1. Introduction

Archaeological, historical, and artistic monuments represent economic resources for a country, just like its natural resources. Therefore, the measures taken to protect, preserve, and appropriately utilize them are not only related to development plans but should also be an integral part of them [

1].

The activities carried out by UNESCO testify to how humanity has progressively sought to understand how culture can strengthen our sense of identity. First, there emerged an awareness of the need to protect cultural heritage from the destruction seen after the end of World War II; then, there was the launch of international campaigns to safeguard archeological sites that are considered World Heritage, followed by the development and integration of the concept of intangible heritage; and finally, the focus shifted to the importance of the creative economy and the necessity of maintaining cultural jobs and the livelihoods of those engaged in such economic activities [

2].

The proper management, preservation, and protection of both tangible and intangible cultural heritage, along with creativity, are resources that require special attention. They can serve as drivers and enablers to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially when cultural solutions are employed that ensure the success of actions aimed at reaching these objectives [

3].

In the Latin American context, cultural heritage is significantly manifested through archeological sites, many of which are linked to the Inca civilization. The importance of these sites lies not only in their historical and esthetic value but also in their capacity to offer a profound understanding of the worldviews of ancient cultures. These spaces are not mere remnants of the past; they are living testimonies of traditions, beliefs, and practices that have influenced the cultural identity of contemporary communities [

4] (

Figure 1).

The Andean worldview, particularly that of the Inca civilization, has a profound connection with nature, the sacred, and the cosmos. For the Incas, the world was not divided between the material and the spiritual; both aspects interrelated and complemented each other. The earth, represented by Pachamama, was seen as a living and sacred entity, deserving of respect and care. This understanding of the world was reflected in architecture, agricultural practices, and festivals, which were designed to maintain balance between humans and the universe [

5].

In this sense, the Qhapaq Ñan, the vast Inca road network, not only facilitated mobility and cultural exchange but also connected the various regions of the empire to sacred sites and rituals dedicated to Andean deities, creating a web of spiritual and physical relationships that maintained the cohesion of the empire. The Incas believed that mountains, rivers, and other natural elements had a divine presence, and so many of these spaces were considered sacred and required specific ritual practices. The study and preservation of the remnants of this worldview in archeological sites like Machu Picchu, Ollantaytambo, and Ankasmarka not only offer a glimpse into the past but also allow us to understand how these beliefs continue to influence contemporary communities, serving as a pillar of identity and an approach to sustainability [

6].

The archeological sites of Peru, one of the main cradles of the Inca civilization, are essential for understanding the rich Inca cultural heritage. Archaeological centers such as Machu Picchu, one of the world’s wonders, stand out not only for their impressive architecture but also for reflecting the complex social, political, and religious interactions of the Andean peoples. These sites, designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, are a testament to an Andean worldview that integrated the natural and spiritual environment into the daily lives of its inhabitants [

7].

The Inca cultural network consisted of the roads and routes that formed part of the Qhapaq Ñan, a vast system of roads with architectural structures that enabled better territorial control and management of resources for the Incas. It spanned six Andean countries—Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile—and was a network of routes that connected every corner of the Inca Empire, known as Tawantinsuyu, which means “four united regions” [

8]. This empire was divided into four suyus—Chinchaysuyu in the north, Antisuyu in the east, Kuntisuyu in the west, and Qollasuyu in the south—integrating diverse cultures and traditions [

9]. The Qhapaq Ñan roads were crucial for the interconnection of these centers, facilitating the movement of people, goods, and ideas, and were essential for the administration of the empire, allowing the mobilization of armies and cultural exchange between regions. These pathways served practical purposes and were imbued with spiritual meaning, connecting the Incas with their deities and the natural environment, thereby reinforcing the cultural cohesion and identity of Tawantinsuyu [

10] (

Figure 2).

Cusco, recognized as the capital of the Inca Empire, stands as a focal point of Inca history in South America [

11]. In addition to Machu Picchu, the region is home to several sites of significant historical and archaeological importance:

Ollantaytambo: this site is notable for its defensive architecture and agricultural terraces, which demonstrate the advanced hydraulic engineering and agricultural knowledge of the Incas.

Moray: known for its amphitheater-shaped terraces, Moray served as an agricultural laboratory where experiments were conducted with various crops, utilizing the microclimatic variations at different altitudes.

Salineras de Maras: this complex stands out for its ancient techniques of salt extraction, employing an evaporation system in pools that has been preserved since pre-Inca times, offering insight into the economic and social practices of the era.

Chinchero: tecognized for its agricultural terraces and rich textile production, Chinchero is a significant example of the continuity of cultural traditions through the centuries, highlighting the skill in weaving techniques.

Pisac: This site includes an ancient astronomical observatory and a traditional market, providing evidence of the importance of astronomy in the daily life of the Incas, as well as its legacy in the local economy.

Calca: famous for its hot springs, Calca offers additional context regarding the wellness and health practices of pre-Hispanic populations.

Ankaschmarca: an archeological center with important architectural remains that enrich our understanding of Inca urbanization and its relationship with the natural environment [

12] (

Figure 3).

Ankasmarka, located in the Calca district, Cusco region, Peru, is an archeological site that provides valuable insight into the cultural, economic, and social dynamics of pre-Hispanic Andean societies. Situated at an altitude of approximately 3850 m above sea level, this site is distinguished by its complex stone structures and innovative agricultural terraces, elements that reveal a high level of architectural development and a deep understanding of agricultural engineering [

13].

Archaeological research has shown that Ankasmarka was an important administrative and ceremonial center during the Inca period, as well as a site of continuous occupation dating back to pre-Inca times. The discovery of artifacts, including pottery, lithic tools, and animal remains, has enabled the reconstruction of the economic and social practices of its inhabitants, as well as their interactions with other Andean cultures [

12]. These findings suggest that Ankasmarka was not only a focal point in the region’s social organization but also a node in the trade networks that connected different areas of the empire [

14].

The significance of Ankasmarka within the Peruvian archeological context has led to its inclusion in conservation and research programs, emphasizing the need to preserve this heritage for future studies. As new investigations are conducted, Ankasmarka will continue to contribute valuable knowledge about the complexity of cultural interactions and social organization in Andean civilizations, thus enhancing our understanding of the pre-Hispanic history of the region [

15] (

Figure 4).

The study of the Andean worldview at the archaeological site of Ankasmarka, located in the Cusco region of Peru, is essential for understanding the cultural, ritual, and economic dynamics that defined pre-Hispanic societies. Ankasmarka provides a favorable context to investigate how beliefs and spiritual practices influenced the daily lives of its inhabitants. The Andean worldview, which emphasizes the interrelationship between humans, nature, and the sacred, is reflected in social organization and agricultural practices, as evidenced by the archeological findings at the site. The Andean worldview is not merely a set of religious beliefs but a system that integrates knowledge of nature, astronomy, and cosmic forces, where deities are deeply connected to sacred landscapes such as mountains and bodies of water, which structure and order the life of Andean peoples [

15].

In the Andean worldview, time and space are not linear, but cyclical and dynamic, being deeply linked to the rhythms of nature and the communal relationships that sustain the balance of the cosmos [

16]. The Andean worldview conceived of the world as a harmonious set of relationships between humans, gods, and nature. Each element played a vital role, and deities were manifestations of natural forces that required reciprocity to maintain cosmic balance [

17].

Research has shown that ritual activities were deeply connected to agricultural cycles. For example, studies conducted in the Cusco region have observed that around 70% of agricultural festivals are related to the cultivation cycle and the veneration of deities associated with the earth, such as Pachamama [

15]. This pattern highlights the importance of spirituality in economic production and the sustainability of Andean communities.

However, the study of the Andean worldview in general, and specifically at Ankasmarka, faces significant challenges. The lack of funding for systematic research limits data collection and site preservation. It is estimated that more than 50% of archeological sites in Cusco lack detailed studies and proper conservation, which jeopardizes cultural heritage [

18]. Furthermore, urbanization and tourism development threaten the integrity of Ankasmarka, increasing pressure on natural resources and hindering the continuity of cultural traditions [

19].

To address these issues, it is crucial to implement education and awareness programs that highlight the importance of the Andean worldview and its relevance today. These programs can contribute to a sustainable approach that respects local traditions and promotes the conservation of cultural heritage [

17].

Cultural heritage not only has intrinsic value related to identity and historical memory but also plays a key role in sustainable development. In this sense, its preservation and promotion can significantly contribute to several of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially those related to poverty reduction, promoting quality education, environmental protection, decent employment, and economic growth. Both material and immaterial cultural heritage offer a unique opportunity to create economic development based on the appreciation of history, culture, and local traditions, while respecting the natural environment and fostering social cohesion [

20].

One of the clearest examples of this connection is seen in the sustainable management of archeological sites, such as the Incan centers in Peru, which are not only a source of cultural pride but also a foundation for the development of responsible tourism. When cultural tourism is properly managed, it can generate local jobs, improve infrastructure, and contribute to the regional economy without compromising the integrity of the sites. Moreover, the integration of the Andean worldview into education and sustainable practices of the communities living in these areas can foster a harmonious relationship with nature, thus promoting the protection of natural resources and community well-being [

21].

In conclusion, studying the Andean worldview at Ankasmarka is essential, not only for archeology, but also for promoting a deeper understanding of the relationship between humans and their environment. The conservation and study of this site are fundamental to ensuring that future generations appreciate and comprehend the rich cultural heritage of the Andean peoples.

This article aims to provide a detailed description of the archaeological site from both a spatial and functional perspective, with the goal of establishing a solid foundation for future research in various fields. These include the formal and structural analysis of the constructions, as well as the study of the social and political dynamics that shaped the organization and functioning of this center during the Inca period. By delving into these aspects, the objective is not only to gain a deeper understanding of the site’s material structure but also to explore how social interactions, political hierarchies, and cultural practices influenced the development and sustainability of the settlement.

3. Results

The first occupation of the Ankasmarka site dates to the Late Intermediate Period, consisting of a pre-Inca (Killke) settlement from approximately the year 800 AD. This was followed by a second occupation corresponding to the Late Horizon or Inca period, during which it is inferred that a large population resided permanently throughout the Qhochoq Valley, with an agricultural economy based on irrigation management [

33]. This archeological site is a llaqta established during the Late Intermediate Period and occupied throughout the Late Horizon, located along the Inca road between Calca and Lares [

34].

The monumental pre-Hispanic settlement in this micro-basin is the architectural complex of Ankasmarka, which is over 1200 years old [

35]. Due to its strategic location, Ankasmarka served political control functions over the Vilcanota and Lares valleys, establishing productive areas with architecture aimed at social and economic control, in addition to being an important administrative and religious center of the Inca Empire, as evidenced by the meticulous layout of its buildings and its role as a key node in the empire’s communication network [

36]. The agricultural terraces on the mountain slopes demonstrate the Incas’ mastery of mountain agriculture, reflecting their respect for the land and their ability to adapt to the environment [

37].

The archeological site includes impressive agricultural terraces as well as ceremonial and residential structures, along with other architectural features such as streets, ramps, staircases, and open spaces like plazas and courtyards [

33]. The archeological enclosures at Ankasmarka are built using stone slab (schist) masonry, bound with mud mortar and gravel in a rustic masonry style. The circular enclosures have simple masonry made of amorphous stones, with access openings built from slate stones in convex shapes [

34,

36] (

Figure 12). Currently, the Ministry of Culture is carrying out restoration and valorization actions at the Ankasmarka Archaeological Zone, which has suffered structural deterioration in the walls of the enclosures [

37].

The archeological site of Ankasmarka is organized into three sectors: A, B, and C. Sector C has been designated as a reserve zone, where archeological interventions and excavations are minimal, to preserve the cultural heritage and allow research in a more natural context. Ankasmarka contains a total of 480 identified enclosures, which feature various architectural configurations, such as elliptical, ovoid, semicircular, and rectangular shapes. These structures are constructed in a manner that adapts to the topography of the area, demonstrating the builders’ deep knowledge of the environment. The arrangement of the enclosures follows an ideological and cultural criterion, reflecting the beliefs and practices of the societies that inhabited this Andean region [

38] (

Figure 13).

The enclosures are interconnected by narrow passages, suggesting meticulous planning and a functional approach to space. The distribution of these structures is not orthogonal, indicating an organic design that integrates enclosures, retaining walls, and containment walls [

39].

3.1. Typological Analysis of the Enclosures of the Archaeological Center of Ankasmarkas

3.1.1. Viewpoint

Its strategic location allowed the inhabitants of the site, and possibly the Inca administrators, to observe the surrounding routes and landscapes, thus giving it a symbolic character related to the Andean worldview, where the hills and the territory were considered sacred. The Mirador Enclosure, like other structures at Ankasmarka, reflects the planning and spatial vision of the Incas, who not only built for practical purposes but also with symbolic and ceremonial intent.

The enclosure is rectangular, with an approximate surface area of 34 m2. For the construction of the foundations and walls, slate-like schist stone slabs were used, along with some dressed stones and others in their natural state. The construction technique employed was ordinary masonry, characterized by discontinuous rows and irregular joints, laid horizontally with gravelly clay mortar. Inside the enclosure, the patana (platform) rises between 0.30 m and 0.80 m above the rocky outcrop, featuring a uniform distribution of rounded stones placed horizontally. This elevation serves to level the interior floor’s slope and is considered a recurring pattern in the constructions of the Ankasmarka archeological site; it was also used as a resting bed.

The floor consists of earth mixed with clay. Adjacent to the patana is a semicircular bench, which displays sizable lithic elements at its head. This structure may have also functioned as a ventilation duct and was used as seating.

This enclosure is unique in its rectangular shape and holds a strategic location, offering a panoramic view of the entire Qochoq Valley and its surroundings (

Figure 14).

3.1.2. Dwelling

The shape of the structure is an irregular ovoid, with an approximate area of 26 m2. For the construction of the foundations and walls, schist stone slabs were used, along with some squared stones and others in their natural form. The technique employed was ordinary masonry, characterized by discontinuous rows and irregular bonding, laid horizontally with mortar made of clay mixed with gravelly clay.

The structure features a platform with an even distribution of rounded stones arranged horizontally. This platform, raised between 0.30 m and 0.80 m above the rocky outcrop, was designed to level the interior floor’s unevenness. This feature is recurrent in the constructions of the Ankasmarka archeological site and was used as a resting surface. The floor of the structure consists of earth mixed with clay.

Adjacent to the platform, there is a semicircular bench, where large lithic elements cover the head of the bench. This structure may also have functioned as a ventilation duct and was used as seating.

At the entrance of the structure, there is a hearth, used for cooking food and dyeing wool in the workshops. Next to the access opening, there is a circular storage container, which served to store food products and/or plants.

Additionally, the small rooms (cajuelas) have a crescent shape, with a width of 0.25 m, a height of 0.18 m, and an approximate depth of 0.26 m. Inside the structure, a “U”-shaped feature was found, with a width of 0.48 m, a length of 1.00 m, and an average height of 0.30 m (

Figure 15).

The structure has an irregular circular shape and an approximate area of 28 m2. For the construction of the foundations and walls, slate stone slabs were used, along with some dressed stones and others in their natural form. The technique employed was ordinary masonry, characterized by discontinuous rows and irregular bonding, laid horizontally with a mortar made of clay mixed with gravelly clay.

The “patana” (stone base) presents an even distribution of rounded stones arranged horizontally, and it rises between 0.30 m and 0.80 m above the rocky outcrop, which helps to level the interior floor’s unevenness. This feature is recurrent in the constructions of the Ankasmarka archeological site and was used as a resting platform.

The floor consists of earth mixed with clay. Adjacent to the “patana”, there is a semicircular bench, where large lithic elements cover its head. This structure is also considered a possible ventilation duct and was used as seating.

At the entrance of the structure, there is a hearth, which served for both food preparation and for dyeing wool in workshops. Near the access opening, there is a circular storage pit that functions as a warehouse for foodstuffs and plants.

Finally, the “cajuelas” (small rectangular or crescent-shaped depressions) are crescent-shaped, with a width of 0.25 m, a height of 0.18 m, and an approximate depth of 0.26 m (

Figure 16).

The structure, shaped like a “D” and covering an approximate area of 29 m2, was constructed using slate schist stone slabs. For the foundation and wall construction, the technique of ordinary masonry was employed, combining discontinuous rows and irregular bonding, all set with a mortar made of clay mixed with gravelly clay. This construction technique is characteristic of the region and ensures the stability and durability of the structure.

The platform is raised between 0.30 m and 0.80 m above a rocky outcrop, which helps to level the interior floor of the structure. This area is composed of an even distribution of cobblestones laid horizontally and was used as a resting bed. This feature is recurrent in the constructions of the Ankasmarka archeological site, suggesting continuity in the building practices of the region. The floor of the structure is made of earth mixed with clay, providing a natural and durable surface. The semicircular bench, attached to the platform, displays sizable lithic elements at its head. This structure could also have functioned as a ventilation duct, in addition to serving as seating for the occupants of the structure.

The hearth, located at the entrance of the structure, had a multifunctional purpose, being used both for food preparation and for wool dyeing in workshops. Adjacent to the access opening is a circular storage pit, which serves as a repository for food products and plants, indicating the importance of food in the daily life of its inhabitants. The crescent-shaped storage niches have a width of 0.25 m, a height of 0.18 m, and a depth of approximately 0.26 m, reflecting the attention to detail in the construction of this structure. This typology is characterized by its adaptation to the topography of the land, giving it its distinctive “D” shape, revealing an understanding of the natural environment by its builders, and a design that harmonizes with the landscape (

Figure 17).

3.1.3. Workshop

The shape of the structure is an irregular oval, and the structure has an approximate area of 25 m2. For the foundations and walls, slate-like schist stone was used in slabs, along with some dressed stones and others in their natural form. The construction technique employed was ordinary masonry, characterized by discontinuous rows and irregular bonds, laid horizontally with a mortar made of clay mixed with gravelly clay.

The patana shows the even distribution of river-rounded stones in a horizontal position and rises between 0.30 m and 0.80 m above the rocky outcrop, leveling the interior floor’s unevenness. This feature is a recurring pattern in the construction of the Ankasmarka archeological site. The floor is composed of earth mixed with clay.

The bench, seemingly semicircular, is attached to the patana and features large lithic elements covering its head. Its structure may have also served as a ventilation duct. The hearth, located at the entrance of the structure, was used for food preparation and wool dyeing in the workshops.

Adjacent to the access opening is a circular deposit, which functioned as a storage space for food products and/or plants. The cajuelas are crescent-shaped, with a width of 0.25 m, a height of 0.18 m, and a depth of 0.26 m. Additionally, the niches located halfway up the wall served as supports for placing looms.

These types of structures were used for specialized activities and are associated with a large courtyard, alongside structures dedicated to storage (

Figure 18).

3.1.4. Warehouse

The enclosure has an irregular ovoid shape and an approximate area of 25 m2. The foundations and walls were constructed using slate schist stone in flagstones, along with some squared stones and others in their natural form. The construction technique employed was ordinary masonry, with discontinuous courses and irregular bonding, laid horizontally with a mortar made of mud mixed with gravelly clay.

The platform exhibits an even distribution of rounded stones in a horizontal position and is elevated between 0.30 m and 0.80 m above the rocky outcrop, which helps to level the interior floor’s unevenness. This characteristic is observed as a recurring pattern in the structures of the Ankasmarka archeological site. The floor of the enclosure is composed of earth mixed with clay.

Adjacent to the platform, there is a bench with an apparently semicircular shape, featuring large lithic elements at its head. This structure may also function as a ventilation duct. The troughs are crescent-shaped, with a width of 0.25 m, a height of 0.18 m, and a depth of 0.26 m.

This type of enclosure is typically associated with a small courtyard and is located next to spaces used for workshop activities (

Figure 19).

3.1.5. Tomb

The structure has an irregular circular shape and covers an approximate area of 12 m2. The construction of the foundations and walls utilized slate-like schist stone slabs, along with some dressed stones and others in their natural form. The construction technique employed was ordinary masonry, characterized by discontinuous rows and irregular bond patterns, which were set horizontally using a mortar made from clay mixed with gravelly soil.

The patana, a distinctive feature of this structure, displays an even distribution of rounded stones arranged horizontally. This feature creates an elevated space ranging from 0.30 m to 0.80 m above the rocky outcrop, allowing for the leveling of the floor’s unevenness inside the structure. This design is a recurring pattern in the constructions of the Ankasmarka archeological site, where the patana was used for religious offerings.

As for the floor, it consists of earth mixed with clay, which gives the structure a rustic and functional appearance. It is important to note that the rooms are small in size and are mostly associated with funerary activities, reflecting their cultural and ceremonial significance in the region (

Figure 20).

3.2. Analysis by Sectors

3.2.1. Sector A

It is located in the southern part of the Archaeological Zone, consisting of 85 enclosures, which are built on artificial platforms and situated on a rocky slope [

33]. The plans of the enclosures are semicircular and elliptical in shape, with one enclosure having a rectangular plan. The structures are formed by octagonal angles with simple masonry, composed of slate slabs and dressed stones. This area is associated with a courtyard and is strategically positioned with a privileged view of the entire Qochoq Valley and the surrounding mountains.

Sector A consists of more than 100 enclosures, situated on artificial platforms and positioned on the sloping rocky terrain. The enclosures are associated with funerary structures, retaining walls, and small passageways, along with two possible ceremonial slabs. These features are located on the ridge that borders the cliff [

28] (

Figure 21).

3.2.2. Sector B

This sector is located on a steep slope. The structures are distributed across a rugged and rocky topography, with terraces at the lower part forming platforms resembling agricultural terraces. Both inside and outside, the structures exhibit a conical, almost round shape.

The southern zone has a less rugged topography compared to the other sectors. It consists mainly of structures attached to a rocky outcrop, with more than 80 rooms. Each one features patanas (stone-built platforms) and narrow passages, which are properly equipped with stairways. The buildings are placed on retaining and containment walls, integrated into artificial platforms that follow the morphology of the terrain. The northern zone is located in the most rugged area, where the ground is predominantly rocky. The construction of the rooms here adapts more irregularly to the area’s topography, though with less intensity than in the southern zone. This sector is characterized by the presence of cracks in the rocks, suggesting the existence of possible tombs, as evidenced by human remains. In total, there are 173 rooms in Sector B [

28] (

Figure 22).

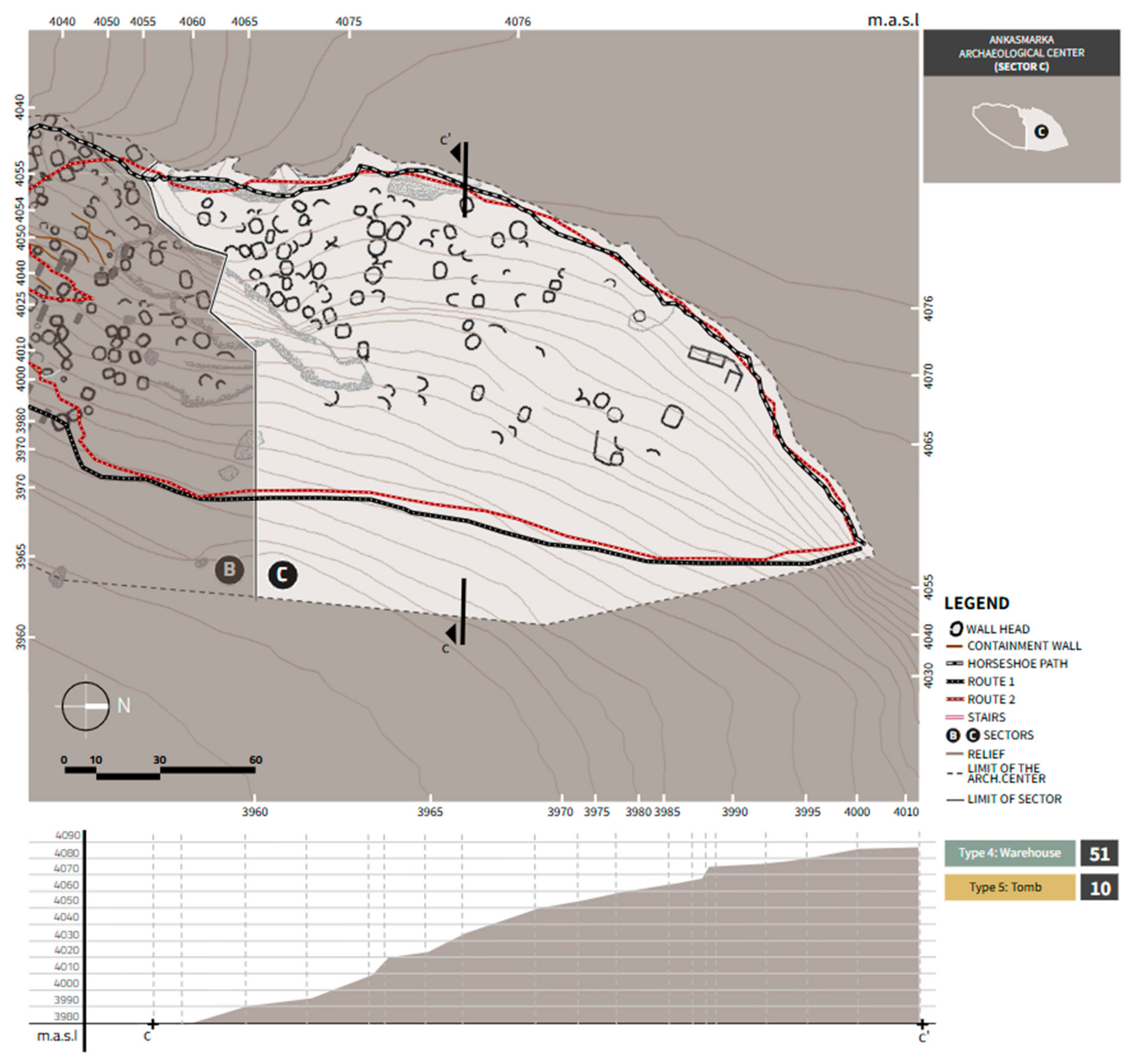

3.2.3. Sector C

This sector is located in the upper part of the northern side and comprises 140 plant enclosures, 61 of which have been identified. These enclosures exhibit irregular semicircular and rectangular shapes [

33]. In total, 36 semicircular plant enclosures can be identified, with their openings oriented in accordance with the topography of the area. Many of these enclosures are associated with tombs located in rock crevices, suggesting a significant relationship between the funerary and residential spaces.

In this sector, enclosures are distributed across topographies with less slope compared to the two previous sectors. The masonry is simple, although in some buildings, semi-worked dressed stones are visible, especially at the corners, the jambs of openings, and niches, forming part of the structural binding. Despite these details, it is important to note that this sector has not yet been subject to a detailed study [

35]. This indicates significant potential for future research that could provide a deeper understanding of its architecture and historical context (

Figure 23).

4. Discussion

There were various opinions regarding the function of the structures found at the Ankasmarka archeological site due to the presence of interior platforms in these buildings. The possibilities of these structures being built for rest, storage, or even spinning activities were never dismissed, since, like Machu Picchu or Saqsaywaman, Ankasmarka was part of the Qhapaq Ñan route, with its primary function being storage. Similar to these other sites, it was constructed on platforms to adapt to the prominent slope of the terrain; however, Ankasmarka would ultimately be located at the highest point in the Calca province, rather than in its foothills [

40].

Based on the archeological evidence found and recorded, it can be determined that the Ankasmarka Archaeological Zone was a settlement, or llacta, that lived in constant conflict. It is clear that within the Ankasmarka Archaeological Zone, we find a combination of local and regional production centers, along with complex commercial exchange interactions. The ceramic objects studied are predominantly domestic items, such as plates or pukus of various sizes. The lithic materials include domestic tools (grinding stones, tunahuas, mortars, pestles, mace clubs, projectile points, lithic elements in the process of manufacture, and yunkes). Additionally, there is a wide variety of combat tools, which suggest the function of Ankasmarka as a site for military activity [

41].

Ankasmarka was probably a center for the storage and distribution of resources, particularly camelids, as evidenced by the storage structures found at the site [

38]. Ankasmarka may have served as a storage center for the surrounding populations, facilitating the distribution of these resources to other areas of the Sacred Valley and beyond. This storage function is crucial for understanding the role of Ankasmarka within the Inca economic system. The site likely had both productive and logistical functions, aimed at facilitating the social and economic organization of the area through the management of resources for the sustenance of the local population, with significant connections to the broader distribution network of the Inca Empire.

During the Late Intermediate Period, community storage practices began to emerge in settlements as part of a local maize production process, supplemented with beans, tubers, and fish, driven by the population of the valleys and pre-Andean foothills [

39]. The archeological center is located in an ecological zone dedicated to livestock and agriculture. Ankasmarka adapted to the topography by creating large cultivation platforms, becoming a center dedicated to trade, similar to many centers located along the Inca road, such as Pauca Alto in Canta, which was also dedicated to the collection and storage of agricultural and livestock resources in the pre-Hispanic Andes, a practice that dates back several centuries before the Inca state [

40].

According to architectural analysis and 3D surveys conducted at Ankasmarka, its architectural structure shows notable similarities with the Kuelap site in the Amazon. Both areas share characteristics, such as a distinctive architectural technique; the use of cyclopean masonry, involving large stone blocks without mortar, to create robust and resistant walls; circular or oval-shaped buildings, commonly found in both centers, particularly in structures intended for ceremonial or administrative purposes; a strategic relationship with the landscape, with both sites situated in mountainous areas, providing an excellent vantage point and control over the surrounding territories; and administrative and ceremonial functions, with both sites used to store resources and organize activities related to administration. However, it is important to note that geographical and cultural differences also led to significant distinctions between the two sites.

5. Conclusions

The functional analysis of the Ankasmarka archeological site reveals significant complexity in its structure and organization, reflecting a rich cultural and social history. The archeological area consists of various sectors, each with specific characteristics and functions, suggesting careful planning and the efficient use of space.

In Sector A, although fewer enclosures are observed due to its location on the edge of a cliff, key elements such as kanchas, circulation passages, and possible courtyards are identified, indicating a functional design. This sector, despite its limited enclosures, appears to have had a specific role within the overall organization of the site.

On the other hand, Sector B stands out as the area with the highest concentration of enclosures and has undergone a meticulous restoration process. Agricultural terraces are visible here, suggesting a strong connection to agricultural practices and an economy based on crop production. The near-complete restoration of this sector allows for an appreciation of the complexity of its design and functionality, as well as its importance in the daily life of the ancient inhabitants.

Finally, Sector C represents the largest area and contains the greatest number of enclosures associated with tombs. Its gentler slope and the presence of terraces constructed with retaining and containment walls suggest the effective use of the terrain, adapting to the topography and maximizing available space for funerary and residential activities.

Additionally, other areas of interest have been identified, such as the tombs on the western side of the Cerro de Ankasmarka and the buried structures on the eastern part of Sector A. The findings from the 2010 archeological rescue work along the Calca–Qellopuyto road, which revealed drying platforms for products such as potato derivatives and charqui (dried meat), emphasize the diversity of activities carried out at the site. The favorable climatic conditions provided by the confluence of ravines allowed for the preservation and dehydration of food, such as chuño (freeze-dried potato) and corn, adding a functional and economic dimension to the analysis of the site.

It is important to highlight that many of the enclosures had a multifunctional role, serving not only as sleeping quarters but also as kitchens and storage spaces for agricultural products and clothing.

In conclusion, Ankasmarka is not only a testament to the architectural skill of its builders but also a reflection of the interrelationship between the environment, agriculture, and funerary practices. This site, in addition to being an administrative and religious space, was predominantly domestic, being largely dedicated to pastoral and agricultural activities, as well as to the production of clothing made from the fibers of South American camels. The richness of its structure and functionality invites further research to deepen our understanding of its history and its role within the civilization that inhabited it.

In conclusion, the functional analysis of Ankasmarka provides evidence that this archeological center was not only a space for storage and administration but also an important ceremonial, residential, and strategic location. The various functions it served clearly demonstrate its significance within the social, economic, and religious system of the Andean culture.