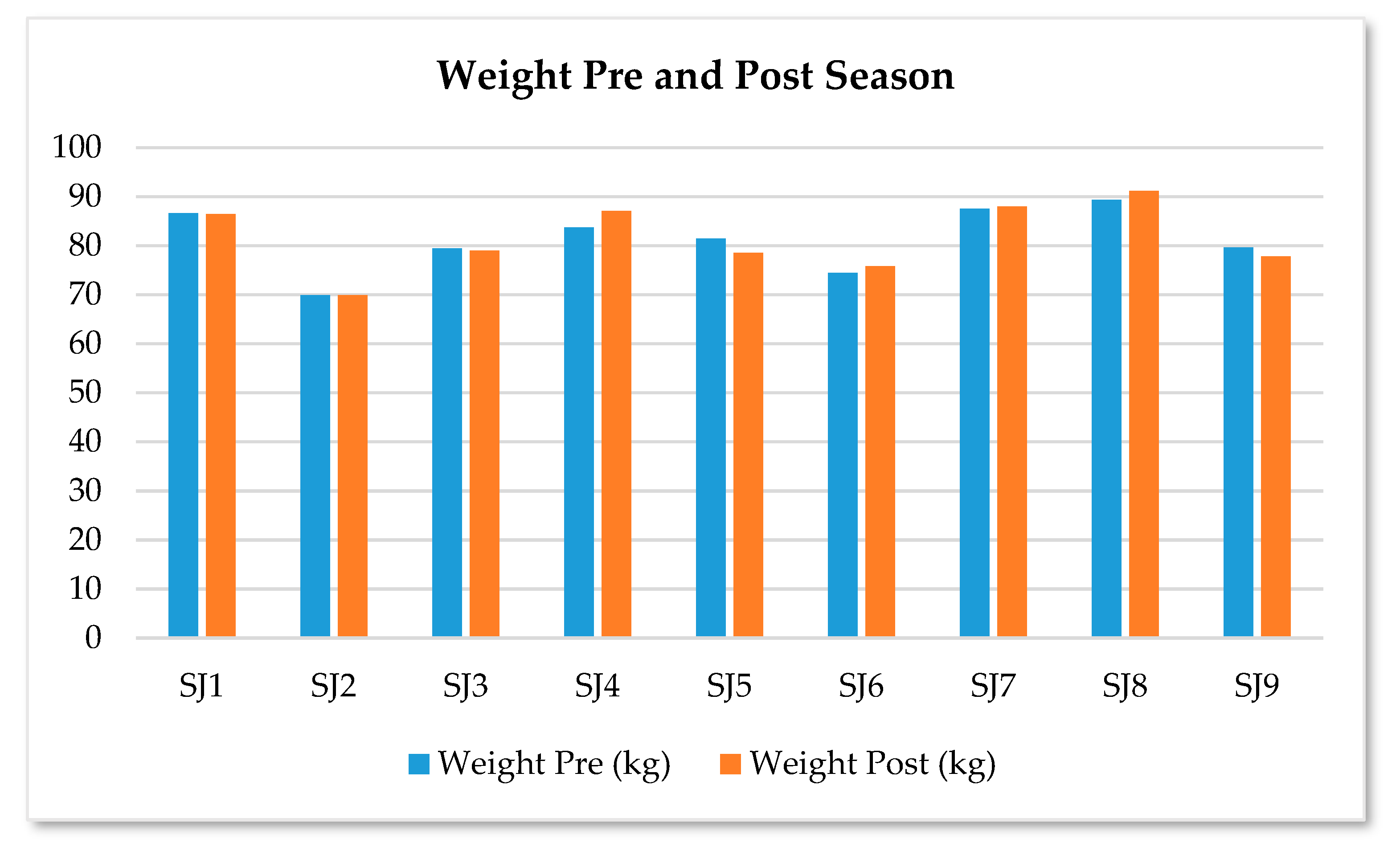

3.2. Body Weight

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heyward, V.; Wagner, D. Applied Body Composition Assessment, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2004; p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, K.R.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Trexler, E.T.; Roelofs, E.J. Body composition and muscle characteristics of division I track and field athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.; Reed, D.B.; Crouse, S.F.; Armstrong, R.B. Pre- and post-season dietary intake, body composition, and performance indices of NCAA division I female soccer players. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2003, 13, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, H.N.; Duey, W.J.; Olson, M.S.; Blessing, D. The relationship between fire fighter physical fitness and performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, H.; Scharff-Olson, M. Fitness and body fat: An issue of performance. Fire Engineering. 1 August 1998. Available online: http://www.fireengineering.com/articles/print/volume-151/issue-8/features/fitness-and-body-fat-an-issue-of-performance.html (accessed on 15 April 2018).

- Gardner, J.W.; Kark, J.A.; Karnei, K.; Sanborn, J.S.; Gastaldo, E.; Burr, P.; Wenger, C.B. Risk factors predicting exertional heat illness in male marine corps recruits. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, S. Body composition of elite American athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 1983, 11, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACSM and the American Dietetic Association, and the Dietitians of Canada. Joint position statement: Nutrition and athletic performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 2130–2145. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, S. Physique, body composition and performance. Aust. Orienteer 2008, 152, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, A.L.; Mermier, C.M.; Wilmerding, M.V.; Bentzur, K.M.; McKinnon, M.M. Body fat estimation in collegiate athletes: an update. Athl. Ther. Today 2009, 14, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana, V.; Kumari, S.; Rao, S.; Balakrishna, N. Effect of changes in body composition profile on VO2max and maximal work performance in athletes. J. Exerc. Physiol. Online 2004, 7, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Scofield, D.; Kardouni, J. The Tactical Athlete: A Product of 21st Century Strength and Conditioning. Strength Cond. J. 2015, 37, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefton, J.; Burkhardt, T. Introduction to the Tactical Athlete Special Issue. J. Athl. Train. 2016, 51, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, D. Estimating energy expenditure in wildland firefighters using a physical activity monitor. Appl. Ergon. 2002, 33, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, B.C.; Shriver, T.C.; Zderic, T.W.; Sharkey, B.J.; Burks, C.; Tysk, S. Total energy expenditure during arduous wildfire suppression. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebine, N.; Rafamantanantsoa, H.H.; Nayuki, Y.; Yamanaka, K.; Tashima, K.; Ono, T.; Saitoh, S.; Jones, P.J. Measurement of total energy expenditure in professional soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, T.; Thomas, V. Estimated daily energy expenditures of professional football players. Ergonomics 1979, 22, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA Forest Service. Work Capacity Test. Work Capacity Testing for Wildland Firefighters; 2002. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/media_wysiwyg/wct_brochure_2002_0.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- USDA Forest Service. Physical Conditioning. In Fire and Aviation Management. National Smokejumper Training Guide; Chapter 4; 2008. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/fire/aviation/av_library/sj_guide/05_physical_conditioning.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- Helms, J. (Ed.) The Dictionary of Forestry; Society of American Foresters: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1998; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Smokejumpers; USDA Forest Service. Available online: https://www.fs.fed.us/fire/people/smokejumpers/ (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- USDA Forest Service. Great Northern Fire Crew. ND. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r1/fire-aviation/?cid=fsp5_030801 (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Klos, P.Z.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Bean, A.; Blades, J.; Clark, M.A.; Dodd, M.; Hall, T.E.; Haruch, A.; Higuera, P.E.; Holbrook, J.D.; et al. Indicators of climate change in Idaho: An assessment framework for coupling biophysical change and social perceptiona. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2015, 7, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, R.; Horswill, C. Body composition in sports: Measurement and applications for weight loss and gain. In Exercise and Sport Science; Garrett, W.E., Jr., Kirkendall, D.T., Eds.; Lippincontt Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, K.; Fleishman, K.; Abt, J.P.; Sell, T.C.; Lovalekar, M.; Nagai, T.; Deluzio, J.; Rowe, R.S.; McGrail, M.A.; Lephart, S.M. Less body fat improves physical and physiological performance in army soldiers. Mil. Med. 2011, 176, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebben, W.P.; Hintz, M.J.; Simenz, C.J. Strength and conditioning practices of major league baseball strength and conditioning coaches. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simenz, C.J.; Dugan, C.A.; Ebben, W.P. Strength and conditioning practices of national basketball association strength and conditioning coaches. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.; Marsh, S.; Domitrovich, J.; Helmcamp, J. Wildland firefighter deaths in the United States: A comparison of existing surveillance systems. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2017, 14, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C. Understanding Factors Contributing to Wildland Firefighter Health, Safety, and Performance: A Pilot Study on Smokejumpers. Master’s Thesis, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, A.; Pollock, M. Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. Br. J. Nutr. 1978, 40, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, W. Body Composition from Fluid Spaces and Density. Analysis of Methods in Techniques for Measuring Body Composition; National Academy of Science; National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 1961; pp. 223–224. [Google Scholar]

- ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 9th ed.; American College of Sports Medicine: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2014; p. 456.

- Beta Technology. Lange Skinfold Caliper. 2008. Available online: http://www.quickmedical.com/downloads/lange-skinfold-caliper-manual.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Garthe, I. Elite athletes in aesthetic and Olympic weight-class sports and the challenge of body weight and body compositions. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29 (Suppl. 1), S101–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sell, K.; Livingston, B. Mid-season physical fitness profile of interagency hotshot firefighters. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2012, 21, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, J.S.; Ham, J.A.; Harger, S.G.; Slivka, D.R.; Ruby, B.C. Effects of an electrolyte additive on hydration and drinking behavior during wildfire suppression. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2008, 19, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudev, S.; Mohan, A.; Mohan, D.; Farooq, S.; Raj, D.; Mohan, V. Validation of body fat measurements by skinfolds and two bioelectrical impedance methods with DEXA—The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study [CURES-3]. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2004, 52, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Konings, C.J.; Kooman, J.P.; Schonck, M.; van Kreel, B.; Heidendal, G.A.; Cheriex, E.C.; van der Sande, F.M.; Leunissen, K.M. Influence of fluid status on techniques used to assess body composition in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit. Dial. Int. 2003, 23, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beam, J.R.; Szymanski, D.J. Validity of 2 skinfold calipers in estimating percent body fat of college-aged men and women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 3448–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dependent Variables | Mean | Std. Deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.1 | 8.28 | 24–49 |

| Height (cm) | 177 | 10.83 | 152.4–190.5 |

| Pre Weight (kg) | 81.32 | 6.39 | 69.85–89.36 |

| Post Weight (kg) | 81.50 | 6.98 | 69.85–91.17 |

| Change Pre- Post weight (kg) | 0.17 * | 6.36 | −3.4–2.9 |

| Pre BF% | 7.63 | 1.89 | 4.83–11.11 |

| Post BF% | 8.94 | 2.90 | 5.25–14.29 |

| Change Pre- Post% | 1.31 ** | 1.64 | −1.5–3.18 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Collins, C.N.; Brooks, R.H.; Sturz, B.D.; Nelson, A.S.; Keefe, R.F. Body Composition Changes of United States Smokejumpers during the 2017 Fire Season. Fire 2018, 1, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1030048

Collins CN, Brooks RH, Sturz BD, Nelson AS, Keefe RF. Body Composition Changes of United States Smokejumpers during the 2017 Fire Season. Fire. 2018; 1(3):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleCollins, Callie N., Randall H. Brooks, Benjamin D. Sturz, Andrew S. Nelson, and Robert F. Keefe. 2018. "Body Composition Changes of United States Smokejumpers during the 2017 Fire Season" Fire 1, no. 3: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1030048

APA StyleCollins, C. N., Brooks, R. H., Sturz, B. D., Nelson, A. S., & Keefe, R. F. (2018). Body Composition Changes of United States Smokejumpers during the 2017 Fire Season. Fire, 1(3), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1030048