1. Introduction

Personalization, defined by Oxford Languages as the action of designing or producing something to meet someone’s individual requirements, is one of the most important trends in e-commerce today. Its practical importance is underlined by market research conducted by major consultancies. For example, 41% of customers say that personalization is the reason they currently subscribe or plan to subscribe to a particular product or service [

1]. In addition, 71% of consumers expect personalization, and 76% are frustrated when they do not find it [

2]. At the same time, the growing importance of e-commerce in the global economy should not be overlooked. Its share of retail sales is forecast to rise from 17% to 41% by 2027 [

3].

Implementing the human-centered concept in e-commerce requires improving the customer’s user experience (UX). To achieve this goal, it is critical to focus on the user interface (UI)—the appearance and content presented [

4]. This is due to the nature of this channel, where the interaction between business and consumer takes place on websites or in emails. On the one hand, this may seem like a disadvantage because it limits the ability to influence the audience in multiple directions, but on the other hand, it is an advantage because it allows for a focus on optimizing communication through the UI of the e-commerce system. It is worth noting that usability and perceived usefulness can be predictors of the frequency of use of e-commerce solutions [

5], and consequently affect business efficiency.

Typically, UI design involves UX experts identifying trade-offs to satisfy diverse customer needs. A/B testing is often used for this purpose [

6]. However, this approach leads to a situation where a one-size-fits-all layout has to meet the expectations of different users, which contradicts the idea of personalization and individualization of communication. In this case, technical limitations preclude a human-centered approach. An alternative is to use a multi-variant UI, which allows serving different versions of the layout, tailored to specific customer groups [

7]. Such a solution requires, on the one hand, the collection of user behavior information to segment users and analyze their characteristics and, on the other hand, it must allow the design, implementation, and verification of modifications aimed at personalizing the different UI variants. Tailoring of UI variants should be based on feedback resulting from customer choices (similar to A/B testing [

8]), but can be managed by a human expert or result from implemented self-adaptation algorithms. The latter option is discussed further in the paper. The proposed solution combines the concept of human-centered machine learning [

9], which is the processing of information about user behavior to improve their experience in interacting with an information system, with the automation of user interface adaptation, leading to the idea of intelligent user interface (IUI) [

10].

Adaptive user interfaces (AUIs) have been evolving practically since the beginning of computer applications in business in the 1960s [

11]. They can be described as an interface that can change its behavior to suit an individual or a group of individuals [

12]. It is worth noting that

adaptive does not always mean the same thing. At least four different levels of adaptivity can be distinguished, ranging from manual to fully adaptive, with intermediate levels [

13].

In general, it is possible to customize the user interface for all IT systems, but the specifics of particular applications must be taken into account. A key issue is the number of users of the system that should have self-adaptation functionality available. In the case of intra-organizational applications (such as Enterprise Resource Planning systems—ERP, Workflow), there is a fixed and finely counted set of individuals or individual groups whose behavior should be analyzed and used in adaptation mechanisms [

14]. The situation is different for software applications that can have any number of users, such as e-commerce systems. As the number of users grows, so does the amount of information generated from customer journeys [

15], increasing the challenge of processing large amounts of data. Despite this limitation, the potential of AUI for e-commerce applications is being recognized. Attempts to bring personalization to e-commerce date back to the early days of this sales channel [

16]. The topic has become increasingly popular in recent years, as evidenced by the large number of publications highlighting the marketing relevance of such solutions [

17].

Another challenge in designing an AUI is placing the system in a business context. Approaches that work well under some conditions are not necessarily optimal under others, although attempts are being made to develop domain- and device-independent, model-based AUI methodologies [

18]. It is also necessary to consider the psychological aspects in order to optimize the involved users of information systems [

19].

Current trends in AUI development—the proliferation of AI and ML applications—also should not be overlooked [

20]. As early as the end of the 20th century, machine learning began to be considered for its potential in this area [

21], and today this approach is already widely used, leading to the so-called human-in-the-loop learning [

22]. The key to UI adaptation becomes information derived from continuous user tracking with dedicated tools. User preferences are an extremely important aspect in the design of self-adaptive systems due to their unique and dynamic nature [

23]. Interesting areas that could have a significant impact on the incorporation of user feedback into the UI adaptation process in the future are the increasingly popular Virtual Reality (VR) and Digital Twin approaches [

24]. However, the risks and negative consequences of AI applications in the human–computer interaction (HCI) domain cannot be overlooked [

25] and must be weighed against the potential benefits when deciding on human-centered AI solutions [

26].

Early attempts to personalize the user interface in e-commerce were limited in depth and scope [

27]. Over time, however, they have increasingly turned to data-driven solutions. An example of such an application can be a generic software platform for automatically generating web user interfaces based on analyzed behavioral patterns using machine learning [

28]. This type of approach could lead to the development of Intelligent User Interfaces [

29], which represent the next stage of AUI evolution. Solutions that automatically tailor the layout to the customer’s needs and preferences represent both a challenge and an opportunity for deeper personalization [

7]. This is especially important in channels such as e-commerce, where the competitive nature and lack of barriers to entry make it necessary to look for ways to stand out in order to attract and retain customers.

Various AI/ML techniques are used to personalize communication, which in e-commerce is mainly done through the UI. The use of clustering algorithms for customer segmentation is a very popular way of grouping users [

30]. The level of complexity of the proposed solutions varies from simple services aimed at identifying groups of users based on basic data sets to complex systems using deep learning [

31]. However, the use of ML in auto-adaptive systems poses several challenges. They include dealing with the uncertainty and dynamics of the changing environment, which requires the implementation of a lifelong learning approach [

32], and dealing with large data sets that need to be processed efficiently. For example, it can be noted that not all clustering algorithms can be used in practice due to the size of data sets containing e-commerce customer behavior [

33]. Computationally complex methods will not be effective in this business context, and an analysis of publications shows the dominance of the K-means algorithm, which allows combining high quality clustering with limited resource consumption [

34]. The costs associated with using machine learning techniques should be one of the criteria for designing the solution architecture [

35], as the return on investment, such as in e-commerce personalization, will ultimately be key for decision makers.

Product recommendation systems using various approaches such as Content-Based Filtering (CBF) and Collaborative Filtering (CF) are widely used in practice [

36]. While such systems are the most common way of personalizing communication in e-commerce, other approaches to the problem can also be found, such as the use of the Semantic Enhanced Markov Model [

37] and image-based product recommendations [

38]. It is also possible to use the clustering methods mentioned above to create personalized product lists that are shown to customers to encourage them to buy [

39]. However, product recommendations aren’t the only opportunities presented by the use of big data in e-commerce [

40], and UI personalization can be much broader, including techniques for adapting website layout.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that from the perspective of personalized UI applications in e-commerce, the issues related to the customer’s reception of the dedicated message cannot be overlooked. The product-related information, the consistency of product and background presentation, and the variety of product information presentation are closely related to the perceived quality of e-commerce systems for many years [

41]. On the one hand, measurable business results are a good measure of quality, but on the other hand, user satisfaction must be kept in mind [

42]. The specific nature of e-commerce means that loyalty is extremely important and should be prioritized over short-term benefits [

43]. There are also important issues related to the emotions that often drive online shopping decisions [

44] and influencing the decision-making process through non-coercive methods (known as digital nudging—DN [

45]).

An analysis of the literature on AUI reveals a research gap resulting from the widespread use of a single UI variant in e-commerce. While this is not a limitation for generating product recommendations that are always displayed in the same place for each customer, it can be a problem when there is a need for more intensive personalization that affects the entire layout. Furthermore, existing validation methods like A/B testing are limited to a binary decision framework. They lack a mechanism to formally handle inconclusive outcomes, often forcing a premature decision or the discarding of potentially valuable modifications. This paper addresses that gap by introducing a three-way decision model that explicitly incorporates an “indecision” or “delay” option, better suited for the iterative and complex nature of UI optimization.

Human-centered multi-variant UIs, based on user behavior and choices, offer a much wider range of possibilities for adapting the design and content presented to users, and their deeper analysis could make an interesting contribution to the development of intelligent user interfaces in e-commerce. An additional challenge is the automation of the UI adaptation process, leading to autonomous solutions that optimize the user experience without human intervention. These issues are addressed in this paper by analyzing the potential of ML-based self-adaptive multi-variant UIs to implement the concept of human-centered development to improve customer UX. The proposed solution is based on the concept of the Three-Way Decision Model (3WD), so it can work effectively in situations where a clear decision is not possible.

The goal of this paper is to introduce the concept of a self-adaptive multi-variant user interface based on a novel application of a three-way decision-making model, which allows for “accept”, “reject”, or “delay” decisions on UI changes. We present an end-to-end framework that integrates human-centered machine learning with this decision model to enable automated and scalable UI optimization for e-commerce platforms. To structure our investigation into this area, this study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: How can a three-way decision model be effectively adapted to create a self-adaptive framework for managing multi-variant user interfaces in an e-commerce environment?

RQ2: What is the practical impact of implementing a self-adaptive, multi-variant user interface on key e-commerce performance metrics, such as conversion rates and average order value?

RQ3: What are the key challenges and limitations encountered during the practical implementation of the proposed framework, and what directions do they suggest for future refinements?

By addressing these questions, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive validation of the proposed model, moving from theoretical concepts to practical implementation and evaluation. These questions directly address the research gap identified in the literature, particularly the limitations of static interfaces and binary (A/B testing) decision frameworks.

This paper makes several original contributions. Theoretically, it introduces a novel application of the three-way decision (3WD) model to the domain of UI adaptation, providing a formal mechanism to handle the uncertainty inherent in A/B testing. Practically, it presents an end-to-end framework for a self-adaptive, multi-variant e-commerce interface that goes beyond simple personalization. Methodologically, it integrates human-centered machine learning with this decision model to enable automated and scalable UI optimization. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 details the methods behind the framework.

Section 3 presents the results of our empirical study.

Section 4 discusses the implications and limitations of our findings, and

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary and directions for future research.

2. Methods

2.1. E-Commerce UI Self-Adaptation Mechanism

There are many ways to personalize the user interface in e-commerce. Product recommendation systems are the most common in practice, but the needs and opportunities are undoubtedly greater. One approach that takes a comprehensive approach to tailoring the UI to the specific characteristics of particular customer groups is the multi-variant user interface (MultiUI) [

7]. Such a solution can operate in an expert-managed or self-adaptive mode. The two approaches differ in the process of optimizing the UI variant served to specific groups of customers, obtained through clustering based on behavioral data. In the first case, decisions about the selection of personalized modifications are made by a UX specialist and then verified experimentally. In the second case, the adaptation is automatic, with individual modifications being introduced and evaluated in successive iterations.

The general scheme of the platform supporting a multi-variant user interface is shown in

Figure 1.

The first component is responsible for collecting data on customer behavior. In order to make quality recommendations, it is crucial to gather all possible information about how customers use the online store. This means not limiting yourself to basic actions such as adding a product to the cart or placing an order, but capturing all activities (e.g., filter settings, selecting product attributes, developing descriptions, searching) and their context (pages where the action was performed and time spent on the site). Web analytics systems such as Google Analytics or Matomo can be used for this purpose. It is important to record customer behavior in the form of a

clickstream, which allows detailed analysis of user behavior and, if necessary, identify bottlenecks and critical steps in the purchase path (e.g., those where the purchase is interrupted). An example of the range of behavioral and contextual data collected by the Matomo system is shown in

Figure 2.

Since the collected data includes not only user behavior but also contextual information, it is possible to use comprehensive knowledge about the customer during clustering, thus increasing the quality of the results obtained.

Another important aspect of data collection is privacy. Today’s market standards place increasing emphasis on the informed consent of customers to the tracking of their activities, and regulations enforce great care in the collection and processing of personal data. It is an ethical prerequisite that all data collection for the purposes described in this paper is performed only after obtaining explicit and informed user consent, in compliance with regulations such as GDPR. This includes being transparent with users about what data is being collected and how it will be used to personalize their experience. Therefore, in order to collect data on customer behavior, it is necessary to obtain their consent (e.g., by adding relevant marketing consents) and to anonymize the information (e.g., by tokenizing users). Data about how customers use the online store is used in two ways within the platform described: it forms the basis for clustering users using machine learning algorithms, and it allows analyzing the effectiveness of changes implemented through the self-adaptation mechanism.

Tokens associated with the devices used can be used to ensure privacy, but these will not always be unique identifiers. For this reason, it is worth considering the use of Universal Unique Identifiers (UUIDs) [

46] stored in cookies to identify users. This solution also has drawbacks (e.g., inability to distinguish between multiple clients using the same device, or sensitivity to applications that restrict the use of cookies), but because of its simplicity it may be sufficient.

The second component of the platform is designed to group customers based on their characteristic behavior. Due to the large amount of data to be processed, clustering algorithms commonly used for customer segmentation are useful [

34]. However, it is important to note that not all clustering methods are equally useful for grouping customers in order to serve them with specific UI variants. Three main aspects should be considered when choosing an algorithm: computational complexity, clustering quality metrics, and business context.

Computational complexity affects the resources (primarily memory and processor power) that must be allocated to successfully perform clustering. Some algorithms may not be able to handle large data sets due to insufficient computing power. Although there are solutions today that allow resources to be scaled, this is not always possible to the desired level and is usually expensive. Given these limitations, it is worth considering using methods that cluster large datasets well, such as K-means [

33].

Several indicators can be used to evaluate the quality of clustering, including the Silhouette Score [

47], the Calinski–Harabasz Index [

48], the Dunn Index [

49], and the Davies–Bouldin Index [

50]. They measure various characteristics of the clusters, such as the degree of cohesion and separation of data points, the similarity between objects, and the compactness of the clusters. When selecting measures of clustering quality, it is important to keep in mind that the resulting recommendations may differ from each other and that it is better to rely on an aggregated indicator that considers several metrics rather than a single measure. In addition, the values of the indicators depend on the number of clusters (

k), which makes it a challenge to determine this value [

51].

An often overlooked criterion for selecting a clustering algorithm, but a key one for practical use, is the fit with the business context. When serving dedicated UI variants, the correct distribution of customers is the key, especially in terms of the number of customers in each cluster. The self-adaptation mechanism requires the collection of a sufficient amount of feedback, which means that dedicated UI variants must be served to many customers in order to be evaluated. It should also be noted that in online stores, the percentage of returning users is typically in the tens of percent (on an annual basis) [

52], and the conversion rate is typically a few percent [

53]. This means that for clusters with too small number of customers, a dedicated UI variant is rarely served and it would take a very long time to collect data to assess macro conversion (resulting from orders placed). In turn, prolonging the time to evaluate the changes made increases the risk of external factors influencing the evaluation, which could skew the results. Because of these limitations, clustering algorithms should be chosen so that the division of customers into clusters is as even as possible, and the number of users in the smallest cluster is not less than an assumed threshold (e.g., 5% of the total population). In addition, these requirements exclude algorithms that are not guaranteed to generate a certain number of clusters (e.g., DBSCAN), since there should not be too many clusters due to the cost of designing and maintaining UI variants. A comprehensive comparative analysis of different clustering methods, including K-means, DBSCAN, and Gaussian Mixture Models, was conducted separately to determine the most suitable approach for this e-commerce context [

54]. That analysis concluded that the K-means algorithm provided the best balance of computational efficiency, cluster quality, and segment size equality, making it the most practical choice for creating actionable user groups for A/B testing of UI variants.

The third component is responsible for assessing the impact of changes on customer choices in the online store and is a key element of the self-adaptation mechanism (

Figure 3).

The decision model is based on a set of metrics to verify whether the implemented changes have positively impacted user behavior. These metrics can include macro conversion metrics related to orders placed, such as Conversion Rate (CR) and Average Order Value (AOV), as well as micro conversion metrics related to single actions, like Click Through Rate (CTR), or sequences of actions, such as Partial Conversion Rate (PCR [

7]). Descriptions of the metrics can be found in

Table 1.

This last indicator can be flexibly adapted to the specifics of the changes being studied and allows the analysis of different sequences of customer activity, together with the specific priorities of certain events. Unlike the others, it is not commonly used, hence the need for clarification. PCR is calculated according to the following formula [

7]:

n is the number of sessions related to customers from the cluster c,

s is the number of activities within session n,

is the calculated PCR metric value for the cluster c,

is the score of an activity j during a session i,

This metric offers considerable flexibility in selecting and prioritizing activities for study by assigning different CVV values to actions. This versatility is valuable for studying the impact of changes on different elements of the user interface without having to wait for the purchase process to complete.

Detailed configuration of the self-adaptation mechanism allows defining rules for accepting or rejecting changes. It can also include additional checks if the results are inconclusive. In the simplest case, it can be assumed that a change is accepted if at least one of the selected indicators for the custom UI has a value that is at least X% better than the value for the standard UI (acceptance threshold X is set as a parameter value), and the values of the other indicators do not deteriorate. Similarly, a rejection rule can be defined—if at least one of the indicators for the dedicated UI has a value that is at least X% lower than the value of that indicator for the standard UI, and the values of the other indicators are not improved. In ambiguous cases, the study can be repeated in the next period, with a finite number of iterations. If subsequent iterations do not result in a decision, a decision should be made based on the predefined settings of the system—accepting or rejecting changes that ambiguously influence customer decisions.

The fourth component is the design of the changes made to the UI variants. They result from the set of potential modifications that are the input to the described auto-adaptation mechanism and decision algorithm. Despite the common collection of analyzed UI modifications, the customization of UI variants takes place independently, and the time taken to check all options may vary. This is due to the fact that feedback is collected at different speeds, depending on the frequency of use of the e-shop and the behavior of users from specific clusters.

The last component allows for serving dedicated UI variants. In adaptation mode, client clusters are split, and one part receives a standard UI while the other receives a dedicated UI. This allows the impact of the changes to be compared, evaluated, and justified.

In the mechanism’s standard operation mode, all cluster clients receive a customized, dedicated UI variant, and the system returns to adaptation mode as new potential changes are added to the analysis.

2.2. Adaptation of the 3WD Model in Decision-Making Algorithms

The proposed decision solution of self-adaptation is based on the 3WD concept, which is rooted in decision theory and granular computing. This framework extends the traditional two-way decision model (‘accept’ vs. ‘reject’) by introducing a third option, often referred to as deferral, delay, or indecision. Such an approach is advantageous because it allows for postponing the decision to accept or reject a UI modification in order to further verify its impact on e-commerce customer behavior. Formally, the application of 3WD causes decisions to fall into three categories based on the level of certainty or risk:

Positive Area (P): High certainty supports acceptance of the UI change under analysis;

Negative Area (N): High certainty supports rejection of the analyzed UI change;

Boundary Area (B): Uncertainty or risk suggests deferring the decision for further analysis (e.g., re-verifying the impact of the change) or action (e.g., expert decision to reject/accept the change).

With such designations, the entire framework (labeled U—the universe of decision objects) can be described by the relation: and . Traditional 3WD assumes that for a given object function represents some measure of certainty or probability. The decision-making process, in turn, is based on two thresholds ( and ), where , and:

the assignment to area P occurs if ;

the assignment to area N occurs if ;

the assignment to area B occurs if .

However, this single-criterion approach is insufficient for complex UI modifications, which require evaluating multiple performance indicators simultaneously. In such cases, there are multiple measures of certainty, which can be represented as: , , , etc., where each measure corresponds to a different metric that describes the impact of UI changes on e-commerce customer behavior. Similarly, instead of two thresholds ( and ), there appear thresholds, where n is the number of performance indicators of the analyzed changes. The thresholds can be labeled respectively: , , , , , , etc. Assignment to areas in such a situation must take into account all decision-making criteria, and an extremely restrictive variant can be stated as follows:

to area P if ∧∧;

to area N if ∧∧;

to area B if ∨∨.

Less restrictive options may assume different rules for allocation to areas (e.g., exceeding thresholds for most decision factors).

This 3WD model adaptation proposal was verified in an experimental study to evaluate its usefulness in practical applications in the process of accepting UI modifications in e-commerce.

3. Results

This section presents the empirical results of our study, conducted to directly address our research questions. We begin by detailing the preparation of the UI self-adaptation mechanism (addressing RQ1) and then present the quantitative outcomes of the two experimental iterations, which provide a direct answer to RQ2.

3.1. Preparation of the UI Self-Adaptation Mechanism

To demonstrate how the described UI self-adaptation mechanism works, a sample study was conducted in an online store operating in the clothing industry. The research was conducted using the platform developed by Fast White Cat S.A., an official Adobe partner founded in 2012 and an experienced global e-commerce company.

The general architecture of the

platform is shown in

Figure 4.

The solution was developed using the following technologies [

7]: PHP 8.1+, Symfony 6.1+, API Platform 3+, and Docker.

The survey consisted of several phases. The first was to collect data and group customers. Based on the previously mentioned approach [

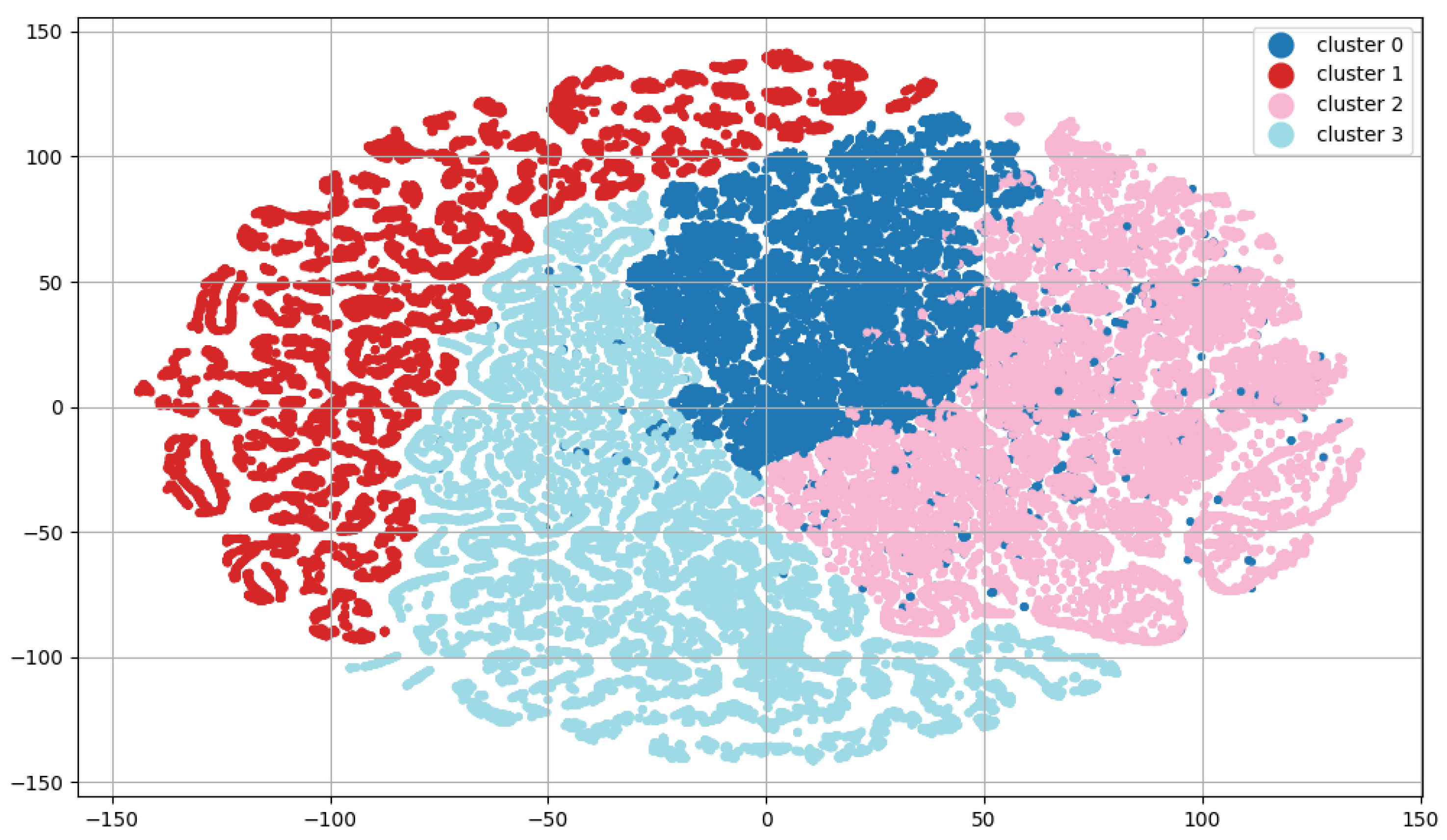

54], users were divided into 4 clusters using the K-means algorithm, based on a training data set of 670,766 user sessions. The number of clusters (k = 4) was determined to be the optimal choice by evaluating a range of clustering quality indicators, including the Silhouette Score, Calinski–Harabasz Score, and Davies–Bouldin Score, which collectively indicated the most distinct and meaningful segmentation at this value.

Figure 5 shows the visualization of the clusters using the t-SNE technique [

55]. The t-SNE dimensionality reduction was performed using the Scikit-learn library in Python 3.12, and the resulting two-dimensional data was plotted using Matplotlib 3.8.2 to generate the visualization.

The choice of K-means resulted in optimal cluster sizes, with the smallest cluster containing almost 20% of the study population. The relatively small variation in the number of users in the clusters allows for a flexible choice of sample group—regardless of the choice made, a similar number of customers will be served with a dedicated UI variant during the change verification phase. The following cluster sizes were obtained: 29,297 (Label0), 30,835 (Label1), 45,463 (Label2), 45,299 (Label3), meaning that the smallest cluster contained 19.42% of the total user population. The cluster designated Label2 was selected for further analysis as it contained the most active users, thereby maximizing the potential for collecting statistically significant feedback.

The values of the classical indicators describing the quality of clustering:

Silhouette Score = 0.278644;

Calinski–Harabasz Score = 33,392.592567;

Davies–Bouldin Score = 2.095141;

Entropy = 1.365417

Also indicate that this combination [clustering method − number of clusters] is a good option.

In the next phase, two sets of UI changes suggested by a UX expert were designed. The first set contained seven changes, including the layout of the filters, the search bar, the item description on the product card, the free shipping information, and the color scheme of the widgets.

The second set included 5 changes in the following areas: image gallery settings, size and position of the price and item ID on the product card, menu appearance (change to mobile-like), and footer settings (

Table 2).

The next phase of experimental research involved the application of the UI self-adaptation algorithm. Both sets of modifications were reviewed sequentially. If the first set of changes was accepted, the changes from the second set would be added to the changes from the first one. If the first set was rejected, the changes it contained would not be included in the second part of the study.

The experiment assumed one iteration of testing for each set of changes (without retesting in the case of an inconclusive recommendation). Implementing the proposed mechanism required additional assumptions regarding the decision thresholds. These thresholds were not chosen arbitrarily, but they were defined by aligning a risk-averse business strategy with established statistical principles from A/B testing [

56]:

It is important to note that these thresholds are not fixed constants but are configurable parameters of the framework. Their optimal values can be tuned based on a specific business’s risk appetite, market conditions, and the specific goals of the optimization efforts (e.g., prioritizing user engagement over immediate revenue).

The decision rule used in the recommendation system was based on two macro conversion indicators ( and ) and one micro conversion indicator (). They correspond to the , , measures from the formal model described in the previous section.

The latter took into account the following user actions: moving from the home page or listing to the product card (10 points each), moving from the home page to the listing (10 points), adding the product to the cart (20 points), moving from the product card to another product card (5 points). These values were assigned by the UX expert based on the action’s proximity to the final purchase decision, with actions higher in the conversion funnel (e.g., adding to cart) weighted more heavily than exploratory actions (e.g., viewing another product). This structured approach, while relying on expert judgment, provides a transparent and logical framework for prioritizing user actions that more strongly indicate purchase intent.

3.2. The First Iteration of Verifying Implemented UI Changes

During the first iteration of the analysis, information was collected on 6001 user sessions from the selected cluster, during which the dedicated UI variant was served 2983 times and the standard variant was served 3018 times. The CR, AOV and PCR values are shown in

Table 3. To determine if the observed differences were statistically significant, we conducted hypothesis testing. For the Conversion Rate, which is a proportional metric, we used the chi-square (

) test of independence. For the Average Order Value and Partial Conversion Rate, which are continuous metrics, we used the two-sample independent

t-test. All tests were performed with a significance level (

) of 0.05, corresponding to a 95% confidence level. In addition to determining statistical significance with

p-values, we calculated the practical significance or effect size of the changes. For the proportional CR metric, we used the Phi (

) coefficient, and for the continuous AOV and PCR metrics, we used Cohen’s

d. This allows for a standardized measure of the magnitude of the impact, independent of sample size, where an effect size of ∼0.2 is small, ∼0.5 is medium, and ∼0.8 is large.

The percentage change was calculated using the following formula:

where:

is the percentage change in the value of the

X indicator,

is the value of the

X indicator for the dedicated interface, and

is the value of the

X indicator for the standard interface.

The “++” symbol in the last line indicates that the value exceeds the assumed positive threshold, and the “+” symbol indicates a higher indicator value for the specific UI, but below the assumed threshold. A “-”symbol indicates a worse indicator value for the dedicated UI variant, but not exceeding the assumed rejection threshold.

Analysis of the results obtained allowed the recommendation system to accept the first set of changes. For two indicators (

and

), the values for the dedicated interface were significantly higher and exceeded the threshold (

Figure 6). The statistical analysis confirms this conclusion, with

p-values well below 0.05, indicating that these improvements are highly unlikely to be due to random chance. Furthermore, the calculated effect sizes quantify the practical impact of these changes. The large effect size for CR (

= 0.82) and medium effect size for AOV (

d = 0.55) confirm that these improvements were not just statistically significant, but also practically meaningful. The values obtained for the third indicator (

) were similar for both UI variants, but with a minimal advantage for the dedicated interface. This is reflected in the high

p-value (

p = 0.34), which shows the 1.01% difference is not statistically significant and a trivial effect size (

d = 0.04), confirming the lack of any real impact from the changes on this specific metric. On this basis, the changes were confirmed and incorporated into the new standard UI in the next iteration of the study.

3.3. The Second Iteration of Verifying Implemented UI Changes

In the second iteration of the research, 6175 customer sessions were identified from the analyzed cluster. During this period, the dedicated UI variant was served 3057 times, and the standard variant (taking into account the modifications from the first iteration) was served 3118 times. The indicator values obtained in this part of the study are presented in

Table 4.

This time, the results were inconclusive. For no indicator did the difference between the dedicated and standard interfaces exceed the threshold (

Figure 7). The statistical tests for all three metrics yielded

p-values greater than the 0.05 significance level, confirming that none of the observed changes (positive or negative) were statistically significant. Furthermore, the calculated effect sizes were trivial to small for all metrics: CR showed a small positive effect (

= 0.15), AOV a small negative effect (d = −0.19), and PCR a trivial effect (d = −0.03). This combination of non-significant results and small effect sizes provides strong evidence that the second set of UI modifications had no meaningful impact—either positive or negative—on customer behavior. Two indicators showed a deterioration in the quality of the dedicated interface, and one indicated an improvement. In this situation, the recommendation system rejected the set of changes according to the decision rule and the additional assumptions made. This outcome was technically correct based on the predefined rules, but it highlighted a key practical challenge—the system’s sensitivity to marginal, statistically insignificant changes, an issue that will be explored further in the discussion.

4. Discussion

The experimental results provide significant insights into the practical application of the 3WD model for UI adaptation. In this section, we synthesize these findings to answer our research questions more broadly. We discuss the implications of our results for RQ2, focusing on the observed impact on e-commerce metrics, and then address RQ3 by analyzing the challenges and limitations revealed during the study, proposing avenues for future research that will be critical for maturing this technology.

The presented algorithm for adapting UI modifications to e-commerce customer behavior, based on 3WD model, is a flexible tool that can be developed in multiple directions.

Figure 8 illustrates the algorithm’s real-world application, where it correctly processed both a clear positive outcome and a complex, inconclusive one. The first iteration resulted in acceptance, while the second led to a rejection. This demonstrates the framework’s primary strength—its ability to provide a structured, automated response not just to clear wins, but also to ambiguous results that would typically require manual analysis and debate in traditional A/B testing. This formal handling of uncertainty is what makes the tool uniquely robust for real-world e-commerce environments where inconclusive outcomes are common.

The presented experimental results show the general principle of its operation, but contain simplifications that warrant deeper discussion. Primarily, the practice of grouping multiple UI changes into a single test, while expedient, creates analytical challenges. Our approach successfully assesses the aggregate impact, but it cannot deconstruct the outcome to identify the specific drivers. This “bundling” risks a valuable modification being rejected because it was packaged with a poor one, or vice-versa. This is a critical trade-off in optimization—while testing every atomic change is often infeasible due to the statistical confidence required, large bundles obscure causality. Therefore, a key takeaway for practitioners is the need for a strategic methodology for bundling—grouping changes thematically (e.g., all related to the checkout process) or by anticipated impact—to find a practical balance between testing velocity and analytical clarity.

A key practical insight from this study is the need for a more sophisticated handling of marginal outcomes. This issue became evident in the first iteration, where the PCR indicator’s +1.01% improvement was positive but marginal. For two indicators, the values for the dedicated interface were significantly higher than for the standard interface, but for the indicator the difference was about 1%. Fortunately, in this case, the dedicated variant was slightly better, so the set of modifications was accepted. However, if the standard interface had been slightly better, the algorithm would have considered such modifications as having an indeterminate effect. We therefore propose introducing a “dead zone” or indifference margin (e.g., or %) around a 0% change. Results falling within this range would be formally classified as neutral, preventing statistically insignificant noise from triggering a rejection or complicating an acceptance decision. This is not merely a technical tweak—it is a crucial enhancement to the 3WD model’s practical application. It acknowledges the stochastic nature of user behavior and prevents the system from overreacting to randomness. Implementing this margin would make the framework more robust and efficient, reducing the need for manual review of inconclusive tests and better aligning the automated decisions with real-world business logic.

Another key consideration is the methodology for weighting the Partial Conversion Rate indicator. In this study, the weights were assigned by a UX expert based on established conversion funnel principles. We acknowledge this introduces an element of subjectivity, which is a limitation of the current implementation. This expert-led approach, while practical, represents a potential point of failure or bias. A more advanced and objective system would move towards data-driven weighting. For instance, the weight for each user action could be dynamically calculated based on the historical, empirical probability that a user performing that action will ultimately complete a purchase. Such a model would transition the PCR from an expert-guided metric to a more objective, empirically validated indicator of user engagement and purchase intent. This shift from human-heuristic to machine-derived weights is a critical step towards creating a truly autonomous and intelligent optimization system, directly addressing the limitations identified in RQ3 and setting a clear agenda for future research.

A related direction for future research is the justification and optimization of the decision thresholds ( and ) themselves. Our choice of and was based on a sound, risk-averse business strategy common in e-commerce. However, these static values may not be optimal for all contexts. A more advanced implementation of our framework would involve a process for tuning these thresholds. For instance, a business could perform a sensitivity analysis using historical experiment data to model the impact of different threshold levels on long-term growth and risk exposure. Furthermore, one could develop an adaptive threshold mechanism, where the values of and are dynamically adjusted based on factors like the maturity of the website, business seasonality, or the company’s shifting tolerance for risk. This would transform the thresholds from static parameters into a dynamic component of a larger optimization strategy, representing a significant step towards a more autonomous and intelligent system.

Beyond the technical implementation, it is crucial to consider the ethical dimensions of automated personalization. While the goal of this framework is to improve user experience, any system that tracks user behavior carries a responsibility to do so ethically. The core ethical challenge lies in balancing the benefits of a personalized interface with the user’s right to privacy and autonomy. Transparency is paramount: users should be clearly informed that their experience is being dynamically adapted and have control over their data. Furthermore, personalization algorithms must be designed to avoid manipulative practices (so-called “dark patterns”) that exploit cognitive biases to drive conversions against the user’s best interests. The framework presented here is intended as a tool to serve users with more relevant content, not to coerce them. Future research should continue to explore methods for building “explainable AI” into such systems, allowing for greater transparency and user trust.

While the study effectively demonstrates the proposed framework’s viability, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, which in turn suggest directions for future research. The experiment was conducted in a single clothing online store. Future studies should validate the model across different e-commerce sectors, such as electronics or groceries, which may feature different customer decision-making processes. A key limitation of the current study is that the experiment was conducted in a single online store within the clothing industry. This context specificity restricts the generalizability of our findings. Therefore, a critical next step is to extend the validation of the framework across a diverse range of e-commerce sectors. Future studies should test the model in domains such as electronics, groceries, or digital services, which are characterized by different customer decision-making processes, purchase cycles, and user interface requirements. Such multi-domain validation would be essential to confirm the robustness of the 3WD model and refine its application for broader practical use.

The second key limitation of our study is its cross-sectional nature, which captures only the immediate impact of UI modifications. This approach cannot account for long-term user experience phenomena such as the novelty effect, where an initial performance uplift may be due to the change itself rather than its intrinsic quality, or adaptation fatigue, where users may become disoriented or frustrated by a constantly evolving interface. To address this, future research must include a longitudinal analysis. Such a study would involve tracking user cohorts over an extended period (e.g., several months) and focusing on long-term engagement and retention metrics, such as repeat purchase rate, customer lifetime value, and churn rate. This would provide crucial insights into the sustainable impact of the adaptive framework on customer loyalty and trust.

Future research could also move towards a more autonomous system by integrating machine learning models, such as reinforcement learning, to not only evaluate but also generate UI modification proposals, thereby reducing the reliance on human experts. Finally, incorporating qualitative user feedback through surveys or interviews could provide deeper insights into user satisfaction and trust, complementing the quantitative behavioral metrics used in this study.

It is also worth noting the importance of the threshold used in the decision algorithm. It determines the sensitivity of the self-adaptation mechanism. In the studies described, a threshold of was used. Increasing the threshold would result in a higher probability of rejection or acceptance of the modification, and thus a slower but safer adaptation of the UI variant to the customer group. On the other hand, lowering the threshold would make the decision easier and faster, but increase the risk of a false positive conclusion. Optimizing the threshold is clearly a challenge that should be addressed in further research. This issue is related to the timing of feedback collection. If the e-shop’s customers return frequently, providing an opportunity to analyze their behavior with a modified UI variant, a higher threshold could be considered. However, if there are few returning users, a lower threshold may be necessary due to the timing of the study.

5. Conclusions

This paper has presented and empirically validated a self-adaptive framework for e-commerce user interfaces, marking a significant advancement over traditional optimization methods. Our primary contribution is the novel adaptation of the three-way decision model to the domain of UI personalization. By moving beyond the rigid, binary paradigm of conventional A/B testing, we have furnished a more nuanced “accept-reject-delay” mechanism that is inherently better suited to the complexities of user behavior. This methodological shift addresses a key gap in the A/B testing literature, which often lacks a formal process for handling the ambiguous or statistically insignificant outcomes frequently encountered in practice.

Our work also extends the broader e-commerce personalization literature. While much prior research has focused on content personalization through methods like collaborative and content-based filtering for product recommendations, our framework addresses the relatively underexplored challenge of adapting the UI layout and interaction design itself. By doing so, we move from personalizing what a user sees to how they interact with the entire platform.

In addressing our research questions, we have demonstrated both the theoretical soundness and practical utility of this approach. We successfully designed and implemented the 3WD framework (RQ1), showing that it can be effectively operationalized to manage UI modifications. Our experimental results confirmed that this system can drive statistically and practically significant improvements in key performance metrics (RQ2), leading to enhanced conversion rates and average order values. Finally, through a critical discussion of the study’s challenges and the need to optimize its decision parameters, we have outlined a clear path for future refinement and development (RQ3).

The implications of this work are twofold. For practitioners, our framework offers a tangible pathway to automate the delivery of personalized e-commerce experiences, fostering stronger customer relationships and sustainable growth. For the academic community, our study serves as a proof-of-concept, demonstrating that decision-making models from granular computing can be successfully applied to solve complex problems in Human–Computer Interaction and opening new directions for research in intelligent, adaptive systems.

By integrating machine learning algorithms, user data analysis, and responsive design, e-commerce platforms can tailor their interfaces to individual users. This approach enhances user satisfaction and positively impacts conversion rates and overall business success. As the crucial bridge between business and consumer, the user interface’s ability to adapt to customer behaviors and preferences is paramount. Currently, however, most UI personalization in e-commerce is limited to product recommendation engines. Our research demonstrates a viable path forward, showing that deeper, layout-level adaptation is not only possible but can be managed through a robust, data-driven, and automated framework.

To meet evolving market dynamics, the exploration of deeper, specialized interactions is necessary. The multi-variant user interface is one such innovative solution, offering customers layout options tailored to the needs of different user demographics instead of a single, static design. While its implementation is a complex undertaking—requiring consideration of specific e-commerce behaviors, customized data processing, and new mechanisms for delivering UI modifications—the potential economic and marketing benefits justify the investment.

The system framework presented in this paper facilitates the deployment of a multi-variant e-commerce user interface. It includes the ability to independently modify specific variants, going beyond the commonly used A/B testing. The operation of the self-adaptation feature is elucidated through an empirical study. Its assumptions were tested in practice and the conclusions were used to make improvements. In addition, the paper proposes a strategy for the further development of this methodology to improve the fine-tuning of user interface variants through the application of ML algorithms.

Our approach successfully embeds the theoretical principles of the three-way decision model into a practical, real-world business context. The research conducted confirmed its effectiveness and identified potential limitations and directions for development. Future work should focus on validating this model across diverse e-commerce domains, exploring the long-term effects on user experience, and developing more autonomous ML-driven systems for generating UI modifications. The constant evolution of technology and the ever-changing landscape of user expectations underscore the importance of ongoing research and enhancement in this area. As e-commerce UI self-adaptation becomes more sophisticated, it opens the door to a future where online shopping experiences are intuitive, efficient, and enjoyable for users. By prioritizing the improvement of the user experience through adaptive interfaces, companies can build stronger customer relationships, foster brand loyalty, and position themselves for sustainable growth in the dynamic world of online commerce.