Burden of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

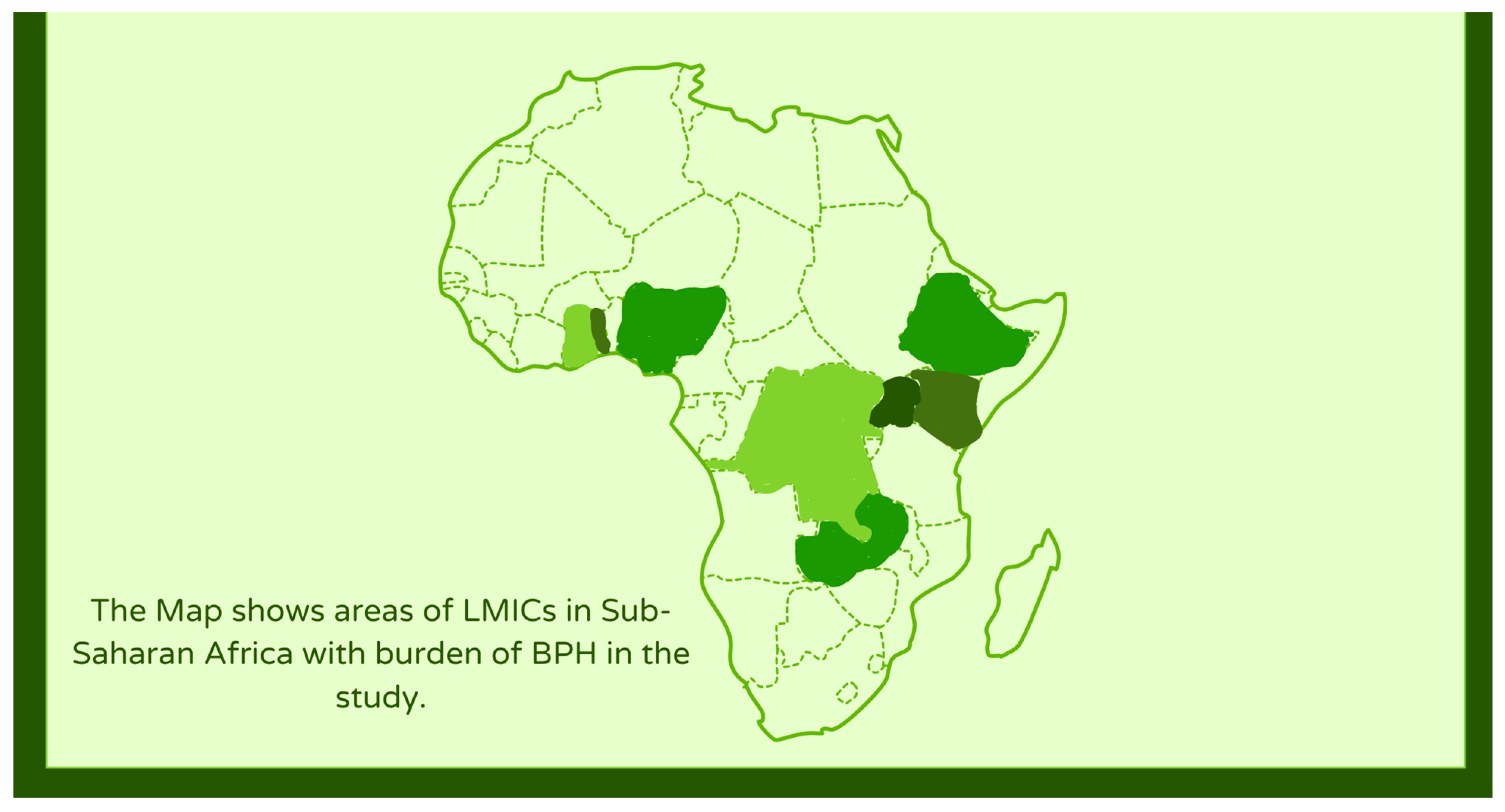

- Studies conducted in LMICs (limited to Sub-Saharan Africa) as defined by the World Bank.

- Studies reporting on the prevalence, impact, or management of BPH.

- Articles published in English.

- Studies conducted in HICs.

- Articles not focused on BPH.

- Non-peer-reviewed articles, editorials, and opinion pieces.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of BPH in LMICs

3.2. Cost Implications

3.3. Impact on Quality of Life

3.4. Management Practices

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Launer, B.M.; McVary, K.T.; Ricke, W.A.; Lloyd, G.L. The rising worldwide impact of benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int. 2021, 127, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugare, U.G.; Bassey, I.A.; Udosen, E.J.; Essiet, A.; Bassey, O.O. Management of lower urinary retention in a limited resource setting. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2014, 24, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asare, G.A.; Sule, D.S.; Oblitey, J.N.; Ntiforo, R.; Asiedu, B.; Amoah, B.Y.; Lamptey, E.L.; Afriyie, D.K.; Botwe, B.O. High degree of prostate related LUTS in a prospective cross-sectional community study in Ghana (Mamprobi). Heliyon 2021, 7, e08391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, J.S.; Bixler, B.R.; Dahm, P.; Goueli, R.; Kirkby, E.; Stoffel, J.T.; Wilt, T.J. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): AUA Guideline amendment 2023. J. Urol. 2023, 211, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.U.; Hindley, R.G.; Kalpee, A.; Demaire, C.; Woodward, E.; Binns, J.; Blisset, R. PMD27 Cost Comparison of Surgical Interventions to TREAT Lower Urinary TRACT Symptoms (LUTS) Secondary to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in the UK, Sweden, and South Africa. Value Health 2020, 23, S580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, J.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z. Global burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia in males aged 60–90 years from 1990 to 2019: Results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Urol. 2024, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awedew, A.F.; Han, H.; Abbasi, B.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Ahmed, M.B.; Almidani, O.; Amini, E.; Arabloo, J.; Argaw, A.M.; Athari, S.S.; et al. The global, regional, and national burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia in 204 countries and territories from 2000 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e754–e776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F.; Liu, G.X.; Guo, Y.S.; Zhu, H.Y.; He, D.L.; Qiao, X.M.; Li, X.H. Global, regional, and national incidence and year lived with disability for benign prostatic hyperplasia from 1990 to 2019. Am. J. Mens Health 2021, 15, 15579883211036786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, C.M.; Simms, M.S.; Maitland, N.J. Benign prostatic hyperplasia–what do we know? BJU Int. 2021, 127, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diyoke, K.; Yusuf, A.; Demirbas, E. Government expenditure and economic growth in lower middle income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa: An empirical investigation. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2017, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojewola, R.W.; Oridota, E.S.; Balogun, O.S.; Alabi, T.O.; Ajayi, A.I.; Olajide, T.A.; Tijani, K.H.; Jeje, E.A.; Ogunjimi, M.A.; Ogundare, E.O. Prevalence of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia amongst community-dwelling men in a South-Western Nigerian rural setting: A cross-sectional study. Afr. J. Urol. 2017, 23, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokkalingam, A.P.; Yeboah, E.D.; Demarzo, A.; Netto, G.; Yu, K.; Biritwum, R.B.; Tettey, Y.; Adjei, A.; Jadallah, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Prevalence of BPH and lower urinary tract symptoms in West Africans. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012, 15, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre, B.B.; Gebrie, M.; Bedru, M.; Bennat, V. Magnitude and associated factors of benign prostatic hyperplasia among male patients admitted at surgical ward of selected governmental hospitals in Sidamma region, Ethiopia 2021. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2024, 20, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvet, T.; Hayes, J.R.; Ferrara, S.; Goche, D.; Macmillan, R.D.; Singal, R.K. The burden of urological disease in Zomba, Malawi: A needs assessment in a sub-Saharan tertiary care center. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2020, 14, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, I.; Bayne, D.; Chang, H.; Jalloh, M.; Sharlip, I. Challenges facing the urologist in low-and middle-income countries. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 2987–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stothers, L.; Macnab, A.J.; Bajunirwe, F.; Mutabazi, S.; Berkowitz, J. Associations between the severity of obstructive lower urinary tract symptoms and care-seeking behavior in rural Africa: A cross-sectional survey from Uganda. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeh, E.I.; Ofoha, C.G.; Adewole, D.A.; Nnabugwu, I.I. A cost effective analysis of fixed-dose combination of dutasteride and tamsulosin compared with dutasteride monotherapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in Nigeria: A middle income perspective; using an interactive Markov model. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nneoma Igwe, C.; Israel Eshiet, U. An Analysis of Cases of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in a Tertiary Hospital in Eastern Nigeria: Incidence, Treatment, and Cost of Management. Asian J. Res. Rep. Urol. 2021, 4, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, M.O.; Geoffrey, O.M. Individual factors influencing uptake of benign prostate hyperplasia services among older men in Kenya. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namusonge, L.N.; Ngachra, J.O. Assessment of Factors Contributing to Delayed Surgeries in Enlarged Prostate Patients: A Survey at Kisumu County Referral Hospital. East Afr. J. Health Sci. 2021, 4, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stothers, L.; Mutabazi, S.; Mukisa, R.; Macnab, A.J. The burden of bladder outlet obstruction in men in rural Uganda. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1763–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bajunirwe, F.; Stothers, L.; Berkowitz, J.; Macnab, A.J. Prevalence estimates for lower urinary tract symptom severity among men in Uganda and sub-Saharan Africa based on regional prevalence data. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018, 12, E447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolani, M.A.; Suleiman, A.; Awaisu, M.; Abdulaziz, M.M.; Lawal, A.T.; Bello, A. Acute urinary tract infection in patients with underlying benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 36, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, H.H.; Shah, J.; Nyanja, T.A.; Shabani, J.S. Factors associated with depressive symptoms in patients with benign prostatic enlargement. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2023, 15, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeje, E.A.; Ojewola, R.W.; Nwofor, A.M.; Ogunjimi, M.A.; Alabi, T.O. Challenges in the management of benign prostatic enlargement in Nigeria. Nig. Qt. J. Hosp. Med. 2016, 26, 599–602. [Google Scholar]

- Zubair, A.; Davis, S.; Balogun, D.I.; Nwokeocha, E.; Chiedozie, C.A.; Jesuyajolu, D. A Scoping Review of the Management of Benign Prostate Hyperplasia in Africa. Cureus 2022, 14, e31135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, N.; Raji, S.; Amoo, A.; Adeleye-Idowu, S. Surgical Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in A Tertiary Health Centre. Alq. J. Med. App. Sci. 2022, 5, 606–610. [Google Scholar]

- Kyei, M.Y.; Mensah, J.E.; Morton, B.; Gepi-Attee, S.; Klufio, G.O.; Yeboah, E.D. Surgical management of BPH in Ghana: A need to improve access to transurethral resection of the prostate. East Afr. Med. J. 2012, 89, 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Etyang, A.O.; Munge, K.; Bunyasi, E.W.; Matata, L.; Ndila, C.; Kapesa, S.; Owiti, M.; Khandwalla, I.; Brent, A.J.; Tsofa, B.; et al. Burden of disease in adults admitted to hospital in a rural region of coastal Kenya: An analysis of data from linked clinical and demographic surveillance systems. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e216–e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campain, N.J.; MacDonagh, R.P.; Mteta, K.A.; McGrath, J.S. Global surgery—How much of the burden is urological? BJU Int. 2015, 116, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salako, A.A.; Badmus, T.A.; Owojuyigbe, A.M.; David, R.A.; Ndegbu, C.U.; Onyeze, C.I. Open prostatectomy in the management of benign prostate hyperplasia in a developing economy. Open J. Urol. 2016, 6, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, L.; Jalloh, M.; Houlgatte, A.; Ndoye, M.; Diallo, A.; Labou, I.; Mane, I.L.; Mbodji, M.; Gueye, S.M. Simulation Training in Endo-urology: A New Opportunity for Training in Senegal. Curr. Bladder Dysfunct. Rep. 2020, 15, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieudonne, Z.O.J.; Nedjim, S.A.; Kifle, A.T.; Gebreselassie, K.H.; Gnimdou, B.; Mahamat, M.A.; Emmanuel, M.; Noel, C.; Khassim, N.A.; Khalid, A.; et al. Surgical Advances in Treating Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Africa: What about the Endoscopic Approach? Urology 2024, 189, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeboah, E.D.; Hsing, A.W. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer in africans and africans in the diaspora. J. West. Afr. Coll. Surg. 2016, 6, x–xviii. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alhasan, S.U.; Aji, S.A.; Mohammed, A.Z.; Malami, S. Transurethral resection of the prostate in Northern Nigeria, problems and prospects. BMC Urol. 2008, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rimtebaye, K.; Mpah, E.H.; Tashkand, A.Z.; Sillong, F.D.; Kaboro, M.; Niang, L.; Gueye, S.M. Epidemiological, Clinical and Management of Benign Prostatic Hypertrophia in Urologie Department in N’Djamena, Chad. Open J. Urol. 2017, 7, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kpatcha, T.M.; Tchangai, B.; Tengue, K.; Alassani, F.; Botcho, G.; Darre, T.; Leloua, E.; Sikpa, K.H.; Sewa, E.V.; Anoukoum, T.; et al. Experience with Open Prostatectomy in Lomé, Togo. Open J. Urol. 2016, 6, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagayogo, N.A.; Faye, M.; Sine, B.; Sarr, A.; Ndiaye, M.; Ndiath, A.; Ndour, N.S.; Traore, A.; Erradja, F.; Faye, S.T.; et al. Giant benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): Epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects. Afr. J. Urol. 2021, 27, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Avion, K.P.; Aguia, B.; Zouan, F.; Alloka, V.; Kamara, S.; Dje, K. Practice of Endo-Urology in the Centre of Ivory Coast: Overview and Results. Open J. Urol. 2023, 13, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Year of Publication | Country | Design | General Objective of BPH/LUTS Study | Sample Size (Subjects) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asare et al. [3] | 2021 | Ghana | Prospective cross-sectional study | Prevalence of LUTSs | 111 |

| Ojewola. et al. [12] | 2017 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | LUTSs/QOL | 615 |

| Chokkalingam et al. [13] | 2012 | Ghana | Prospective cross-sectional study | Prevalence of LUTSs/BPH | 950 |

| Gebre et al. [14] | 2021 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Prevalence of BPH | 143 |

| Juvet et al. [15] | 2020 | Malawi | Retrospective study | LUTSs/Management | 440 |

| Metzler et al. [16] | 2020 | Multinational | Survey | Prevalence BPH | 114 |

| Stothers et al. [17] | 2017 | Uganda | Cross-sectional study | Cost burden of BPH | 473 |

| Udeh et al. [18] | 2016 | Nigeria | Interactive Markov model | Cost burden of BPH | 2.9 million |

| Nneoma Igwe et al. [19] | 2021 | Nigeria | Retrospective, descriptive | Prevalence/Cost burden of BPH | 102 |

| Vincent et al. [20] | 2021 | Kenya | Mixed method | Cost burden of BPH | 387 |

| Namusonge et al. [21] | 2021 | Kenya | Descriptive survey | Cost burden of BPH | 50 |

| Stothers et al. [22] | 2016 | Uganda | Survey | LUTSs/QOL | 238 |

| Bajunirwi et al. [23] | Uganda | Cross-sectional survey | Prevalence/QOL | 250 | |

| Tolani et al. [24] | 2020 | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Prevalence/QOL | 118 |

| Abdalla et al. [25] | 2023 | Kenya | Cross-sectional study | QOL | 308 |

| Jeje et al. [26] | 2016 | Nigeria | Review | LUTSs/Management | |

| Zubair et al. [27] | 2022 | Multinational | Scoping review | LUTSs/Management | 2999 |

| Idowu et al. [28] | 2022 | Nigeria | Retrospective study | LUTSs/Management | 151 |

| Kyei et al. [29] | 2012 | Ghana | Prospective cohort study | LUTSs/Management | 114 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Société Internationale d’Urologie. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cassell, A.; Sine, B.; Jalloh, M.; Gravas, S. Burden of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Soc. Int. Urol. J. 2024, 5, 320-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj5050051

Cassell A, Sine B, Jalloh M, Gravas S. Burden of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal. 2024; 5(5):320-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj5050051

Chicago/Turabian StyleCassell, Ayun, Babacar Sine, Mohamed Jalloh, and Stavros Gravas. 2024. "Burden of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)" Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal 5, no. 5: 320-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj5050051

APA StyleCassell, A., Sine, B., Jalloh, M., & Gravas, S. (2024). Burden of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Société Internationale d’Urologie Journal, 5(5), 320-329. https://doi.org/10.3390/siuj5050051