Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Extraordinary Wildfire Events

1.2. The Purpose of the Paper

1.3. The Originality and Value of the Paper

2. Terminological Review of Extraordinary Wildfires

2.1. Large, Very Large and Extremely Large Fires

2.2. Megafires

2.3. Extreme Wildfire Events

2.4. Other Terms

2.5. Why Select the Term Extreme Wildfire Event?

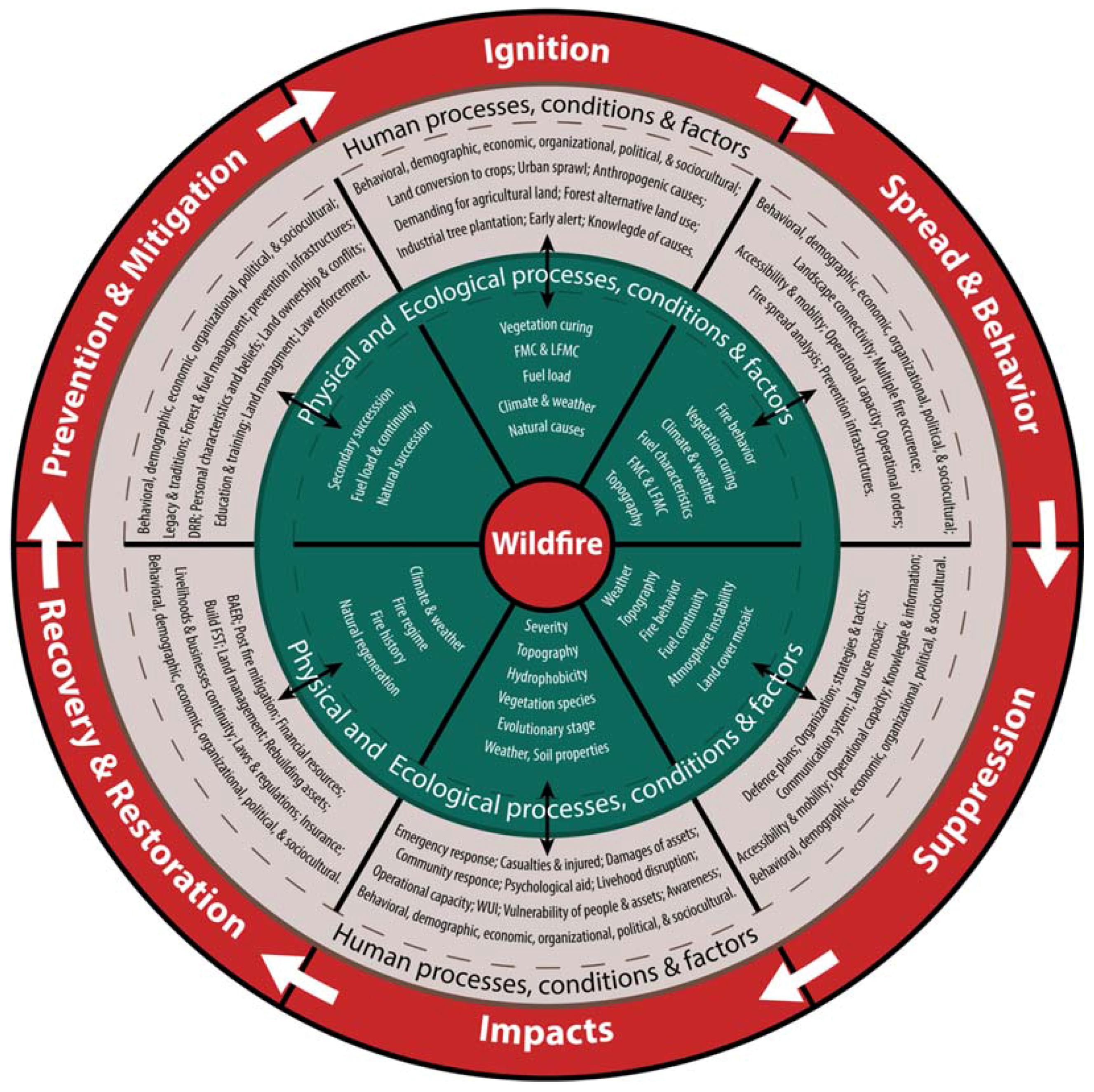

3. Conceptualization of Extreme Wildfire Event

3.1. The Constraints of Fire Size

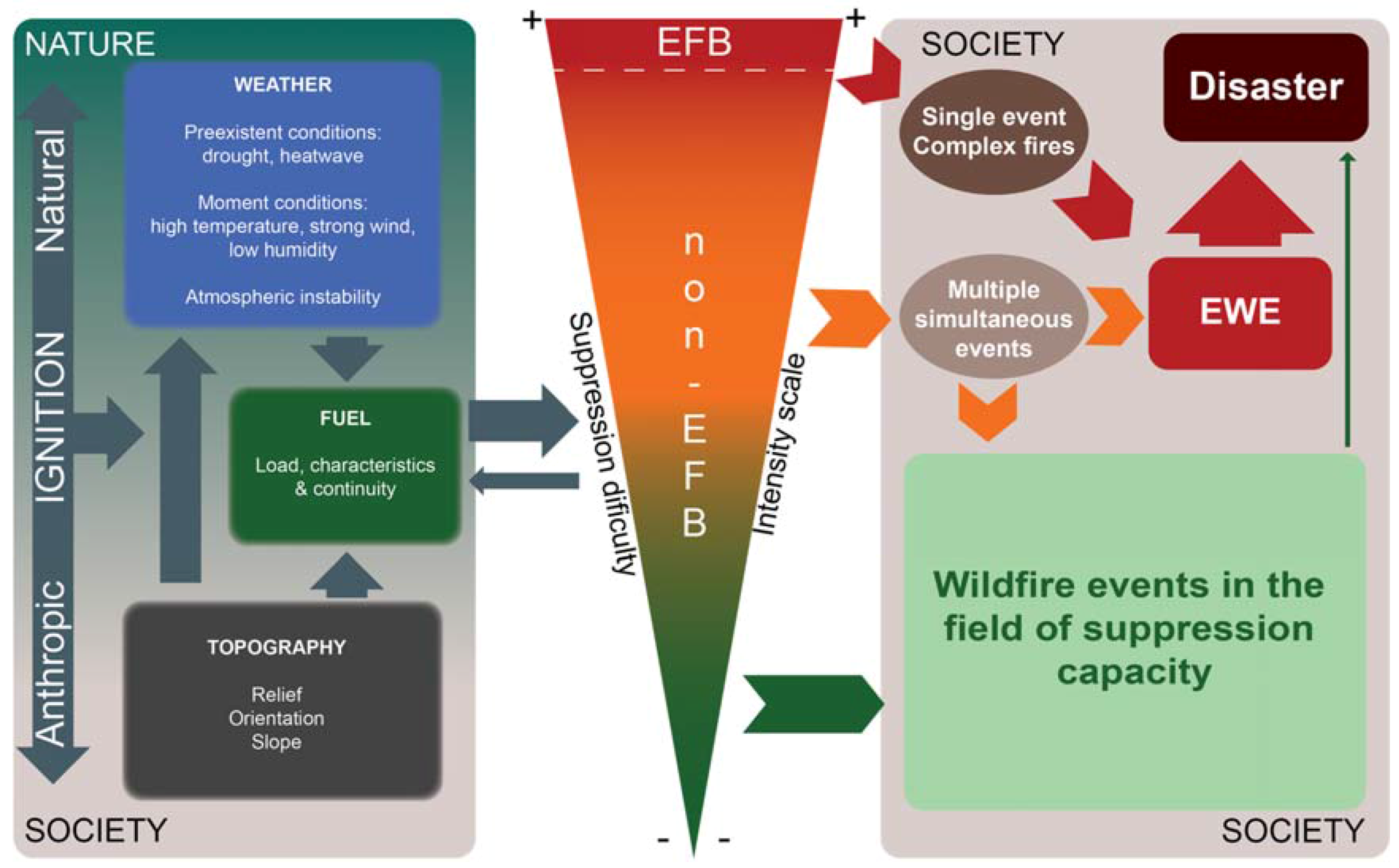

3.2. Extreme Wildfire Event as a Process and an Outcome

3.3. The Definition of Extreme Wildfire Event as a Process and an Outcome

a pyro-convective phenomenon overwhelming capacity of control (fireline intensity currently assumed ≥ 10,000 kWm−1; rate of spread >50 m/min), exhibiting spotting distance > 1 km, and erratic and unpredictable fire behavior and spread. It represents a heightened threat to crews, population, assets, and natural values, and likely causes relevant negative socio-economic and environmental impacts.

4. A Preliminary Proposal of Extreme Wildfire Event Classification

5. Extreme Wildfire Event and Wildfire Disaster

- (i)

- need for temporary relocation (which can be measured in months or years while people await rebuilding efforts and this can create conflict from differences in how recovery is managed) or permanent relocation (this removes factors such as sense of community and place attachment, and can generate conflict if people are moved to other settlements);

- (ii)

- loss of social network connections, so loss of sense of community, and social support;

- (iii)

- loss of heritage, and community symbols, that threatens, or destroys place attachment and identity.

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimensions and Categories | Prevention and Mitigation | Ignition | Spread and Behavior | |

| Human | Processes | Land management Forest and fuel management (e.g., controlled burning, defensible space) Disaster risk reduction (DRR): (i) Vulnerability assessment & reduction; (ii) Risk assessment and communication; localizing knowledge, beliefs and actions; (iii) Enhancing forest resilience; (iv) Enhancing individual, household, and communities’ resilience; and (v) Planning to co-exist with a hazardous environment Public education & awareness Training Preparedness including business continuity planning Law enforcement | Deforestation Afforestation Industrial tree plantation Allocation of forest to alternative land use Urban sprawl Land conversion to crops Increasing demands for agricultural land Land clearing for cattle ranching and conversion to pastures Land abandonment Slash and burn agriculture Slash and burn forest removal Scorched-earth policy (political fires) Burning of fields and houses as measure to expel occupants Land use and natural resources conflictuality | Simulation and analysis of fire spread Operational orders |

| Conditions | Land use Land ownership and conflicts Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) Rural Urban Interface (RUI) Prevention infrastructures Relationship between community and fire management agencies Personal characteristics and beliefs (e.g., fatalism, outcome expectancy) Awareness | Knowledge of causes Early alert | Abandonment of landscape Landscape connectivity Prevention infrastructures Accessibility Mobility conditions Defensible space Multiple contemporary fire occurrence Firefighting crews’ availability Operational capacity | |

| Factors | Behavioral, demographic, economic, organizational, political, and sociocultural. Legacy | Anthropogenic causes (Negligent, intentional, and accidental) Behavioral, demographic, economic, organizational, political, and sociocultural. | Behavioral, demographic, economic, organizational, political, and sociocultural. | |

| Physical and Ecological | Processes | Secondary succession | Vegetation curing, shrinkage and wilting Moisture content of dead and live fuels (FMC & LFMC) | Fire behavior FMC & LFMC Vegetation curing, shrinkage and wilting |

| Conditions | Fuel load and continuity | Dead fine fuel load Climate and Weather (C&W) | Fuel characteristics (Continuity, size packing, density, moisture content, mineral content, vegetation stage) C&W Topography Fire behavior | |

| Factors | Natural succession | Natural causes (Lightning, volcanism, self-combustion, meteorite fall) | C&W Topography | |

| Dimensions and Categories | Suppression | Impacts | Recovery and Restoration | |

| Human | Processes | Defense plans Organization of resources and means (Incident Command System) Strategies and tactics Mopping-up Communication system | Emergency response Casualties and injured people Damages of assets Community response Psychological aid Governance Livelihoods disruption Resilience Reporting damages protocol | Burned area emergency response (BAER): assessment and action Land management Planning to co-exist with a hazardous environment Post fire erosion mitigation Salvage logging Rebuilding assets Livelihoods and businesses continuity Governance |

| Conditions | Land use mosaic Accessibility Mobility level of knowledge and information Operational capacity Communication system | Operational capacity WUI/RUI Vulnerability of people and assets Awareness | Government behavior Laws and regulations Financial resources availability Insurance Build Fire Smart Territory (FST) | |

| Factors | Behavioral, economic, organizational, political, and sociocultural. | Behavioral, demographic, economic, organizational, political, and sociocultural. | Behavioral, demographic, economic, organizational, political, and sociocultural. | |

| Physical and Ecological | Processes | Change of fire behavior | Severity Biomass consumption Soil erosion Surface runoff | Natural regeneration Resilience |

| Conditions | Atmosphere instability Fuel continuity (incl. natural vegetation gaps, e.g., the sea) Vegetal cover mosaic (including that created by past fires) Degree of vegetation curing | Vegetation species Wildfire duration Evolutionary stage of vegetal cover Hydrophobicity | Extent and duration of wildfire season Fire regime Past -fires Fire history | |

| Factors | Weather Topography | C&W Topography Soil properties | C&W Disturbing factors (e.g., animals; short return time of fires) | |

| Fire | Term | Definition or Description | Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danger and weather | Extreme fire danger | Fire danger rating usually includes an Extreme class. In the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) “Extreme” has been redefined after Black Saturday as being between 75 and 100 [148]. In Europe (EFFIS) the Extreme class threshold for Fire Weather Index is 50 (Canadian FWI System). | Informs that conditions are favorable to fast spreading, high-intensity fire of erratic behavior, with the potential to become uncontrollable. Firefighters entrapments and fatalities can result. As a consequence, maximum preparedness (from fire prevention to fire suppression to civil protection) is planned for and implemented. |

| Extreme fire weather Extreme fire weather days Extreme weather conditions | Fire weather conditions corresponding to Extreme fire danger or leading up to Extreme fire behavior, usually defined by the tail end of the fire weather distribution, e.g., FFWI (Fosberg Fire Weather Index) exceeding the 90th percentile [149]; days that have a fire danger rating of 50 or greater for at least one of the three-hourly observations [150]; days with air temperature ≥20ºC at 850hPa [35]. | ||

| Extreme fire days (red flag days) | The onset, or possible onset, of critical weather and dry fuel conditions leading to rapid or dramatic increases in wildfire activity [151,152]. | Extreme fire behavior expected for the next 12 to 72 hours, imposing a red flag warning. | |

| Extreme wildfire burning conditions | Conditions leading to flame and lofted burning ember (firebrand) exposures, home ignition, and unsuccessful firefighting efforts [153]. | Defines conditions of extreme fire behavior in order to declare ban of high risk activities, preventing human-caused wildfires and structure fires, protecting the natural environment and ensuring public safety. | |

| Behavior | Extreme fire behavior | Comprises one or more of the following: high ROS, prolific crowning and/or spotting, presence of fire whirls, deep pyro-convection. Predictability is difficult because such fires often exercise some degree of influence on their environment and behave erratically, sometimes dangerously” [72,74,82,154,155,156].Fire with intensity >4000 kWm−1 [157]. | Defines conditions and fire characteristics that preclude methods of direct, or even indirect, fire control. |

| Extreme fire event Extreme wildfire event Extreme bushfire | Conflagrations associated with violent pyroconvective events. These extreme wildfires can produce pyroCb, thus a fire-caused thunderstorm [2,21]. Extreme bushfire: a fire that exhibits deep or widespread flaming in an atmospheric environment conducive to the development of violent pyroconvection, which manifests as towering pyroCu or pyroCb storms [13,20,82,156].) | Definition of extreme wildfire based on local fire-atmosphere interactions. | |

| Extreme fire-induced winds | Winds generated by low-pressure regions at the flame front. In case of large fires, with the formation of special clouds called pyro-cumulonimbus (pyro CB) [113,158]. | Atmospheric instability descriptors define increased danger in firefighting in relation to continuously changing headfire conditions; unexpected, intense fire behavior on the flanks and back of the fire. | |

| Extreme rates of spread | Value considered extreme: 33 ft /min [159]; 150 ch/h [117] (respectively 10 and 50 m/min. | A component of wildfire hazard based on ROS, FL and suppression effectiveness. Allows evaluating whether a fire can be suppressed and which types (and amount) of resources will be effective. | |

| Extreme fire phenomena | A poorly defined term [160,161]. | NA | |

| Extreme landscape fire | A form of natural disaster [12,68,91,162,163,164]. | NA | |

| Extreme fire (burn) severity | Fire severity is the overall immediate effect of fire resulting from the downwards and upwards components of heat release [165] and can refer to the loss or decomposition of organic matter [166], and in general to the impacts of fire on vegetation and soil. Recently the concept has been enlarged to social impacts [166,167,168,169,170,171]. | Assessment of wildfire impacts. Allows to evaluate the needs of emergency recovery measures and prioritize their distribution within the burned area, as well as to plan other post-fire activities, e.g., salvage logging. | |

| Risk | Extreme wildfire hazard | Hazard assessment based on scoring community design, vegetation, topography, additional rating factors, roofing materials, existing building construction, fire protection, utilities, https://extension.arizona.edu/sites/extension.arizona.edu/files/pubs/az1302.pdf | Used to assist homeowners in assessing the relative wildfire hazard severity around a home, neighborhood, subdivision, or community. The value of extreme is for 84+ points. |

| Extreme wildfire hazard severity | The maximum severity of fire hazard expected to prevail in Fire Hazard Severity Zones based on fuel, slope and fire weather, http//www.fire.ca.gov/fire_prevention/fire_prevention_wildland_faqs | Identification of maximum severity of fire hazard to define the mitigation strategies to reduce risk. | |

| Extreme wildfire threat | The Wildfire Behavior Threat Class estimates potential wildfire behavior. An Extreme (Red) class consists of forested land with continuous surface fuels that will support intermittent or continuous crown fires [172]. | Integrates many different aspects of fire hazard and risk and provides spatially-explicit tools for understanding the variables that contribute to wildfire threat. | |

| Regime | Extreme fire regime | The time series of the largest fire (i.e., area burned) per year [173]. | Term used for statistical purposes. |

| Extreme fire seasons | The period of time when fires typically occur or when they are likely to be of high intensity or burn large expanses [174]. | Supports fire prevention and preparedness based on fire-promoting conditions (drought, solar radiation, relative humidity, air temperature) that have extreme values, e.g., the 90th percentile. |

References

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Williamson, G.J.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Kolden, C.A.; Cochrane, M.A.; Smith, A.M.S. Human exposure and sensitivity to globally extreme wildfire events. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcrae, R.; Sharples, J. Assessing mitigation of the risk from extreme wildfires using MODIS hotspot data. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Gold Coast, Australia, 29 November–4 December 2015; pp. 250–256. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, D.; Bednar, L.; Mees, R. Do one percent of forest fires cause ninety-nine percent of the damage? For. Sci. 1989, 35, 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.T.; Hyde, A.C. The mega-fire phenomenon: Observations from a coarse-scale assessment with implications for foresters, land managers, and policymakers. In Proceedings of the Society of American Foresters 89th National Convention, Orlando, FL, USA, 30 September–4 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Albright, D.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Ritsov, A.; Moore, P.F.; De Morais, J.C.M.; Leonard, M.; Miguel-Ayanz, J.S.; Xanthopoulos, G.; van Lierop, P. Findings and Implications from a Coarse-Scale Global Assessment of Recent Selected Mega-Fires. In Proceedings of the 5th International Wildland Fire Conference, Sun City, South Africa, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, D.X.; Figueiredo Almeida, M.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Raposo, J.; Viegas, M.T.; Oliveira, R.; Alves, D.; Pinto, C.; Jorge, H.; Rodrigues, A.; et al. O Complexo de Incêndios de Pedrogão Grande E Concelhos Limítrofes, Iniciado a 17 de Junho de 2017; Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2017.

- Comissão Técnica Independente. Análise E Apuramento de Factos Relativos Aos Incêndios Que Ocorreram Em Pedrogão Grande, Castanheira de Pera, Ansião, Alvaiázere, Figueiró Dos Vinhos, Arganil, Góis, Penela, Pampilhosa Da Serra, Oleiros E Sertã, Entre 17 E 24 de Junho de 2017; Assembleia da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, D.X. Are extreme forest fires the new normal? The Conversation, 9 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, L.; Gray, R.W.; Burton, P.J. Megafires in BC—Urgent Need to Adapt and Improve Resilience to Wildfire; Faculty of Forestry: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Attiwill, P.M.; Adams, M.A. Mega-fires, inquiries and politics in the eucalypt forests of Victoria, south-eastern Australia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.C.; Opperman, T.S. LANDFIRE—A national vegetation/fuels data base for use in fuels treatment, restoration, and suppression planning. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 294, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, S.H.; Santín, C. Global trends in wildfire and its impacts: Perceptions versus realities in a changing world. Philos Trans. R. Soc. B. Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharples, J.J.; Cary, G.J.; Fox-Hughes, P.; Mooney, S.; Evans, J.P.; Fletcher, M.-S.; Fromm, M.; Grierson, P.F.; McRae, R.; Baker, P. Natural hazards in Australia: Extreme bushfire. Clim. Chang. 2016, 139, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescaroli, G.; Alexander, D. A definition of cascading disasters and cascading effects: Going beyond the “toppling dominos” metaphor. Planet@Risk 2015, 2, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fifer, N.; Orr, S.K. The Influence of Problem Definitions on Environmental Policy Change: A Comparative Study of the Yellowstone Wildfires. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 636–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morss, R.E. Problem Definition in Atmospheric Science Public Policy: The Example of Observing-System Design for Weather Prediction. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 86, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, S.J. Problems, paradoxes, paradigms: Triangulating fire research. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2007, 16, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail-Zadeh, A.T.; Cutter, S.L.; Takeuchi, K.; Paton, D. Forging a paradigm shift in disaster science. Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 969–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Alcubierre, P.; Castellnou Ribau, M.; Larrañaga Otoxa de Egileor, A.; Miralles Bover, M.; Daniel Kraus, P. Prevention of Large Wildfires Using the Fire Types Concept; Direccio General de Prevencio, Extincio D’incendis I Salvaments, Departament D’interior; Generalitat de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, R. Extreme Fire: A Handbook; ACT Government and Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre: East Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2010.

- McRae, R.; Sharples, J. A conceptual framework for assessing the risk posed by extreme bushfires. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2011, 26, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Barbero, R.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Steel, E.A.; K Larkin, N. Modeling very large-fire occurrences over the continental United States from weather and climate forcing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 124009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, N.K.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Barbero, R.; Kolden, C.; McKenzie, D.; Potter, B.; Stavros, E.N.; Steel, E.A.; Stocks, B.J. Future Megafires and Smoke Impacts—Final Report to the Joint Fire Science Program Project; FSP Project No. 11-1-7-4; Joint Fire Science Program Project: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015.

- Fernandes, P.M.; Monteiro-Henriques, T.; Guiomar, N.; Loureiro, C.; Barros, A.M.G.G. Bottom-Up Variables Govern Large-Fire Size in Portugal. Ecosystems 2016, 19, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, J.A.; Key, C.H.; Kolden, C.A.; Kane, J.T.; van Wagtendonk, J.W. Fire Frequency, Area Burned, and Severity: A Quantitative Approach to Defining a Normal Fire Year. Fire Ecol. 2011, 7, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F.; Senra, F.V. Grandes Incendios Forestales. Causas Y Efectos de Una Ineficaz Gestión Del Territorio; WWF/Adena: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A.M.; Allan, G. Large fires, fire effects and the fire-regime concept. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2008, 17, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, D.X. Extreme Fire Behaviour. In Forest Management: Technology, Practices and Impact; Bonilla Cruz, A.C., Guzman Correa, R.E., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, A.J.; Boer, M.M.; McCaw, W.L.; Grierson, P.F. Scale-dependent thresholds in the dominant controls of wildfire size in semi-arid southwest Australia. Ecosphere 2014, 5, art93–art93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICNF. Análise Das Causas Dos Incêndios Florestais—2003–2013; ICNF: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.G.; Caramelo, L.; Orozco, C.V.; Costa, R.; Tonini, M. Space-time clustering analysis performance of an aggregated dataset: The case of wildfires in Portugal. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 72, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Pereira, M.G.; Tonini, M. Space-time clustering analysis of wildfires: The influence of dataset characteristics, fire prevention policy decisions, weather and climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonini, M.; Pereira, M.G.; Parente, J.; Vega Orozco, C. Evolution of forest fires in Portugal: From spatio-temporal point events to smoothed density maps. Nat. Hazards 2017, 85, 1489–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, L.D.; Barbati, A.; Corona, P. Geospatial analysis of woodland fire occurrence & recurrence in Italy. Ann. Silv. Res. 2017, 41, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardil, A.; Molina, D.M.; Ramirez, J.; Vega-García, C. Trends in adverse weather patterns and large wildland fires in Aragón (NE Spain) from 1978 to 2010. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardil, A.; Salis, M.; Spano, D.; Delogu, G.; Molina Terrén, D. Large wildland fires and extreme temperatures in Sardinia (Italy). iForest Biogeosci. For. 2014, 7, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubo María, J.E.; Enríquez Alcalde, E.; Gallar Pérez-Pastor, J.J.; Jemes Díaz, V.; López García, M.; Mateo Díez, M.L.; Muñoz Correal, A.; Parra Orgaz, P.J. Los Incendios Forestales En España; Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulos, A.P.; Vlahou, M.; Anagnostopoulou, C.G.; Mitsopoulos, I.D. Impact of drought on wildland fires in Greece: Implications of climatic change? Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, B.G.; Prather, J.W.; Xu, Y.; Hampton, H.M.; Aumack, E.N.; Sisk, T.D. Mapping the probability of large fire occurrence in northern Arizona, USA. Landsc. Ecol. 2006, 21, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradstock, R.A.; Cohn, J.S.; Gill, A.M.; Bedward, M.; Lucas, C. Prediction of the probability of large fires in the Sydney region of south-eastern Australia using fire weather. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2009, 18, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverly, J.L.; Martell, D.L. Characterizing extreme fire and weather events in the Boreal Shield ecozone of Ontario. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2005, 133, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, C.S.; Shindler, B.A. Trust, acceptance, and citizen–agency interactions after large fires: Influences on planning processes. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2010, 19, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, C.P.; Edwards, A.C.; Russell-Smith, J. Big fires and their ecological impacts in Australian savannas: Size and frequency matters. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2008, 17, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsopoulos, I.; Mallinis, G. A data-driven approach to assess large fire size generation in Greece. Nat. Hazards 2017, 88, 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, R.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Larkin, N.K.; Kolden, C.A.; Stocks, B. Climate change presents increased potential for very large fires in the contiguous United States. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2015, 24, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, R.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Brown, T.J. Seasonal reversal of the influence of El Niño-Southern Oscillation on very large wildfire occurrence in the interior northwestern United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 3538–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyn, A.; White, P.S.; Buhk, C.; Jentsch, A. Environmental drivers of large, infrequent wildfires: The emerging conceptual model. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2007, 31, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoldt, D.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Keane, R.E.; Lenihan, J.M.; McKenzie, D.; Weise, D.R.; Sandberg, D.V. Assessing the Effects of Fire Disturbance on Ecosystems: A Scientific Agenda for Research and Management; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 1999.

- Castellnou, M.; Miralles, M. The changing face of wildfires. Cris Response. 2009, 5, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, T.; Leonard, M.G.M. The megafire phenomenon: Some Australian perspectives. In The 2007 Institute of Foresters of Australia and New Zealand Institute of Forestry Conference; Institute of Foresters of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. The 1910 Fires a Century Later: Could They Happen Again? In Proceedings of the Inland Empire Society of American Foresters Annual Meeting, Wallace, ID, USA, 20–22 May 2010; pp. 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- The Brooking Institution. The Mega-Fire Phenomenon. Towards a More Effective Management Model; The Brooking Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heyck-Williams, S.; Anderson, L.; Stein, B.A. Megafires: The Growing Risk to America’s Forests, Communities, and Wildlife; National, W., Ed.; National Wildlife Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.N.; Atkinson, R.D.; Lewis, J.W. Mapping Wildfire Hazards and Risks; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, A. Mega fire emissions in Siberia: Potential supply of bioavailable iron from forests to the ocean. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 1679–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannom, K.O.; Tinkham, W.T.; Smith, A.M.S.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Newingham, B.A.; Hall, T.E.; Morgan, P.; Strand, E.K.; Paveglio, T.B.; Anderson, J.W.; et al. Defining extreme wildland fires using geospatial and ancillary metrics. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2014, 23, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedim, F.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Leone, V. Forest Fires in Europe: Facts and Challenges. In Wildfire Hazards, Risks and Disasters; Paton, D., Buergelt, P.T., McCaffrey, S., Tedim, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, T. What Megablazes Tell Us About the Fiery Future of Climate Change. Rolling Stone, 15 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Binkley, D. Exploring the Mega-Fire Reality 2011: The Forest Ecology and Management Conference. Fire Manag. Today 2012, 72, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J.M.C.; Sousa, A.M.O.; Sá, A.C.L.; Martín, M.P.; Chuvieco, E. Regional-scale burnt area mapping in Southern Europe using NOAA-AVHRR 1 km data. In Remote Sensing of Large Wildfires; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.A. Mega-fires, tipping points and ecosystem services: Managing forests and woodlands in an uncertain future. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Goodrick, S.; Stanturf, J.T.H.; Liu, Y. Impacts of Mega-Fire on Large U.S. Urban Area Air Quality under Changing Climate; JFSP Project 11-1-7-2; Forest Service, SRS-Ctr for Forest Disturbance Science: Athens, GA, USA, 2013.

- Xanthopoulos, G.; Athanasiou, M.; Zirogiannis, N. Use of fire for wildfire suppression during the fires of 2007 in Greece. In Proceedings of the II International Conference on Fire Behaviour and Risk, Alghero, Sardinia, Italy, 26–29 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- French, B.J.; Prior, L.D.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.J.S. Cause and effects of a megafire in sedge-heathland in the Tasmanian temperate wilderness. Aust. J. Bot. 2016, 64, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Exploring the onset of high-impact mega-fires through a forest land management prism. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Albright, D. Findings and implications from a coarse-scale global assessement of recent selected mega-fires. In Proceedings of the 5th International Wildland Fire Conferenceth International Wildland Fire Conference, Sun City, South Africa, 9–13 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Lin, Y.-L.; Kaplan, M.L.; Charney, J.J. Synoptic-Scale and Mesoscale Environments Conducive to Forest Fires during the October 2003 Extreme Fire Event in Southern California. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2009, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.O.; Dold, J.W. Linking landscape fires and local meteorology—A short review. JSME Int J Ser B. 2006, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oliveri, S.; Gerosa, G.; Pregnolato, M. Report on Extreme Fire Occurrences at Alpine Scale. MANFRED Project—Regional Report on Extreme Fire Occurrences. 2012. Available online: http://www.manfredproject.eu/ (accessed on 14 January 2018).

- Jain, T.B.; Pilliod, D.S.; Graham, R.T. Tongue-Tied: Confused meanings for common fire terminology can lead to fuels mismanagement. A new framework is needed to clarify and communicate the concepts. Wildfire Mag. 2004, July/August. 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, H.F.; Swetnam, T.W. The Wildfires of 1910: Climatology of an Extreme Early Twentieth-Century Event and Comparison with More Recent Extremes. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2013, 94, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, G.M. Atmospheric Conditions Related to Blowup Fires. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Asheville, FL, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, D.X.; Simeoni, A. Eruptive Behaviour of Forest Fires. Fire Technol. 2011, 47, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.; Cohen, J. Firefighter Safety Zones: A Theoretical Model Based on Radiative Heating. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 1998, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelon, F.-J.; Sauvagnargues, S.; Dusserre, G.; Balbi, J.-H. Generalized blaze flash, a “Flashover” behavior for forest fires—Analysis from the firefighter’s point of view. Open J. For. 2014, 4, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Viegas, D.X. A mathematical model for forest fires blowup. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2004, 177, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, D.X. Parametric study of an eruptive fire behaviour model. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2006, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, C.C. A Study of Mass Fires and Conflagrations; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Redding, CA, USA, 1963.

- Schmalz, R.F. Conflagrations: Disastrous urban fires. In Natural and Tecnological Disasters: Causes, Effects and Preventive Measures; Majumdar, S.K., Forbes, G.S., Miller, E.W., Schmalz, R.F., Eds.; The Pennsylvania Academy of Science: University Park, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, D.F.; Alexander, M.E. (Eds.) Glossary of Forest Fire Management Terms, 4th ed.; Canadian Committee on Forest Fire Management, National Research Council of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Countryman, C.M. Mass Fires and Fire Behavior; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Asheville, FL, USA, 1964.

- Werth, P.A.; Potter, B.E.; Clements, C.B.; Finney, M.A.; Goodrick, S.L.; Alexander, M.E.; Cruz, M.G.; Forthofer, J.A.; McAllister, S.S. Synthesis of Knowledge of Extreme Fire Behavior: Volume 1 for Fire Management. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Butry, D.T.; Mercer, D.E.; Prestemon, J.P.; Pye, J.M.; Holmes, T.P. What is the Price of Catastrophic Wildfire? J. For. 2001, 99, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.G.; Sullivan, A.L.; Gould, J.S.; Sims, N.C.; Bannister, A.J.; Hollis, J.J.; Hurley, R.J. Anatomy of a catastrophic wildfire: The Black Saturday Kilmore East fire in Victoria, Australia. For. Ecol. Manage. 2012, 284, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvidenko, A.Z.; Shchepashchenko, D.G.; Vaganov, E.A.; Sukhinin, A.I.; Maksyutov, S.S.; McCallum, I.; Lakyda, I.P. Impact of wildfire in Russia between 1998–2010 on ecosystems and the global carbon budget. Dokl Earth Sci. 2011, 441, 1678–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, G. Forest fire policy scenarios as a key element affecting the occurrence and characteristics of fire disasters. In Proceedings of the IV International Wildland Fire Conference, Sevilla, Spain, 13–17 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pausas, J.G.; Llovet, J.; Rodrigo, A.; Vallejo, R. Are wildfires a disaster in the Mediterranean basin? — A review. Int. J. Wildl. Fire. 2008, 17, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Wahren, C.H.; Tolsma, A.D.; Sanecki, G.M.; Papst, W.A.; Myers, B.A.; McDougall, K.L.; Heinze, D.A.; Green, K. Large fires in Australian alpine landscapes: their part in the historical fire regime and their impacts on alpine biodiversity. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2008, 17, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Hall, T.; Smith, A.M.S.S. Understanding social impact from wildfires: Advancing means for assessment. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2015, 24, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifsnyder, W.E. Weather and Fire Control Practices-197. In Proceedings of the 10th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, Fredericton, NB, Canada, 20–21 August 1970; pp. 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, M.; Cary, G. Socially disastrous landscape fires in south-eastern Australia: impacts, responses, implications. In Wildfire and Community: Facilitating Preparedness and Resilience; Paton, D., Tedim, F., Eds.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2012; pp. 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.J.; Bradstock, R.A. Large fires and their ecological consequences: Introduction to the special issue. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2008, 17, 685–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L. The Changing Context of Hazard Extremes: Events, Impacts, and Consequences. J. Extreme Events 2016, 3, 1671005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, G.M. Forest fire behavior. In Forest Fire: Control and Use; Brown, A.A., Davis, K.P., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959; pp. 90–123. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.E.; Cruz, M.G. Interdependencies between flame length and fireline intensity in predicting crown fire initiation and crown scorch height. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2012, 21, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.M.; Wooster, M.J.; Paugam, R.; Wang, X.; Lynham, T.J.; Johnston, L.M. Direct estimation of Byram’s fire intensity from infrared remote sensing imagery. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2017, 26, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremens, R.L.; Dickinson, M.B.; Bova, A.S. Radiant flux density, energy density and fuel consumption in mixed-oak forest surface fires. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2012, 21, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Roy, D.P.; Boschetti, L.; Kremens, R. Exploiting the power law distribution properties of satellite fire radiative power retrievals: A method to estimate fire radiative energy and biomass burned from sparse satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, D19303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, N.P. Quantifying bushfires. Math. Comput. Model. 1990, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.E. Calculating and interpreting forest fire intensities. Can. J. Bot. 1982, 60, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, E.; McKee, D.; Thomas, D. Health consequences of forest fires in Indonesia. Demography 2005, 42, 29–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Pereira, G.; Uhl, S.A.; Bravo, M.A.; Bell, M.L. A systematic review of the physical health impacts from non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke. Environ. Res. 2015, 136, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, C.; Tesfaigzi, Y.; Bassein, J.A.; Miller, L.A. Wildfire smoke exposure and human health: Significant gaps in research for a growing public health issue. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 55, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolhurst, K.G.; Chatto, K. Development, behaviour and threat of a plume-driven bushfire in west-central Victoria. In Development, Behaviour, Threat and Meteorological Aspects of a Plume-Driven Bushfire in West-Central Victoria, Berringa Fire February 25-26, 1995; Chatto, K., Ed.; Fire Management, Dept. of Natural Resources & Environment East Melbourne: East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 1999; pp. 1.1–1.21. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S.; Anderson, W.; Kilinc, M.; Fogarty, L. The relationship between fire behaviour measures and community loss: An exploratory analysis for developing a bushfire severity scale. Nat. Hazards 2012, 63, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Off the Richter: Magnitude and Intensity Scales for Wildland Fire. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Fire Ecology and Management Congress: Changing Fire Regimes: Context and Consequences, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–17 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, R. Lessons from Recent Research into Fire in the High Country: Checklist for Fire Observers; Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC: East Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Hillen, T. The Spotting Distribution of Wildfires. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charney, B.E.; Potter, J.J. Convection and downbursts. Fire Manag. Today 2017, 75, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, N.P.; Clements, C.B. Cold Smoke: Smoke-induced density currents cause unexpected smoke transport near large wildfires. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 11513–11520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareau, N.P.; Clements, C.B. Environmental controls on pyrocumulus and pyrocumulonimbus initiation and development. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 4005–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.; Reeder, M.J. Severe convective storms initiated by intense wildfires: Numerical simulations of pyro-convection and pyro-tornadogenesis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tory, W.; Thurston, K.J. Pyrocumulonimbus: A Literature Review; Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC: East Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.E.; Cruz, G.M. The elliptical shape and size of wind-driven crown fires. Fire Manag. Today 2014, 73, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.; Gould, J.S.; Alexander, M.E.; Sullivan, A.L.; McCaw, W.L.; Matthews, S. A Guide to Rate of Fire Spread Models for Australian Vegetation; Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council Ltd. and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Viegas, D.X.; Raposo, J.R.; Davim, D.A.; Rossa, C.G. Study of the jump fire produced by the interaction of two oblique fire fronts. Part 1. Analytical model and validation with no-slope laboratory experiments. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2012, 21, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.H.; Burgan, R.E. Standard Fire Behavior Fuel Models: A Comprehensive Set for Use with Rothermel’s Surface Fire Spread Model; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst, K.G.; Chong, D.M. Incorporating the Effect of Spotting into Fire Behaviour Spread Prediction Using PHOENIX-Rapidfire; Bushfire CRC Ltd.: East Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Albini, F.A. Potential Spotting Distances from Wind-Driven Surface Fires; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1983.

- Pinto, C.; Viegas, D.; Almeida, M.; Raposo, J. Fire whirls in forest fires: An experimental analysis. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 87, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forthofer, J.M.; Goodrick, S.L. Review of Vortices in Wildland Fire. J. Combust. 2011, 2011, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Botelho, H.S. A review of prescribed burning effectiveness in fire hazard reduction. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2003, 12, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, K.; Martell, D. A review of initial attack fire crew productivity and effectiveness. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 1996, 6, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.E.; De Groot, W.J. Fire Behavior in Jack Pine Stands as Related to the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index (FWI) System; Canadian Forestry Service, Northwest Region: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.E.; Lanoville, R.A. Predicting Fire Behavior in the Black Spruce-Lichen Woodland Fuel Type of Western and Northern Canada. Forestry Canada, Northern Forestry Center: Edmonton, AB, Canada.

- Alexander, M.E.; Cole, F.V. Predicting and interpreting fire intensities in Alaskan black spruce forests using the Canadian system of fire danger rating. Managing Forests to Meet People’s Needs. In Proceedings of the 1994 Society of American Foresters/Canadian Institute of Forestry Convention, Bethesda, MD, USA, 18–22 September 1994; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wotton, B.M.; Flannigan, M.D.; Marshall, G.A. Potential climate change impacts on fire intensity and key wildfire suppression thresholds in Canada. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 95003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC. Bushfire Research Response Interim Report; Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC: East Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chevrou, R. Incendies de Forêts Catastrophes; Conseil General du Genie Rural, des Eaux et des Forêts: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.E.; Thorburn, W.R. LACES: Adding an “A” for Anchor point(s) to the LCES wildland firefighter safety system. In Current International Perspectives on Wildland Fires, Mankind and the Environment; Butler, B.W., Mangan, R.J., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, R. European Glossary for Wildfires and Forest Fires, European Union-INTERREG IVC, 2012.

- Teie, WC. Firefighter’s Handbook on Wildland Firefighting: Strategy, Tactics and Safety; Deer Valley Press: Rescue, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barboni, T.; Morandini, F.; Rossi, L.; Molinier, T.; Santoni, P.-A. Relationship Between Flame Length and Fireline Intensity Obtained by Calorimetry at Laboratory Scale. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2012, 184, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedim, F. O contributo da vulnerabilidade na redução do risco de incêndio florestal. In Riscos Naturais, Antrópicos e Mistos. Homenagem ao Professor Doutor Fernando Rebelo; Lourenço, L., Mateus, M.A., Eds.; Departamento de Geografia, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner, B.; Gaillard, J.C.; Kelman, I. Handbook of Hazards and Disaster Risk Reduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek, P.M. Human Domination of Earth’s Ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.; Keeley, J. Fire as a global “herbivore”: The ecology and evolution of flammable ecosystems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlan, M.R.; Petty, A.M. Linking humans and fire: A proposal for a transdisciplinary fire ecology. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2012, 21, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Disaster Relief Organization (UNISDR). Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mayner, L.; Arbon, P. Defining disaster: The need for harmonisation of terminology. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma Stud. 2015, 19, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, A.; Norris, F. Definitions and concepts in disaster research. In Methods for Disaster Mental Health Research; Norris, F., Galea, S., Friedman, M., Watson, P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Routes to posttraumatic growth through cognitive processing. In Promoting Capabilities to Manage Posttraumatic Stress: Perspectives on Resilience; Paton, D., Violanti, J.M., Smith, L.M., Eds.; Charles C. Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2003; pp. 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L. Social Aspects of Disasters and Their Relevance to Pre-Disaster Planning; University of Delaware, Disaster Research Center: Newark, DE, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L.; Dynes, R.R. Response to Social Crisis and Disaster. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1977, 3, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Jonhston, D.; Mamula-Seadon, L.; Kenney, C.M. Recovery and Development: Perspectives from New Zealand and Australia. In Disaster and Development: Examining Global Issues and Cases; Kapucu, N., Liou, K.T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, D.; Buergelt, P.T.; Tedim, F.; McCaffrey, S. Wildfires: International perspectives on their social-ecological implications. In Wildfire Hazards, Risks and Disasters; Paton, D., Buergelt, P.T., Tedim, F., McCaffrey, S., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, D.; Buergelt, P.T.; Flannigan, M. Ensuring That We Can See the Wood and the Trees: Growing the capacity for ecological wildfire risk management. In Wildfire Hazards, Risks and Disasters; Paton, D., Buergelt, P.T., McCaffrey, S., Tedim, F., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2015; pp. 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Emergency Management Committee (AEMC)—National Bushfire Warnings Taskforce. Australia’s Revised Arrangements for Bushfire Advice and Alerts; Version 1.1; Australian Emergency Management Committee: Perth, WA, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins, M.A. Synoptic climatology of extreme fire-weather conditions across the southwest United States. Int. J. Climatol. 2006, 26, 1001–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M. A climatology of extreme fire weather days in Victoria. Aust. Met. Mag. 2006, 55, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, J.; Whitmore, J. The Handbook: Surviving and Living with Climate Change; Transit Lounge: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, R.P.; Corbin, G. A model to predict red flag warning days. In Proceedings of the American Meteorology Society Seventh Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Bar Harbor, ME, USA, 23–25 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calkin, D.E.; Cohen, J.D.; Finney, M.A.; Thompson, M.P. How risk management can prevent future wildfire disasters in the wildland-urban interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, B.W.; Bartlette, R.A.; Bradshaw, L.S.; Cohen, J.D.; Andrews, P.L.; Putnam, T.; Mangan, R.J. Fire Behavior Associated with the 1994 South Canyon Fire on Storm King Mountain, Colorado; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1998.

- Rothermel, R.C. How to Predict the Spread and Intensity of Forest and Range Fires; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1983.

- Werth, P.A.; Potter, B.E.; Alexander, M.E.; Clements, C.B.; Cruz, M.G.; Finney, M.A.; Forthofer, J.M.; Goodrick, S.L.; Hoffman, C.; Jolly, W.M.; et al. Synthesis of Knowledge of Extreme Fire Behavior: Volume 2 for Fire Behavior Specialists, Researchers, and Meteorologists; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2016.

- Fogarty, L.G. Two rural/urban interface fires in the Wellington suburb of Karori: assessment of associated burning conditions and fire control strategies. FRI Bull. 1996, 197, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES). The Effects of Pyrocumulonimbus on Fire Behaviour and Management; Government of Western Australia: Perth, WA, Australia, 2017.

- U.S. Forest Services. Six Rivers National Forest (N.F.), Orleans Community Fuels Reduction and Forest Health Project: Environmental Impact Statement; Orleans Community Fuels Reduction and Forest Health Project: Environmental Impact Statement; New Orleans, LA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes da Cruz, M. Modeling the Initiation and Spread of Crown Fires. Master Thesis, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel, R.C. Predicting Behavior and Size of Crown Fires in the Northern Rocky Mountains; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A.M. Landscape fires as social disasters: An overview of ‘the bushfire problem’. Glob. Environ. Change Pt B: Environ. Hazards 2005, 6, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D.; Miller, C.; Falk, D.A. Toward a Theory of Landscape Fire. In The Landscape Ecology of Fire; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A.M.; Mckenna, D.J.; Wouters, M.A. Landscape Fire, Biodiversity Decline and a Rapidly Changing Milieu: A Microcosm of Global Issues in an Australian Biodiversity Hotspot. Land 2014, 3, 1091–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.C.; Nost, N.C. Evaluating Prescribed Fires; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1985.

- Keeley, J.E. Fire intensity, fire severity and burn severity: A brief review and suggested usage. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2009, 18, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafer, C.J.; Noonan, M.; Macnaught, E. The post-fire measurement of fire severity and intensity in the Christmas 2001 table ASydney wildfires. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2004, 13, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecina-Diaz, J.; Alvarez, A.; Retana, J. Extreme fire severity patterns in topographic, convective and wind-driven historical wildfires of mediterranean pine forests. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollet, J.; Omi, P.N. Effect of thinning and prescribed burning on crown fire severity in ponderosa pine forests. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2002, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, S.A.; Miller, C.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Holsinger, L.M.; Parisien, M.-A.; Dobrowski, S.Z. How will climate change affect wildland fire severity in the western US? Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 35002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D.; Thode, A.E. Quantifying burn severity in a heterogeneous landscape with a relative version of the delta Normalized Burn Ratio (dNBR). Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 109, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, B.; Davies, J.; Johnston, K. Wildland Urban Interface Wildfire Threat Assessments in B.C.; Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations Wildfire Management Branch: British Columbia, Canada, 2013.

- Moritz, M.A. Analyzing Extreme Disturbance Events: Fire in Los Padres National Forest. Ecol. Appl. 1997, 7, 1252–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, W.J.; Orzell, S.L.; Slocum, M.G. Seasonality of Fire Weather Strongly Influences Fire Regimes in South Florida Savanna-Grassland Landscapes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Definition Criteria | Metrics | Bowman et al. (2017) [1] | Lannom et al. (2014) [56] | McRae (2010) [20] | McRae and Sharples (2011) [21] | Oliveri et al. (2012) [69] | Sampson et al. (2000) [54] | Weber and Dold (2006) [68] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Fire Metric | Size | + | + | + | ||||

| Duration | + | |||||||

| Impacts | Proportion of area burnt with high severity | + | ||||||

| Impacts | + | |||||||

| Fire Environment | Fuel load and structure | + | ||||||

| Wind speed | + | + | ||||||

| Wind direction change | + | |||||||

| Atmospheric instability * | + | + | ||||||

| Distance to the wildland–urban interface | + | |||||||

| Fire Behavior | Extreme phenomena ** | + | + | |||||

| Fire radiative power | + | |||||||

| Rapid evolution | + |

| Criteria | Indicators | Social Implications and Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fire behavior | FLI | ≥10,000 kWm-1 | DURING FIRE SPREAD AND SUPPRESSION Increase of the area of intervention: (i) Requires more fire suppression resources; (ii) Increases the threatened area and potential losses and damages. Response capacity of suppression crews: (i) Reorganization of suppression activities is made difficult by the increasing ROS; (ii) Deployed crews are rapidly overwhelmed. Capacity of reaction of people and displacement capacity is overwhelmed by ROS and massive spotting. Impacts: (i) Smoke problems: increased hospital admissions during and immediately after the fires; poor visibility; impacts on displacement and on the use of firefighting aircraft; (ii) Loss of lives. AFTER SUPPRESSION Short -term and long-term impacts: (i) Loss of lives and injured people; (ii) Economic damages; (iii) High severity. |

| Plume dominated event with EFB | Possible pyroCb with downdrafts | ||

| FL | ≥ 10 m | ||

| ROS | ≥ 50 m/min | ||

| Spotting | Activity Distance | ||

| Fire behavior sudden changes | Unpredictable variations of fire intensity Erratic ROS direction Spotting | ||

| Capacity of control | Difficulty of control | Fire behavior overwhelms capacity of control Fire spreads unchecked, as suppression operations are either not attempted or ineffective | DURING SUPPRESSION Immediate consequences: (i) Entrapments and fire overruns; (ii) Unplanned last moment evacuations; (iii) Entrapments with multiple fatalities and near misses; (iv) Fatal fire overruns. |

| Fire Category | Real Time Measurable Behavior Parameters | Real Time Observable Manifestations of EFB | Type of Fire and Capacity of Control * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLI* (kWm−1) | ROS (m/min) | FL (m) | PyroCb | Downdrafts | Spotting Activity | Spotting Distance (m) | |||

| Normal Fires | 1 | <500 | <5 <15 b | <1.5 | Absent | Absent | Absent | 0 | Surface fire

Fairly easy |

| 2 | 500–2000 | <15 <30 b | <2.5 | Absent | Absent | Low | <100 | Surface fire

Moderately difficult | |

| 3 | 2000–4000 | <20 c <50 d | 2.5-3.5 | Absent | Absent | High | ≥100 | Surface fire, torching possible

Very difficult | |

| 4 | 4000–10,000 | <50 c <100 d | 3.5-10 | Unlikely | In some localized cases | Prolific | 500–1000 | Surface fire, crowning likely depending on vegetation type and stand structure

Extremely difficult | |

| Extreme Wildfire Events | 5 | 10,000–30,000 | <150 c <250 d | 10-50 | Possible | Present | Prolific | >1000 | Crown fire, either wind- or plume-driven

Spotting plays a relevant role in fire growth Possible fire breaching across an extended obstacle to local spread Chaotic and unpredictable fire spread Virtually impossible |

| 6 | 30,000–100,000 | <300 | 50-100 | Probable | Present | Massive Spotting | >2000 | Plume-driven, highly turbulent fire

Chaotic and unpredictable fire spread Spotting, including long distance, plays a relevant role in fire growth Possible fire breaching across an extended obstacle to local spread Impossible | |

| 7 | >100,000 (possible) | >300 (possible) | >100 (possible) | Present | Present | Massive Spotting | >5000 | Plume-driven, highly turbulent fire

Area-wide ignition and firestorm development non-organized flame fronts because of extreme turbulence/vorticity and massive spotting Impossible | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Amraoui, M.; Bouillon, C.; Coughlan, M.R.; Delogu, G.M.; Fernandes, P.M.; Ferreira, C.; McCaffrey, S.; McGee, T.K.; et al. Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts. Fire 2018, 1, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1010009

Tedim F, Leone V, Amraoui M, Bouillon C, Coughlan MR, Delogu GM, Fernandes PM, Ferreira C, McCaffrey S, McGee TK, et al. Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts. Fire. 2018; 1(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleTedim, Fantina, Vittorio Leone, Malik Amraoui, Christophe Bouillon, Michael R. Coughlan, Giuseppe M. Delogu, Paulo M. Fernandes, Carmen Ferreira, Sarah McCaffrey, Tara K. McGee, and et al. 2018. "Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts" Fire 1, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1010009

APA StyleTedim, F., Leone, V., Amraoui, M., Bouillon, C., Coughlan, M. R., Delogu, G. M., Fernandes, P. M., Ferreira, C., McCaffrey, S., McGee, T. K., Parente, J., Paton, D., Pereira, M. G., Ribeiro, L. M., Viegas, D. X., & Xanthopoulos, G. (2018). Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts. Fire, 1(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1010009