Recommendations Following Hospitalization for Acute Exacerbation of COPD—A Consensus Statement of the Polish Respiratory Society

Highlights

- A multidisciplinary team should be involved in developing discharge instructions after hospitalization for a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation to ensure clear, consistent, and comprehensive documentation.

- Discharge instructions should be reviewed with the patient during hospitalization and supplemented with educational materials provided separately from the discharge summary.

- A personalized action plan for managing future exacerbations should be included.

- The discharge summary must specify the date of the follow-up appointment and contain a prescription for inhaled medications.

- This document provides guidance for Polish healthcare professionals on how to create effective discharge instructions after hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation.

- The recommendations will support healthcare administrators in Poland in optimizing the process of preparing discharge summaries for patients hospitalized due to COPD exacerbations.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Content of Recommendations

- Review of the discharge summary.

- Documentation of the exacerbation (medical records/individual medical care plan)

- Discussion with the patient regarding the reason for hospitalization and further diagnostic and therapeutic management.

- Assessment of symptom severity (mMRC [modified Medical Research Council]/COPD Assessment Test [CAT]).

- Evaluation of physical activity.

- Verification of vaccination status and discussion of recommended vaccinations

- Assessment of comorbidities:

- Indications for further diagnostic evaluation;

- Evaluation of control of established comorbidities;

- Assessment of cardiovascular risk.

- Review of current medications, with attention to modifications introduced during hospitalization, including tapering schedules for medications used in the exacerbation (e.g., oral corticosteroids, antibiotics).

- Assessment of inhaler technique.

- Measurement of oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry.

- Smoking cessation intervention for active smokers.

- Patient education in areas of care identified as important, including dietary counseling.

- Modification or issuance of a written action plan.

- Planning of the next follow-up visit and diagnostic tests (including evaluation of indications for a pulmonology consultation).

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BR | Backup Rate |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| EPAP | Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure |

| GOLD | Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease |

| HNB | Heat-Not-Burn |

| IPAP | Inspiratory Positive Airway Pressure |

| PRS | Polish Respiratory Society |

| RSV | Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| ST mode | Spontaneous/Timed mode |

| Ti | Inspiratory Time |

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2026 Report. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2026-gold-report/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- de Oca, M.M.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Celli, B.; Aaron, S.D.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Amaral, A.F.S.; Mannino, D.; Zheng, J.; Salvi, S.; Obaseki, D.; et al. The global burden of COPD: Epidemiology and effect of prevention strategies. Lancet Respir. Med. 2025, 13, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapy Potrzeb Zdrowotnych—Baza Analiz Systemowych i Wdrożeniowych. Available online: https://basiw.mz.gov.pl/analizy/problemy-zdrowotne/przewlekla-obturacyjna-choroba-pluc/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Celli, B.R.; Wedzicha, J.A. Update on Clinical Aspects of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, L.M.; Celli, B.R.; Agustí, A.; Criner, G.J.; Dransfield, M.T.; Divo, M.; Krishnan, J.K.; Lahousse, L.; de Oca, M.M.; Salvi, S.S.; et al. COPD and multimorbidity: Recognising and addressing a syndemic occurrence. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J.; Celli, B.R. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 1165–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, P.W.; Lubiński, W. Health state and the quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Poland: A study using the EuroQoL-5D questionnaire. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2012, 122, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divo, M.; Cote, C.; de Torres, J.P.; Casanova, C.; Marin, J.M.; Pinto-Plata, V.; Zulueta, J.; Cabrera, C.; Zagaceta, J.; Hunninghake, G.; et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłkowska-Dymanowska, J.; Białas, A.J.; Zalewska-Janowska, A.; Górski, P.; Piotrowski, W.J. Underrecognized comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, R.; Johannessen, A.; Benediktsdottir, B.; Gislason, T.; Buist, A.S.; Gulsvik, A.; Sullivan, S.D.; Lee, T.A. Present and future costs of COPD in Iceland and Norway: Results from the BOLD study. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapy Potrzeb Zdrowotnych: Wnioski i Rekomendacje. Choroby Układu Oddechowego (Przewlekłe). Available online: https://mpz.mz.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/sites/4_old_0212/2018/05/uklad_oddechowy_20180531.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Balaban, R.B.; Weissman, J.S.; Samuel, P.A.; Woolhandler, S. Redefining and redesigning hospital discharge to enhance patient care: A randomized controlled study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1228–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, S.; Jackson, A.T.; Schnipper, J.L.; Coleman, E.A. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: A review of key issues for hospitalists. J. Hosp. Med. 2007, 2, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, C.L.; Poon, E.G.; Karson, A.S.; Ladak-Merchant, Z.; Johnson, R.E.; Maviglia, S.M.; Gandhi, T.K. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 143, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimsett, J.; Harper, A.; Jones, P. Review article: Components of a good quality discharge summary: A systematic review. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2014, 26, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weetman, K.; Spencer, R.; Dale, J.; Scott, E.; Schnurr, S. What makes a “successful” or “unsuccessful” discharge letter? Hospital clinician and General Practitioner assessments of the quality of discharge letters. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weetman, K.; Dale, J.; Scott, E.; Schnurr, S. Adult patient perspectives on receiving hospital discharge letters: A corpus analysis of patient interviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, P.; Vandijck, D.; Degroote, S.; Peleman, R.; Verhaeghe, R.; Mortier, E.; Hallaert, G.; Van Daele, S.; Buylaert, W.; Vogelaers, D. Communication in healthcare: A narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2015, 69, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Simply Put: A Guide for Creating Easy-to-Understand Materials. 2010. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11938 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Wittink, H.; Oosterhaven, J. Patient education and health literacy. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2018, 38, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.N.; Cornelison, S.; Woods, J.A.; Hanania, N.A. Managing hospitalized patients with a COPD exacerbation: The role of hospitalists and the multidisciplinary team. Postgrad. Med. 2022, 134, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalakuhan, B.; Adams, S.G. Improving outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The role of the interprofessional approach. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heide, I.; Poureslami, I.; Shum, J.; Goldstein, R.; Gupta, S.; Aaron, S.; Lavoie, K.L.; Poirier, C.; FitzGerald, J.M.; on behalf of the Canadian Airways Health Literacy Study Group. Factors Affecting Health Literacy as Related to Asthma and COPD Management: Learning from Patient and Health Care Professional Viewpoints. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2021, 5, e179–e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruffydd-Jones, K.; Langley-Johnson, C.; Dyer, C.; Badlan, K.; Ward, S. What are the needs of patients following discharge from hospital after an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? Prim. Care Respir. J. 2007, 16, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, M.; DeJean, D.; Simeonov, D.; Smith, A. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: A systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2012, 12, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hahn-Goldberg, S.; Jeffs, L.; Troup, A.; Kubba, R.; Okrainec, K. “We are doing it together”; The integral role of caregivers in a patients’ transition home from the medicine unit. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okrainec, K.; Hahn-Goldberg, S.; Abrams, H.; Bell, C.M.; Soong, C.; Hart, M.; Shea, B.; Schmidt, S.; Troup, A.; Jeffs, L. Patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives on factors that influence understanding of and adherence to hospital discharge instructions: A qualitative study. CMAJ Open 2019, 7, E478–E483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Cruz, J.; Brooks, D. Interventions to Support Informal Caregivers of People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Literature Review. Respiration 2021, 100, 1230–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.; Mansfield, E.; Boyes, A.W.; Waller, A.; Sanson-Fisher, R.; Regan, T. Involvement of informal caregivers in supporting patients with COPD: A review of intervention studies. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2016, 11, 1587–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, D.; Cozzolino, S.; D’Amato, G.; Cocco, G.; Sena, A.; Martucci, P.; Ferraro, E.; Mancini, A.A. Sharing knowledge is the key to success in a patient-physician relationship: How to produce a patient information leaflet on COPD. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2008, 69, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, P.C.; Roche, N.; Neukirch, F.; Radeau, T.; Perez, T.; Terrioux, P.; Ostinelli, J.; Pouchain, D.; Huchon, G. The effect of an information leaflet upon knowledge and awareness of COPD in potential sufferers. A randomized controlled study. Respiration 2008, 76, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis, J.; Gich, I.; Pedersen, S.; on behalf of the Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team (ADMIT). Systematic Review of Errors in Inhaler Use: Has Patient Technique Improved Over Time? Chest 2016, 150, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukić Dugac, A.; Vergles, M.; Škrinjarić Cincar, S.; Kardum, L.B.; Lampalo, M.; Popović-Grle, S.; Ostojić, J.; Vuksan-Ćusa, T.T.; Vrbica, Ž.; Vukovac, E.L.; et al. Are We Missing the Opportunity to Disseminate GOLD Recommendations Through AECOPD Discharge Letters? Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, O.S.; Lavorini, F.; Marshall, J.; Dunlop, W.C.N.; Heron, L.; Farrington, E.; Dekhuijzen, R. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: A systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone-Banks, J.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Hartmann-Boyce, J. Print-based self-help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD001118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno-Santos, E.; Frei, A.; Steurer-Stey, C.; de Batlle, J.; Rabinovich, R.A.; Raste, Y.; Hopkinson, N.S.; Polkey, M.I.; van Remoortel, H.; Troosters, T.; et al. Determinants and outcomes of physical activity in patients with COPD: A systematic review. Thorax 2014, 69, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, C.; Bayles, M.P.; Hamm, L.F.; Hill, K.; Holland, A.; Limberg, T.M.; Spruit, M.A. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Exercise Prescription in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Review of Selected Guidelines: An Official Statement from the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2016, 36, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C.L.; Alison, J.A.; Carlin, B.; Jenkins, A.R.; Cox, N.S.; Bauldoff, G.; Bhatt, S.P.; Bourbeau, J.; Burtin, C.; Camp, P.G.; et al. Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Adults with Chronic Respiratory Disease: An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, e7–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Bian, Y.; Zhou, X.; Hou, G. Global prevalence of malnutrition in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, E.; Williams, E.M. Managing malnutrition in COPD: A review. Respir. Med. 2021, 176, 106248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattermann Pereira, T.; Lima, J.; Silva, F.M. Undernutrition is associated with mortality, exacerbation, and poorer quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2022, 46, 977–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, J.A.; Tang, J.N.; Poole, P.; Wood-Baker, R. Pneumococcal vaccines for preventing pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 1, CD001390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopsaftis, Z.; Wood-Baker, R.; Poole, P. Influenza vaccine for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 6, CD002733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Wen, F.; Chen, J. Effects of influenza vaccination on clinical outcomes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 68, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkat-Berkani, R.; Wilkinson, T.; Buchy, P.; Dos Santos, G.; Stefanidis, D.; Devaster, J.-M.; Meyer, N. Seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with COPD: A systematic literature review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017, 17, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aka Aktürk, Ü.; Görek Dilektaşlı, A.; Şengül, A.; Salepçi, B.M.; Oktay, N.; Düger, M.; Taşyıkan, H.A.; Koçak, N.D. Influenza and Pneumonia Vaccination Rates and Factors Affecting Vaccination among Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Balk. Med. J. 2017, 34, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego PZH—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy, Zakład Epidemiologii Chorób Zakaźnych i Nadzoru; Główny Inspektorat Sanitarny, Departament Przeciwepidemiczny i Ochrony Sanitarnej Granic. Szczepienia Ochronne w Polsce w 2021 Roku. Available online: https://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/2021/Sz_2021.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Lenferink, A.; Brusse-Keizer, M.; van der Valk, P.D.; Frith, P.A.; Zwerink, M.; Monninkhof, E.M.; Van Der Palen, J.; Effing, T.W. Self-management interventions including action plans for exacerbations versus usual care in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD011682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardener, A.C.; Ewing, G.; Kuhn, I.; Farquhar, M. Support needs of patients with COPD: A systematic literature search and narrative review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2018, 13, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.P.; Lai, C.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Chang, Y.C.; Lin, M.C.; Chong, I.W.; Sheu, C.C.; Wei, Y.F.; Chu, K.A.; Tsai, J.R.; et al. Mortality and vertebral fracture risk associated with long-term oral steroid use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2019, 16, 1479973119838280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calverley, P.M. Respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 47, 26s–30s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, B.R.; Howard, L.S.; Earis, J.; Mak, V. British Thoracic Society Guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2017, 4, e000170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliwiński, P.; Górecka, D.; Jassem, E.; Pierzchała, W. Zalecenia Polskiego Towarzystwa Chorób Płuc dotyczące rozpoznawania i leczenia przewlekłej obturacyjnej choroby płuc. Pneumonol. Alergol. Pol. 2014, 82, 227–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavish, R.; Levy, A.; Dekel, O.K.; Karp, E.; Maimon, N. The Association Between Hospital Readmission and Pulmonologist Follow-up Visits in Patients with COPD. Chest 2015, 148, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Quality Ontario. Effect of Early Follow-Up After Hospital Discharge on Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2017, 17, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Recommendation | Voting Outcome |

|---|---|---|

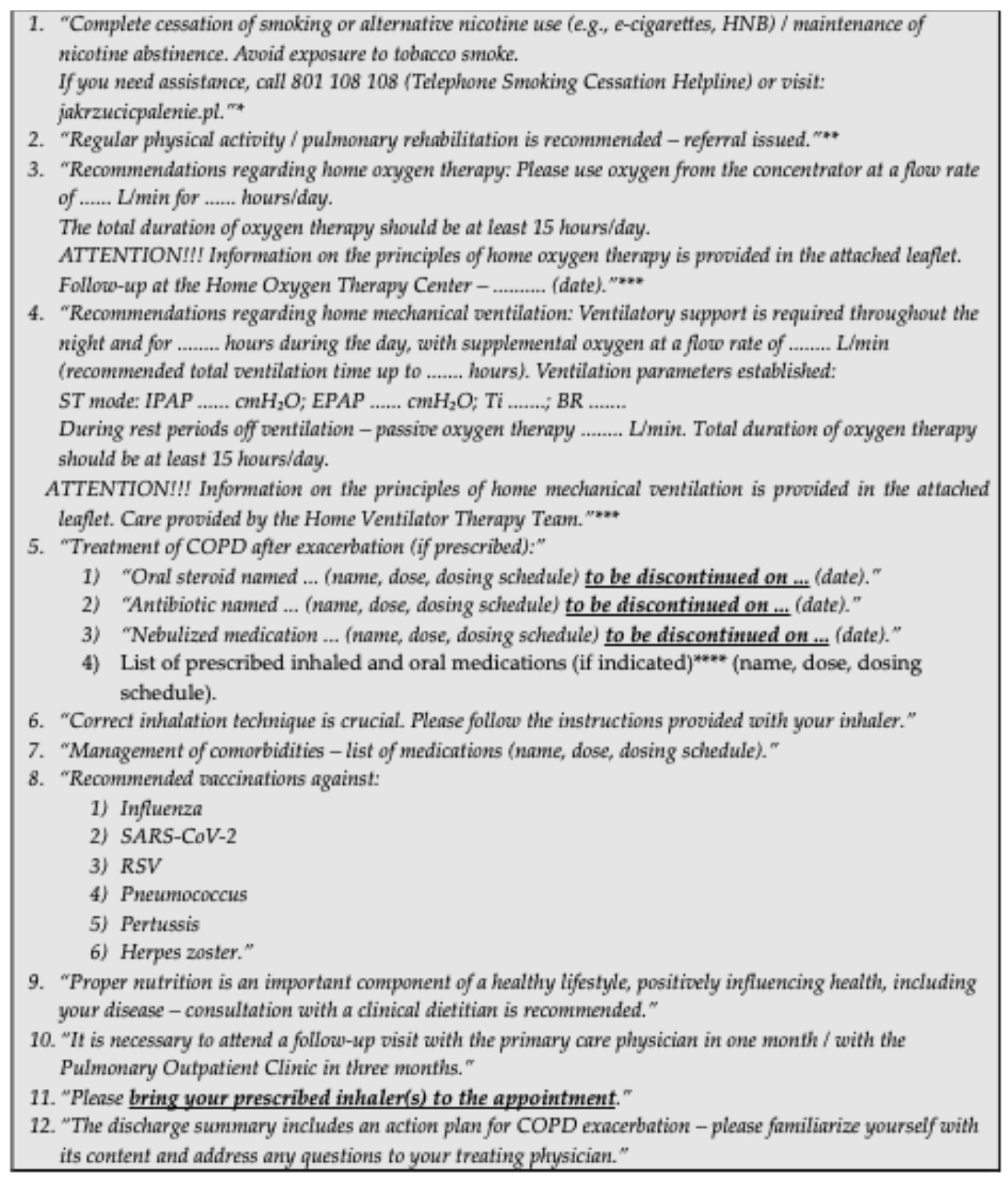

| 1 | We recommend that the overall layout and formatting of the discharge summary be carefully designed to ensure a high level of readability for both healthcare professionals and patients. | Consensus in favor |

| 2 | We recommend that the preparation of the discharge summary involve a multidisciplinary team (physician, nurse, physiotherapist, and, optimally, also a dietitian and clinical psychologist). This will allow integration of discharge documents prepared by individual team members into a coherent whole. | Consensus in favor |

| 3 | We recommend that discharge recommendations be discussed with the patient during the hospital stay. | Consensus in favor |

| 4 | We recommend that discharge recommendations be supplemented with additional educational materials provided independently of the discharge summary. | Consensus in favor |

| 5 | We recommend that discharge recommendations include instructions on the correct inhaler technique. A standardized template dedicated to a specific inhaler should be used as an additional educational material provided independently of the discharge summary. | Consensus in favor |

| 6 | We recommend that discharge recommendations for patients using tobacco or nicotine products include information on the necessity of and strategies for cessation. A standardized template should also be used as an additional educational material provided independently of the discharge summary. | Consensus in favor |

| 7 | We recommend that discharge recommendations include information on physical activity and pulmonary rehabilitation. A standardized template should be used as an additional educational material provided independently of the discharge summary. | Consensus in favor |

| 8 | We recommend that discharge recommendations include a referral for dietary counseling. | Consensus in favor |

| 9 | We recommend that discharge recommendations include information on vaccinations. A standardized template should also be used as an additional educational material provided independently of the discharge summary. | Consensus in favor |

| 10 | We recommend that discharge recommendations include an action plan for COPD exacerbation. A standardized template of such a plan should be provided independently of the discharge summary. | Consensus in favor |

| 11 | We recommend that discharge recommendations emphasize any changes to baseline COPD therapy and management of comorbidities. | Consensus in favor |

| 12 | We recommend that patients with COPD and concomitant respiratory failure receive discharge recommendations regarding home oxygen therapy or home mechanical ventilation. A standardized template should be used as an additional educational material provided independently of the discharge summary. | Consensus in favor |

| 13 | We recommend that discharge recommendations include information on the necessity of bringing inhaler(s) to the follow-up visit. | Consensus in favor |

| 14 | We recommend that the discharge summary include information on the necessity of attending a follow-up visit. | Consensus in favor |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Polish Respiratory Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Białas, A.J.; Barczyk, A.; Damps-Konstańska, I.; Kania, A.; Kuziemski, K.; Ledwoch, J.; Rasławska, K.; Czajkowska-Malinowska, M. Recommendations Following Hospitalization for Acute Exacerbation of COPD—A Consensus Statement of the Polish Respiratory Society. Adv. Respir. Med. 2026, 94, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010004

Białas AJ, Barczyk A, Damps-Konstańska I, Kania A, Kuziemski K, Ledwoch J, Rasławska K, Czajkowska-Malinowska M. Recommendations Following Hospitalization for Acute Exacerbation of COPD—A Consensus Statement of the Polish Respiratory Society. Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 2026; 94(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiałas, Adam Jerzy, Adam Barczyk, Iwona Damps-Konstańska, Aleksander Kania, Krzysztof Kuziemski, Justyna Ledwoch, Krystyna Rasławska, and Małgorzata Czajkowska-Malinowska. 2026. "Recommendations Following Hospitalization for Acute Exacerbation of COPD—A Consensus Statement of the Polish Respiratory Society" Advances in Respiratory Medicine 94, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010004

APA StyleBiałas, A. J., Barczyk, A., Damps-Konstańska, I., Kania, A., Kuziemski, K., Ledwoch, J., Rasławska, K., & Czajkowska-Malinowska, M. (2026). Recommendations Following Hospitalization for Acute Exacerbation of COPD—A Consensus Statement of the Polish Respiratory Society. Advances in Respiratory Medicine, 94(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010004