The Influence of Graphene Oxide Concentration and Sintering Atmosphere on the Density, Microstructure, and Hardness of Al2O3 Ceramics Obtained by the FFF Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

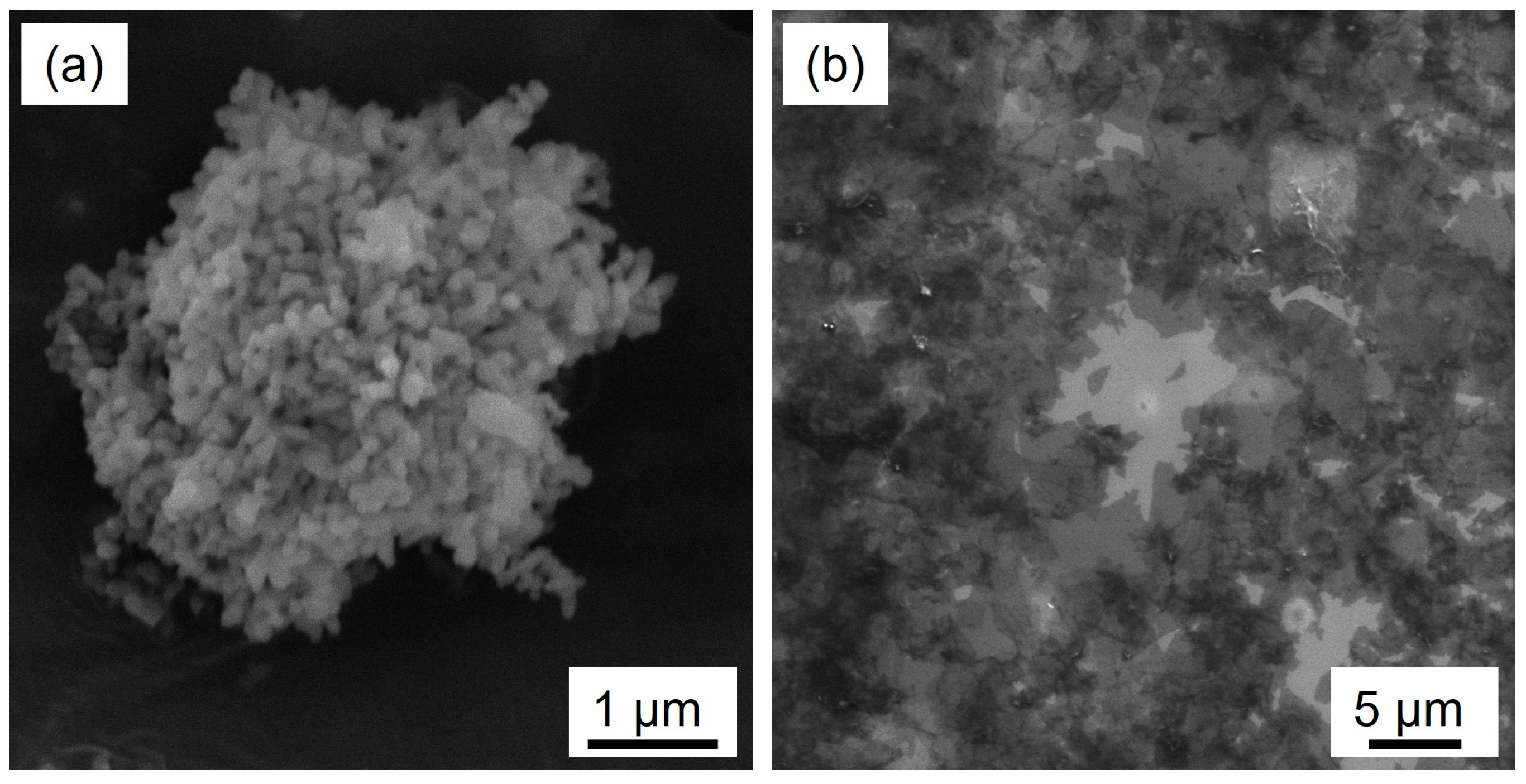

2.1. Raw Materials and Filaments Fabrication

2.2. Debinding and Sintering

2.3. Samples Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Sintered Materials

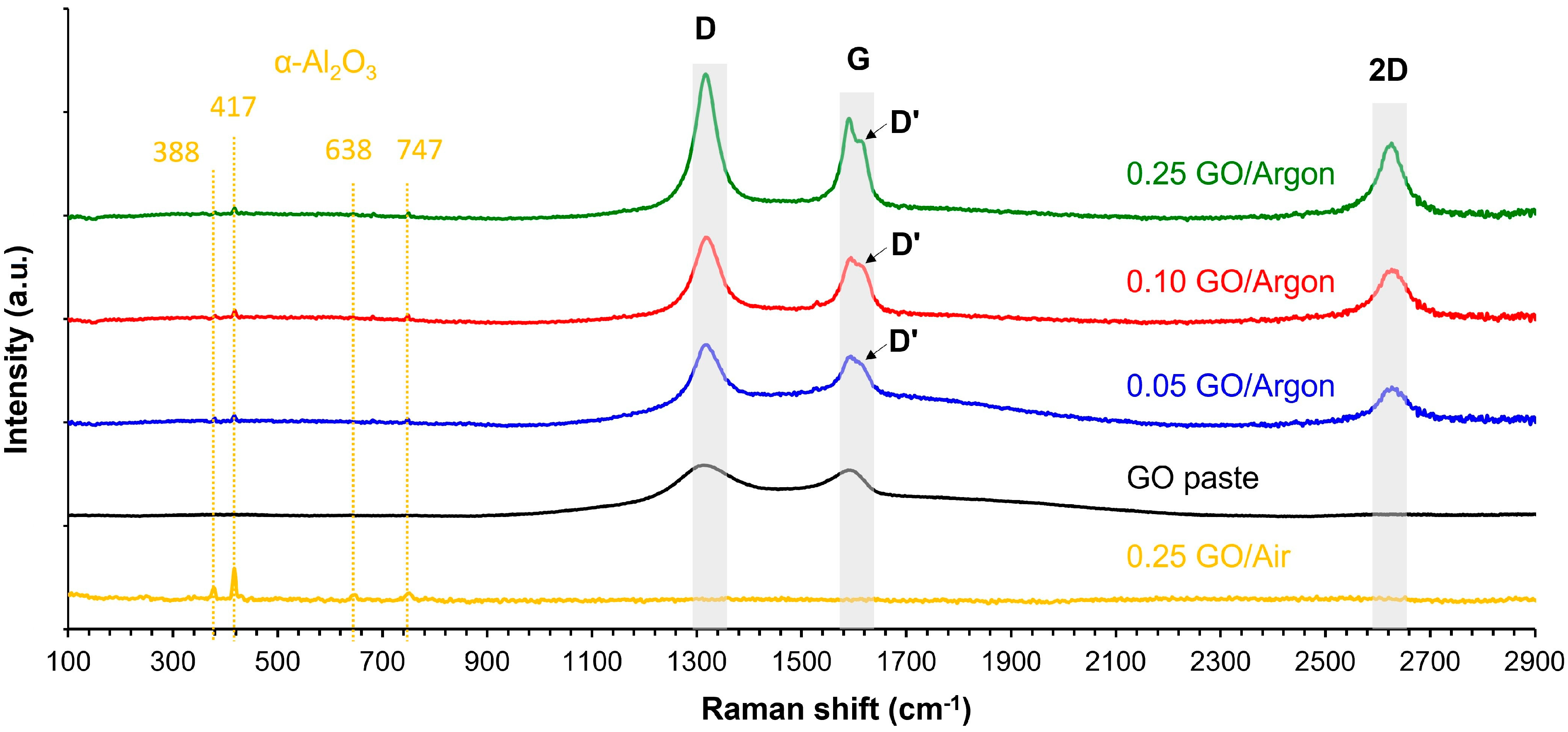

3.1.1. Raman Spectra of Materials

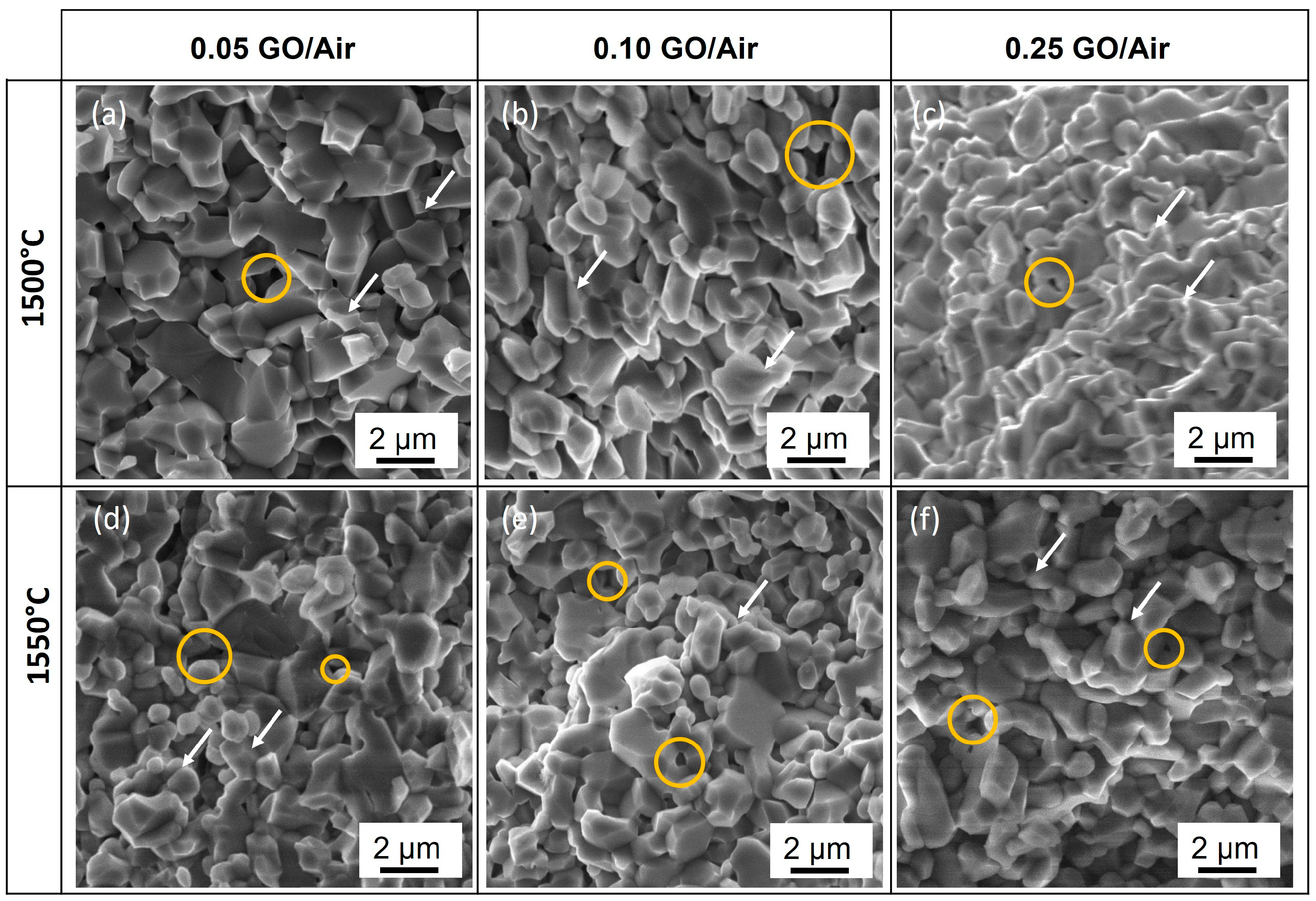

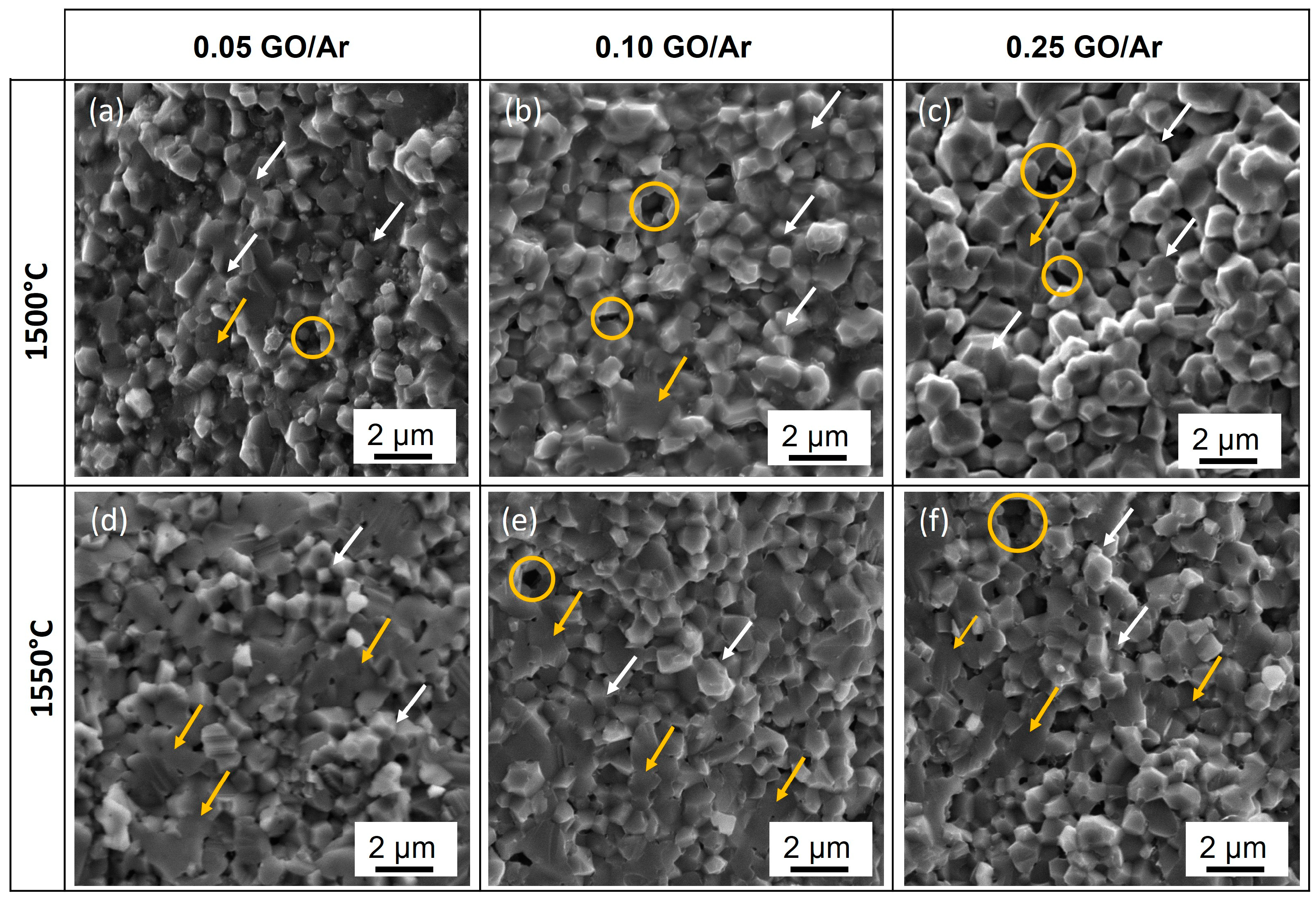

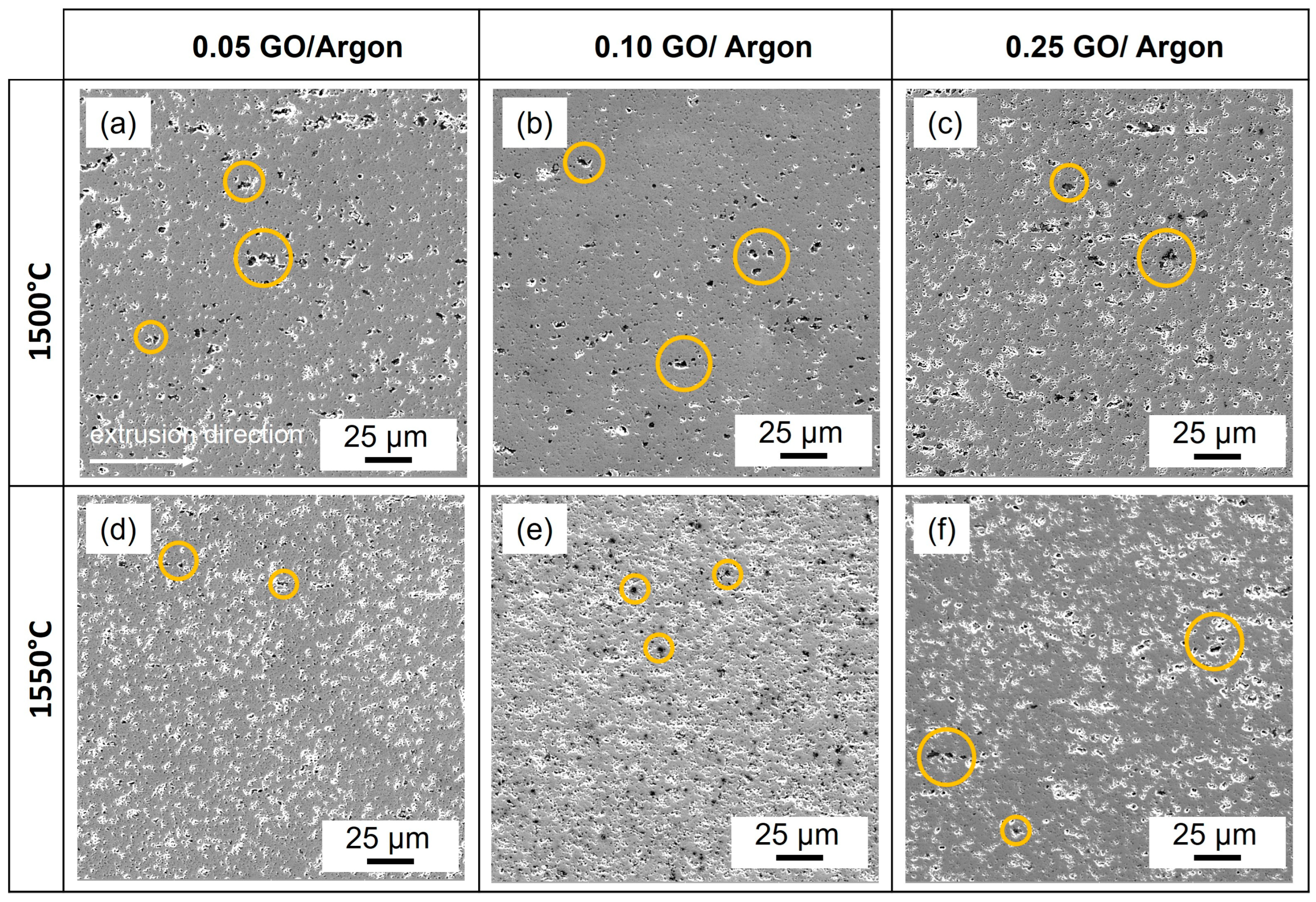

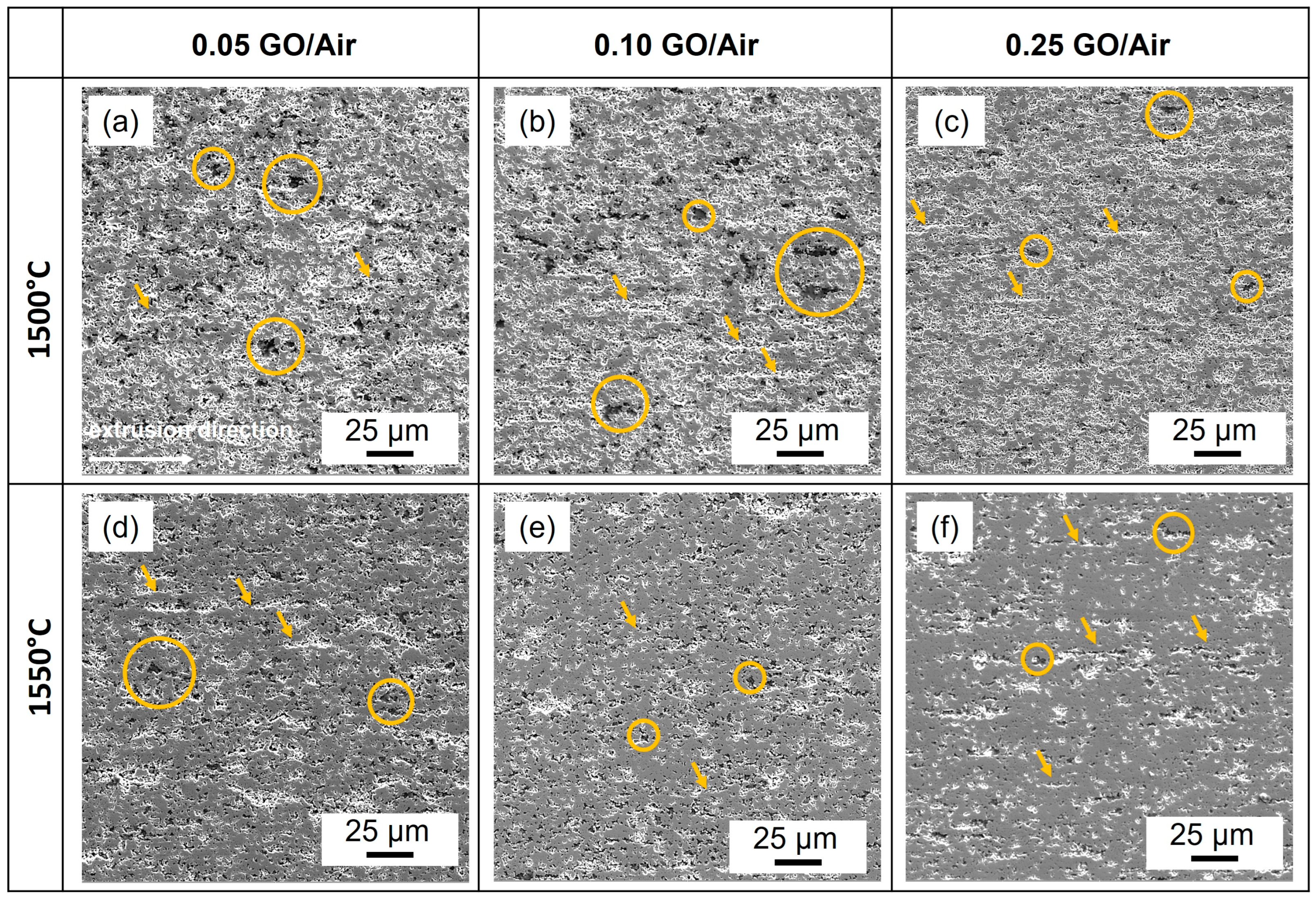

3.1.2. Microstructure of Sintering Composites

3.2. Density and Hardness of Sintering Composites

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abyzov, A.M. Aluminum Oxide and Alumina Ceramics (review). Part 1. Properties of Al2O3 and Commercial Production of Dispersed Al2O3. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2019, 60, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agac, O.; Gozutok, M.; Turkoglu, H.; Ozturk, A.; Park, J. Mechanical and biological properties of Al2O3 and TiO2 co-doped zirconia ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 10434–10441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S.; Zeeshan, M.D.; Ansari, M.I.; Sharma, D. Progress in tribological research of Al2O3 ceramics: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 82, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Yao, H.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, J. Preparation, microstructure, and properties of ZrO2 (3Y)/Al2O3 bioceramics for 3D printing of all-ceramic dental implants by vat photopolymerization. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2022, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Hu, Q. A review of Al2O3-based eutectic ceramics for high-temperature structural materials. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 214, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Bai, L.; Tian, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, F. Recent progress of thermal conductive ploymer composites: Al2O3 fillers, properties and applications. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 152, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, R.; Morfini, L. Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing of Ceramics: A Review on Filament-Based Process. Materials 2024, 17, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaytsev, A.I.; Sotov, A.V.; Abdrahmanova, A.E.; Popovich, A.A. Additive manufacturing of polymer-ceramic materials using fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology: A review. Powd. Metall. Funct. Coat. 2024, 18, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.; Taufik, M. Nanocomposite Materials for Fused Filament Fabrication. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 5142–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gutierrez, J.; Cano, S.; Schuschnigg, S.; Kukla, C.; Sapkota, J.; Holzer, C. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic and Ceramic Components by the Material Extrusion of Highly-Filled Polymers: A Review and Future Perspectives. Materials 2018, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markandan, K.; Chin, J.K.; Tan, M.T.T. Recent Progress in Graphene Based Ceramic Composites: A Review. J. Mater. Res. 2017, 32, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakchaure, M.B.; Menezes, P.L. Advances in the Tribological Performance of Graphene Oxide and Its Composites. Materials 2025, 18, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, C.; Belmonte, M.; Miranzo, P.; Osendi, M.I. Applications of Ceramic/Graphene Composites and Hybrids. Materials 2021, 14, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczak, M.; Jastrzębska, A.M. A Review on Development of Ceramic-Graphene Based Nanohybrid Composite Systems in Biological Applications. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 685014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Florez, V.; Domínguez-Rodríguez, A. Mechanical properties of ceramics reinforced with allotropic forms of carbon. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 128, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinloch, I.A.; Suhr, J.; Lou, J.; Young, R.J.; Ajayan, P.M. Composites with carbon nanotubes and graphene: An outlook. Science 2018, 362, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, E.; Smirnov, A.; Gusarov, A.V.; Solís Pinargote, N.W.; Tarasova, T.V.; Grigoriev, S.N. Influence of Graphene Oxide on Printability, Rheological and Mechanical Properties of Highly Filled Alumina Filaments and Sintered Parts Produced by FFF. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubovčáková, M.; Múdra, E.; Bureš, R.; Kovalčíková, A.; Sedlák, R.; Girman, V.; Hvizdoš, P. Microstructure, fracture behaviour and mechanical properties of conductive alumina-based composites manufactured by SPS from graphenated Al2O3 powders. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 4818–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.; Peretyagin, P.; Smirnov, A.; Solis, W.; Díaz, L.A.; Fernández, A.; Torrecillas, R. Effect of graphene addition on the mechanical and electrical properties of Al2O3-SiCw ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 37, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdova, M.; Hussainova, I.; Pérez-Coll, D.; Aghayan, M.; Ivanov, R.; Rodríguez, M.A. A novel approach to electroconductive ceramics filled by graphene covered nanofibers. Mater. Des. 2016, 90, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.; Peretyagin, N.; Apelfeld, A.; Smirnov, A.; Rybkina, A.; Kameneva, E.; Zheltukhin, A.; Gerasimov, M.; Volosova, M.; Yanushevich, O.; et al. Investigation of the Characteristics of MAO Coatings Formed on Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy in Electrolytes with Graphene Oxide Additives. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmysheva, A.Y.; Kuznetsova, E.; Vedenyapina, M.D.; Podrabinnik, P.; Pinargote, N.W.S.; Smirnov, A.; Grigoriev, S.N. Removal of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid from Aqueous Solutions Using Al2O3/Graphene Oxide Granules Prepared by Spray-Drying Method. Resources 2024, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Gonzalez, C.F.; Smirnov, A.; Centeno, A.; Fernández, A.; Alonso, B.; Rocha, V.G.; Torrecillas, R.; Zurutuza, A.; Bartolome, J.F. Wear behavior of graphene/alumina composite. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 7434–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sim, H.J.; Lu, H.; Cao, H.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, P. Effect of reduced graphene oxide on the mechanical properties of rGO/Al2O3 composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 24021–24031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczak, S.; Pietrzyk, B. Morphology and Structure of Al2O3 + Graphene Low-Friction Composite Coatings. Coatings 2022, 12, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubío, C.R.; Rama, A.; Gómez, M.; del Río, F.; Guitián, F.; Gil, A. 3D-printed graphene-Al2O3 composites with complex mesoscale architecture. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 5760–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuaje, J.; Rama, A.; Mallo-Abreu, A.; Boado, M.G.; Majellaro, M.; Tubío, C.R.; Prieto, R.; García-Mera, X.; Guitián, F.; Sotelo, E.; et al. Catalytic performance of a metal-free graphene oxide-Al2O3 composite assembled by 3D printing. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Guan, R.; Ou, K.; Fu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Li, D.S.; Sun, Y. Direct ink writing 3D printing of graphene/Al2O3 composite ceramics with gradient mechanics. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2201414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Sanabria, L.; Ramírez, C.; Osendi, M.I.; Belmonte, M.; Miranzo, P. Enhanced thermal and mechanical properties of 3D printed highly porous structures based on γ-Al2O3 by adding graphene nanoplatelets. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, L.; Bai, S. High thermal conductivity polylactic acid composite for 3D printing: Synergistic effect of graphene and alumina. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2020, 31, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, C.; Shamshirgar, A.S.; Pérez-Coll, D.; Osendi, M.I.; Miranzo, P.; Tewari, G.C.; Karppinen, M.; Hussainova, I.; Belmonte, M. CVD nanocrystalline multilayer graphene coated 3D-printed alumina lattices. Carbon 2023, 202, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanchao, G.U.; Lian, S.; Xiaoyu, J.I.; Honglei, W.; Jinshan, Y.U.; Xingui, Z. High-performance and high-precision Al2O3 architectures enabled by high-solid-loading, graphene-containing slurries for top-down DLP 3D printing. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 43, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E3220-20; Standard Guide for Characterization of Graphene Flakes. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S.; et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 187401–187404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C. Raman spectroscopy of graphene and graphite: Disorder, electron–phonon coupling, doping and nonadiabatic effects. Solid State Commun. 2007, 143, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Díaz, D.; López Holgado, M.; García-Fierro, J.L.; Velázquez, M.M. Evolution of the Raman Spectrum with the Chemical 610 Composition of Graphene Oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 20489–20497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.D.; Kim, H.T. Direct formation of graphene shells on Al2O3 nano-particles using simple thermal treatment under C2H2-H2 atmospheric conditions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 202, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, T.; Rout, T.K.; Palei, B.B.; Bajpai, S.; Kundu, S.; Bhagat, A.N.; Satpathy, B.K.; Biswal, S.K.; Rajput, A.; Sahu, A.K.; et al. Synthesis of α-Al2O3–graphene composite: A novel product to provide multi-functionalities on steel strip surface. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, R.E.; Mitchell, J.R.; Grow, R.W. Raman Scattering as a Diagnostic Technique for Cathode Characterization. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 1987, 34, 1842–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; You, J.; Canizarès, A.; Tang, X.; Lu, L.; Bessada, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, S.; Zhang, Z. Quantitative studies on the microstructure evolution and its impact on the viscosity of a molten Al2O3-Na3AlF6 system by Raman spectroscopy and theoretical simulations. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 396, 123732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Estili, M.; Igarashi, G.; Kawasakia, A. The effect of homogeneously dispersed few-layer graphene on microstructure and mechanical properties of Al2O3 nanocomposites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 34, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, A.; Rocha, V.G.; Alonso, B.; Fernández, A.; Gutierrez-Gonzalez, C.F.; Torrecillas, R.; Zurutuza, A. Graphene for tough and electroconductive alumina ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 33, 3201–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Islam, M.; Abdo, H.S.; Subhani, T.; Khalil, K.A.; Almajid, A.A.; Yazdani, B.; Zhu, Y. Toughening mechanisms and mechanical properties of graphene nanosheet-reinforced alumina. Mater. Des. 2015, 88, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, W.A.; Luo, X.; Guo, C.; Rabiu, B.I.; Huang, B.; Yang, Y.Q. Preparation and mechanical properties of graphene-reinforced alumina-matrix composites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 754, 137765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwal, H.; Tatarko, P.; Grasso, S.; Khaliq, J.; Dlouhý, I.; Reece, M.J. Ceramic. Graphene reinforced alumina nano-composites. Carbon 2013, 64, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, S.; Yanushevich, O.; Krikheli, N.; Kramar, O.; Pristinskiy, Y.; Solis Pinargote, N.W.; Peretyagin, P.; Smirnov, A. Design and Mechanical Properties of ZTA–Niobium Composites with Reduced Graphene Oxide. Ceramics 2025, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.; Pristinskiy, Y.; Pinargote, N.W.S.; Meleshkin, Y.; Podrabinnik, P.; Volosova, M.; Grigoriev, S. Mechanical Performance and Tribological Behavior of WC-ZrO2 Composites with Different Content of Graphene Oxide Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering. Sci 2024, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, W.A.; Luo, X.; Rabiu, B.I.; Huang, B.; Yang, Y.Q. Toughness enhancement and thermal properties of graphene-CNTs reinforced Al2O3 ceramic hybrid nanocomposites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 781, 138978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.-M.; Oh, Y.-S.; Yang, Y.-H.; Lim, Y.S.; Yoon, D.H.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.-Y.; Ruoff, R.S. Unoxidized Graphene/Alumina Nanocomposite: Fracture- and Wear-Resistance Effects of Graphene on Alumina Matrix. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duntu, S.H.; Hukpati, K.; Ahmad, I.; Islam, M.; Boakye-Yiadom, S. Deformation and fracture behaviour of alumina-zirconia multi-material nanocomposites reinforced with graphene and carbon nanotubes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 835, 142655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbazhagan, M.; Michael, A.X. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of graphene reinforced Alumina Ceramic matrix composite. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, E.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X. Determination of microstructure and mechanical properties of graphene reinforced Al2O3-Ti (C, N) ceramic composites. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 20593–20599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, J.; Giménez, R.; García-Juarez, A.; Berges, C.; Herranz, G. Ceramic injection moulding adequacy in the fabrication of graphene reinforced cordierite–mullite for high-temperature applications. Boletín Soc. Española Cerámica Y Vidr. 2025, 64, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusova, E.A.; Ponomarev, I.; Shelekhov, E. Effect of graphene sheets on the physico-chemical properties of nanocrystallite ceria. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 241771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.J.; Dong, P.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, J.M. Fabrication of hollow lattice alumina ceramic with good mechanical properties by digital light processing 3D printing technology. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 26519–26527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhao, T.; Dou, R.; Wang, L. Additive manufacturing of low-shrinkage alumina cores for single-crystal nickel-based superalloy turbine blade casting. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 15218–15226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Das, P.K. Microstructure and physicomechanical properties of pressureless sintered multiwalled carbon nanotube/alumina nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

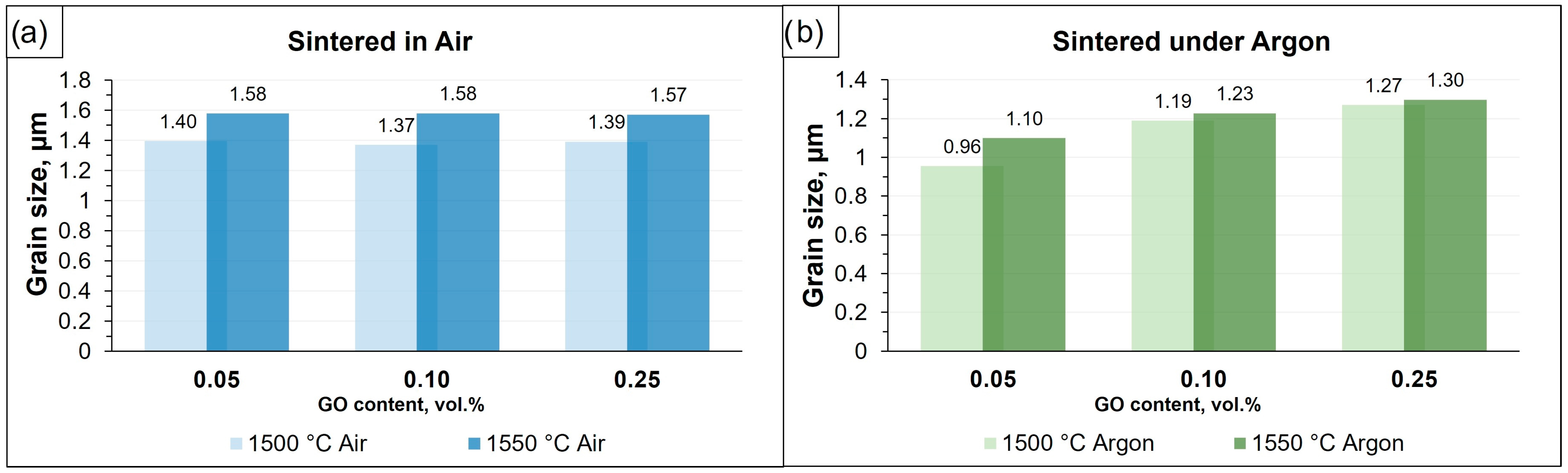

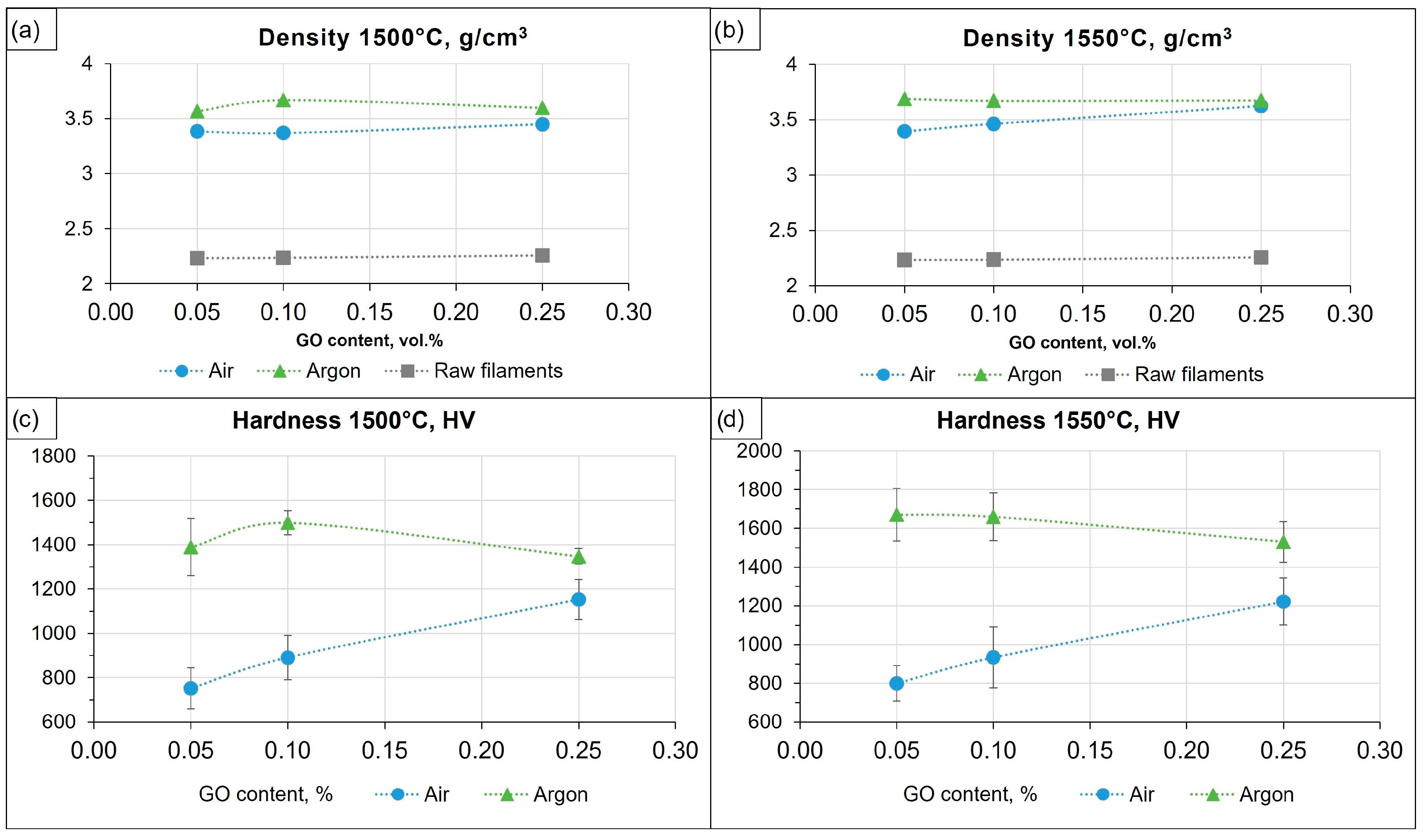

| No | Sample | Sintering Temperature, °C | Graphene Oxide Content (vol.%) | Average Grain Size (μm) | Density (g/cm3) | Hardness (HV10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.05GO/Air | 1500 | 0.05 | 1.40 ± 0.70 | 3.38 ± 0.04 | 751.57 ± 92.78 |

| 2 | 0.1GO/Air | 0.1 | 1.37 ± 0.61 | 3.37 ± 0.05 | 890.94 ± 100.67 | |

| 3 | 0.25GO/Air | 0.25 | 1.39 ± 0.57 | 3.45 ± 0.04 | 1152.65 ± 90.20 | |

| 4 | 0.05GO/Ar | 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.65 | 3.57 ± 0.06 | 1388.97 ± 128.52 | |

| 5 | 0.1GO/Ar | 0.1 | 1.19 ± 0.52 | 3.67 ± 0.04 | 1499.01 ± 53.51 | |

| 6 | 0.25GO/Ar | 0.25 | 1.27 ± 0.73 | 3.60 ± 0.03 | 1347.81 ± 34.90 | |

| 7 | 0.05GO/Air | 1550 | 0.05 | 1.58 ± 0.77 | 3.39 ± 0.05 | 800.02 ± 91.00 |

| 8 | 0.1GO/Air | 0.1 | 1.58 ± 0.71 | 3.46 ± 0.07 | 933.93 ± 157.10 | |

| 9 | 0.25GO/Air | 0.25 | 1.57 ± 0.80 | 3.63 ± 0.04 | 1222.31 ± 120.64 | |

| 10 | 0.05GO/Ar | 0.05 | 1.10 ± 0.77 | 3.69 ± 0.03 | 1670.73 ± 136.90 | |

| 11 | 0.1GO/Ar | 0.1 | 1.23 ± 0.76 | 3.67 ± 0.05 | 1659.57 ± 123.76 | |

| 12 | 0.25GO/Ar | 0.25 | 1.30 ± 0.81 | 3.68 ± 0.04 | 1529.99 ± 105.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kuznetsova, E.; Smirnov, A.; Pinargote, N.W.S.; Khmyrov, R.; Strunevich, D.; Krikheli, N.; Yanushevich, O.O.; Peretyagin, P.; Gusarov, A.V. The Influence of Graphene Oxide Concentration and Sintering Atmosphere on the Density, Microstructure, and Hardness of Al2O3 Ceramics Obtained by the FFF Method. Ceramics 2026, 9, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010002

Kuznetsova E, Smirnov A, Pinargote NWS, Khmyrov R, Strunevich D, Krikheli N, Yanushevich OO, Peretyagin P, Gusarov AV. The Influence of Graphene Oxide Concentration and Sintering Atmosphere on the Density, Microstructure, and Hardness of Al2O3 Ceramics Obtained by the FFF Method. Ceramics. 2026; 9(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuznetsova, Ekaterina, Anton Smirnov, Nestor Washington Solís Pinargote, Roman Khmyrov, Daniil Strunevich, Natella Krikheli, Oleg O. Yanushevich, Pavel Peretyagin, and Andrey V. Gusarov. 2026. "The Influence of Graphene Oxide Concentration and Sintering Atmosphere on the Density, Microstructure, and Hardness of Al2O3 Ceramics Obtained by the FFF Method" Ceramics 9, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010002

APA StyleKuznetsova, E., Smirnov, A., Pinargote, N. W. S., Khmyrov, R., Strunevich, D., Krikheli, N., Yanushevich, O. O., Peretyagin, P., & Gusarov, A. V. (2026). The Influence of Graphene Oxide Concentration and Sintering Atmosphere on the Density, Microstructure, and Hardness of Al2O3 Ceramics Obtained by the FFF Method. Ceramics, 9(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010002