Prevalence of Urinary Tract Cancer in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Data from the Vercelli Registry

Highlights

- A significantly higher prevalence of urinary tract cancer was observed in male patients with moderate-to-severe OSA (34%), compared to females (p < 0.001).

- Patients with genitourinary cancers showed distinct clinical features: better respiratory function, higher C-PAP adherence, and cardiovascular comorbidity, especially hypertension.

- These findings suggest a potential pathophysiological link between OSA-related intermittent hypoxia and genitourinary carcinogenesis, possibly mediated by HIF-1α/2α and VEGF pathways.

- Stratifying cancer risk by OSA phenotype and gender may improve early detection strategies and support the role of PAP therapy in mitigating oncological vulnerability.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection and Procedures

2.3.1. Polysomnographic Assessment

2.3.2. Pulmonary Function Testing

2.3.3. Cancer Diagnosis Ascertainment

2.3.4. Clinical and Demographic Data

2.4. Variables and Definitions

2.4.1. Primary Outcome Variable

- (i)

- Urinary tract cancer (X1): Malignancies classified according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes [25]: C61 (prostate), C67 (bladder), and C64 (kidney);

- (ii)

- Non-urinary tract cancer (X0): All other malignancies, including but not limited to breast, colorectal, lung, laryngeal, skin, intracranial, hematologic, and parotid cancers;

- (iii)

- Multiple primary cancers: Patients with malignancies affecting more than one anatomical site were classified as having multiple primary cancers and were categorized according to the presence or absence of urinary tract involvement.

2.4.2. Exposure Variables

- (i)

- OSA Severity: OSA was classified according to the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) following American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines [22].

- (ii)

- AHI: The number of apneas and hypopneas per h of sleep, calculated from overnight polysomnography according to AASM scoring criteria.

- −

- Mild OSA: AHI 5–14.9 events/h

- −

- Moderate OSA: AHI 15–29.9 events/h

- −

- Severe OSA: AHI ≥ 30 events/h

- (iii)

- ODI: The number of oxygen desaturation events (≥3% decrease from baseline SpO2) per h of sleep.

- (iv)

- t90: The percentage of total sleep time during which oxygen saturation was below 90%, expressed as a percentage.

- (v)

- Mean SpO2: The average oxygen saturation throughout the entire sleep period, expressed as a percentage.

2.4.3. Demographic and Anthropometric Variables

- −

- Age: Age in years at the time of OSA diagnosis.

- −

- Sex: Biological sex classified as male or female.

- −

- Body mass index (BMI): Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). BMI categories were defined according to World Health Organization criteria [26]:

- Normal weight: BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2

- Overweight: BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2

- Obesity class I: BMI 30.0–34.9 kg/m2

- Obesity class II: BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m2

- Obesity class III: BMI ≥ 40.0 kg/m2

2.4.4. Lifestyle and Risk Factors

- Current smoker: Active tobacco use at the time of OSA diagnosis;

- Former smoker: History of tobacco use (≥100 lifetime cigarettes) but not currently smoking;

- Never smoker: No history of tobacco uses or <100 lifetime cigarettes.

2.4.5. Comorbidities

- −

- Cardiovascular disease: Presence of one or more of the following conditions documented in the medical record according to standard diagnostic criteria [32]: hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or hypercholesterolemia.

- −

- Hypertension: Documented clinical diagnosis of arterial hypertension in the medical record or current use of antihypertensive medications at the time of OSA diagnosis.

- −

- Allergy: Documented history of allergic conditions including allergic rhinitis, asthma, atopic dermatitis, or drug/food allergies.

2.4.6. Respiratory Function Variables

- −

- FEV1: The volume of air exhaled in the first second of forced expiration, measured in liters per second (L/s) and expressed as both absolute values and percentage of predicted values based on age, sex, and height.

- −

- FVC: The total volume of air exhaled during forced expiration, measured in liters per second (L/s) and expressed as both absolute values and percentage of predicted values.

- −

2.4.7. Treatment Variables

- −

- C-PAP therapy: Use of C-PAP or other positive airway pressure devices for treatment of OSA, documented in the medical record;

- −

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.5.2. Comparative Analysis

2.5.3. Effect Size Interpretation

2.5.4. Multivariate Analysis

- (i)

- Factorial analysis of mixed data (FAMD): FAMD was used to analyze the heterogeneous clinical dataset containing both continuous variables (e.g., AHI, ODI, FEV1, FVC) and categorical variables (e.g., cancer type, C-PAP compliance, hypertension). FAMD is an extension of principal component analysis (PCA) that can handle mixed data types simultaneously. The analysis was performed using the FAMD function from the FactoMineR package.

- (ii)

- Dimension retention: A scree plot was generated to visualize the percentage of variance explained by each dimension. The first three dimensions were retained for interpretation, as they collectively explained 46.43% of the total variance (Dimension 1: 22.20%, Dimension 2: 14.13%, Dimension 3: 10.11%).

- (iii)

- Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA): Following FAMD, MCA was performed to further explore associations among categorical variables and identify patterns in the data structure.

- (iv)

- Hierarchical clustering: Hierarchical clustering was performed on the FAMD dimensions to identify homogeneous subgroups of patients with similar clinical profiles. The clustering algorithm used Ward’s method with Euclidean distance. A dendrogram was constructed to visualize the hierarchical structure, and the optimal number of clusters was determined by visual inspection of the dendrogram and evaluation of cluster separation in the factor map. The resulting two-cluster solution was validated by examining the distribution of key clinical variables across clusters.

2.6. Bias

2.7. Study Size

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort

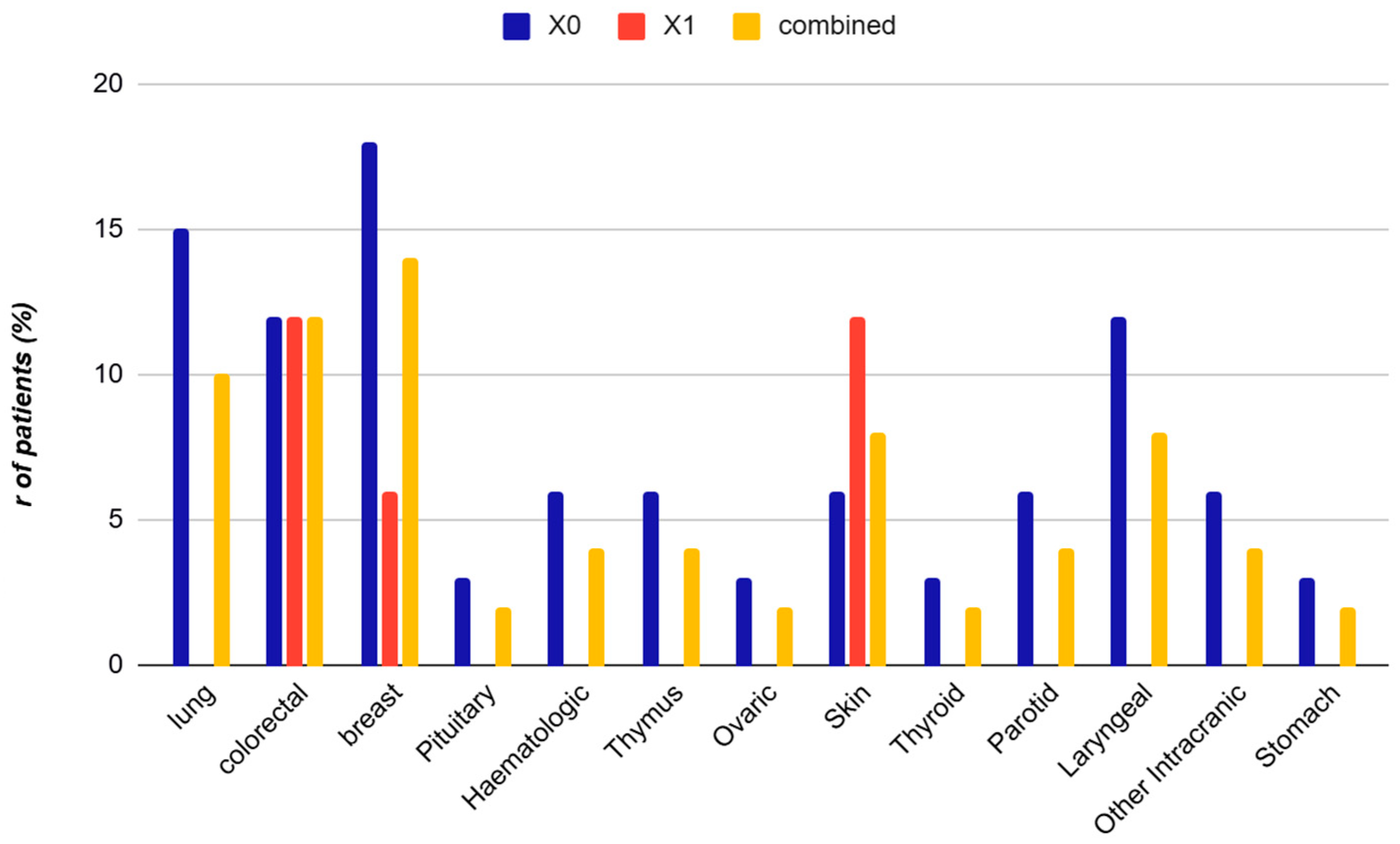

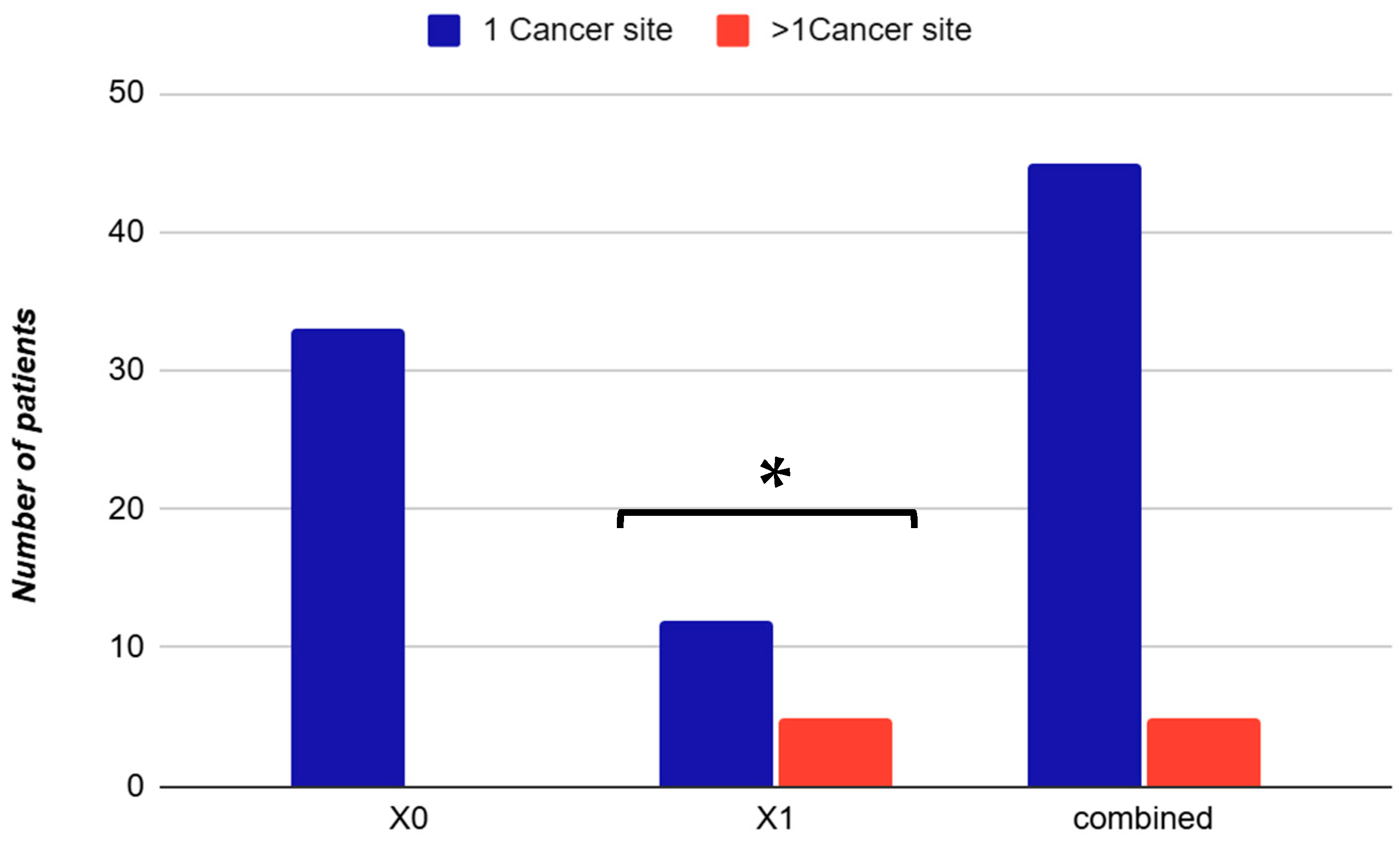

3.2. Cancer Type Distribution

3.3. Multivariate Analysis: Factorial Analysis of Mixed Data and Hierarchical Clustering Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gleeson, M.; McNicholas, W.T. Bidirectional relationships of comorbidity with obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsignore, M.R.; Baiamonte, P.; Mazzuca, E.; Castrogiovanni, A.; Marrone, O. Obstructive sleep apnea and comorbidities: A dangerous liaison. Respir. Med. 2019, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataka, A.; Bonsignore, M.R.; Ryan, S.; Riha, R.L.; Pepin, J.L.; Schiza, S.; Basoglu, O.K.; Sliwinski, P.; Ludka, O.; Steiropoulos, P.; et al. OSA and cancer prevalence—Data from the ESADA study. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1900091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffler, K.A.; Heeley, E.; Freed, R.; Anderson, C.S.; Brockway, B.; Corbett, A.; Chang, C.L.; Douglas, J.A.; Ferrier, K.; Graham, N.; et al. Effect of Obstructive Sleep Apnea treatment on renal function in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholl, D.D.M.; Ahmed, S.B.; Loewen, A.H.S.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Sola, D.Y.; Beecroft, J.M.; Turin, T.C.; Hanly, P.J. Declining kidney function increases the prevalence of sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxia. Chest 2012, 141, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrone, O.; Cibella, F.; Pépin, J.-L.; Verbraecken, J.; Saaresranta, T.; Kvamme, J.A.; Grote, L.; Basoglu, O.K.; Lombardi, C.; McNicholas, W.; et al. Estimated glomerural filtration rate (Egfr) changes after obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treatment by positive airway pressure: Data from the European Sleep Apnea Database (ESADA). Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, PA4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochetti, P.; Azzolina, D.; Ragnoli, B.; Tillio, P.A.; Cantaluppi, V.; Malerba, M. Interrelationship among Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Renal Function and Survival: A cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrone, O.; Cibella, F.; Pépin, J.-L.; Grote, L.; Verbraecken, J.; Saaresranta, T.; Kvamme, J.A.; Basoglu, O.K.; Lombardi, C.; McNicholas, W.T.; et al. Fixed But Not Autoadjusting Positive Airway Pressure Attenuates the Time-Dipendent Decline in Glomerular Filatration Rate in Patients with OSA. Chest 2018, 154, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, A.; Tavassoli, A. Hypoxia-inducible transcription factors: Architects of tumorigenesis and targets for anticancer drug discovery. Transcription 2024, 16, 86–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.; Pranoto Hallis, S.; Kwak, M.-K. Hypoxia, oxidative stress, and the interplay of HIFs and NRF2 signaling in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavalle, S.; Masiello, E.; Iannella, G.; Magliulo, G.; Pace, A.; Lechien, J.R.; Calvo-Henriquez, C.; Cocuzza, S.; Parisi, F.M.; Favier, V.; et al. Unraveling the Complexities of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Biomarkers in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Life 2024, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Teske, J.A.; Mashaqi, S.; Combs, D. Obstructive sleep apnea, the NLRP3 inflammasome and the potential effects of incretin therapies. Front. Sleep 2025, 3, 1524593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.J.; LeRoith, D. Obesity and diabetes: The increased risk of cancer and cancer-related mortality. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zeng, L. The Pathophysiological Relationship and Treatment Progress of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, Obesity, and Metabolic Syndrome. Explor. Res. Hypothesis Med. 2025, 10, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppard, P.E.; Young, T.; Barnet, J.H.; Palta, M.; Hagen, E.W.; Hla, K.M. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nusair, M.; Al-Nusair, J.; Obeidat, O.; Alagha, Z.; Wright, T.; Al-Momani, Z.; Alnabahneh, N.; Pacioles, T.; Mahdi, A.; MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC; et al. Unmasking the link between sleep apnea and lung cancer risk: A retrospective propensity-matched cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrogiovanni, A.; Modica, D.M.; Amata, M.; Bonsignore, M.R. Obstructive sleep apnea and cancer: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical aspects. Minerva Respir. Med. 2024, 63, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.K.J.; Teo, Y.H.; Tan, N.K.W.; Yap, D.W.T.; Sundar, R.; Lee, C.H.; See, A.; Toh, S.T. Association of obstructive sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxemia with all-cancer incidence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yao, Q. Obstructive sleep apnea and incidence of malignant tumors: A metaanalysis. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, T.; Gudmundsson, E.F. Obstructive sleep apnea and cancer—A nationwide epidemiological survey. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48 (Suppl. 60), PA341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, V.K.; Auckley, D.H.; Chowdhuri, S.; Kuhlmann, D.C.; Mehra, R.; Ramar, K.; Harrod, C.G. Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.B.; Brooks, R.; Gamaldo, C.; Harding, S.M.; Lloyd, R.M.; Quan, S.F.; Troester, M.T.; Vaughn, B.V. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2.4; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, B.L.; Steenbruggen, I.; Miller, M.R.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Cooper, B.G.; Hall, G.L.; Hallstrand, T.S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; McCarthy, K.; McCormack, M.C.; et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society technical statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic; WHO Technical Report Series 894; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peppard, P.E.; Young, T.; Palta, M.; Dempsey, J.; Skatrud, J. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA 2000, 284, 3015–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, T.; Peppard, P.E.; Gottlieb, D.J. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: A population health perspective. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 1217–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegal, K.M.; Kit, B.K.; Orpana, H.; Graubard, B.I. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013, 309, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskaran, K.; Douglas, I.; Forbes, H.; dos-Santos-Silva, I.; Leon, D.A.; Smeeth, L. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: A population-based cohort study of 5.24 million UK adults. Lancet 2014, 384, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, DC, USA, 2014.

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; McEvoy, J.W.; et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2019, 140, e596–e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Crapo, R.; Enright, P.; Van Der Grinten, C.P.M.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.M.; Zheng, J.; et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: The global lung function 2012 equations. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kribbs, N.B.; Pack, A.I.; Kline, L.R.; Smith, P.L.; Schwartz, A.R.; Schubert, N.M.; Redline, S.; Henry, J.N.; Getsy, J.E.; Dinges, D.F. Objective measurement of patterns of nasal CPAP use by patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993, 147, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, T.E.; Grunstein, R.R. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy: The challenge to effective treatment. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using effect size—Or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozal, D.; Ham, S.A.; Mokhlesi, B. Sleep apnea and cancer: Analysis of a nationwide population sample. Sleep 2016, 39, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almendros, I.; Gozal, D. Intermittent hypoxia and cancer: Elucidating the links and the therapeutic implications. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 618–620. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, A.J.Y.; Tan, B.K.J.; Teo, Y.H.; Tan, N.K.W.; Sia, C.-H.; Ong, T.H.; Leow, L.C.; See, A.; Toh, S.T. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Lung CancerA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Am. Thorac. Soc. 2022, 19, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Duan, R.; Li, Q.; Mo, R.; Zheng, P.; Feng, T. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and risk of lung cancer: Findings from a collection of cohort studies and Mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1346809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Yue, H. Advances in immunology of obstructive sleep apnea: Mechanistic insights, clinical impact, and therapeutic perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1654450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborg, S.; Cronin-Fenton, D.; Jensen, M.-B.R.; Ahern, T.P.; Ewertz, M.; Borgquist, S. Obesity and Risk of Recurrence in Patients with Breast Cancer Treated with Aromatase Inhibitors. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2337780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, B.S.Y.; Yap, D.W.T.; Tan, N.K.W.; Tan, B.K.J.; Teo, Y.N.; Lee, A.; See, A.; Ho, H.S.S.; Teoh, J.Y.-C.; Chen, K.; et al. The Association of Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Urological Cancer Incidence and Mortality—A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 10, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 2012, 148, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, E.B.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxic control of metastasis. Science 2016, 352, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krock, B.L.; Skuli, N.; Simon, M.C. Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis: Good and evil. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaelin, W.G., Jr. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and clear cell renal carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13 Pt 2, 680s–684s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-de-la-Torre, M.; Cubillos, C.; Veatch, O.J.; Garcia-Rio, F.; Gozal, D.; Martinez-Garcia, M.A. Potential Pathophysiological Pathways in the Complex Relationships between OSA and Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsignore, M.R.; ESADA Study Group. Adaptive responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia: Contributions from the European Sleep Apnoea Database (ESADA) Cohort. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 5467–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzer, R.; Vat, S.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Marti-Soler, H.; Andries, D.; Tobback, N.; Mooser, V.; Preisig, M.; Malhotra, A.; Waeber, G.; et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: The HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, L. Oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea and intermittent hypoxia—Revisited—The bad ugly and good: Implications to the heart and brain. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 20, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.; Taylor, C.T.; McNicholas, W.T. Selective activation of inflammatory pathways by intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Circulation 2005, 112, 2660–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Hu, Y.; Xu, F.; Feng, X. A review of obstructive sleep apnea and lung cancer: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic options. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1374236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, E.; Zakei, A.; Bratty, A.J.; Khazaie, H. The Relationship Between Slow Wave Sleep and Blood Oxygen Saturation Among Patients with Apnea: Retrospective Study. Sleep Med. Res. 2023, 14, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almendros, I.; Montserrat, J.M.; Ramírez, J.; Torres, M.; Duran-Cantolla, J.; Navajas, D.; Farré, R. Intermittent hypoxia enhances cancer progression in a mouse model of sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, R.A.; Harris, I.S.; Mak, T.W. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivali, N.; De Giacomi, F. Does CPAP increase or protect against cancer risk in OSA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2025, 29, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Garcia, M.A.; Campos-Rodriguez, F.; Farré, R. Cancer and obstructive sleep apnea: Current evidence and future perspectives. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Ning, P.; Li, Q.; Wu, S. Cancer and obstructive sleep apnea: An updated meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e28930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaie, H.; Aghazadeh, M.; Zakiei, A.; Maazinezhad, S.; Tavallaie, A.; Moghbel, B.; Azarian, M.; Mozafari, F.; Norouzi, E.; Sweetman, A.; et al. Co-morbid Insomnia and Sleep Apnea (COMISA) in a large sample of Iranian: Prevalence and associations in a sleep clinic population. Sleep Breath. 2024, 28, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozal, D.; Almendros, I. The impact of CPAP therapy on cancer risk in OSA patients: Myth or reality? Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 62, 101589. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Non-Urinary (X0) (n = 33) | Urinary (X1) (n = 17) | Combined (n = 50) | Effect Size (Cohen’s d/h) | OR (CI 95%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 20 (61%) | 15 (88%) | 35 (70%) | h = 0.66 | 0.21 [0.04; 1.05] | 0.043 * |

| Age (years) | 68.0 ± 7.0 | 65.0 ± 3.0 | 67.0 ± 7.0 | d = −0.50 | 0.94 [0.87; 1.02] | 0.107 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 3.0 | 29.0 ± 4.0 | 29.0 ± 4.0 | d = 0.00 | 1.01 [0.85; 1.20] | 0.958 |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | 25 (76%) | 12 (73%) | 37 (74%) | h = −0.12 | 0.83 [0.16; 4.40] | 0.830 |

| Allergy, n (%) | 11 (32%) | 5 (30%) | 16 (32%) | h = −0.09 | 0.93 [0.18; 4.90] | 0.900 |

| CV Disease, n (%) | 28 (85%) | 17 (100%) | 45 (90%) | h = 0.80 | NE | 0.300 |

| C-PAP treatment, n (%) | 25 (76%) | 13 (77%) | 38 (76%) | h = 0.02 | 0.95 [0.20; 4.63] | 0.900 |

| C-PAP compliance, n (%) | 20 (61%) | 16 (94%) | 36 (72%) | h = 0.87 | 8.98 [1.50; 236] | 0.018 * |

| AHI (events/h) | 37.0 ± 30.0 | 24.0 ± 15.0 | 32.0 ± 26.0 | d = −0.50 | 0.97 [0.94; 1.01] | 0.200 |

| Mean SpO2 (%) | 94.0 ± 3.0 | 93.0 ± 2.0 | 93.0 ± 2.0 | d = −0.37 | 0.81 [0.56; 1.17] | 0.300 |

| FEV1 (L/s) | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | d = 1.38 | 4.22 [0.88; 20.1] | 0.010 ** |

| FEV1 (%) | 84.0 ± 21.0 | 101.0 ± 9.0 | 88.0 ± 21.0 | d = 0.95 | 1.07 [0.97; 1.18] | 0.100 |

| FVC (L/s) | 2.8 ± 0.9 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | d = 1.61 | 4.05 [0.96; 17.1] | 0.006 ** |

| FVC (%) | 84.0 ± 18.0 | 100.0 ± 8.0 | 87.0 ± 17.0 | d = 1.04 | 1.08 [0.98; 1.18] | 0.090 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.81 ± 0.11 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | d = 0.00 | 0.96 [0.00; 1774] | 0.440 |

| ODI | 33.0 ± 26.0 | 22.0 ± 14.0 | 29.0 ± 23.0 | d = −0.48 | 0.97 [0.93; 1.02] | 0.300 |

| t90 (%) | 18.0 ± 25.0 | 6.0 ± 10.0 | 14.0 ± 21.0 | d = −0.57 | 0.95 [0.88; 1.03] | 0.100 |

| Mean SpO2 (%) | 94.0 ± 3.0 | 93.0 ± 2.0 | 93.0 ± 2.0 | d = −0.37 | 0.81 [0.56; 1.17] | 0.300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Polish Respiratory Society. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ragnoli, B.; Pochetti, P.; Chiazza, F.; Bertelegni, C.; Azzolina, D.; Malerba, M. Prevalence of Urinary Tract Cancer in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Data from the Vercelli Registry. Adv. Respir. Med. 2025, 93, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060054

Ragnoli B, Pochetti P, Chiazza F, Bertelegni C, Azzolina D, Malerba M. Prevalence of Urinary Tract Cancer in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Data from the Vercelli Registry. Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 2025; 93(6):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060054

Chicago/Turabian StyleRagnoli, Beatrice, Patrizia Pochetti, Fausto Chiazza, Carlotta Bertelegni, Danila Azzolina, and Mario Malerba. 2025. "Prevalence of Urinary Tract Cancer in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Data from the Vercelli Registry" Advances in Respiratory Medicine 93, no. 6: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060054

APA StyleRagnoli, B., Pochetti, P., Chiazza, F., Bertelegni, C., Azzolina, D., & Malerba, M. (2025). Prevalence of Urinary Tract Cancer in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Data from the Vercelli Registry. Advances in Respiratory Medicine, 93(6), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arm93060054