Exploratory Proof-of-Concept: Predicting the Outcome of Tennis Serves Using Motion Capture and Deep Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Video Analysis with Computer Vision

2.2. Motion Tracking Technology

3. Materials and Methods

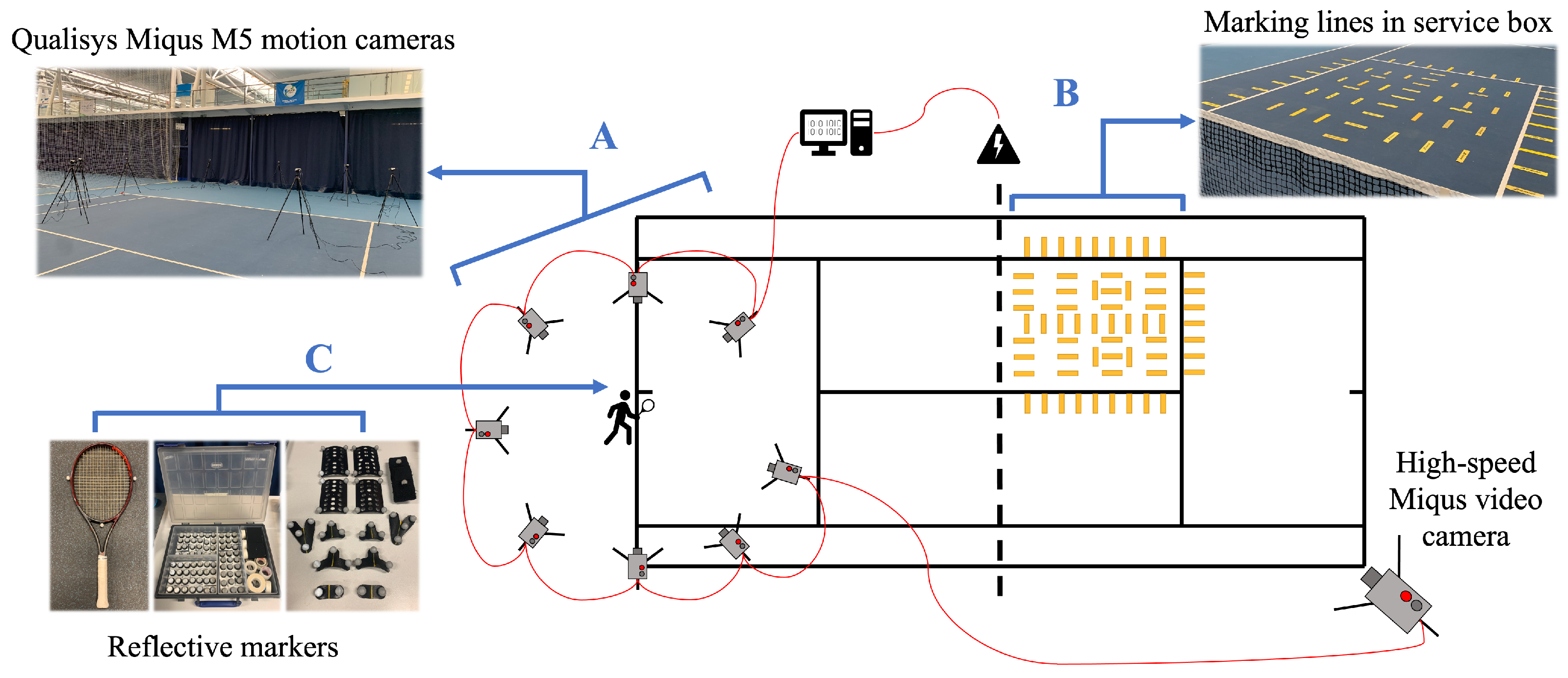

3.1. Experimental Setup

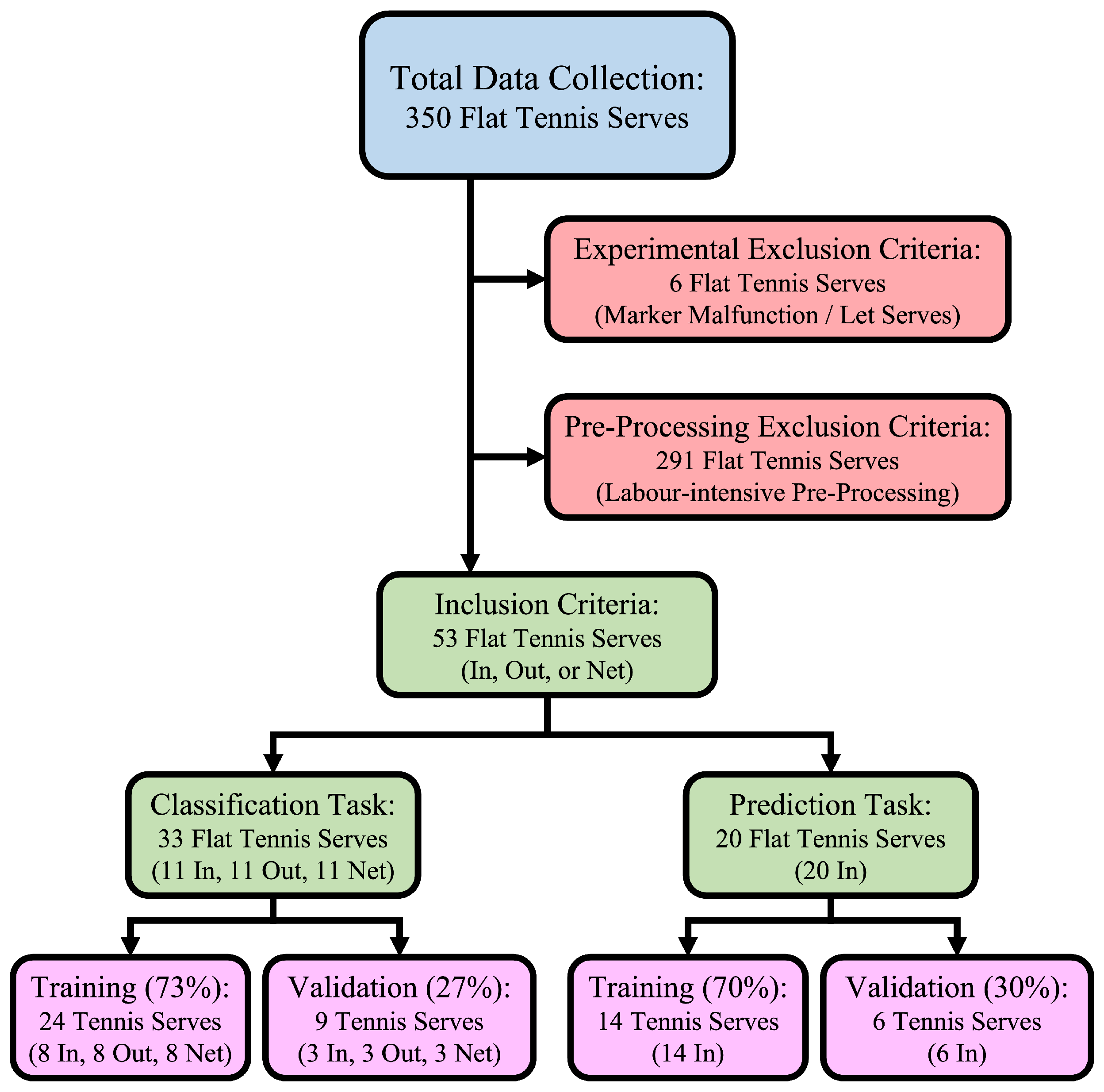

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

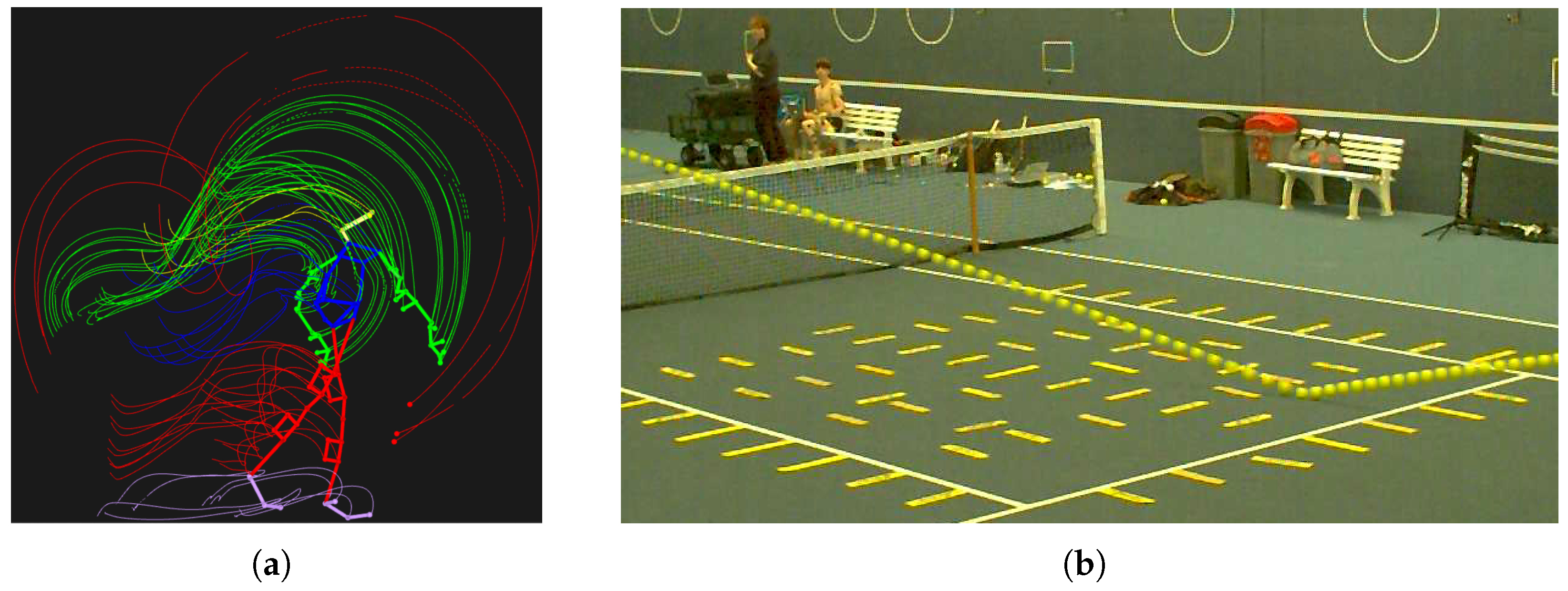

3.2.1. Motion Data

3.2.2. Serve Outcome Data

3.3. Machine Learning Models

3.3.1. Stacked Bidirectional LSTM

- Five Bidirectional Layers: Using 256 hidden units within each layer;

- Five Dropout Layers: Set with a Dropout of 0.1;

- Two Dense Layers: With 128 and 3 units, respectively. L2 Regularization ( = 0.7) was applied only to the final Dense Layer, which also used “softmax” activation;

- Total parameters: 7,352,835.

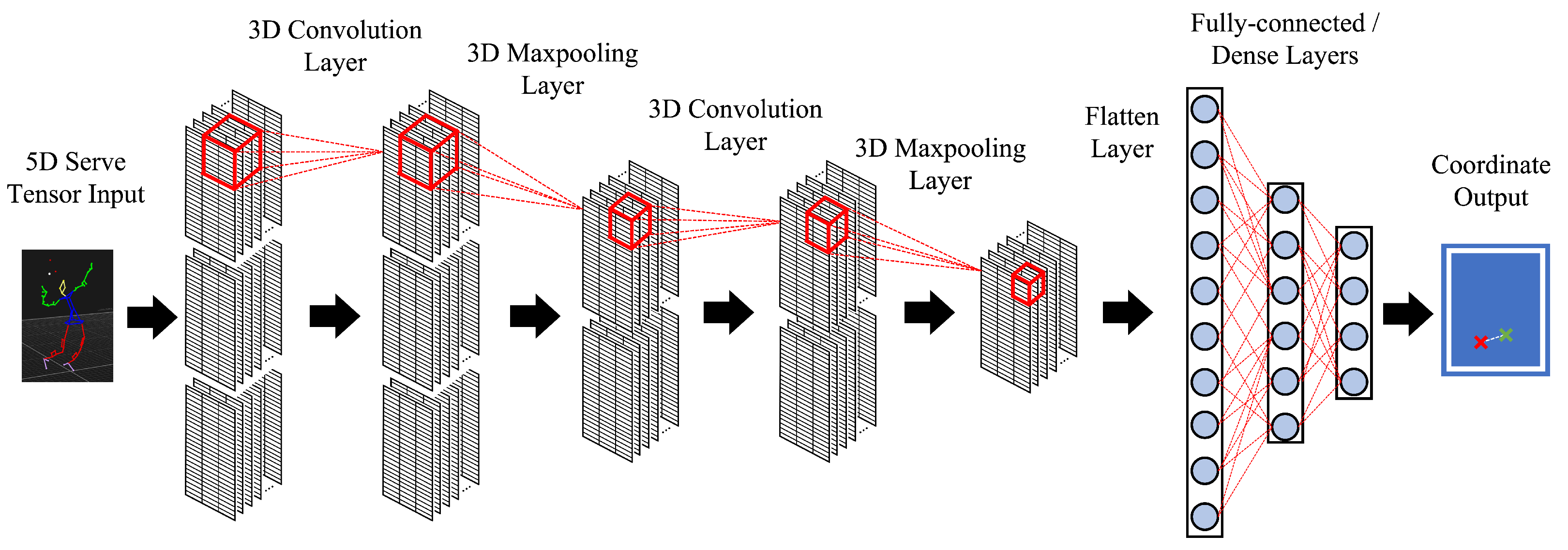

3.3.2. The 3D Convolutional Neural Network

- Three 3D Convolutional Layers: Using 32, 64, and 128 filters, respectively;

- Three 3D Maxpooling Layers: Maxpooling sizes of (2, 2, 2) and padding set as “same”;

- Three Activation Layers: Each activation layer set as “relu”;

- One Dense Layer: With 2 units and “linear” activation;

- One Flatten Layer: Placed between the Convolutional and Dense layers;

- Total parameters: 180,290.

4. Results

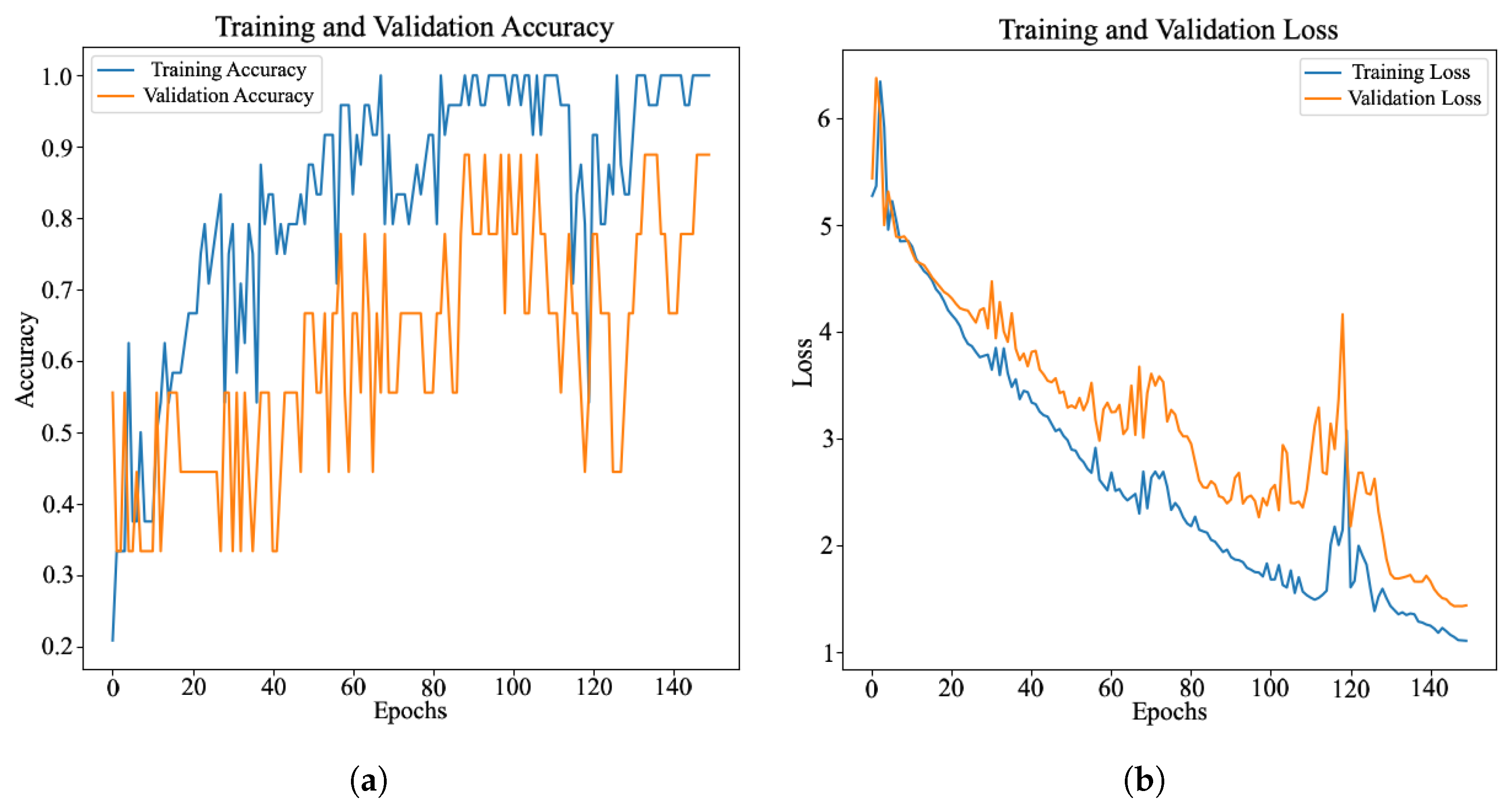

4.1. Tennis Serve Classification

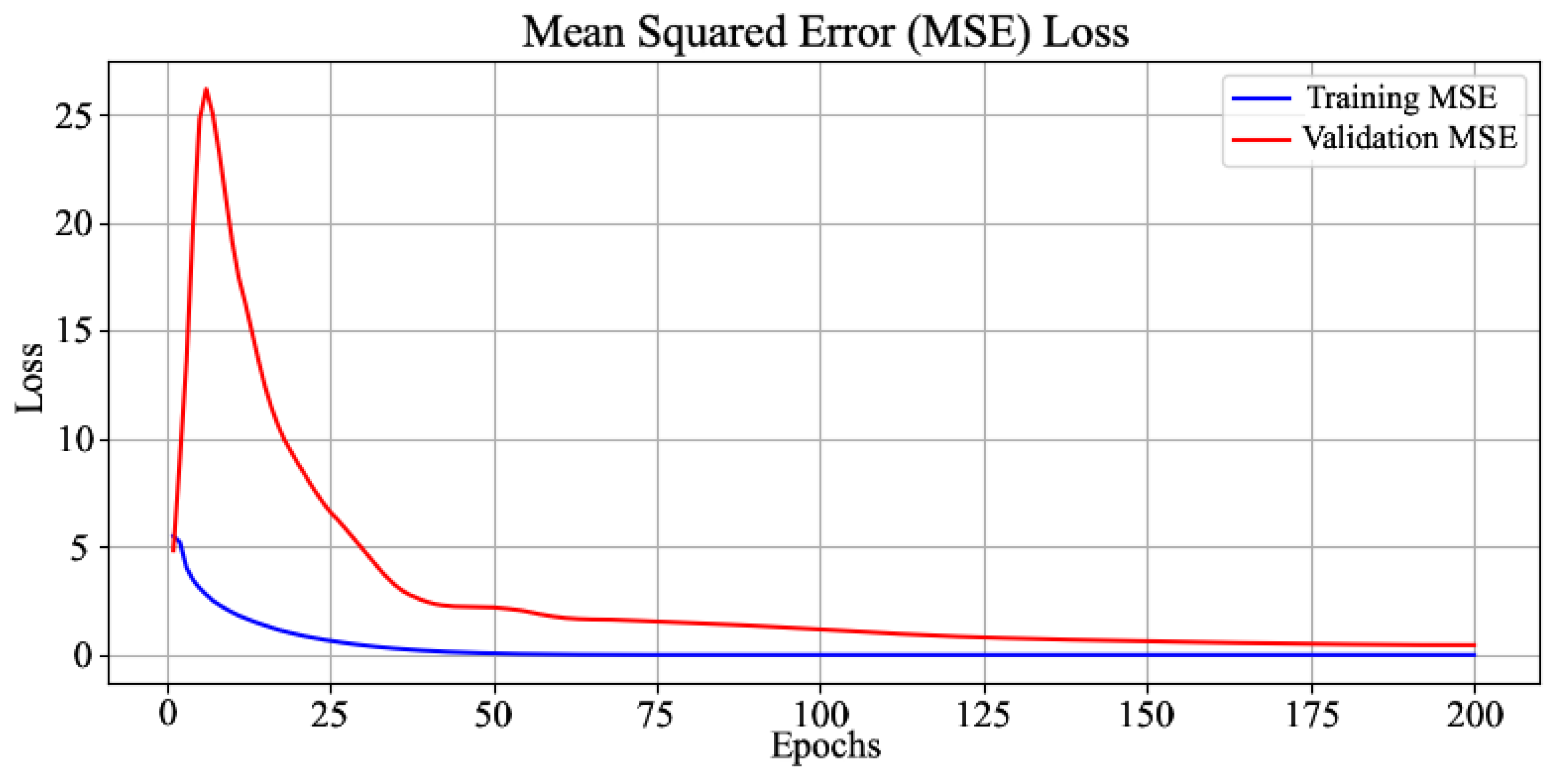

4.2. Tennis Serve Prediction

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crego, R. Sports and Games of the 18th and 19th Centuries; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ITF. ITF Global Tennis Report; International Tennis Federation: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lammer, H.; Kotze, J. Materials and tennis rackets. Mater. Sports Equip. 2003, 1, 222–248. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, R.; Alam, F.; Subic, A. Review of tennis ball aerodynamics. Sports Technol. 2008, 1, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, B.; Dureja, G. Hawk Eye: A logical innovative technology use in sports for effective decision making. Sport Sci. Rev. 2012, 21, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, Y.S.; Pal, U.S. Innovative evolution of technology used among racket sports: An overview. J. Sports Sci. Nutr. 2022, 3, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.; Smith, A. Sensors and data retention in Grand Slam tennis. IEEE Sens. Appl. Symp. 2018, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R. Performance analysis: Can bringing together biomechanics and notational analysis benefit coaches? Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2001, 1, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, B.; Marsh, T.; Blanksby, B. A three-dimensional cinematographic analysis of the tennis serve. Int. J. Sport Biomech. 1986, 2, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Okamura, S.; Murakami, S. Performance analysis in tennis since 2000: A systematic review focused on the methods of data collection. Int. J. Racket Sport. Sci. 2022, 4, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, Y.; Mottet, D.; Slangen, P.; Montesinos, P. A review of 3D human pose estimation algorithms for markerless motion capture. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2021, 212, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentini, A.; Pianese, T. The relationships among stakeholders in the organization of men’s professional tennis events. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2011, 3, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchik, S. Why Tennis Is Still Not Ready to Play Moneyball. Harv. Data Sci. Rev. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliopoulos, L. Randomization and serial dependence in professional tennis matches: Do strategic considerations, player rankings and match characteristics matter? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2018, 13, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Rosen, J.; Rust, J.; Wong, K.-P. Disequilibrium play in tennis. J. Polit. Econ. 2025, 133, 190–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Naikar, R. Predicting tennis serve directions with machine learning. In Machine Learning and Data Mining for Sports Analytics; Brefeld, U., Davis, J., Van Haaren, J., Zimmermann, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gourgari, S.; Goudelis, G.; Karpouzis, K.; Kollias, S. THETIS: Three dimensional tennis shots, a human action dataset. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Portland, OR, USA, 23–28 June 2013; pp. 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wang, J. Tennis serve recognition based on bidirectional long- and short-term memory neural networks. Mol. Cell. Biomech. 2025, 22, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Hossain, S.M.M.; Uddin, R.M.A.; Deb, K.; Jo, K.-H. Sequence recognition of indoor tennis actions using transfer learning and long short-term memory. In Frontiers of Computer Vision; Sumi, K., Na, I.S., Kaneko, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 312–324. [Google Scholar]

- Vainstein, J.; Manera, J.F.; Negri, P.; Delrieux, C.; Maguitman, A. Modeling video activity with dynamic phrases and its application to action recognition in tennis videos. In Proceedings of the Progress in Pattern Recognition, Image Analysis, Computer Vision, and Applications, Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2–5 November 2014; Bayro-Corrochano, E., Hancock, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 909–916. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, S.V.; Knottenbelt, W.J. Deep learning for domain-specific action recognition in tennis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Hu, J.; Tang, X.; Hung, T.-Y.; Tan, Y.-P. Deep historical long short-term memory network for action recognition. Neurocomputing 2020, 407, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Khan, J. Hybrid LSTM and GAN model for action recognition and prediction of lawn tennis sport activities. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 18093–18112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabaren, A. Tennis Serve Classification Using Machine Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Lucey, P.; Morgan, S.; Carr, P.; Reid, M.; Sridharan, S. Predicting serves in tennis using style priors. In Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 10–13 August 2015; pp. 2207–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, D.; Reid, M. Spatial characteristics of professional tennis serves with implications for serving aces: A machine learning approach. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tea, P.; Swartz, T. The analysis of serve decisions in tennis using Bayesian hierarchical models. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 325, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanaporn, S.; Kanongchaiyos, P.; Tangmanee, C. Using motion capture for analysis struggle of judo. In Proceedings of the IEEE CVPR Workshops, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–18 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Noiumkar, S.; Tirakoat, S. Use of optical motion capture in sports science: A case study of golf swing. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Informatics and Creative Multimedia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4–6 September 2013; pp. 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.; Whiteside, D.; Elliott, B. Effect of skill decomposition on racket and ball kinematics of the elite junior tennis serve. Sports Biomech. 2010, 9, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheze, L. Biomécanique du mouvement et modélisation musculo-squelettique. Technol. Bioméd. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; O’Sullivan, P.; Straker, L.; Elliott, B.; Reid, M. Back pain in tennis players: A link with lumbar serve kinematics and range of motion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, B.; Fleisig, G.; Nicholls, R.; Escamilia, R. Technique effects on upper limb loading in the tennis serve. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2003, 6, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skublewska-Paszkowska, M.; Powroznik, P.; Lukasik, E. Learning three-dimensional tennis shots using graph convolutional networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skublewska-Paszkowska, M.; Powroznik, P.; Lukasik, E. Attention temporal graph convolutional network for tennis groundstrokes phases classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skublewska-Paszkowska, M.; Powroznik, P. Temporal pattern attention for multivariate time series of tennis strokes classification. Sensors 2023, 23, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, G.D.; Harris, A.H.; Andriacchi, T.P.; Safran, M.R. Biomechanical analysis of three tennis serve types using a markerless system. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, G.D.; Sheets, A.L.; Andriacchi, T.P. Review of tennis serve motion analysis and the biomechanics of three serve types with implications for injury. Sports Biomech. 2011, 10, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, N.; Choppin, S.; Goodwill, S.R.; Allen, T. Markerless Tracking of Tennis Racket Motion Using a Camera. Procedia Eng. 2014, 72, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerson, J.; Needham, L.; Evans, M.; Williams, S.; Colyer, S. Comparison of markerless and marker-based motion capture for estimating external mechanical work in tennis: A pilot study. ISBS Proc. Arch. 2023, 41, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, F.; Lázaro, J.; Guzmán, J.F.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Crespo, M. Optimizing Sporting Actions Effectiveness: A Machine Learning Approach to Uncover Key Variables in the Men’s Professional Doubles Tennis Serve. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Zhu, R.; Ma, J.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Wen, J. Comprehensive Tennis Serve Training System Based on Local Attention-Based CNN Model. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 11917–11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, Q.; Jiang, W. Hybrid deep learning models for tennis action recognition: Enhancing professional training through CNN-BiLSTM integration. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2025, 37, e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamy, A.; Kreinovich, V.; Kosheleva, O. Why 70/30 or 80/20 Relation Between Training and Testing Sets: A Pedagogical Explanation. 2018. Available online: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/cs_techrep/1209/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, F.; Wang, J.; Sun, W. A Comparative Study on the Influence of Different Prediction Models on the Performance of Residual-based Monitoring Methods. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2022, 51, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, J. A Dual-Layer Attention-Based LSTM Network for Fed-batch Fermentation Process Modelling. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2021, 50, 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, C.-L. Chapter 11—Deep learning in biomedical informatics. In Intelligent Nanotechnology; Merging Nanoscience and Artificial Intelligence Materials Today; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Ke, R.; Pu, Z.; Wang, Y. Stacked Bidirectional and Unidirectional LSTM Recurrent Neural Network for Forecasting Network-Wide Traffic State with Missing Values. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 118, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A.; Jaitly, N.; Mohamed, A. Hybrid Speech Recognition with Deep Bidirectional LSTM. Proc. IEEE ASRU 2013, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessert, N.; Bengs, M.; Schlüter, M.; Schlaefer, A. Deep learning with 4D spatio-temporal data representations for OCT-based force estimation. Med. Image Anal. 2020, 64, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: An overview and application in radiology. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Haffner, P.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y. Object recognition with gradient-based learning. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 1999, 1681, 319–345. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | In | Out | Net | Excluded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 115 | 42 | 15 | 3 |

| 2 | 112 | 44 | 16 | 3 |

| Total | 227 | 86 | 31 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Durlind, G.; Martinez-Hernandez, U.; Assaf, T. Exploratory Proof-of-Concept: Predicting the Outcome of Tennis Serves Using Motion Capture and Deep Learning. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040118

Durlind G, Martinez-Hernandez U, Assaf T. Exploratory Proof-of-Concept: Predicting the Outcome of Tennis Serves Using Motion Capture and Deep Learning. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. 2025; 7(4):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040118

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurlind, Gustav, Uriel Martinez-Hernandez, and Tareq Assaf. 2025. "Exploratory Proof-of-Concept: Predicting the Outcome of Tennis Serves Using Motion Capture and Deep Learning" Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 7, no. 4: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040118

APA StyleDurlind, G., Martinez-Hernandez, U., & Assaf, T. (2025). Exploratory Proof-of-Concept: Predicting the Outcome of Tennis Serves Using Motion Capture and Deep Learning. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 7(4), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/make7040118