Exploring the Risk: Investigating the Association Between Elderly-Onset Sarcoidosis (EOS) and Malignancy

Highlights

- Patients with EOS were more frequently female and exhibited a markedly higher prevalence of prior malignancy (OR ≈8.0) compared to younger-onset counterparts. First bullet.

- Increasing age at sarcoidosis diagnosis was independent predictor of prior malignancy history, whereas sex, smoking history, and cardiometabolic profile did not significantly influence the likelihood of pre-existing neoplasia.

- In elderly patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis—particularly those with a history of malignancy—histological confirmation is crucial to distinguish sarcoidosis from tumor recurrence or metastasis due to overlapping radiological findings.

- The increased prevalence of malignancy in elderly-onset sarcoidosis appears predominantly age-related rather than EOS-specific, emphasizing the need for age-adjusted risk assessment and cautious consideration of targeted cancer evaluation in future prospective studies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

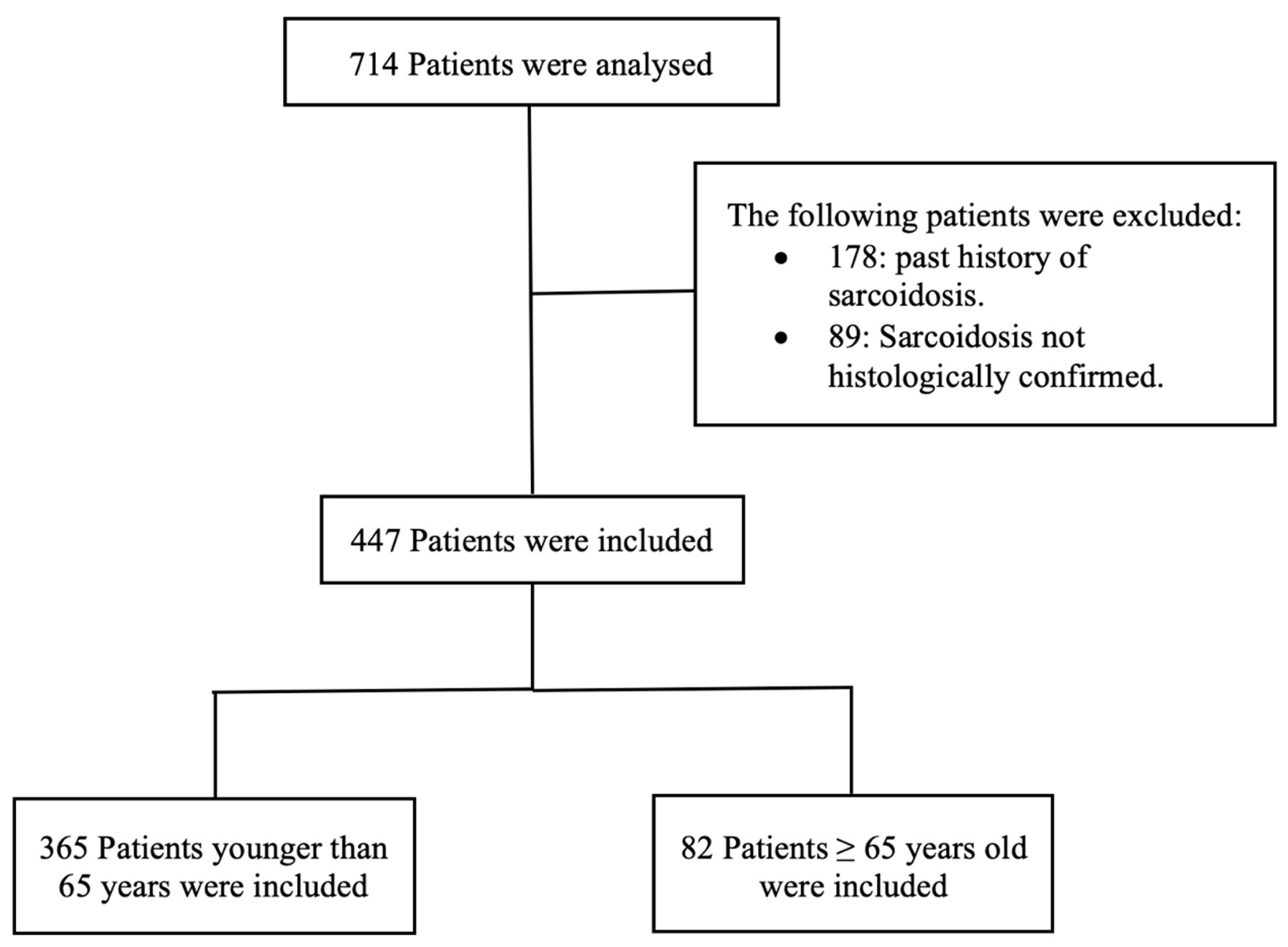

2.1. Patients

- Control group (younger-onset sarcoidosis): patients younger than 65 years old.

- Case group (elderly-onset sarcoidosis): patients 65 years old and older (EOS).

- Demographic and relevant clinical data: age, sex, smoking status, hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), medical histories other than cancer, diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO), forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), and forced vital capacity (FVC).

- Sarcoidosis: leading symptoms, location of the enlarged lymph nodes, radiological stage of the pulmonary sarcoidosis, diagnostic method of the sarcoidosis, and finally initiation of the treatment of the sarcoidosis after multidisciplinary discussion (MDD).

- History of malignant tumors before the sarcoidosis diagnosis, when positive: type of malignancy, staging, treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy), and average time between both malignancy and development of sarcoidosis.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| BA | Bronchial asthma |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DLCO | Diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| EBB | Endobronchial biopsy |

| EBUS-TBNA | Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration |

| EOS | Elderly-onset sarcoidosis |

| FEV1 | Forced expiratory volume in 1 second |

| FVC | Forced vital capacity |

| HOV | Hoarseness of voice |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| IRB | Institutional research board |

| LN | Lymph node |

| MDD | Multidisciplinary discussion |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| sIL2 | Soluble Interleukin-2 Receptor |

| TH1 | T-helper Cell Type 1 |

| VATS | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery |

References

- Iannuzzi, M.C.; Fontana, J.R. Sarcoidosis: Clinical Presentation, Immunopathogenesis, and Therapeutics. JAMA 2011, 305, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Rossi, G.; Trisolini, R.; Sverzellati, N.; Baughman, R.P.; Wells, A.U. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, M.; Bravi, F.; Gasparini, S.; La Vecchia, C.; Gabrielli, A.; Wells, A.U.; Renzoni, E.A. Sarcoidosis and Cancer Risk: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Chest 2015, 147, 778–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, R.P.; Field, S.; Costabel, U.; Crystal, R.G.; Culver, D.A.; Drent, M.; Judson, M.A.; Wolff, G. Sarcoidosis in America. Analysis Based on Health Care Use. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkema, E.V.; Cozier, Y.C. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: Recent estimates of incidence, prevalence and risk factors. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siltzbach, L.E.; James, D.G.; Neville, E.; Turiaf, J.; Battesti, J.P.; Sharma, O.P.; Hosoda, Y.; Mikami, R.; Odaka, M. Course and prognosis of sarcoidosis around the world. Am. J. Med. 1974, 57, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, E.; Walker, A.N.; James, D.G. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: An analysis of 818 patients. Q. J. Med. 1983, 52, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mayock, R.L.; Bertrand, P.; Morrison, C.E.; Scott, J.H. Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am. J. Med. 1963, 35, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, R.P.; Teirstein, A.S.; Judson, M.A.; Rossman, M.D.; Yeager, H.; Bresnitz, E.A.; DePalo, L.; Hunninghake, G.; Iannuzzi, M.C.; Johns, C.J.; et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 1885–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Azuma, A.; Abe, S.; Usuki, J.; Kudoh, S.; Sugisaki, K.; Oritsu, M.; Nukiwa, T. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in Japan. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byg, K.E.; Milman, N.; Hansen, S. Sarcoidosis in Denmark 1980–1994. A registry-based incidence study comprising 5536 patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003, 20, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jamilloux, Y.; Bonnefoy, M.; Valeyre, D.; Varron, L.; Broussolle, C.; Sève, P. Elderly-onset sarcoidosis: Prevalence, clinical course, and treatment. Drugs Aging 2013, 30, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orimo, H.; Ito, H.; Suzuki, T.; Araki, A.; Hosoi, T.; Sawabe, M. Reviewing the definition of “elderly”. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2006, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Rivas, M.; Corbella, X.; Mañá, J. Elderly sarcoidosis: A comparative study from a 42-year single-centre experience. Respir. Med. 2019, 152, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, L.; Pamulapati, S.; Barlas, A.; Aqeel, A. Elderly Onset Sarcoidosis: A Case Report. Cureus 2021, 13, e20443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, D.; Marzouk, S.; Snoussi, M.; Jallouli, M.; Gouiaa, N.; Boudawara, T.; Bahloul, Z. Retrospective study of elderly onset sarcoidosis in Tunisian patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffuse Lung Dis. 2021, 38, e2021016. [Google Scholar]

- Brincker, H.; Wilbek, E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br. J. Cancer 1974, 29, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jammal, T.; Pavic, M.; Gerfaud-Valentin, M.; Jamilloux, Y.; Sève, P. Sarcoidosis and Cancer: A Complex Relationship. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 594118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rømer, F.K.; Hommelgaard, P.; Schou, G. Sarcoidosis and cancer revisited: A long-term follow-up study of 555 Danish sarcoidosis patients. Eur. Respir. J. 1998, 12, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Balkwill, F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 1683, 454, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brincker, H. Sarcoid Reactions and Sarcoidosis in Hodgkin’s Disease and Other Malignant Lymphomata. Br. J. Cancer 1972, 26, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincker, H. The sarcoidosis-lymphoma syndrome. Br. J. Cancer 1986, 54, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arish, N.; Kuint, R.; Sapir, E.; Levy, L.; Abutbul, A.; Fridlender, Z.; Laxer, U.; Berkman, N. Characteristics of Sarcoidosis in Patients with Previous Malignancy: Causality or Coincidence? Respiration 2017, 93, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.A.; Pavithran, K.; Jose, W.M.; Vallonthaiel, A.G.; George, D.R.; Sudhakar, N. Case series of concurrent occurrence of sarcoidosis and breast cancer—A diagnostic dilemma. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 35, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorucci, F.; Conti, V.; Lucantoni, G.; Patrizi, A.; Fiorucci, C.; Giannunzio, G.; Di Michele, L. Sarcoidosis of the breast: A rare case report and a review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 10, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen Aubart, F.; Lhote, R.; Amoura, A.; Valeyre, D.; Haroche, J.; Amoura, Z.; Lebrun-Vignes, B. Drug-induced sarcoidosis: An overview of the WHO pharmacovigilance database. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 288, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobak, S.; Yildiz, F.; Semiz, H.; Orman, M. Elderly-onset Sarcoidosis: A Single Center Comparative Study. Reumatol. Clínica (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 16, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Alvarez, R.; Brito-Zerón, P.; Kostov, B.; Feijoo-Massó, C.; Fraile, G.; Gómez-de-la-Torre, R.; De-Escalante, B.; López-Dupla, M.; Alguacil, A.; Chara-Cervantes, J.; et al. Systemic phenotype of sarcoidosis associated with radiological stages. Analysis of 1230 patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 69, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Younger-Onset N = 365 | Elderly-Onset N = 82 | Crude OR (95% CI) | p Value | AOR (95% CI) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||||

| Age: median [IQR] | 47 [23–63] | 69 [65–84] | p ≤ 0.001 | ___ | ____ | |||

| Sex | r (1) | r (1) | ||||||

| 131 | 35.9% | 45 | 54.9% | 2.2 (1.3–3.5) | 0.002 | 2.1 (1.0–4.3) | 0.041 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| 148 | 53% | 25 | 45.5% | r (1) | r (1) | ||

| 66 | 23.7% | 27 | 49.1% | 2.4 (1.3–4.4) | 0.005 | 1.8 (0.9–3.9) | 0.117 |

| 65 | 23.3% | 3 | 5.5% | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 0.039 | 0.2 (0.06–0.9) | 0.044 |

| HTN | 72 | 19.8% | 59 | 75.6% | 12.6 (7.0–2.4) | ≤0.001 | 8.1 (3.9–16.8) | ≤0.001 |

| DM | 30 | 8.3% | 23 | 30.3% | 4.8 (2.6–8.9) | ≤0.001 | 3.3 (1.3–8.7) | 0.013 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 | 1.6% | 8 | 9.8% | 6.5 (2.2–19.2) | 0.001 | 3.9 (0.7–21.7) | 0.121 |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 | 3.0% | 6 | 7.3% | 2.5 (0.9–7.1) | 0.075 | ___ | |

| OSA | 10 | 2.7% | 0 | 0.0% | - | 0.220 | ___ | |

| COPD | 6 | 1.6% | 6 | 7.3% | 4.7 (1.5–15.0) | 0.009 | 6.0 (1.1–32.0) | 0.038 |

| Bronchial asthma (BA) | 28 | 7.7% | 2 | 2.4% | 0.3 (0.1–1.3) | 0.106 | ___ | |

| Younger-Onset N = 365 | Elderly-Onset N = 82 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Leading symptoms | |||||

| 80 | 22.2% | 20 | 24.7% | 0.623 |

| 137 | 38.0% | 23 | 28.4% | 0.106 |

| 70 | 19.4% | 41 | 50.6% | 0.001 |

| 45 | 12.5% | 2 | 2.5% | 0.08 |

| 49 | 13.6% | 2 | 2.5% | 0.005 |

| 10 | 2.8% | 3 | 3.7% | 0.714 |

| 8 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.360 |

| 2 | 0.6% | 1 | 1.2% | p: 0.456 a |

| 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | p: 1 a |

| 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | p: 1 a |

| 3 | 0.8% | 1 | 1.2% | p: 0.556 a |

| 3 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | p: 1 a |

| 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | p: 1 a |

| 1 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | p: 1 a |

| CT chest morphological signs | |||||

| 343 | 94.5% | 73 | 89.0% | 0.070 |

| 221 | 61.0% | 46 | 56.1% | 0.408 |

| |||||

| 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 2.5% | ≤0.001 * |

| 146 | 40.2% | 37 | 45.7% | |

| 193 | 53.2% | 27 | 33.3% | |

| 19 | 5.2% | 10 | 12.3% | |

| 5 | 1.4% | 5 | 6.2% | |

| Lung function parameters | |||||

| 3.19 (0.93) | 2.27 (0.85) | ≤0.001 b | ||

| 90 (4–138) | 87 (27–139) | 0.270 c | ||

| 3.8 (0.37–89) | 2.7 (0.9–4.9) | ≤0.001 c | ||

| 90 (12–139) | 84 (1.9–123) | 0.117 c | ||

| 77 (26–132) | 61 (10–108) | ≤0.001 c | ||

| Younger-Onset N = 365 | Elderly-Onset N = 82 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Diagnostic methods | |||||

| |||||

| 265 | 72.6% | 50 | 61% | 0.037 |

| 44 | 12.1% | 2 | 2.4% | 0.010 |

| 71 | 19.5% | 1 | 1.2% | 0.001 |

| 147 | 40.3% | 21 | 25.6% | 0.013 |

| 34 | 9.3% | 12 | 14.6% | 0.152 |

| 4 | 1.1% | 4 | 4.9% | 0.041 a |

| 3 | 0.8% | 1 | 1.3% | 0.557 a |

| 1 | 0.3% | 2 | 2.4% | 0.088 a |

| Treatment after multidisciplinary discussion (MDD) | 127 | 35.1% | 32 | 39.5% | 0.453 |

| Younger-Onset N = 365 | Elderly-Onset N = 82 | Crude OR (95% CI) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| History of malignancy | ||||||

| 345 | 95.0% | 57 | 70.4% | r (1) | |

| 18 | 5.0% | 24 | 29.6% | 8.1 (4.1–15.8) | ≤0.001 |

| Number of malignancies | ||||||

| 18 | 5.0% | 17 | 21% | 5.7 (2.8–11.7) | ≤0.001 |

| 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 7.4% | - | ≤0.001 |

| 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.2% | - | 0.144 |

| Treatment of malignancy | ||||||

| 6 | 1.7% | 4 | 5.0% | 4.0 (1.1–14.7) | 0.035 |

| 14 | 3.9% | 19 | 23.8% | 8.2 (3.9–17.3) | ≤0.001 |

| 4 | 1.1% | 4 | 5.0% | 6.0 (1.4–24.9) | 0.013 |

| 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 2.5% | - | 0.021 |

| Duration of malignancy before Y median (min–max) | 3.3 (0–26) | 4.17 (0.08–20) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.907 | ||

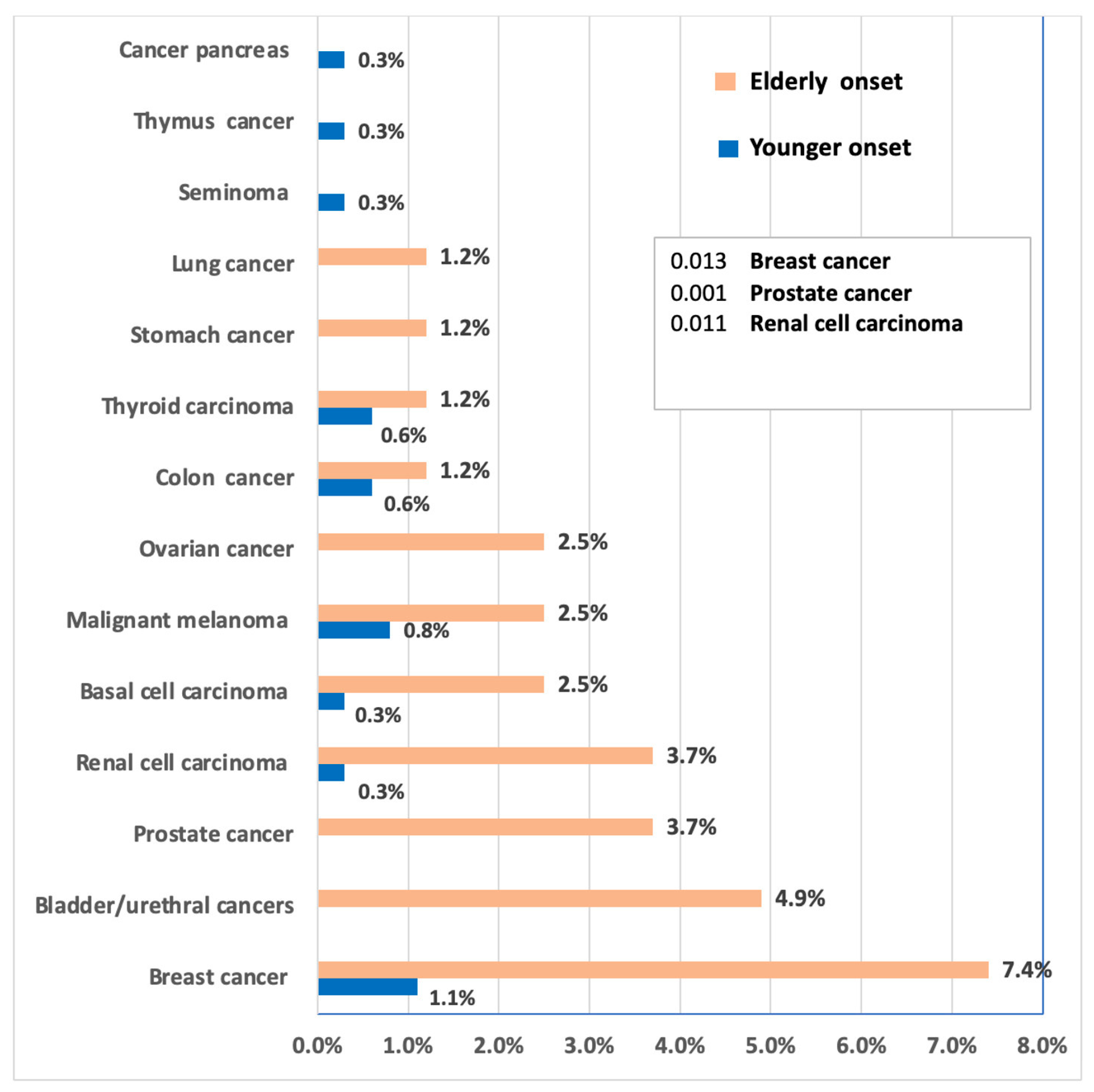

| Tumor Type | <65 n (%) | ≥65 n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For females (N = 174) | ||||

| No malignancy | 119 (91.5) | 33 (75.0) | Reference | — |

| Breast cancer | 4 (3.1) | 6 (13.6) | 5.41 (1.43–20.4) | 0.011 |

| Ovarian cancer | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.5) | 9.67 (0.45–208.3) | 0.048 |

| Other tumors | 7 (5.4) | 3 (6.8) | 1.55 (0.37–6.50) | 0.54 |

| For males (N = 270) | ||||

| No malignancy | 226 (97.0) | 24 (64.9) | Reference | — |

| Prostate cancer | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.1) | 29.3 (1.45–593) | 0.006 |

| Other tumors | 7 (3.0) | 10 (27.0) | 13.4 (4.7–38.1) | <0.001 |

| For all patients | ||||

| No malignancy | 345 (95.0) | 57 (70.4) | Reference | — |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 1 (0.3) | 3 (3.7) | 18.2 (1.85–179) | 0.013 |

| Bladder/urethral | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.9) | 55.6 (2.9–1056) | 0.001 |

| Malignant melanoma | 3 (0.8) | 2 (2.5) | 4.03 (0.67–24.1) | 0.12 |

| Colon cancer | 2 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | 3.03 (0.27–33.6) | 0.36 |

| Lung cancer | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 14.5 (0.57–368) | 0.09 |

| Younger-Onset N = 365 | p Value | Elderly-Onset N = 82 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Malignancy N (%) | Positive Malignancy N (%) | Negative Malignancy N (%) | Positive Malignancy N (%) | |||

| Age: median (min–max) | 47 (23–63) | 53.5 (35–61) | 0.010 | 69 (65–84) | 67.5 (65–80) | 0.427 |

| Sex | ||||||

| 119 (34.5) | 11 (61.1) | 0.022 | 33 (57.9) | 11 (45.8) | 0.320 |

| Smoking: | ||||||

| 138 (52.1) | 10 (76.9) | 0.240 | 17 (43.6) | 8 (50) | 0.892 |

| 64 (24.2) | 1 (7.7) | 20 (51.3) | 7 (43.8) | ||

| 63 (23.8) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (5.1) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| HTN | 67 (19.5) | 4 (22.2) | 0.762 | 40 (75.5) | 18 (75) | 0.965 |

| DM | 29 (8.5) | 1 (5.6) | 1 | 15 (28.8) | 8 (34.8) | 0.607 |

| CAD | 5 (1.4) | 1 (5.6) | 0.265 | 3 (5.3) | 5 (20.8) | 0.046 |

| Hypothyroidism | 10 (2.9) | 1 (5.6) | 0.433 | 4 (7.0) | 2 (8.3) | 1 |

| OSA | 10 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | - |

| COPD | 6 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 1 | 5 (8.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.664 |

| BA | 27 (7.8) | 1 (5.6) | 1 | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Leading symptoms | ||||||

| 68 (19.9) | 11 (61.1) | 0 | 11 (19.6) | 9 (37.5) | 0.091 |

| 135 (39.5) | 2 (11.1) | 0.016 | 17 (30.4) | 5 (20.8) | 0.382 |

| 70 (20.5) | 0 (0) | 0.030 | 30 (53.6) | 10 (41.7) | 0.329 |

| 43 (12.6) | 2 (11.1) | 1 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.513 |

| 47 (13.7) | 2 (11.1) | 1 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.513 |

| 9 (2.6) | 1 (5.6) | 0.405 | 2 (3.6) | 1 (4.2) | 1 |

| 8 (2.3) | 0 | 0.967 | - | - | |

| 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0.405 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 0.510 |

| 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0.270 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0.270 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 (0.9) | 0 | 0.528 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 (0.9) | 0 | 0.528 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0.270 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0.270 | 0 | 0 | |

| Diagnostic methods | ||||||

| 254 (73.6) | 11 (61.1) | 0.277 | 32 (56.1) | 18 (75) | 0.111 |

| 43 (12.5) | 1 (5.6) | 0.709 | 2 (3.5) | 0 | 1 |

| 69 (20) | 2 (11.1) | 0.544 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 |

| 141 (40.9) | 5 (27.8) | 0.269 | 18 (31.6) | 3 (12.5) | 0.074 |

| 30 (8.7) | 4 (22.2) | 0.076 | 10 (17.5) | 1 (4.2) | 0.160 |

| 2 (0.6) | 1 (5.6) | 0.142 | 2 (3.5) | 2 (8.3) | 0.578 |

| 2 (0.6) | 1 (5.6) | 0.142 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 |

| 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.507 |

| Lung function parameters | ||||||

| 3.2 (0.4–5.8) | 3 (1.4–5.1) | 0.318 | 2.2 (0.7–4.3) | 2.4 (1.1–4.5) | 0.169 |

| 90 (4.2–138) | 96.5 (48–134) | 0.080 | 86 (27–139) | 90.5 (47–138) | 0.422 |

| 3.8 (0.4–89) | 3.5 (1.6–6) | 0.117 | 2.6 (0.9–4.9) | 3 (1.3–4.7) | 0.306 |

| 90 (12–139) | 89.5 (45–135) | 0.392 | 82.5 (29–123) | 84.5 (1.9–118) | 0.513 |

| 77 (26–132) | 82 (40–92) | 0.827 | 58.5 (10–108) | 74 (18–95) | 0.324 |

| CT chest morphological signs | ||||||

| 326 (94.6) | 17 (94.4) | 1 | 51 (89.5) | 21 (87.5) | 1 |

| 214 (62.4) | 6 (33.3) | 0.014 | 36 (63.2) | 9 (37.5) | 0.034 |

| Radiological staging according to Scadding | ||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0.102 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (4.3) | 0.254 |

| 134 (39) | 12 (66.7) | 23 (40.4) | 14 (60.9) | ||

| 187 (54.4) | 5 (27.8) | 21 (36.8) | 5 (21.7) | ||

| 18 (5.2) | 1 (5.6) | 7 (12.3) | 3 (13) | ||

| 5 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (8.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Treatment after MDD | 125 (36.4) | 2 (11.1) | 0.028 | 23 (41.1) | 8 (33.3) | 0.515 |

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 1-year increase) | 1.08 | 1.04–1.12 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.33 | 0.58–3.04 | 0.50 |

| Diabetes and/or hypertension | 1.55 | 0.61–3.89 | 0.36 |

| Smoking (ever vs. never) | 0.58 | 0.25–1.36 | 0.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Polish Respiratory Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ehab, A.; Kempa, A.T.; Shalabi, A.; Elkateb, N.; Farrag, N.S.; Abdelwahab, H.W. Exploring the Risk: Investigating the Association Between Elderly-Onset Sarcoidosis (EOS) and Malignancy. Adv. Respir. Med. 2026, 94, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010003

Ehab A, Kempa AT, Shalabi A, Elkateb N, Farrag NS, Abdelwahab HW. Exploring the Risk: Investigating the Association Between Elderly-Onset Sarcoidosis (EOS) and Malignancy. Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 2026; 94(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleEhab, Ahmed, Axel T. Kempa, Ahmad Shalabi, Noha Elkateb, Nesrine Saad Farrag, and Heba Wagih Abdelwahab. 2026. "Exploring the Risk: Investigating the Association Between Elderly-Onset Sarcoidosis (EOS) and Malignancy" Advances in Respiratory Medicine 94, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010003

APA StyleEhab, A., Kempa, A. T., Shalabi, A., Elkateb, N., Farrag, N. S., & Abdelwahab, H. W. (2026). Exploring the Risk: Investigating the Association Between Elderly-Onset Sarcoidosis (EOS) and Malignancy. Advances in Respiratory Medicine, 94(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm94010003