Abstract

Migraine is a common disabling primary headache disorder with significant personal and socio-economic impacts. A combination of medication and non-pharmacological therapies is essential for migraine management. Outpatient multidisciplinary headache therapy has not yet been evaluated in Switzerland. This study evaluates the effectiveness of the headache management program at Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, in improving headache-related disability in migraine patients. This open-label pilot study used prospectively assessed routine data from our headache registry. Participants aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of migraine, confirmed by a headache specialist, were included. The program consisted of seven weekly sessions, each with a 50 min educational lecture and a 30 min progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) exercise. Primary outcomes were headache-related impact and disability, measured by the Headache Impact Test 6 (HIT-6) and Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS). Secondary outcomes included symptoms of anxiety, measured by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), and symptoms of depression, assessed using the eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8). Data were analysed using paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed rank tests. Significant improvements were observed in HIT-6 scores (pre-program: 65.2; post-program: 61.9; p = 0.012) and MIDAS scores (pre-program: 38; post-program: 27; p = 0.011), while PHQ-8 also showed a statistically significant reduction. Although the GAD-7 scores improved numerically, this change was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that the headache management program may reduce headache burden and disability; however, further research with larger samples is needed to confirm these preliminary results.

1. Introduction

Migraine is a common disabling primary headache disorder with significant personal and socio-economic impacts. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2019, headache disorders are the second most common cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) in Europe. The most frequent headache disorders include migraine, tension-type headache (TTH), and medication overuse headache (MOH). Globally, headache disorders accounted for 46.6 million YLDs, with 88.2% attributed to migraine [1].

Recent advancements in pharmacotherapy have improved migraine management [2]; yet, a substantial proportion of individuals cannot be managed successfully with pharmacological treatments alone. Non-pharmacological treatments for migraine include cognitive behavioural therapy [3], biofeedback, relaxation therapies, mindfulness-based therapies, physiotherapy, aerobic exercise, acupuncture, and educational interventions [4,5]. A combination of medication and behavioural therapies is considered optimal for acute treatment and prophylaxis [6,7].

For individuals with severe and/or refractory migraine, we developed a multidisciplinary outpatient program (headache management program) at Inselspital, Bern University Hospital. This innovative approach, which combines structured group sessions, patient education (PE), and relaxation techniques, involves the headache outpatient clinic and the psychosomatic clinic with its physiotherapy service.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the headache management program in reducing headache-related burden in migraine patients. We hypothesise that the program may meaningfully improve headache-related disability. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate a structured multidisciplinary outpatient headache management program in Switzerland that combines patient education and physiotherapy-led progressive muscle relaxation. This context-specific approach addresses a gap in the current literature and offers a practical low-resource intervention for migraine care.

2. Materials and Methods

This open-label single-arm pilot study had ethics approval from the cantonal ethics committee as part of our headache registry (project ID: 2021-01628) and used prospectively assessed routine data. All patients gave written informed consent.

To be included, patients had to be at least 18 years old and seen in the outpatient headache centre before the start of the program. Patients were required to have episodic or chronic migraine according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3 [8]. The diagnosis had to be made by a headache specialist, who recommended inclusion in the headache management program as part of routine clinical care.

In this structured group program, up to 10 participants meet once per week for seven weeks. Each appointment builds on the previous with respect to the content and training (Table 1) and consists of (i) 30 min of a physiotherapeutically guided and standardized session of progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) according to Jacobson, followed by (ii) approx. 50 min of education on headaches with a focus on migraine, its comorbidities, risk factors for chronification, and treatment, which a psychologist or headache specialist moderates depending on the topic (see Supplementary Materials).

Table 1.

Structured headache management program by week.

This pilot study focused on migraine burden and disability; thus, the Headache Impact Test 6 (HIT-6) and Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) were used as primary outcome parameters. HIT-6 is a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure that assesses the adverse effects of headaches on normal daily activity. It comprises six questions, each rated on a scale from 6 to 13, with the total score ranging from 36 to 78. Higher scores indicate greater impairment [9,10,11,12,13]. MIDAS measures headache-related disability in three domains during the three previous months: (school)work, household and family, social, and leisure activities. The scale consists of five questions, with responses given in days and summed to obtain a score. Scores range from 0 to over 21, with higher scores indicating greater disability [14,15]. Secondary outcome parameters are the two main comorbidities of migraine: anxiety and depression. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) is a screening questionnaire for detecting generalised anxiety in a primary care setting and is a validated tool in patients with migraine. It consists of seven questions that assess the frequency of symptoms over the past two weeks. Responses are rated on a scale from 0 to 3, with the total score ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety [16,17]. The eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8) is a tool for screening and measuring the severity of depression. It is a validated tool in patients with migraine. It comprises eight questions that assess the frequency of symptoms over the past two weeks. Responses are rated on a scale from 0 to 3, with the total score ranging from 0 to 24. Higher scores indicate more severe depression [18,19,20]. The questionnaires were filled prospectively, and all those available after five program cycles up to September 2022 were considered for analysis in this pilot study.

The primary endpoints were the difference in HIT-6 and MIDAS between pre- and post-program, and the secondary endpoints were the difference in PHQ-8 and GAD-7 between pre- and post-program.

As this was an exploratory pilot study, no formal sample size calculation was performed. The aim was to assess the feasibility and generate preliminary data to inform the design of a future randomised controlled trial.

Statistical Analyses

Pseudonymised data were checked for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. We used descriptive statistics. Counts are given in percentages, and continuous variables are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or median, as appropriate. For comparisons of baseline scores to the scores after completion of the headache management program, the paired t-test and Wilcoxon signed rank test were used as appropriate. Box plots were created to visualize the distribution of the scores. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29.0 was used for the statistical analyses.

We considered a p value of <0.05 as statistically significant and a ≥2.3-point decline in HIT-6 and a ≥4.5-point decline in MIDAS as clinically relevant based on existing data from the literature [21,22,23].

The data were managed and validated through a structured process within our headache registry, and a member of the research team checked it for accuracy and completeness.

3. Results

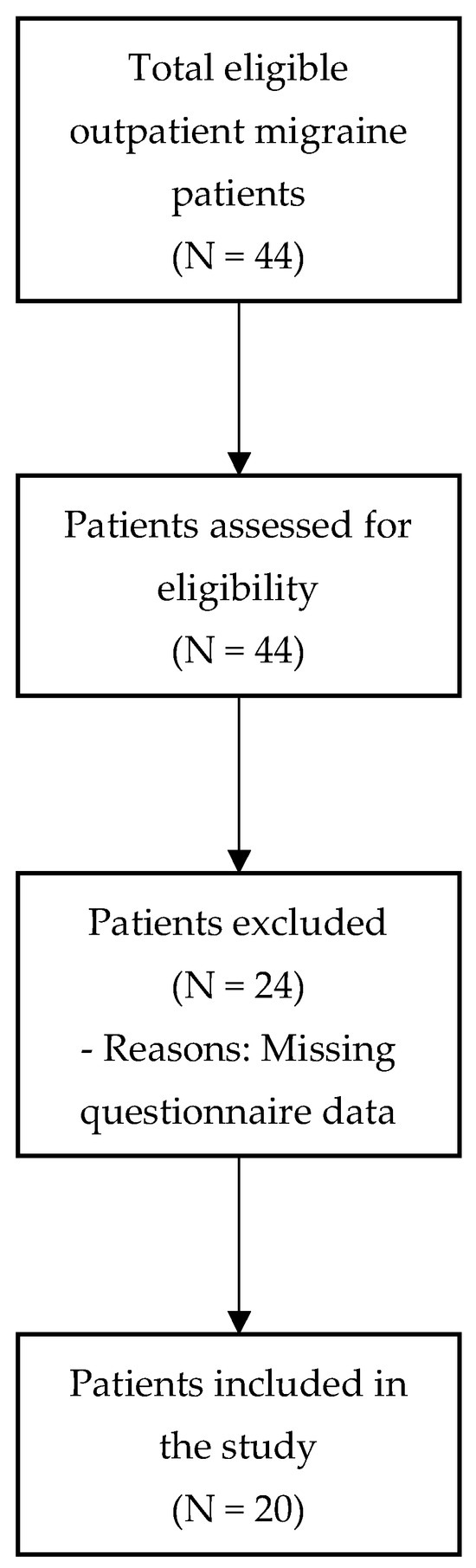

As part of this pilot study, the complete data sets of 20 program participants were included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection.

All patients were women between the ages of 18 and 64 years (M = 37.3, SD = 12.8). Seven patients had chronic migraine, three with aura and four without. Eleven patients had episodic migraine, two with aura and nine without. One patient had a diagnosis of TTH, and another had no diagnostic entry.

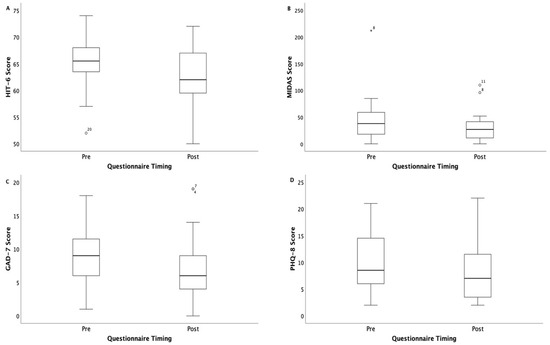

Significant improvements were observed in the HIT-6 scores (mean 61.9 [6] vs. 65.2 [4.8] points, p = 0.012) and PHQ-8 scores (8.3 [5.6] vs. 10.4 [5.8], p = 0.007) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in patient-reported outcome scores pre- to post-program (N = 20).

The Wilcoxon signed rank test showed a non-significant improvement in the median GAD-7 score (median 6 [IQR 5] vs. 9 [IQR 6.3], p = 0.134). The MIDAS scores improved significantly as well (27 [IQR 37.8] vs. 38 [IQR 49], p = 0.011) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Decline in questionnaire scores before and after the headache management program. The box plots show the median (P50), interquartile range (Q1 to Q3), whiskers (minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range), and outliers: (A) HIT-6, Headache Impact Test; (B) MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment; (C) GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder; (D) PHQ-8, Patient Health Questionnaire.

4. Discussion

This study contributes novel insights by evaluating a structured outpatient program for migraine management in a Swiss clinical setting. Unlike previous studies, our program integrates physiotherapy-led PMR and educational sessions in a group format, making it both resource-efficient and scalable.

The main finding of our study is the clinically relevant improvement in HIT-6 and MIDAS scores after completion of the headache management program. Notably, other authors suggest a cut-off for the clinical relevance of a ≥4.5-point decrease in HIT-6 [24,25], but it needs to be stressed that we used the between-group minimally important difference (MID) instead of the between-individuals MID. The PHQ-8 scores declined by 2.1 points and the GAD-7 by 3 points from mild to moderate baseline values. Although both are small effect sizes, there is some improvement in these important comorbidities. The reduction in PHQ-8 scores was statistically significant (p = 0.007), indicating that the observed change is unlikely to be due to chance.

The small sample size and lack of a priori power calculation limit the generalizability of our findings. However, as a pilot study, our results provide valuable initial evidence and support the feasibility of the intervention. A future study with a larger and more diverse sample and formal power analysis is warranted.

These results support the hypothesis that the headache management program, despite its low utilization of resources, may help to improve headache-related disability. The program is not time-consuming, can be conducted in an outpatient setting, and runs for only seven weeks with one lecture a week in the evening. This structure makes it a feasible addition to standard migraine care. Our results are in line with previous research. Bromberg et al. found that a web-based educational intervention incorporating the principles of cognitive behavioural therapy and self-management led to significant improvements in migraine-related coping, depression, and stress, compared to treatment as usual [26]. The systematic review by Perlini et al. found that psychological interventions for chronic headaches, on their own or as part of a multidisciplinary treatment regime, are feasible, well-tolerated, and effective treatment approaches [27]. Furthermore, according to the systematic review by Kindelan-Calvo et al., there is strong to moderate evidence for the intermediate-term effectiveness of therapeutic PE for migraine [28].

The present study has several strengths. The data were assessed prospectively using validated and reliable measurement tools to ensure the validity and accuracy of the collected data. It also allowed for comparison with the existing headache literature. The questionnaires were quick and easy to fill out. However, although we know from previous research that migraine is two to three times more prevalent in women [29,30], we cannot generalize the results to men and are limited in generalizing to the broader population of women with migraine due to the small sample size of 20 women. No headache days were included in this study because insufficient data were available. However, we think this limitation has a minor impact since we show improvement in migraine-related burden and a reduction in migraine-related disability, which, from patients’ perspective, might be more relevant. In addition, no acute and/or prophylactic medication use was considered, and as such, no isolation of the effects of the headache management program from the effects of drug management took place. Additionally, there was no control group for comparison, a major limitation of this study.

Therefore, further research should include a randomised controlled trial with a larger more heterogeneous sample size and a control group. It should comprise headache days, gathered through a headache diary, as well as acute and prophylactic medication use, so the effects of the headache management program can be isolated from drug management.

5. Conclusions

The preliminary data gathered from this pilot study suggest that the headache management program may improve headache burden and disability in a clinically relevant manner and has the potential to become a valuable addition to standard headache care. However, further research should include a randomised controlled trial with a larger and more heterogeneous sample size and control group to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://neurologie.insel.ch/de/unser-angebot/ambulantes-neurozentrum-anz/sprechstunde-kopfschmerzen/kopfschmerz-management-gruppe, Leaflet: Headache Management Program (last accessed on 10 June 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S., B.R.W., C.J.S., N.B. and O.F.; methodology, R.S., B.R.W., C.J.S., A.S. and D.B.; software, R.S., B.R.W. and C.J.S.; validation, R.S., B.R.W. and C.J.S.; formal analysis, R.S., B.R.W. and C.J.S.; investigation, R.S., B.R.W., C.J.S. and O.F.; resources, R.S., B.R.W., C.J.S., N.B. and O.F.; data curation, R.S., B.R.W. and C.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., B.R.W. and C.J.S.; writing—review and editing, R.S., B.R.W., C.J.S., N.B., O.F., J.G., A.S., K.S. and D.B.; visualization, R.S., B.R.W., C.J.S. and O.F.; supervision, B.R.W., C.J.S., K.S. and D.B.; project administration, R.S., B.R.W., C.J.S., N.B. and O.F.; funding acquisition, B.R.W. and C.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Cantonal Ethics Committee for Research, Bern (KEK Bern) (project ID: 2021-01628, date of approval: 18 November 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all persons involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Outside of this study, (1) C.J.S. reports fees for consulting, advisory boards, presentations, and travel support for/from Novartis, Eli Lilly, TEVA Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Allergan, Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Lundbeck, MindMed, and Grünenthal. He is a part-time-employee at Zynnon. He has received research support from TEVA Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Swiss Heart Foundation, Eye on Vision Foundation, Baasch-Medicus Foundation, German Migraine and Headache Society, and the Visual Snow Syndrome Germany e.V., (2) B.R.W. and K.S. are involved in a project to prevent pain chronification (PrePaC) sponsored by Health Promotion Switzerland. None of these funders had any influence on the design of the study, the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIT-6 | Headache Impact Test 6 |

| MIDAS | Migraine Disability Assessment |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale |

| PHQ-8 | Eight-item Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale |

References

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbanti, P.; Egeo, G.; Proietti, S.; d’Onofrio, F.; Aurilia, C.; Finocchi, C.; Di Clemente, L.; Zucco, M.; Doretti, A.; Messina, S.; et al. Assessing the Long-Term (48-Week) Effectiveness, Safety, and Tolerability of Fremanezumab in Migraine in Real Life: Insights from the Multicenter, Prospective, FRIEND3 Study. Neurol. Ther. 2024, 13, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.-Y.; Sung, H.-K.; Kwon, N.-Y.; Go, H.-Y.; Kim, T.-J.; Shin, S.-M.; Lee, S. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Migraine Headache: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2022, 58, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailani, J.; Burch, R.C.; Robbins, M.S. Board of Directors of the American Headache S. The American Headache Society Consensus Statement: Update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 2021, 61, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropp, P.; Meyer, B.; Dresler, T.; Fritsche, G.; Gaul, C.; Niederberger, U.; Förderreuther, S.; Malzacher, V.; Jürgens, P.T.; Marziniak, M.; et al. Relaxation techniques and behavioural therapy for the treatment of migraine: Guidelines from the German Migraine and Headache Society. Schmerz 2017, 31, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanos, S. Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewirtz, A.; Minen, M. Adherence to Behavioral Therapy for Migraine: Knowledge to Date, Mechanisms for Assessing Adherence, and Methods for Improving Adherence. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2019, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendas-Baum, R.; Yang, M.; Varon, S.F.; Bloudek, L.M.; DeGryse, R.E.; Kosinski, M. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT6) in patients with chronic migraine. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, K.L.; Mars, T.S.; Potter, R.; Patel, S.; Matharu, M.; Underwood, M. Assessing the impact of headaches and the outcomes of treatment: A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Blaisdell, B.; Kwong, J.W.; Bjorner, J.B. The Short-Form Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) was psychometrically equivalent in nine languages. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2004, 57, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinski, M. A six item short form survey for measuring headache impact the HIT6. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Rendas-Baum, R.; Varon, S.F.; Kosinski, M. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) across episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2011, 31, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, W.F. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment MIDAS score in comparison to a diary based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain 2000, 88, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benz, T.; Lehmann, S.; Gantenbein, A.R.; Sandor, P.S.; Stewart, W.F.; Elfering, A.; Aeschlimann, A.G.; Angst, F. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and reliability of the German version of the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, F.; Manea, L.; Trepel, D.; McMillan, D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.G.; Park, S.P. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and GAD-2 in patients with migraine. J. Headache Pain 2015, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Rief, W.; Klaiberg, A.; Braehler, E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2006, 28, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.G.; Park, S.P. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and PHQ-2 in patients with migraine. J. Headache Pain 2015, 16, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, C.; Lee, S.H.; Han, K.M.; Yoon, H.K.; Han, C. Comparison of the Usefulness of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9 for Screening for Major Depressive Disorder: Analysis of Psychiatric Outpatient Data. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeytaux, R.R.; Kaufman, J.S.; Chao, R.; Mann, J.D.; Devellis, R.F. Four methods of estimating the minimal important difference score were compared to establish a clinically significant change in Headache Impact Test. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006, 59, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smelt, A.F.; Assendelft, W.J.; Terwee, C.B.; Ferrari, M.D.; Blom, J.W. What is a clinically relevant change on the HIT-6 questionnaire? An estimation in a primary-care population of migraine patients. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, G.F.; Luedtke, K.; Braun, T. Minimal important change and responsiveness of the Migraine Disability Assessment Score (MIDAS) questionnaire. J. Headache Pain 2021, 22, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, M.; Hassan, A.; Nada, M.A.F.; Mohammed, Z.; Abdel Ghaffar, N.F.; Kedah, H.; Fathy, W.; Magdy, R. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Arabic version of HIT-6 questionnaire in patients with migraine indicated for preventive therapy: A multi-center study. Headache 2024, 64, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houts, C.R.; Wirth, R.J.; McGinley, J.S.; Cady, R.; Lipton, R.B. Determining Thresholds for Meaningful Change for the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) Total and Item-Specific Scores in Chronic Migraine. Headache 2020, 60, 2003–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, J.; Wood, M.E.; Black, R.A.; Surette, D.A.; Zacharoff, K.L.; Chiauzzi, E.J. A randomized trial of a web-based intervention to improve migraine self-management and coping. Headache 2012, 52, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlini, C.; Donisi, V.; Del Piccolo, L. From research to clinical practice: A systematic review of the implementation of psychological interventions for chronic headache in adults. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindelan-Calvo, P.; Gil-Martínez, A.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Pardo-Montero, J.; Muñoz-García, D.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; Touche, R.L. Effectiveness of therapeutic patient education for adults with migraine. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 1619–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetvik, K.G.; MacGregor, E.A. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, T.J.; Stovner, L.J.; Jensen, R.; Uluduz, D.; Katsarava, Z. Lifting The Burden: The Global Campaign against H. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: Findings from GBD2019. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Swiss Federation of Clinical Neuro-Societies. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).