Ni-Co Nanoparticles@Ni3S2/Co9S8 Heterostructure Nanowire Arrays for Efficient Bifunctional Overall Water Splitting

Abstract

1. Introduction

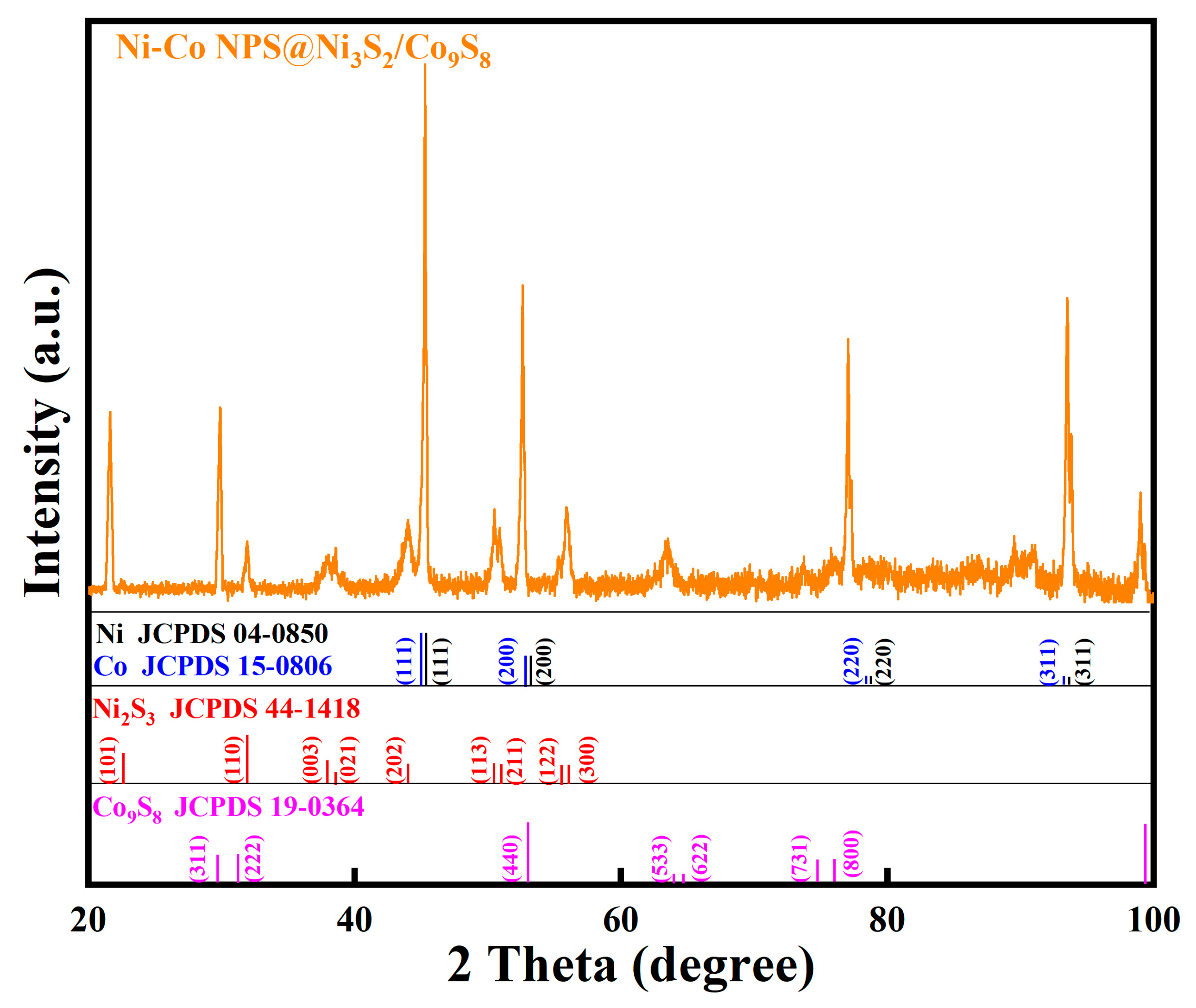

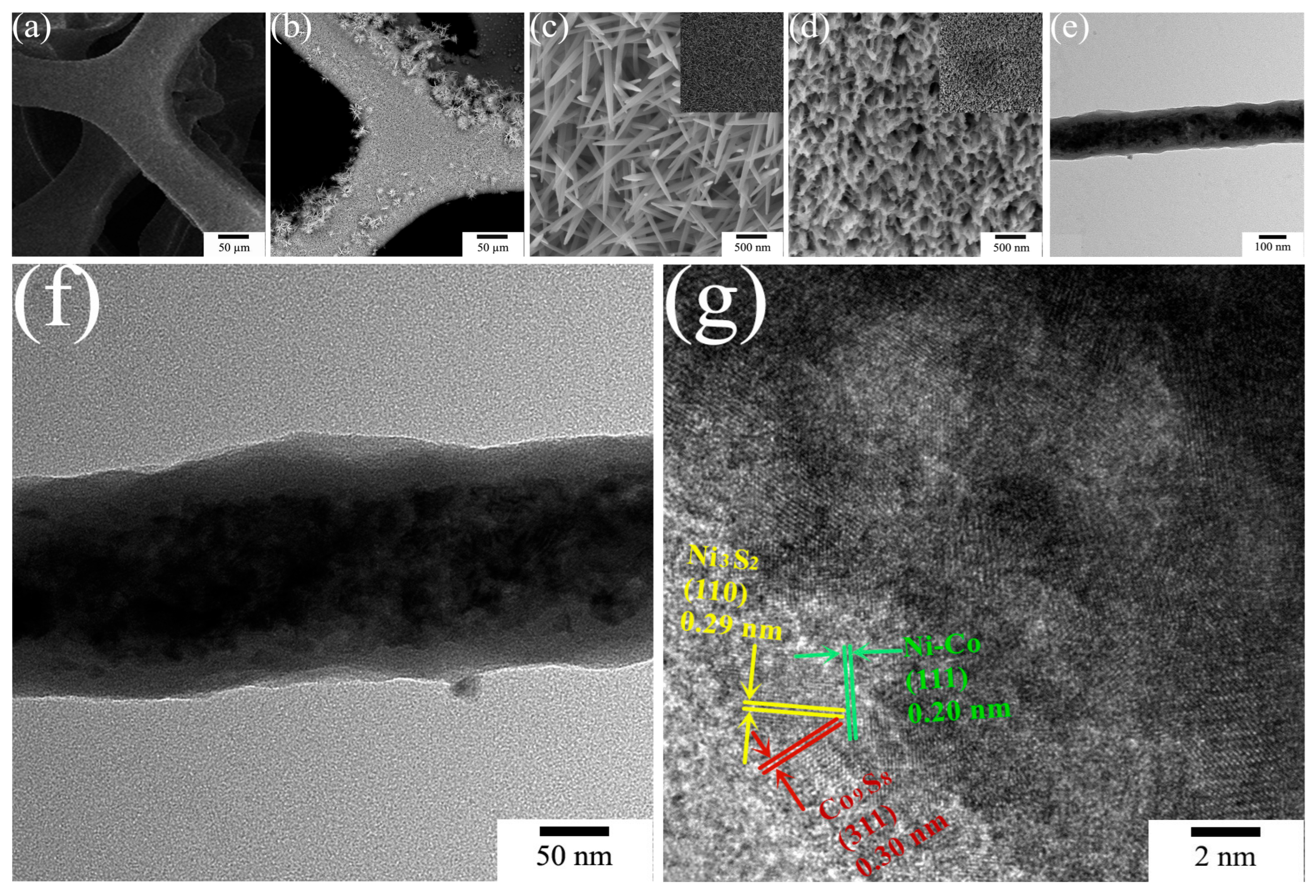

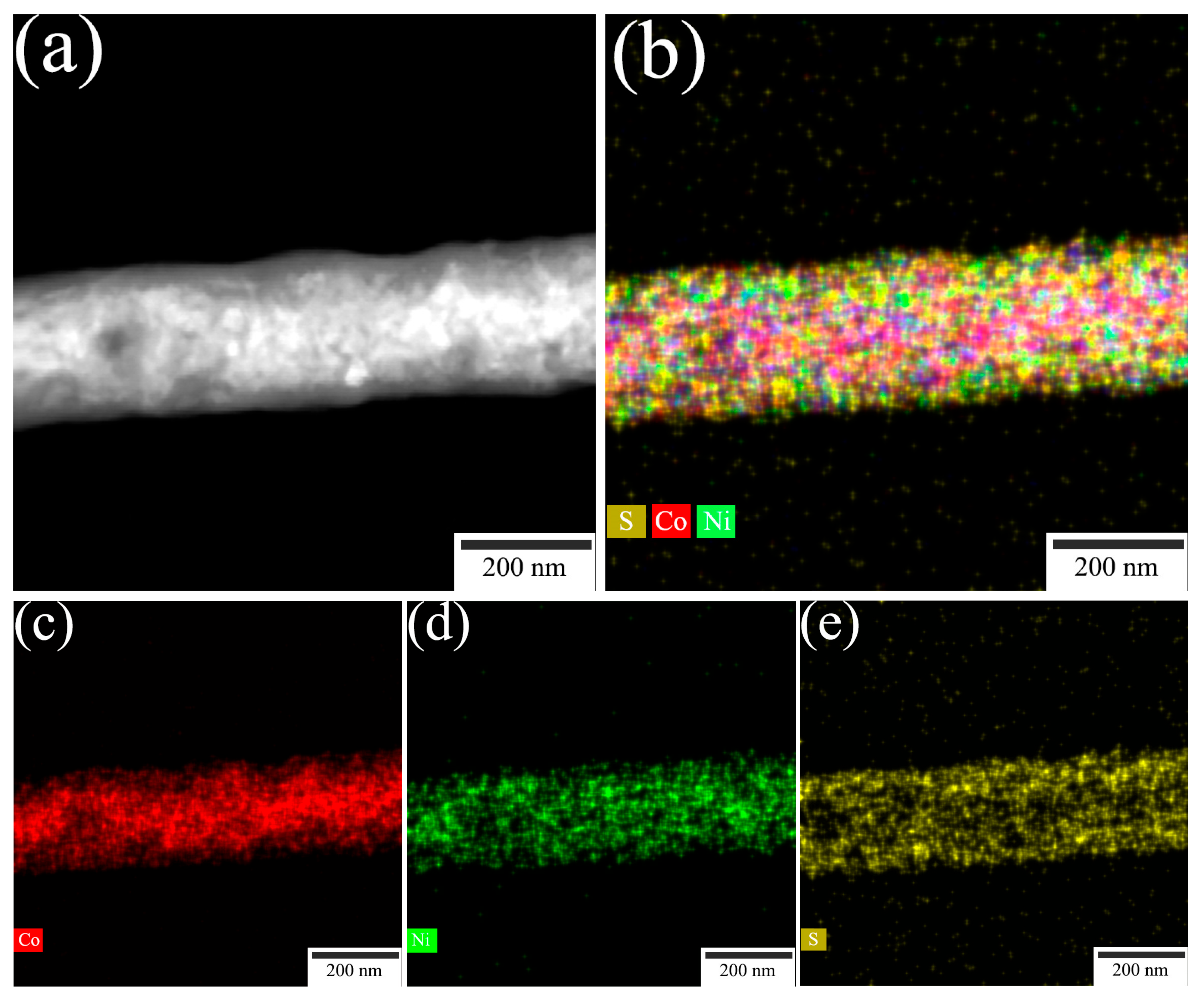

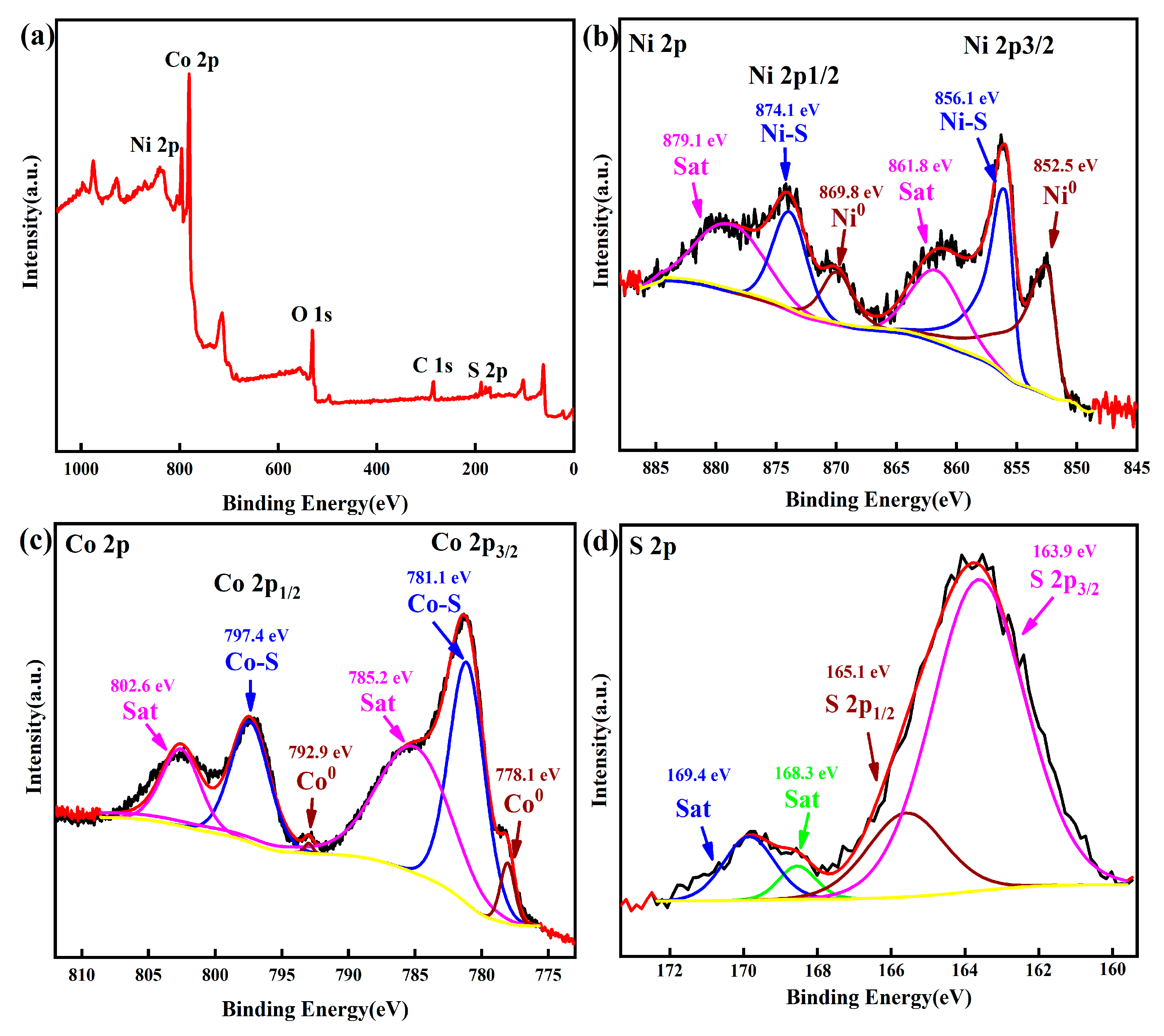

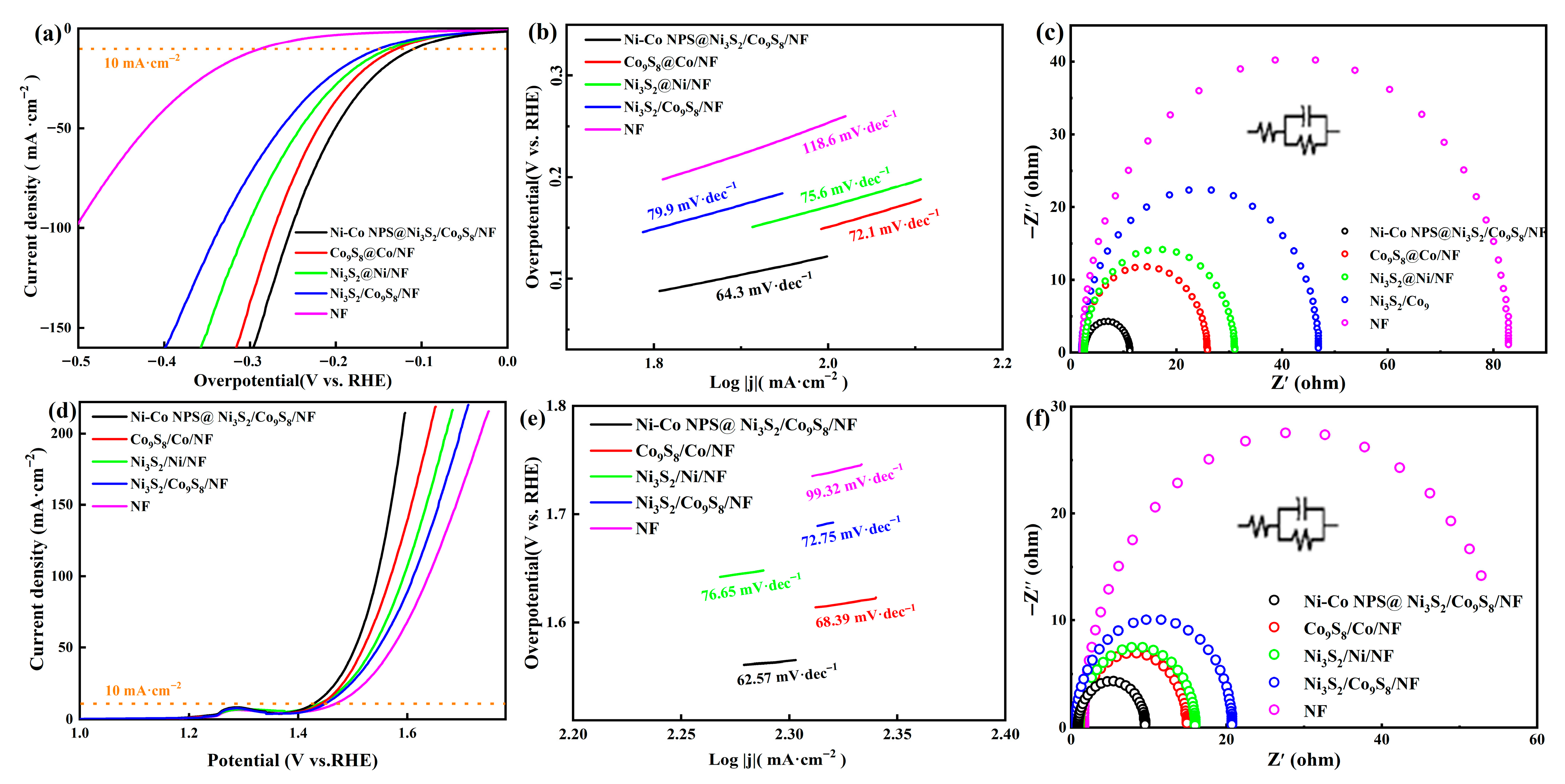

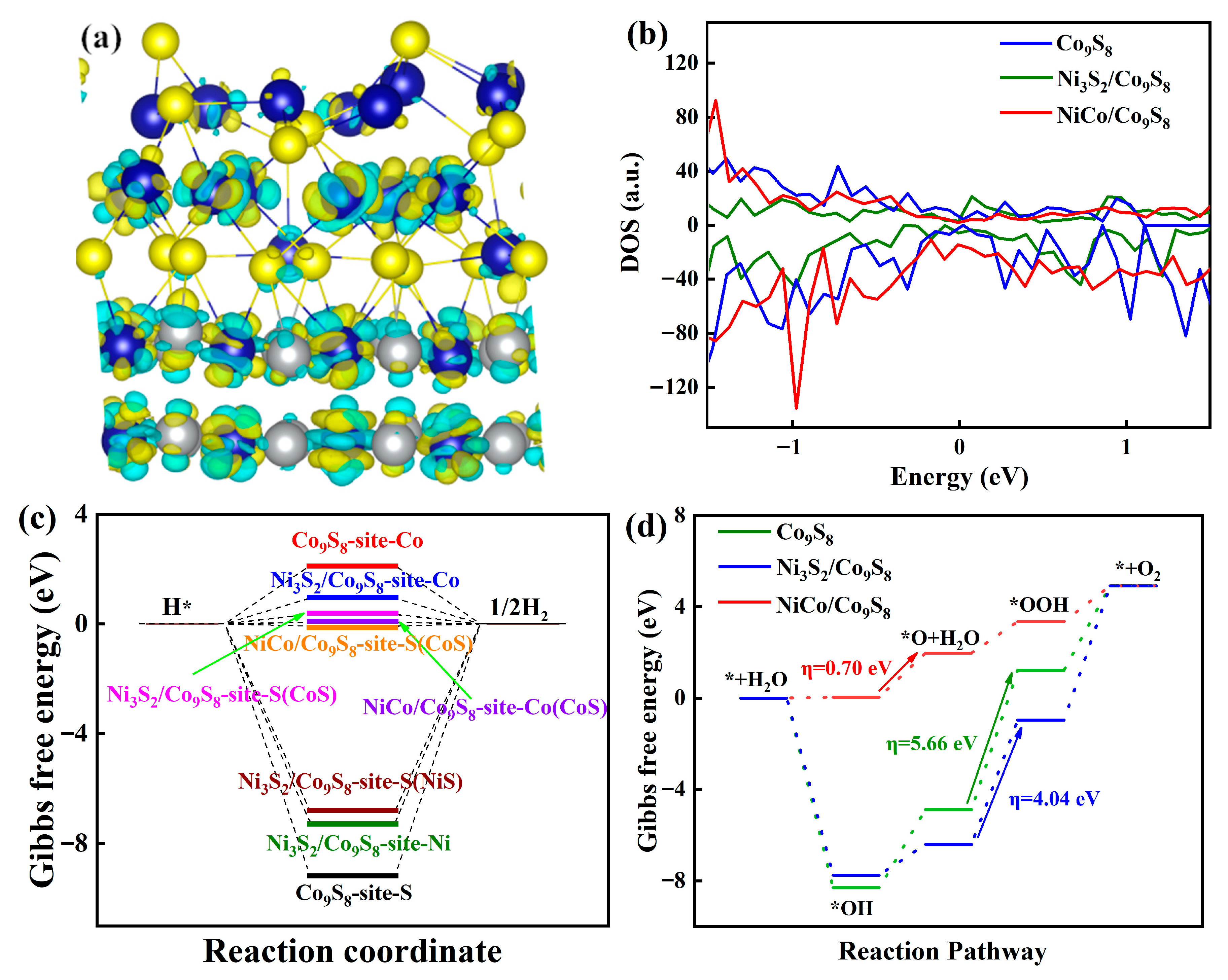

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rezayeenik, M.; Mousavi-Kamazani, M.; Zinatloo-Ajabshir, S. CeVO4/rGO nanocomposite: Facile hydrothermal synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical hydrogen storage. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnarabijia, M.S.; Tantawib, O.; Ramlic, A.; Zabidic, N.A.M.; Ghanema, O.B.; Abdullah, B. Comprehensive review of structured binary Ni-NiO catalyst: Synthesis, characterization and applications. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2019, 114, 109326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.K.; Zheng, Y.; Li, S.Q.; Su, H.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J.; Shu, H.B.; Jaroniec, M.; Chen, P.; Liu, Q.H. Nickel ferrocyanide as a high-performance urea oxidation electrocatalyst. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bai, X.; Jin, H.; Gao, X.; Davey, K.; Zheng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Qiao, S.Z. Directed urea-to-nitrite electrooxidation via tuning intermediate adsorption on CoGeCodoped Ni sites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2300687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yu, L.; Mishra, I.K.; Yu, Y.; Ren, Z.F.; Zhou, H.Q. Recent developments in earth-abundant and non-noble electrocatalysts for water electrolysis. Mater. Today Phys. 2018, 7, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.S.; Jin, S. Earth-abundant inorganic electrocatalysts and their nanostructures for energy conversion applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3519–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, M.; Tong, Y.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Xie, Y. 3D Nitrogen Anion decorated Nickel Sulfides for highly efficient overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, K.; Guo, L.; Marcus, K.; Li, Z.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Ye, R.; Orlovskaya, N.; Sohn, Y.H.; Yang, Y. Strained W(SexS1-x)2 nanoporous films for high efficient hydrogen evolution. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1315–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, W. High-performance and durable Pd5P2/PdP2 heterointerface for all-pH hydrogen evolution reactions. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 9413–9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Zhu, S.; Zeng, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Cao, D. Amorphous/crystalline Rh(OH)3/CoP heterostructure with hydrophilicity/aerophobicity feature for all-pH hydrogen evolution reactions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2302376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, X.X.; Yu, S.J.; Wen, T.; Zhu, X.W.; Yang, F.X.; Sun, X.N.; Wang, X.K.; Hu, W.P. Ternary NiCo2Px nanowires as pH-universal electrocatalysts for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; Ni, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, R.; Deng, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Tan, B.; Fang, Y. An efficient pH-universal non-noble hydrogen-evolving electrocatalyst from transition metal phosphides-based heterostructures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 31101–31109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Liu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; et al. Optimizing hydrogen binding on Ru sites with RuCo alloy nanosheets for efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202113664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, B.; Lin, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, L.; Fang, B.; Guo, S.; et al. PtSe2/Pt heterointerface with reduced coordination for boosted hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 23388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Han, H.; Je, M.; Choi, H.; Kwon, J.; Park, K.; Indra, A.; Kim, K.M.; Paik, U.; Song, T. Chemical and structural engineering of transition metal boride towards excellent and sustainable hydrogen evolution reaction. Nano Energy 2020, 67, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, D.; Liu, C.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, N.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. A review of covalent organic frameworks for metal ion fluorescence sensing. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Luo, M.; Chu, S.; Peng, M.; Liu, B.; Wu, Q.; Liu, P.; Groot, F.M.F.D.; Tan, Y. 3D nanoporous iridium-based alloy microwires for efficient oxygen evolution in acidic media. Nano Energy 2019, 59, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, D.; Zhang, S.; Yang, A.; Li, L.; Cai, Q.; Grimes, C.A.; Liu, Y. A PEDOT enhanced covalent organic framework (COF) fluorescent probe for in vivo detection and imaging of Fe3+. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Yu, L.; Wu, H.B.; Yu, X.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Lou, X.W. Formation of nickel cobalt sulfide ball-in-ball hollow spheres with enhanced electrochemical pseudocapacitive properties. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, J.; Li, P.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, P.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhang, E.; Sun, W.; Dou, S. Dual-atom support boosts Nickel-catalyzed urea electrooxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 135, e202217449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yin, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M.; Peng, Y.; Xi, P.; Yan, C. Atomic sulfur filling oxygen vacancies optimizes H absorption and boosts the hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 133, 14236–14242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhu, S.; Hao, Y.; Chang, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, J.; Chen, H.; Shao, M.; Peng, S. Modulating local interfacial bonding environment of heterostructures for energy-saving hydrogen production at high current densities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2212811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L. Progress in hydrogen production coupled with electrochemical oxidation of small molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 134, e202213328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Luo, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, T. High performance NiMoO4 nanowires supported on Carbon cloth as advanced electrodes for symmetric supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2014, 8, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zang, L.; Chu, M.; He, Y.; Ren, D.; Saha, P.; Cheng, Q. Oxygen-vacancy and Phosphorus-doping enriched NiMoO4 nanoarrays for high-energy supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, F.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Wen, G.; Alsaed, A.; Hayat, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, Z. Foam-like Co9S8/Ni3S2 heterostructure nanowire arrays for efficient bifunctional overall water-splitting. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 253, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.B.; Guo, Y.; Na, J.; Tahawy, R.; Chikyow, T.; El-Said, W.A.; El-Hady, D.A.; Alshitari, W.; Yamauchi, Y.; Lin, J. Layer-by-Layer motif heteroarchitecturing of N and S co-doped reduced graphene oxide-wrapped Ni/NiS nanoparticles for the electrochemical oxidation of water. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 3269–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.B.; Li, C.; Ji, Q.; Jiang, B.; Tominaka, S.; Ide, Y.; Hill, J.P.; Ariga, K.; Yamauchi, Y. Self-Construction from 2D to 3D: One-pot layer-by-layer assembly of graphene oxide sheets heldtogether by coordination polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8426–8430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.B.; Malgras, V.; Takei, T.; Li, C.; Yamauchi, Y. Layer-by-Layer motif hybridization: Nanoporous nickel oxide flakes wrapped into graphene oxide sheets toward enhanced oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 16409–16412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shi, J.; Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Liu, S.; Li, C. Quasi-Amorphous metallic Nickel nanopowder as an efficient and durable electrocatalyst for alkaline hydrogen evolution. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1801216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.B.; Tan, H.; Kim, J.; Badjah, A.Y.; Naushad, M.; Habila, M.; Wabaidur, S.; Alothman, Z.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Lin, J. Structurally controlled layered Ni3C/graphene hybrids using cyano-bridged coordination polymers. Electrochem. Commun. 2019, 100, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.B.; Ebeid, E.Z.M.; Abdel-Galeil, M.M.; Chikyow, T. Cyanide bridged coordination polymer nanoflakes thermally derived Ni3C and fcc-Ni nanoparticles for electrocatalysts. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 14890–14897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, K.; Li, L.; Wei, X.; Cai, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, R.; Wei, F.; Lan, B.; et al. One-pot synthesis of Ni-Co nanoparticles@Ni0.19Co0.26P nanowires core/shell arrays on Ni foam for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction at all pH values. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 111002, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, G.; Peng, F.; Yu, H. Co3S4/NCNTs: A catalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Catal. Today 2015, 245, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Tang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. Three-dimensional well-mixed/highly-densed NiS-CoS nanorod arrays: An efficient and stable bifunctional electrocatalyst for hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 260, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Zhang, L.; Hsu, C.W.; Chuan, X.F.; Lu, S.Y. Mixed NiO/NiCo2O4 nanocrystals grown from the skeleton of a 3D porous Nickel network as efficient electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution Reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018, 10, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Peng, J.; Peng, K. Bifunctional NiCo2O4 porous nanotubes electrocatalyst for overall water-splitting. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 318, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, F.; Yu, X.; Kang, W.; Zhang, J. One-step synthesis of Co9S8@Ni3S2 heterostructure for enhanced electrochemical performance as sodium ion battery anode material and hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst. J. Solid State Chem. 2020, 285, 121230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, F.Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.B.; He, H.L.; Huang, X.F.; Fan, X.; Zhang, X.M. (003)-Facet -exposed Ni3S2 nanoporous thin films on nickel foil for efficient water splitting. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2019, 243, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, P.; Yan, X.; Gu, L.; Yang, Z.; Yang, H.; Qiu, S.; Yao, X. Atomically isolated nickel species anchored on graphitized carbon for efficient hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Li, P.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, G.; Chen, S.; Luo, W. Tailoring the electronic structure of Co2P by N do** for boosting hydrogen evolution reaction at all pH values. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3744–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tong, R.; Wang, Y.; Tao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H. Surface roughening of Nickel Cobalt Phosphide nanowire arrays/Ni foam for enhanced hydrogen evolution activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2016, 8, 34270–34279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Liang, Y.; Wu, J.Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Regier, T.; Wei, F.; Dai, H. An advanced Ni-Fe layered double hydroxide electrocatalyst for water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8452–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsounaros, I.; Cherevko, S.; Zeradjanin, A.R.; Mayrhofer, K.J. Oxygen electrochemistry as a cornerstone for sustainable energy conversion. Angew. Chem. 2014, 53, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, E.; Habereder, A.; Waltar, K.; Kötz, R.; Schmidt, T.J. Developments and perspectives of oxide-based catalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 3800–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, L.; Han, Y.; Chen, Y.; Du, A.; Jaroniec, M.; Qiao, S. Hydrogen evolution by a metal-free electrocatalyst. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greeley, J.; Bonde, J.; Chorkendorff, I.; Norskov, J. Computational high-throughput screening of electrocatalytic materials for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, I.; Su, H.; Calle-Vallejo, F.; Hansen, H.; Martínez, J.; Kitchin, J.; Jaramillo, T.; Nørskov, J.; Rossmeisl, J. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem. 2011, 3, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Dong, C.; Ma, J.; Shen, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Filling the oxygen vacancies in Co3O4 with phosphorus: An ultra-efficient electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2563–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Jiang, Z. In-situ single-phase derived NiCoP/CoP hetero-nanoparticles on aminated-carbon nanotubes as highly efficient pH-universal electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 416, 140280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Song, Y.; Gong, X.; Cao, L.; Yang, J. An efficiently tuned d-orbital occupation of IrO2 by doping with Cu for enhancing the oxygen evolution reaction activity. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 4993–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Chi, W.; Qin, A.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhong, Z.; Xie, X.; He, W.; Jin, M.; et al. Ni-Co Nanoparticles@Ni3S2/Co9S8 Heterostructure Nanowire Arrays for Efficient Bifunctional Overall Water Splitting. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120657

Zhang L, Chi W, Qin A, Liu F, Wang Y, Wang H, Zhong Z, Xie X, He W, Jin M, et al. Ni-Co Nanoparticles@Ni3S2/Co9S8 Heterostructure Nanowire Arrays for Efficient Bifunctional Overall Water Splitting. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):657. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120657

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lei, Wenwen Chi, Ao Qin, Fojian Liu, Yanhui Wang, Huimei Wang, Ziyi Zhong, Xinyi Xie, Wenmei He, Meiyan Jin, and et al. 2025. "Ni-Co Nanoparticles@Ni3S2/Co9S8 Heterostructure Nanowire Arrays for Efficient Bifunctional Overall Water Splitting" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120657

APA StyleZhang, L., Chi, W., Qin, A., Liu, F., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Zhong, Z., Xie, X., He, W., Jin, M., Li, Y., Zhang, F., & Liang, H. (2025). Ni-Co Nanoparticles@Ni3S2/Co9S8 Heterostructure Nanowire Arrays for Efficient Bifunctional Overall Water Splitting. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120657