Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Haematuria Due to Radiation Cystitis Secondary to External Beam Radiotherapy for Pelvic Malignancy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Collection Questionnaire

- Severity of symptoms prior to HBO2 from a scale of 1–10?

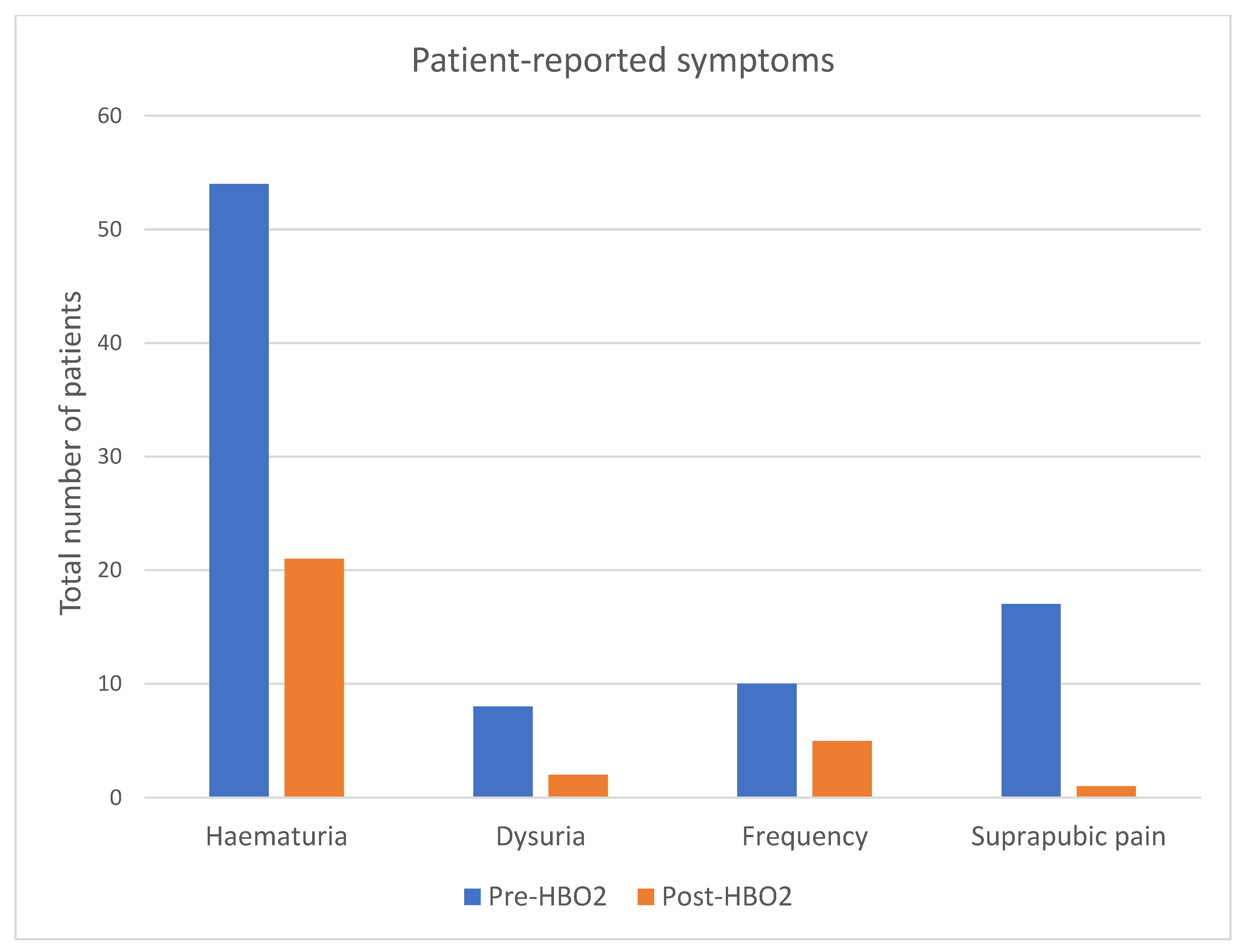

- What symptoms did you experience?

- Haematuria

- Dysuria

- Frequency

- Suprapubic pain

- How would you rate your anxiety regarding your symptoms prior to HBO2 from 1–10?

- Prior to HBO2, have you ever presented to your GP with haematuria? If so, how many times did you present?

- Prior to HBO2, have you ever presented to an ED with haematuria? If so, how many times did you present?

- Did you experience any complications from hyperbaric therapy? And if so, have they now resolved? How long did they last for?

- This is a list of possible side effects

- Middle ear barotrauma (ear pain, difficulty with ear equalisation, ruptured membrane)

- Sinus barotrauma (pressure over sinuses)

- Dental barotrauma

- Pulmonary barotrauma (bronchospasm)

- Oxygen toxicity

- Ocular side effects

- Convulsions

- On a scale of 1–10, how uncomfortable did you find receiving hyperbaric?

- Severity of symptoms after HBO2 from a scale of 1–10?

- What symptoms have you experienced?

- Haematuria

- Dysuria

- Frequency

- Suprapubic pain

- How would you rate your anxiety regarding your symptoms after your HBO2 from 1–10?

- After HBO2, have you ever presented to your GP with haematuria? If so, how many times did you present?

- After HBO2, have you ever presented to an ED with haematuria? If so, how many times did you present?

- Have you required any additional treatment?

References

- Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X. Comparison on efficacy of radical prostatectomy versus external beam radiotherapy for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 79854–79863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, C.; Duncan, C.; Lamb, B.W.; Davis, N.F.; Lynch, T.H.; Murphy, D.G.; Lawrentschuk, N. Current management of radiation cystitis: A review and practical guide to clinical management. BJU Int. 2019, 123, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-K.; Wang, Y.-J.; Li, H.-J.; Yu, Y.-F.; Huang, K.-W.; Cheng, J.C.-H. Efficacy and Safety of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Radiation-Induced Hemorrhagic Cystitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapariz-González, M.; Castro-Díaz, D.; Mejía-Rendón, D. Evaluation of the impact of the urinary symptoms on quality of life of patients with painful bladder syndrome/chronic pelvic pain and radiation cystitis: EURCIS study. Actas Urol. Esp. 2014, 38, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Browne, C.; Davis, N.F.; Mac Craith, E.; Lennon, G.M.; Mulvin, D.W.; Quinlan, D.M.; Mc Vey, G.P.; Galvin, D.J. A Narrative Review on the Pathophysiology and Management for Radiation Cystitis. Adv. Urol. 2015, 2015, 346812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helissey, C.; Cavallero, S.; Brossard, C.; Dusaud, M.; Chargari, C.; François, S. Chronic Inflammation and Radiation-Induced Cystitis: Molecular Background and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.E.; Begun, E.M.; Samir, E.; Azaiza, M.T.; Allegro, S.; Abdelhady, M. Incidence and Morbidity of Radiation-Induced Hemorrhagic Cystitis in Prostate Cancer. Urology 2019, 131, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, E.; Morillo, V.; Salvador, M.; Santafé, A.; Beato, I.; Rodríguez, M.; Ferrer, C. Hyperbaric oxygen and radiation therapy: A review. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliai, C.; Fisher, B.; Jani, A.; Wong, M.; Poli, J.; Brady, L.W.; Komarnicky, L.T. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation-induced cystitis and proctitis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 84, 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Warchol, J.M.; Cooper, J.S.; Diesing, T.S. Hyperbaric oxygen-associated seizure leading to stroke. Diving Hyperb. Med. 2017, 47, 260–262. [Google Scholar]

- Heyboer, M., 3rd; Sharma, D.; Santiago, W.; McCulloch, N. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: Side Effects Defined and Quantified. Adv. Wound Care New Rochelle 2017, 6, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeirs, L.; Tailly, T.; Ost, P.; Waterloos, M.; Decaestecker, K.; Fonteyne, V.; Van Praet, C.; Lumen, N. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation cystitis after pelvic radiotherapy: Systematic review of the recent literature. Int. J. Urol. 2020, 27, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro de Oliveira, T.M.; Carmelo Romão, A.J.; Gamito Guerreiro, F.M.; Matos Lopes, T.M. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for refractory radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Int. J. Urol. 2015, 22, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, M.A.; Osann, K.; Cho, J.; Chua, W.C.; Dash, A. Severity of hematuria effects resolution in patients treated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation-induced hematuria. Urol. Int. 2013, 91, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, T.; Nakada, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Nakashima, Y.; Banya, Y.; Fujihira, T.; Karasawa, K. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation cystitis in patients with prostate cancer: A long-term follow-up study. Urol. Int. 2012, 89, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Adamson, A.; Bahl, A.; Borwell, J.; Dodds, D.; Heath, C.; Huddart, R.; Mcmenemin, R.; Patel, P.; Peters, J.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of chemical- and radiation-induced cystitis. J. Clin. Urol. 2014, 7, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellis, A.; Papatsoris, A.; Kalentzos, V.; Deliveliotis, C.; Skolarikos, A. Hyberbaric oxygen as sole treatment for severe radiation-induced haemorrhagic cystitis. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2017, 43, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degener, S.; Pohle, A.; Strelow, H.; Mathers, M.J.; Zumbé, J.; Roth, S.; Brandt, A.S. Long-term experience of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for refractory radio- or chemotherapy-induced haemorrhagic cystitis. BMC Urol. 2015, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar, D.G.; Fadrique, G.G.; Martín, I.J.; Aguado, J.M.; Perelló, C.G.; Argente, V.G.; Sanz, M.B.; Gómez, J.G. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the management of hemorrhagic radio-induced cystitis. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2011, 64, 869–874. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz, M.; Genestal, M.; Perez, G.; Bou-Nasr, E.; Latorzeff, I.; Thoulouzan, M.; Game, X.; Soulie, M.; Beauval, J.B.; Huyghe, E. Prognostic factors of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in hemorrhagic radiation cystitis. Prog. Urol. 2017, 27, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Liu, C.S.; Chiao, C.; Lin, S.N. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in hemorrhagic radiation cystitis: A report of 20 cases. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 1994, 21, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, V.; Rice, M. The effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in radiation-induced haemorrhagic cystitis. N. Z. Med. J. 2016, 129, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mougin, J.; Souday, V.; Martin, F.; Azzouzi, A.R.; Bigot, P. Evaluation of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in the Treatment of Radiation-induced Hemorrhagic Cystitis. Urology 2016, 94, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, A.R.; Westhuyzen, J.; Dass, J.; Collins, M.K.; Webb, R.; Hewitt, S.; Fon, P.; McKay, M. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic radiation-induced tissue injuries: Australasia’s largest study. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 11, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, D.; Ferreira, C.; Catarino, R.; Correia, T.; Cardoso, A.; Reis, F.; Cerqueira, M.; Prisco, R.; Camacho, O. Hyperbaric oxygen for radiation-induced cystitis: A long-term follow-up. Actas Urol. Esp. Engl. Ed. 2020, 44, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscarsson, N.; Arnell, P.; Lodding, P.; Ricksten, S.E.; Seeman-Lodding, H. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment in radiation-induced cystitis and proctitis: A prospective cohort study on patient-perceived quality of recovery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013, 87, 670–675. [Google Scholar]

- Shilo, Y.; Efrati, S.; Simon, Z.; Sella, A.; Gez, E.; Fenig, E.; Wygoda, M.; Lindner, A.; Fishlev, G.; Stav, K.; et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for hemorrhagic radiation cystitis. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2013, 15, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Lu, G.L.; Shen, Z.J. Comparison of intravesical hyaluronic acid instillation and hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. BJU Int. 2012, 109, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parra, C.; Gómez, R.; Marchetti, P.; Rubio, G.; Felmer, A.; Castillo, O.A. Management of hemorrhagic radiation cystitis with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Actas Urol. Esp. 2011, 35, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad Al-Ali, B.; Trummer, H.; Shamloul, R.; Zigeuner, R.; Pummer, K. Is treatment of hemorrhagic radiation cystitis with hyperbaric oxygen effective? Urol. Int. 2010, 84, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Kawashima, A.; Ujike, T.; Uemura, M.; Nishimura, K.; Miyoshi, S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Int. J. Urol. 2008, 15, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safra, T.; Gutman, G.; Fishlev, G.; Soyfer, V.; Gall, N.; Lessing, J.B.; Almog, R.; Matcievsky, D.; Grisaru, D. Improved quality of life with hyperbaric oxygen therapy in patients with persistent pelvic radiation-induced toxicity. Clin. Oncol. R Coll Radiol 2008, 20, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Underwent HBO2 (n = 54) | |

|---|---|

| Median age (years, IQR) | 74 (69–78) |

| Male sex (n, %) | 52 (96) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Prostate cancer | 96% (52) |

| Cervical cancer | 2% (1) |

| Endometrial cancer | 2% (1) |

| Time between completing radiotherapy and commencing HBO2 (years, IQR) | 7 (4–10) |

| Time between completing HBO2 and completing the questionnaire (days, IQR) | 571 (357–966) |

| Median HBO2 sessions (IQR) | 40 (38–40) |

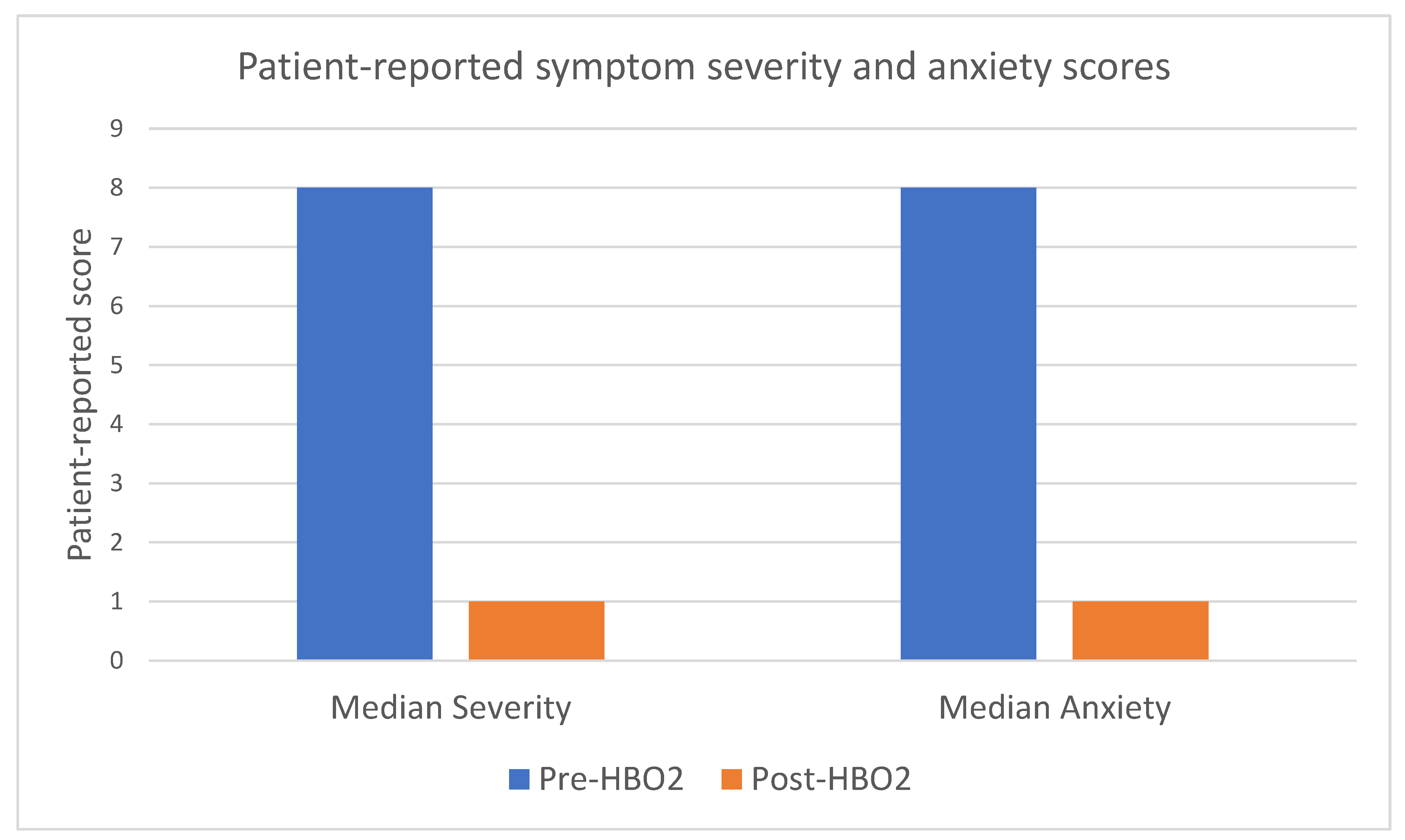

| Pre-HBO2 | |

| Symptom severity score (IQR) | 8 (7–10) |

| Anxiety score (IQR) | 8 (7–10) |

| GP visits (IQR) | 2 (0–4) |

| ED visits (IQR) | 2 (1–5) |

| Total blood transfusions | 35 |

| Post-HBO2 | |

| Symptom severity score (IQR) | 1 (0–2) |

| Anxiety score (IQR) | 1 (0–2) |

| GP visits (IQR) | 0 (0–15) |

| ED visits (IQR) | 0 (0–10) |

| Total blood transfusions | 17 |

| Complications from HBO2 | |

| Headache (n, %) | 2 (4) |

| Change in hearing (n, %) | 8 (15) |

| Change in vision (n, %) | 7 (13) |

| Complete response to HBO2 (n, %) | 33 (61) |

| Additional treatment required after HBO2 | |

| Further HBO2 (n, %) | 5 (9) |

| Fulguration (n, %) | 2 (4) |

| Bladder formalinisation (n, %) | 3 (6) |

| Prostatic artery embolization (n, %) | 2 (4) |

| Urinary diversion (n, %) | 5 (9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Société Internationale d’Urologie. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milton, T.; Noll, D.; Stapleton, P.; Shaw, H.; Hewitt, J.; Kha, M.; Pudney, T.; Le, H.; Winsor, A.; Singh-Rai, R. Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Haematuria Due to Radiation Cystitis Secondary to External Beam Radiotherapy for Pelvic Malignancy. Soc. Int. Urol. J. 2025, 6, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6050066

Milton T, Noll D, Stapleton P, Shaw H, Hewitt J, Kha M, Pudney T, Le H, Winsor A, Singh-Rai R. Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Haematuria Due to Radiation Cystitis Secondary to External Beam Radiotherapy for Pelvic Malignancy. Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal. 2025; 6(5):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6050066

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilton, Thomas, Darcy Noll, Peter Stapleton, Henry Shaw, Joseph Hewitt, Marcus Kha, Troy Pudney, Hien Le, Adrian Winsor, and Rajinder Singh-Rai. 2025. "Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Haematuria Due to Radiation Cystitis Secondary to External Beam Radiotherapy for Pelvic Malignancy" Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal 6, no. 5: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6050066

APA StyleMilton, T., Noll, D., Stapleton, P., Shaw, H., Hewitt, J., Kha, M., Pudney, T., Le, H., Winsor, A., & Singh-Rai, R. (2025). Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Haematuria Due to Radiation Cystitis Secondary to External Beam Radiotherapy for Pelvic Malignancy. Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal, 6(5), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6050066