Extended vs. Standard Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Bladder Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Evidence Acquisition

- Overall survival defined as the time from radical cystectomy to death by any cause.

- Major complications defined as any grade ≥3 Clavien–Dindo complications within 90 days of surgery.

- Disease-free survival defined as the time from radical cystectomy to disease recurrence, as determined by the investigator through clinical radiological and/or pathological information.

- Cancer-specific survival defined as the time from radical cystectomy to death caused by bladder cancer, as determined by the investigator.

- Lymphoceles requiring intervention, defined as lymphoceles requiring drainage using any method, including percutaneous or surgical (Clavien grade ≥ 3).

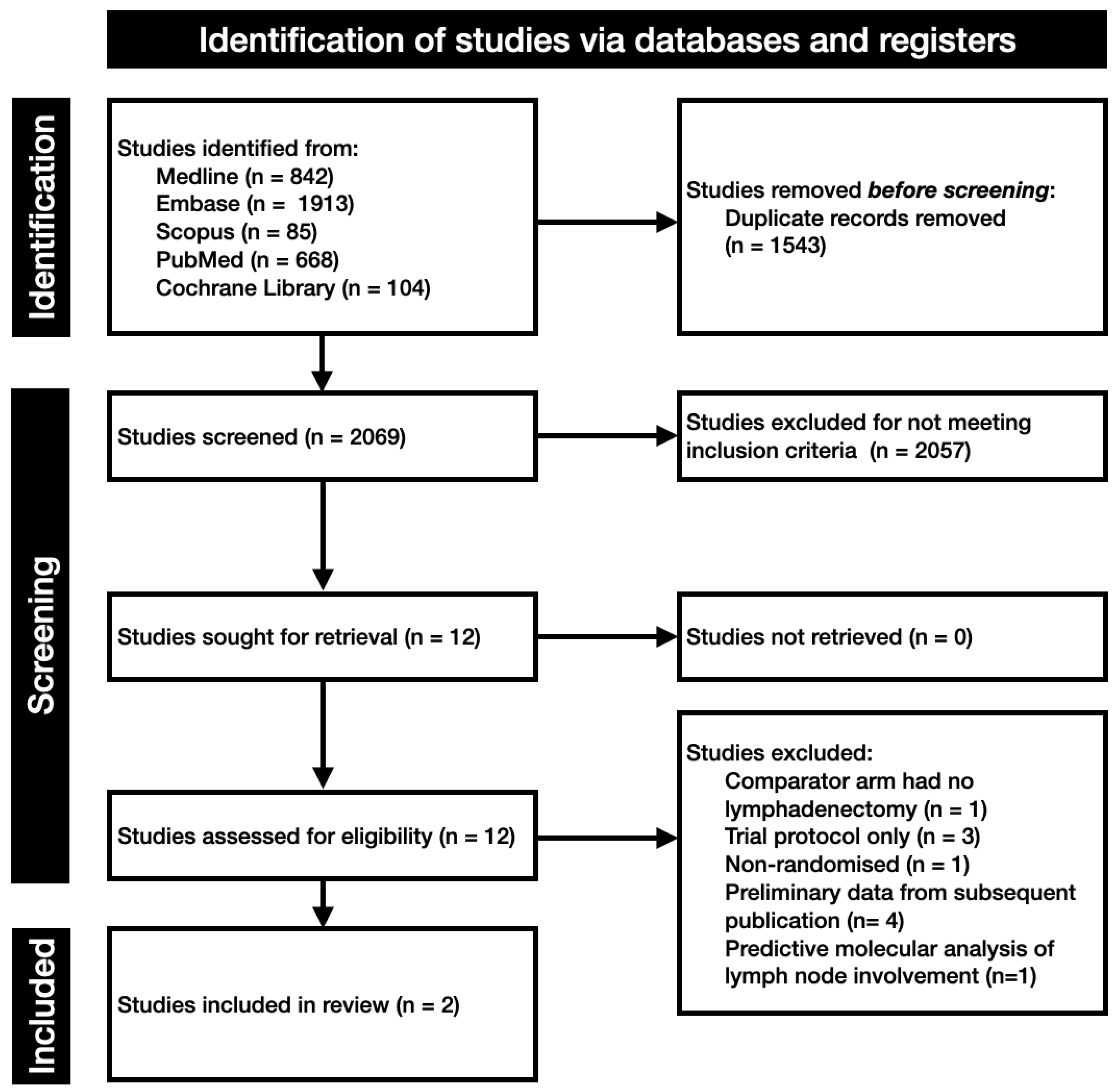

2.1. Search and Study Selection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Risk of Bias

3. Evidence Synthesis

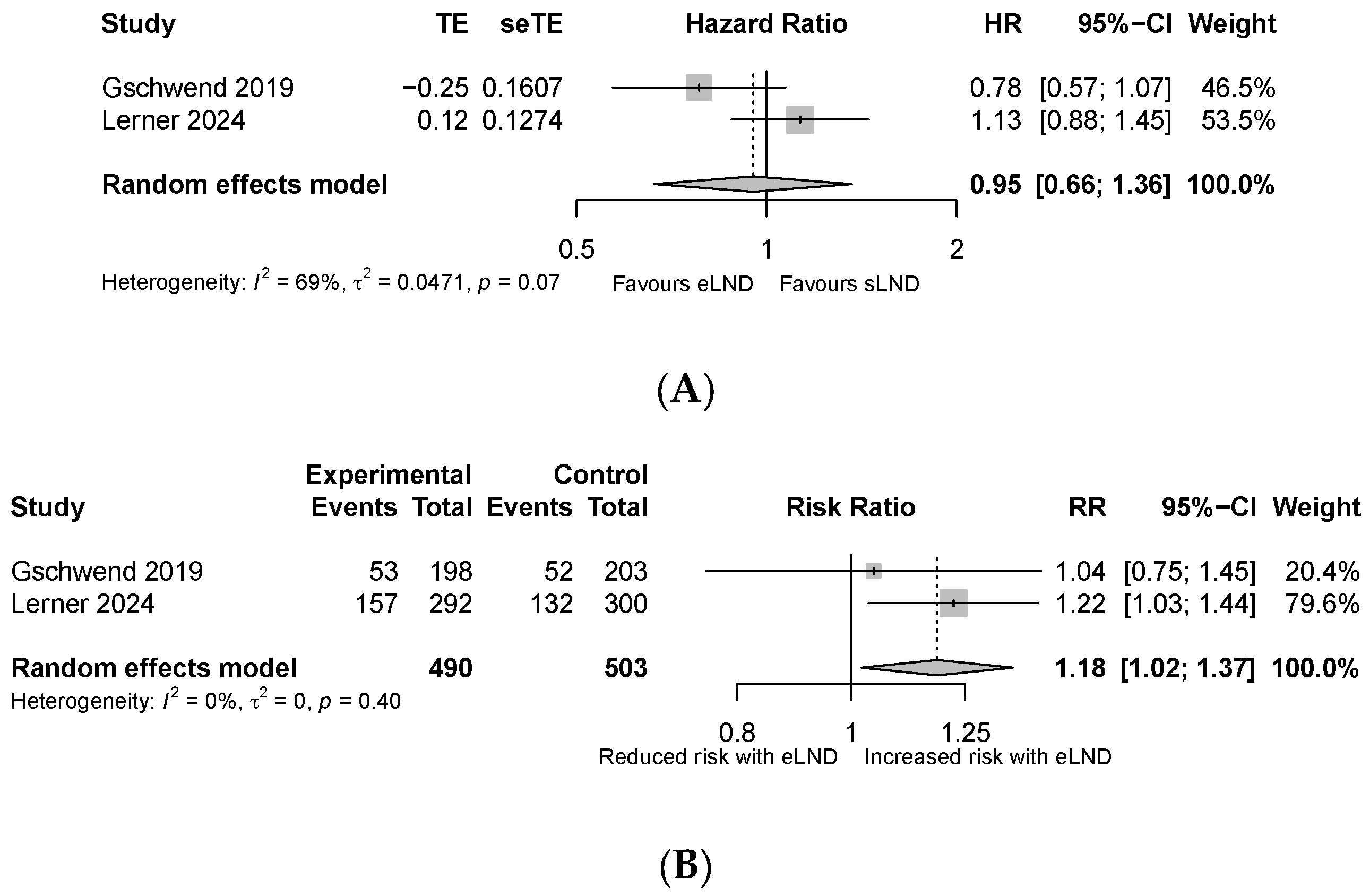

3.1. Primary Outcomes

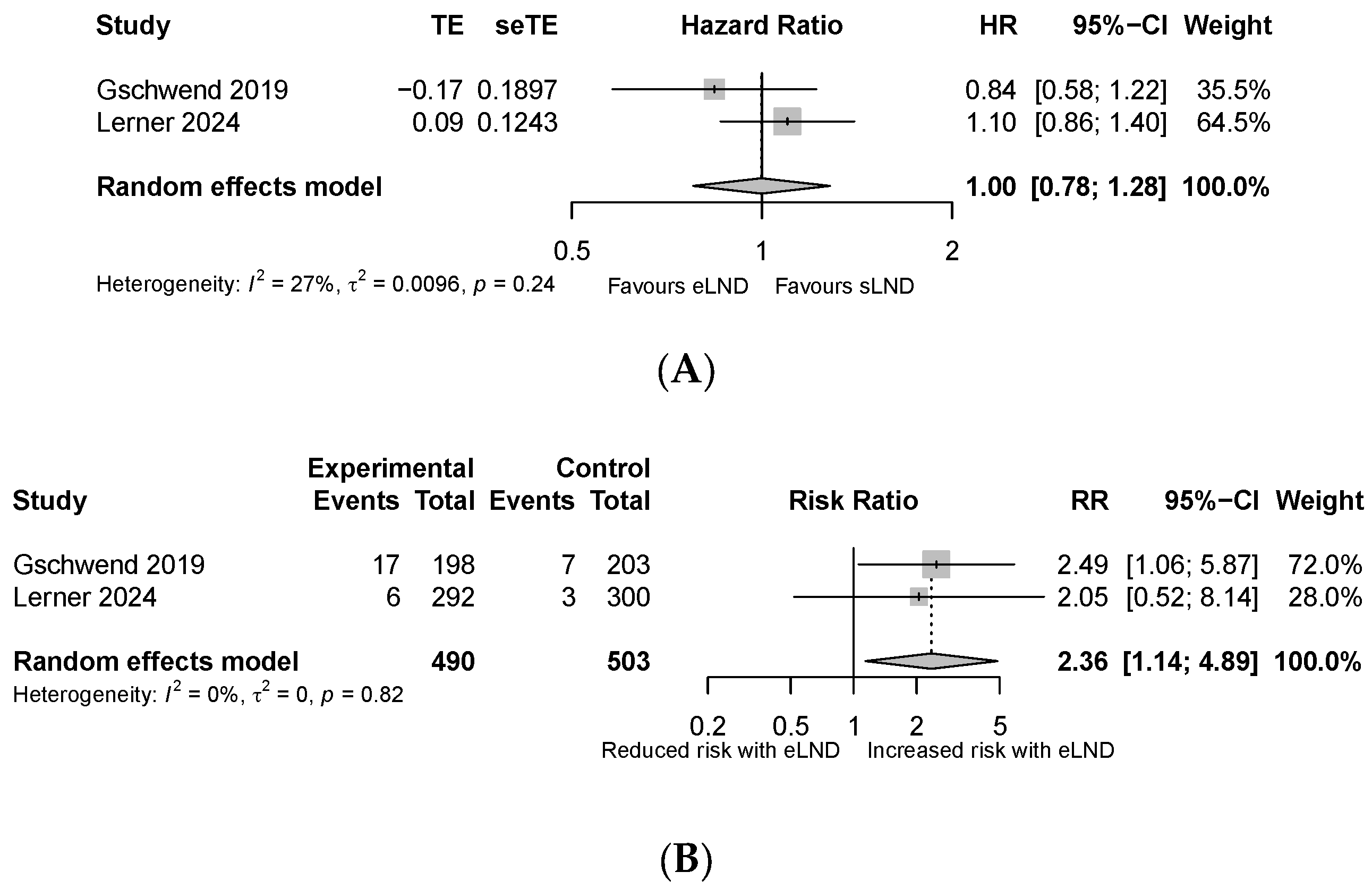

3.2. Secondary Outcomes

3.3. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Witjes, J.A.; Bruins, H.M.; Carrión, A.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Fietkau, R.; Gakis, G.; Lorch, A.; Martini, A.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2023 Guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2024, 85, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, K.L.; Ristau, B.T.; Yamase, H.T.; Taylor, J.A., III. Prognostic implications of lymph node involvement in bladder cancer: Are we understaging using current methods? BJU Int. 2011, 108, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonati, C.; Mordasini, L.; Afferi, L.; De Cobelli, O.; Di Trapani, E.; Necchi, A.; Briganti, A.; Montorsi, F.; Simeone, C.; Zamboni, S.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative lymph node staging of bladder cancer according to different lymph node locations: A multicenter cohort from the European Association of Urology—Young Academic Urologists. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 40, 195.e27–195.e35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Larcher, A.; Sun, M.; Schiffmann, J.; Tian, Z.; Shariat, S.; McCormack, M.; Saad, F.; Fossati, N.; Abdollah, F.; Briganti, A.; et al. Differential effect on survival of pelvic lymph node dissection at radical cystectomy for muscle invasive bladder cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollah, F.; Sun, M.; Schmitges, J.; Djahangirian, O.; Tian, Z.; Jeldres, C.; Perrotte, P.; Shariat, S.F.; Montorsi, F.; Karakiewicz, P.I. Stage-specific impact of pelvic lymph node dissection on survival in patients with non-metastatic bladder cancer treated with radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2012, 109, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruins, H.M.; Veskimae, E.; Hernandez, V.; Imamura, M.; Neuberger, M.M.; Dahm, P.; Stewart, F.; Lam, T.B.; N’dow, J.; van der Heijden, A.G.; et al. The Impact of the Extent of Lymphadenectomy on Oncologic Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy for Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2014, 66, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Littlewood, A.; Marshall, C.; Metzendorf, M.I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Rader, T.; Shokraneh, F.; Thomas, J.; et al. Searching for and selecting studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 67–107. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 241–284. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gschwend, J.E.; Heck, M.M.; Lehmann, J.; Rübben, H.; Albers, P.; Wolff, J.M.; Frohneberg, D.; de Geeter, P.; Heidenreich, A.; Kälble, T.; et al. Extended Versus Limited Lymph Node Dissection in Bladder Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: Survival Results from a Prospective, Randomized Trial. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, S.P.; Tangen, C.; Svatek, R.S.; Daneshmand, S.; Pohar, K.S.; Skinner, E.; Schuckman, A.; Sagalowsky, A.I.; Smith, N.D.; Kamat, A.M.; et al. Standard or Extended Lymphadenectomy for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, P.; Tilki, D.; Eslick, G.D. Extent of lymph node dissection and recurrence-free survival after radical cystectomy: A meta-analysis. Urol. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simone, G.; Papalia, R.; Ferriero, M.; Guaglianone, S.; Castelli, E.; Collura, D.; Muto, G.; Gallucci, M. Stage-specific impact of extended versus standard pelvic lymph node dissection in radical cystectomy. Int. J. Urol. 2013, 20, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hwang, E.C.; Sathianathen, N.J.; Imamura, M.; Kuntz, G.M.; Risk, M.C.; Dahm, P. Extended versus standard lymph node dissection for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder in patients undergoing radical cystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 5, Cd013336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abol-Enein, H.; Tilki, D.; Mosbah, A.; El-Baz, M.; Shokeir, A.; Nabeeh, A.; Ghoneim, M.A. Does the extent of lymphadenectomy in radical cystectomy for bladder cancer influence disease-free survival? A prospective single-center study. Eur. Urol. 2011, 60, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dharaskar, A.; Kumar, V.; Kapoor, R.; Jain, M.; Mandhani, A. Does extended lymph node dissection affect the lymph node density and survival after radical cystectomy? Indian J. Cancer 2011, 48, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Briganti, A.; Chun, F.K.-H.; Salonia, A.; Suardi, N.; Gallina, A.; Da Pozzo, L.F.; Roscigno, M.; Zanni, G.; Valiquette, L.; Rigatti, P.; et al. Complications and other surgical outcomes associated with extended pelvic lymphadenectomy in men with localized prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2006, 50, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Lichtbroun, B.; Sterling, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Singer, E.A.; Jang, T.L.; Ghodoussipour, S.; Kim, I.Y. Comparison of perioperative complications for extended vs standard pelvic lymph node dissection in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2022, 10, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Yan, P.; Kang, H.; Shu, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, X. A preliminary investigation of precise visualization, localization, and resection of pelvic lymph nodes in bladder cancer by using indocyanine green fluorescence-guided approach through intracutaneous dye injection into the lower limbs and perineum. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1384268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, A.; Rouanne, M.; Taconet, S.; Radulescu, C.; Neuzillet, Y.; Girma, A.; Beaufrere, A.; Lebret, T.; Le Stanc, E.; Grellier, J.-F. Integrated analysis of (18)F-FDG PET/CT improves preoperative lymph node staging for patients with invasive bladder cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 4286–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, G.S.; Finelli, A.; Lockwood, G.; Saravanan, A.; Evans, A.; Jewett, M.A.; Trachtenberg, J.; Robinette, M.; Fleshner, N.E. Effect of Healthcare Provider Characteristics on Nodal Yield at Radical Cystectomy. Urology 2008, 72, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | LEA [10] | SWOG [11] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2019 | 2024 | ||

| Dissection method | sLND | eLND | sLND | eLND |

| Sample size | 203 | 198 | 300 | 292 |

| Number of nodes taken | 19 (12–26) | 31 (22–47) | 24 (6–61) | 39 (15–94) |

| FU (months) | 58.4 | 58.4 | 73.2 | 73.2 |

| Age (yr) | 68 (61–73) | 67 (59–74) | 68 (38–90) | 69 (37–92) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | Excluded | Excluded | 170 (57) | 166 (57) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 30 (15) | 28 (14) | 33 (11) | 32 (11) |

| T-stage | ||||

| pT1 | 24 (12) | 31 (16) | NA | NA |

| pT2 | 81 (40) | 88 (44) | 213 (71) | 208 (71) |

| pT3 | 68 (34) | 63 (32) | 87 (29) | 84 (29) |

| pT4 | 30 (15) | 16 (8.1) | ||

| N-stage | ||||

| pNx | 0 | 2 (1) | NA | NA |

| pN0 | 147 (72) | 152 (77) | 229 (76) | 217 (74) |

| pN+ | 56 (28) | 44 (22) | NA | NA |

| pN1 | 15 (7.4) | 14 (7.1) | 36 (12) | 34 (12) |

| pN2 | 41 (20) | 29 (15) | 31 (10) | 20 (7) |

| pN3 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1) | 21 (7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Société Internationale d’Urologie. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santucci, J.; Stapleton, P.; Perera, M.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Murphy, D.; Sathianathen, N. Extended vs. Standard Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Bladder Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Soc. Int. Urol. J. 2025, 6, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6030037

Santucci J, Stapleton P, Perera M, Lawrentschuk N, Murphy D, Sathianathen N. Extended vs. Standard Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Bladder Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal. 2025; 6(3):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6030037

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantucci, Jordan, Peter Stapleton, Marlon Perera, Nathan Lawrentschuk, Declan Murphy, and Niranjan Sathianathen. 2025. "Extended vs. Standard Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Bladder Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal 6, no. 3: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6030037

APA StyleSantucci, J., Stapleton, P., Perera, M., Lawrentschuk, N., Murphy, D., & Sathianathen, N. (2025). Extended vs. Standard Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Bladder Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Cystectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal, 6(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj6030037