Abstract

Objectives: We aimed to evaluate management strategies for female urinary incontinence, specifically stress urinary incontinence (SUI), and anterior vaginal prolapse (pelvic organ prolapse, POP), emphasizing diagnostic methods, treatment options, and factors influencing surgical outcomes. Methods: We conducted a thorough literature review examining diagnostic tools, including physical examinations, urodynamic testing, and pessary evaluations, alongside treatment options for SUI and POP. Both surgical interventions, such as mid-urethral sling placement and anterior colporrhaphy, and non-surgical methods, including pelvic floor exercises, were analyzed. This review assesses these approaches’ efficacy, complications, and outcomes, incorporating current clinical guidelines and evidence-based practices. Results: Evidence indicates that SUI frequently coexists with POP, with a notable proportion of cases being occult until a prolapse is reduced. Diagnostic methods such as pessary testing and urodynamic evaluations are essential in identifying masked SUI, though their predictive accuracy varies. Surgical techniques such as using mid-urethral slings are highly effective but pose risks, including voiding dysfunction and lower urinary tract injury. Long-term data emphasize the need for personalized treatment strategies, with combined procedures showing superior outcomes for the concurrent management of POP and SUI in select cases. Conclusions: Effective management of SUI and POP requires a personalized approach, factoring in the severity of a prolapse and the likelihood of postoperative incontinence. While conservative treatments are practical initial options, surgical solutions, such as mid-urethral slings and apical suspension procedures, offer robust, lasting results for advanced cases. Preoperative diagnostics, collaborative decision-making, and tailored treatment plans are essential to optimize success and minimize complications. Future research should prioritize enhancing diagnostic precision and refining surgical methods to further advance patient care.

1. Introduction

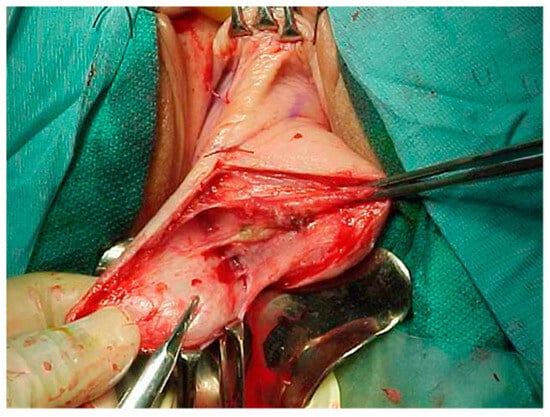

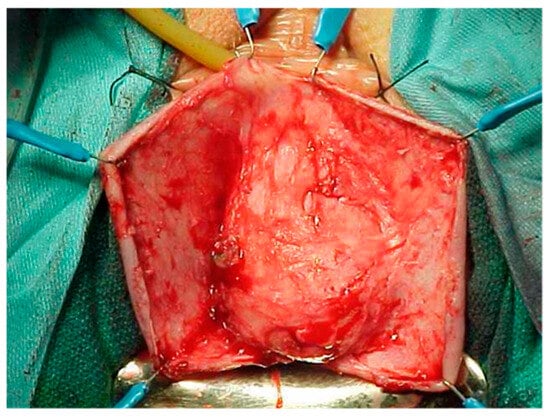

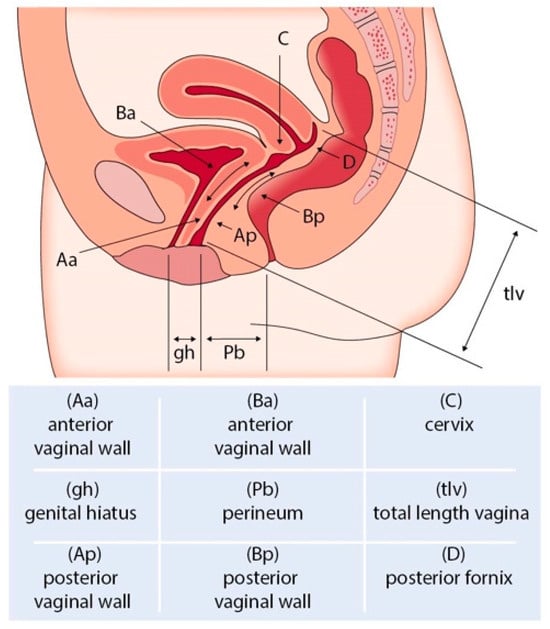

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is defined as the descent of one or more of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina outside their usual anatomical location [1]. POP occurs in about 40% of females worldwide [2]. A cystocele is a specific type of POP known as an anterior vaginal wall prolapse [3]. This pelvic floor defect occurs when the supportive tissues around the bladder and vaginal wall, which serve to support the vaginal wall and hold the bladder in its normal anatomical position, weaken and stretch, allowing the bladder and vaginal wall to fall into the vaginal canal as shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, which illustrate images and the dissection of a high-grade cystocele after retropubic sling placement. Often, this pelvic floor defect of the anterior compartment involves inadequate urethral closure. This impairment in urethral closure and associated anatomical changes in urethral function may lead to stress urinary incontinence [4]. Concomitant pelvic organ prolapse, and stress urinary incontinence represent a significant diagnostic, clinical, and surgical dilemma for pelvic-floor surgeons.

Figure 1.

Pelvic examination of high-grade pelvic organ prolapse (stage IV).

Figure 2.

MRI—T2 weighted image of high-grade anterior compartment prolapse.

Figure 3.

Dissection of high-grade cystocele after retropubic sling placement.

Figure 4.

Dissection of high-grade cystocele after retropubic sling placement.

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is involuntary urinary leakage due to increased abdominal pressure, which can be caused by activities such as sneezing, coughing, exercise, lifting, and positional changes. It is estimated that one-third of adult women are affected by this condition, confirming its very high prevalence [5].

Though the utility of urethral function assessments remains controversial, some clinicians utilize leak point pressure, and others use urethral closure pressure, to assess stress urinary incontinence. Intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) is often defined as a leak point pressure of less than 60 cm of H2O or a maximal urethral closure pressure of less than 20 cm of H2O, even in the presence of minimal urethral mobility [6]. Many pelvic floor surgeons also utilize Valsalva leak point pressure for objective measurements to assess urethral closure integrity. These objective measurements can be obtained during urodynamic testing, particularly with video urodynamics. However, in most cases, urodynamic testing is not necessary for the diagnosis of stress urinary incontinence, though objective observation of stress urinary continence is imperative.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is reported to affect up to 50% of parous women, and of these, 62% will have undergone surgical correction for this problem by the age of 80 [7]. Nonetheless, there is wide variation in the reported POP prevalence rates. When POP is defined and graded by symptoms, the prevalence is reported to be 3–6%, while it is 41–50% when based on physical examination [7]. In pelvic examinations, the anterior compartment is the most frequently reported site of prolapse, and it is detected twice as often as posterior compartmental defects and three times more commonly than apical prolapses [7].

The rate at which surgical operations for pelvic organ prolapse are performed varies greatly. In the USA, the rate is 2.6 per 1000 women, while it is 0.5 per 1000 women in Switzerland [7]. There is also significant variation in clinical judgment among surgeons when managing pelvic organ prolapse. Some clinicians are more surgically inclined, while others prefer adjuvant techniques, including mesh repair. Some surgeons opt for multiple concurrent procedures, such as mid-urethral sling placement, when occult stress urinary incontinence is suspected.

Such large variations in the rate and types of surgery performed for pelvic organ prolapse may be explained by a variety of factors, including women’s preferences, cultural and demographic variables, access to healthcare professionals, surgeons’ training, and the lack of a clear consensus regarding guidelines for the surgical management of prolapses associated with occult stress urinary incontinence [7]. Given the increasing demand for POP surgery, it is crucial that we perform effective, durable, and cost-efficient interventions with minimal morbidity. Clinical judgment is of paramount importance in such scenarios.

Historically, anterior colporrhaphy (AC) was the standard procedure for managing anterior compartment prolapse. However, it carries a high recurrence rate, as estimated by the Italian guidelines and the German-speaking group—which includes Austria, Germany, and Switzerland—an estimation that is based on a literature review that evaluates various surgical decision-making algorithms and compares national and international recommendations and guidelines for pelvic organ prolapse surgery using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II-S (AGREE II-S) comparison method [8].

The importance of paravaginal defects in anterior compartment prolapse has been recognized. Since then, several vaginal, abdominal, and laparoscopic procedures have been described [9]. However, no randomized controlled studies have evaluated these in isolation. Raz et al. (1996) popularized the needle suspension procedure for cystocele repair and reported success rates in case series ranging from 90 to 98% [10,11]. Further studies demonstrated reduced recurrence and reoperation rates when apical suspension procedures were performed [12,13,14].

However, this message does not always seem to be reflected in clinical practice. The rates of apical or posterior compartment prolapse are significantly higher following polypropylene mesh placement, with a mesh exposure rate of 10.4% and 6.3% requiring surgical correction [7]. Conflicting data exist regarding the advantages of polypropylene mesh compared to anterior colporrhaphy, with relatively high mesh complication rates reported in the long term. In the literature review performed by Seifalian et al., chronic pain, infection, and mesh exposure were reported as significant complications of mesh use due to their mechanical and physicochemical properties, which, in the long term, may cause erosion due to a significant mismatch between its lack of integration and the viscoelastic properties of the surrounding tissue [15].

It is well-known that POP and SUI often coexist, particularly in advanced stages of POP. The prevalence of these conditions occurring together varies depending on the severity of the prolapse and other risk factors, such as obesity, pelvic floor tissue integrity, and having undergone prior pelvic floor surgical interventions [16]. When using the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system (POP-Q), an objective, site-specific system for describing, quantifying, and staging pelvic support in women [17], it was demonstrated that over 50% of patients with stage IV (Figure 1 and Figure 2) POP-Q (leading edge ≥ +(TVL-2) cm) (Figure 5) pelvic organ prolapse also had SUI as assessed via urodynamic testing [6]. Of the patients diagnosed with SUI, 40% were asymptomatic [18].

Figure 5.

POP Q staging of pelvic organ prolapse.

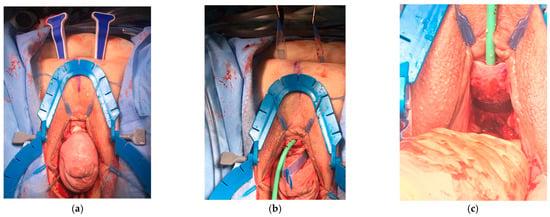

In the treatment of females with both POP and SUI, options include conservative treatments like lifestyle changes, such as weight loss; routine pelvic floor exercises (Kegel exercises); and obstetric care strategies, such as reducing pushing time during labor [19]. Surgical approaches may include procedures such as the placement of a mid-urethral sling (retropubic or transobturator) (Figure 6a–c), autologous fascia pubovaginal sling placement, or Burch colposuspension based on the AUA SUI guidelines from 2023 [6]. Before considering surgical intervention for patients with concurrent stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse, thorough history-taking, a detailed physical and pelvic examination, a limited neurologic examination, a post-void residual volume assessment, and a urinalysis should be performed. Based on the 2023 AUA SUI guidelines [6], additional evaluation is warranted for patients with high-grade pelvic organ prolapse (POP-Q stage 3 or higher) if SUI is not observed upon prolapse reduction.

Figure 6.

The surgical placement of a Lynx Suprapubic Mid-Urethral Sling to treat stress incontinence. (a) A complete anterior compartment prolapse with the sling delivery device placed suprapubically. (b,c) Placement and tightening of the mid-urethral sling.

Patients with POP often present with bladder symptoms such as urinary incontinence or voiding difficulties. Many women with advanced POP do not experience SUI. However, when the prolapse is reduced with a pessary, sponge holder, or speculum, SUI may be observed in 10–80% of cases [20,21,22,23]. This type of SUI, which becomes evident only when the prolapse is reduced, is termed occult, masked, or latent SUI. Although different techniques for prolapse reduction have been described, a gold standard has not been established [24,25]. Women with preoperatively negative tests for occult SUI have a low risk of developing SUI postoperatively [24,26].

Despite the lack of a consensus, there are several recommendations for careful surgeons. Continent women who test negative for occult stress urinary incontinence do not require concurrent prophylactic anti-incontinence procedures. Anterior mesh repair increases the risk of stress urinary incontinence compared to anterior repair without a mesh for continent patients. Continent women with occult stress urinary incontinence benefit more from pelvic organ prolapse repair with concomitant anti-incontinence procedures compared to pelvic organ prolapse surgery without such procedures. For women with pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence, concomitant continence procedures increase the likelihood of curing postoperative stress urinary incontinence.

2. Discussion

The management of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) for patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) presents a unique challenge due to the occult nature of SUI in this population. Various factors, such as older age (>50 years), positive pessary tests, previous pelvic surgery, obesity, menopause, moderate or severe urethral obstruction/compression, and diabetes, have been identified as increasing the risk of de novo SUI after POP surgery [27].

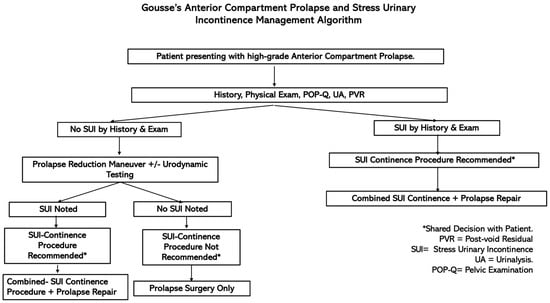

According to the AUA guidelines for SUI, clinicians should perform additional evaluations for patients being considered for surgical intervention, especially when dealing with high-grade pelvic organ prolapse (POP-Q stage 3 or higher) if SUI is not evident following prolapse reduction (Figure 7) [6]. Various manual reduction methods, including tampon use, pessary tests, the use of ring forceps, and split speculum use, are employed to test for occult SUI [24]. Among these, the pessary test is less likely to induce leakage prior to surgery, whereas the swab prolapse test has the highest positive predictive value [24].

Figure 7.

Decision-making flowchart for women undergoing prolapse surgery with or without SUI.

Reena et al. emphasized the importance of conducting preoperative testing to detect occult SUI in patients with POP [20]. In their study, 67.9% of women tested positive for occult SUI preoperatively, and 43.6% developed SUI postoperatively [20]. They noted that preoperative testing using the Pyridium pad test and pessary insertion demonstrated high sensitivity (64.2%) and specificity (100%), providing a valuable tool that can help clinicians decide whether to include a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure during surgery [20].

Song et al. further expanded on the importance of predictive tests, highlighting the use of the preoperative 1 h pad test with pessary insertion to predict the need for a mid-urethral sling (MUS) following prolapse surgery [28]. Their study demonstrated that a pad weight cutoff of 1.9 g had a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 83.9% [28]. This provides clinicians with a more reliable method for predicting postoperative SUI and deciding whether concurrent MUS placement should be performed [28]. Sierra et al. emphasized the reliability of preoperative urodynamics, which demonstrated a 97.9% negative predictive value for postoperative SUI [29]. They noted the effectiveness of urodynamics as a negative predictive tool, which can help avoid unnecessary concomitant surgery [29]. However, the utility of urodynamic testing may be limited in the diagnosis of occult SUI. While it can objectively evaluate lower urinary tract dysfunction with voiding phase etiologies, it can not independently diagnose SUI and must be complemented by a thorough clinical evaluation and patient history. Additionally, its invasive nature, discomfort, and risks of urinary tract infections limit its routine application [30].

For patients with POP, additional measurements, such as maximal urethral closure pressure (MUCP), may provide further guidance for surgical decision-making [31]. Patients with an MUCP of less than 50 cm H2O are more likely to benefit from concomitant SUI surgery, as this value indicates weakened urethral function [31].

Another study demonstrated the use of a de novo SUI prediction model, which has been shown to have higher accuracy compared to traditional stress tests [32]. While this model has been validated in external studies and found to be useful in shared decision-making with patients [33], some studies have reported less accuracy in different patient populations [34], highlighting the need for individualized assessments. According to the AUA guidelines for SUI, if these preoperative tests are negative, it is generally recommended to proceed with POP surgery without an anti-incontinence procedure [6]. However, if the tests are positive, concurrent (single stage) surgery to address both POP and SUI is often recommended [6]. Staged procedures are typically undesirable due to the need for additional anesthesia, time away from work, family, and recuperation [7].

The price a POP patient may pay for undergoing an unnecessary anti-incontinence procedure is significant. A thorough preoperative evaluation allows patients to undergo a single operation that addresses all clinical issues. Moreover, unnecessary anti-incontinence surgery carries potential risks, including complications such as bleeding, urethral and bladder injury, and postoperative voiding dysfunction [7]. Adequate patient counseling and shared decisions are warranted in these cases.

One shared decision-making model proposed by Tayrac et al. was designed for women planning surgery for repairing stage II or higher pelvic organ prolapse (Figure 2) [7]. In this model, patients are assessed for urinary symptoms via a pelvic examination, urinary stress testing, assessment for a history of SUI, and a discussion of patient goals and quality of life [7]. If symptomatic SUI is present preoperatively, a concomitant continence procedure is recommended [7]. If SUI is not present, the patient can proceed with an abdominal sacrocolpopexy and concomitant Burch procedure or undergo vaginal surgery [7]. After vaginal surgery, the patient is then reassessed for occult SUI postoperatively, and if occult SUI is present, a continence procedure should be discussed with the patient, and a recommendation for the procedure should be given [7]. However, if no occult SUI is present, a continence procedure should not be recommended, and the patient’s wishes should be discussed [7]. Despite this approach, some patients may still exhibit occult SUI after multiple preoperative reduction trials, raising questions about optimal management strategies for these individuals.

Synthetic midurethral sling (SMUS) surgery remains the leading surgical option for treating SUI due to its safety and effectiveness, though these slings are not without risks [35]. Intraoperative complications, while infrequent, can include bleeding, which occurs in less than 1% of cases, and perforations of the bladder or urethra, which are particularly common during retropubic sling procedures (5%) and have a lower incidence in transobturator sling procedures (<1%) [35,36]. The transobturator approach, as highlighted in a meta-analysis, tends to have fewer associated complications overall [35,37]. Autologous fascial sling (AFS) placement is also an available surgical option for treating SUI. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCT) that included studies published before September 2023, Grigoryan et al. assessed the efficacy of autologous slings such as AFSs in comparison to SMUSs. Interestingly, they did not find any statistically significant differences in the cure rate, frequency of urinary retention, or need for self-catheterization between the two methods. As a result, autologous fascial slings (AFSs) were found to be equally effective as synthetic mid-urethral slings (SMUSs) in managing stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in women. However, AFSs demonstrated a lower incidence of long-term postoperative complications, while SMUSs were associated with shorter operation times, reduced hospital stays, and less de novo urgency [38]. Erosion into the urethra is quite rare (<1%), and in many cases, it results from an unrecognized bladder or urethral perforation during the procedure rather than true erosion [35].

Another commonly used technique is the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure, which has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing postoperative SUI [39]. In a study by Groutz et al., the TVT procedure resulted in minimal complications, with only 2% of women experiencing symptomatic SUI postoperatively, though the long-term durability of the procedure remains under investigation [39]. Recent studies show that extrusion rates for slings vary between 1.1% for the TVT-O and 2.6% for the traditional TVT [35,40]. Routine intraoperative cystourethroscopy is essential to minimize urinary tract injuries, and smaller bladder injuries typically resolve with conservative management, such as catheter drainage for 24–48 h. However, if a urethral injury occurs, the use of synthetic mesh is contraindicated, and an autologous pubovaginal sling should be considered instead.

To assess additional approaches, Fuco F et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis looking at Burch colposuspension, pubovaginal slings, and midurethral retropubic and transobturator tape (RT and TOT, respectively) since they are the most popular surgical treatments for SUI. Interestingly, they found that patients treated with retropubic slings (RT) achieved slightly better continence rates compared to those who underwent Burch colposuspension but faced a significantly increased risk of intraoperative complications. When compared with pubovaginal slings, RT demonstrated similar effectiveness, though pubovaginal slings were more commonly associated with storage lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Additionally, while RT showed marginally higher objective cure rates than transobturator tape (TOT), the subjective cure rates were comparable between the two. TOT, however, was associated with a lower likelihood of bladder and vaginal perforations as well as fewer cases of storage LUTS compared to RT [41].

It is also paramount to highlight other contemporary methods that are being used to treat patients with pelvic organ prolapse. For instance, robotically assisted sacrocolpopexy has become a popular minimally invasive approach that may reduce the length of stay in the hospital and recovery time for patients. Sacrocolpopexy is the “gold standard” repair therapy for apical prolapse for those who desire to maintain their sexual function, and minimally invasive approaches offer similar efficacy to and fewer risks than open techniques while also reducing hospital length of stay (LOS) and recovery time for patients [42].

Postoperatively, lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), voiding dysfunction, and urinary retention are key concerns that arise early after surgery [35]. Although the overall incidence of these complications is relatively low, ranging between 1% and 2%, they can require further intervention in cases of obstructive symptoms like urinary retention or incomplete bladder emptying [35]. As with all surgeries, individualized patient assessments and careful surgical planning are key to balancing treatment efficacy and risk.

3. Conclusions

Managing stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) requires thorough preoperative evaluation due to the risk of occult SUI. Key tests, like pessary and urodynamic assessments, help identify those who may need concurrent SUI surgery. While combining surgeries can reduce postoperative SUI, a two-stage approach may be preferable to avoid overtreatment. Individualized treatment plans are essential to balance these risks and benefits. Most importantly, more research should be conducted on these two conditions to determine the best course of treatments for patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.M. and A.G. (Angelo Gousse); methodology, R.F.M.; software, D.A.B.; validation, R.F.M., A.G. (Angelica Gousse) and D.A.B.; formal analysis, R.F.M.; investigation, R.F.M.; resources, A.G. (Angelica Gousse) and A.G. (Angelo Gousse); data curation, D.A.B. and D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.M.; writing—review and editing, R.F.M., A.G. (Angelica Gousse), D.A.B., D.A. and A.G. (Angelo Gousse); visualization, D.A.B.; supervision, A.G. (Angelo Gousse); project administration, A.G. (Angelo Gousse); funding acquisition, A.G. (Angelo Gousse). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the FIU HWCOM administration for their unwavering support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Collins, S.; Lewicky-Gaupp, C. Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 51, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, M.; Huang, Y.; Xue, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, M. Global burden and trends of pelvic organ prolapse associated with aging women: An observational trend study from 1990 to 2019. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 975829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Laganà, A.S.; Gulino, F.A.; Tropea, A.; Tarda, S. Prosthetic surgery versus native tissue repair of cystocele: Literature review. Updat. Surg. 2016, 68, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, K. Recent Advances in Understanding Pelvic-Floor Tissue of Women With and Without Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Considerations for Physical Therapists. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygaard, I.E.; Heit, M. Stress Urinary Incontinence. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 104, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobashi, K.C.; Vasavada, S.; Bloschichak, A.; Hermanson, L.; Kaczmarek, J.; Kim, S.K.; Kirkby, E.; Malik, R. Updates to Surgical Treatment of Female Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI): AUA/SUFU Guideline (2023). J. Urol. 2023, 209, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tayrac, R.; Antosh, D.D.; Baessler, K.; Cheon, C.; Deffieux, X.; Gutman, R.; Lee, J.; Nager, C.; Schizas, A.; Sung, V.; et al. Summary: 2021 International Consultation on Incontinence Evidence-Based Surgical Pathway for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecorella, G.; Morciano, A.; Sparic, R.; Tinelli, A. Literature review, surgical decision making algorithm, and AGREE II-S comparison of national and international recommendations and guidelines in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ. Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2024, 167, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.R. An Anatomic Operation for the Cure of Cystocele. Trans. Am. Assoc. Obstet. Gynecol. Year 1912, 24, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Raz, S.; Klutke, C.G.; Golomb, J. Four-Corner Bladder and Urethral Suspension for Moderate Cystocele. J. Urol. 1989, 142, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, S.; Little, N.A.; Juma, S.; Sussman, E.M. Repair of Severe Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse (Grade IV Cystourethrocele). J. Urol. 1991, 146, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilber, K.S.; Alperin, M.; Khan, A.; Wu, N.; Pashos, C.L.; Clemens, J.Q.M.; Anger, J.T. Outcomes of Vaginal Prolapse Surgery Among Female Medicare Beneficiaries: The Role of Apical Support. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R.P.; Koduri, S.; Lobel, R.W.; Culligan, P.J.; Tomezsko, J.E.; Winkler, H.A.; Sand, P.K. Protective effect of suburethral slings on postoperative cystocele recurrence after reconstructive pelvic operation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 185, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gardy, M.; Kozminski, M.; Delancey, J.; Elkins, T.; Mcguire, E.J. Stress Incontinence and Cystoceles. J. Urol. 1991, 145, 1211–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifalian, A.; Basma, Z.; Digesu, A.; Khullar, V. Polypropylene Pelvic Mesh: What Went Wrong and What Will Be of the Future? Biomedicines 2023, 11, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nygaard, I. Prevalence of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in US Women. JAMA 2008, 300, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persu, C.; Chapple, C.R.; Cauni, V.; Gutue, S.; Geavlete, P. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q)—A new era in pelvic prolapse staging. J. Med. Life 2011, 4, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muñiz, K.S.; Pilkinton, M.; Winkler, H.A.; Shalom, D.F. Prevalence of stress urinary incontinence and intrinsic sphincter deficiency in patients with stage IV pelvic organ prolapse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, R.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Conservative interventions for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: A systematic review protocol. Medicine 2019, 98, e18116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reena, C.; Kekre, A.N.; Kekre, N. Occult stress incontinence in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2007, 97, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D.; Arunkalaivanan, A.S. Prevalence of occult stress incontinence in continent women with severe genital prolapse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 27, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haessler, A.L.; Lin, L.L.; Ho, M.H.; Betson, L.H.; Bhatia, N.N. Reevaluating occult incontinence. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 17, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellström Engh, A.M.; Ekeryd, A.; Magnusson, Å.; Olsson, I.; Otterlind, L.; Tobiasson, G. Can de novo stress incontinence after anterior wall repair be predicted?: De novo stress incontinence and anterior wall repair. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2011, 90, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visco, A.G.; Brubaker, L.; Nygaard, I.; Richter, H.E.; Cundiff, G.; Fine, P.; Zyczynski, H.; Brown, M.B.; Weber, A.M.; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: The Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int. Urogynecology J. 2008, 19, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, B.; Spettel, S.; Kurman, J.; De, E. Ambulatory Pessary Trial Unmasks Occult Stress Urinary Incontinence. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2012, 2012, 392027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauls, R.N.; Segal, J.L.; Silva, W.A.; Kleeman, S.D.; Karram, M.M. Sexual function in patients presenting to a urogynecology practice. Int. Urogynecology J. 2006, 17, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S.Y.; Samad-Soltani, T.; Hajebrahimi, S.; Sadeghi-Ghyassi, F.; Pashazadeh, F.; Abolhasanpour, N. Determining the risk factors and characteristics of de novo stress urinary incontinence in women undergoing pelvic organ prolapse surgery: A systematic review. Turk. J. Urol. 2020, 46, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhu, L.; Ding, J. The value of the preoperative 1-h pad test with pessary insertion for predicting the need for a mid-urethral sling following pelvic prolapse surgery: A cohort study. World J. Urol. 2016, 34, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, T.; Sullivan, G.; Leung, K.; Flynn, M. The negative predictive value of preoperative urodynamics for stress urinary incontinence following prolapse surgery. Int. Urogynecology J. 2019, 30, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Fernández, B.; Ramírez-Castillo, G.M.; Hernández-Hernández, D.; Castro-Díaz, D.M. Urodynamics Before Stress Urinary Incontinence Surgery in Modern Functional Urology. Eur. Urol. Focus 2019, 5, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchio, S.; Novara, L.; Sgro, L.G.; Rapetti, G.; Fuso, L.; Menato, G.; Biglia, N. Concomitant stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse surgery: Opportunity or overtreatment? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 250, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maigaard, S.; Forman, A.; Andersson, K.E. Digoxin inhibition of relaxation induced by prostacyclin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in small human placental arteries. Placenta 1985, 6, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Jiang, G.L.; Fu, X.L.; Yoshimura, M.; Sakanaka, K.; Norihisa, Y.; Mizowaki, T.; Shibuya, K.; Nagata, Y.; Hiraoka, M. The impact of overall treatment time on outcomes in radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2000, 28, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Vaidya, M.C. Mast cell and Mycobacterium leprae in experimental leprosy. Hansenol Int. 1982, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitti, V.W. Complications of midurethral slings and their management. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. J. Assoc. Urol. Can. 2012, 6 (Suppl. S2), S120–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agostini, A.; Bretelle, F.; Franchi, F.; Roger, V.; Cravello, L.; Blanc, B. Immediate complications of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT): Results of a French survey. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2006, 124, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.M.; Kahana, M.D.; Park, T.S. Intrathecal morphine for postoperative analgesia in children after selective dorsal root rhizotomy. Neurosurgery 1991, 28, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoryan, B.; Kasyan, G.; Pushkar, D. Autologous Slings in Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. Urogynecology J. 2024, 35, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groutz, A.; Gold, R.; Pauzner, D.; Lessing, J.B.; Gordon, D. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for the treatment of occult stress urinary incontinence in women undergoing prolapse repair: A prospective study of 100 consecutive cases. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2004, 23, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latthe, P.M.; Singh, P.; Foon, R.; Toozs-Hobson, P. Two routes of transobturator tape procedures in stress urinary incontinence: A meta-analysis with direct and indirect comparison of randomized trials. BJU Int. 2010, 106, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novara, G.; Artibani, W.; Barber, M.D.; Chapple, C.R.; Costantini, E.; Ficarra, V.; Hilton, P.; Nilsson, C.G.; Waltregny, D. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparative data on colposuspensions, pubovaginal slings, and midurethral tapes in the surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Eur. Urol. 2010, 58, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schachar, J.S.; Matthews, C.A. Robotic-assisted repair of pelvic organ prolapse: A scoping review of the literature. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Société Internationale d’Urologie. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).