1. Introduction

The reconstruction of lip defects presents a significant challenge in maxillofacial surgery due to the complex functional and aesthetic requirements of the perioral region. The lips play a crucial role in various essential functions, including speech articulation, facial expression, oral competence, and maintaining oral hygiene [

1,

2]. Additionally, they are central to facial aesthetics and social interaction, making their reconstruction particularly demanding in terms of both form and function [

3].

Traditional approaches to lip reconstruction have included various local and regional flaps, such as the Abbe flap, Estlander flap, and nasolabial flaps [

1,

2]. While these techniques have proven effective for certain defects, they often result in additional scarring. They may not adequately address volume deficiencies, particularly in partial-thickness defects or post-tumor resection deformities [

3,

4]. Furthermore, these conventional approaches frequently require multiple surgical stages and can lead to significant donor site morbidity.

The buccal fat pad (BFP) has emerged as a versatile and valuable tissue source in maxillofacial reconstruction. Historically, it has been successfully employed in various applications, including the closure of primary clefts, treatment of oral submucous fibrosis, and improvement of upper lip profile in orthognathic patients [

5,

6,

7]. Its use has extended to more complex procedures, such as the repair of skull base defects following tumor resection and the prevention of Frey’s syndrome after parotidectomy [

8,

9]. The success of BFP in these applications can be attributed to its rich vascularity, easy accessibility, and minimal donor-site morbidity [

5,

6].

The traditional application of BFP has primarily been as a pedicled flap, with its reach limited to the region extending from the angle of the mouth to the retromolar trigone and the palate [

5,

6]. This anatomical constraint has historically restricted its broader application in facial reconstruction. However, recent developments have shown promising results in using BFP as a free graft material, particularly in temporomandibular joint reconstruction and vocal cord augmentation [

7].

Structural fat grafting has become increasingly popular in the broader context of maxillofacial volumetric reconstruction [

1]. This technique typically involves harvesting autologous fat from various donor sites, such as the abdomen or thighs, processing it, and carefully injecting it into the recipient site [

1,

2]. While effective, this approach often requires multiple sessions to achieve the desired volume and may result in unpredictable resorption rates [

3,

4].

Recently, we have begun exploring an innovative approach using BFP as a free graft specifically for lip reconstruction. This application represents a significant departure from its traditional use as a pedicled flap and offers several potential advantages over conventional fat grafting techniques [

10,

11]. The proximity of the donor site, the unique biological properties of buccal fat, and the possibility of achieving predictable results in a single surgical session make this approach particularly promising for addressing lip deformities resulting from trauma or tumor resection.

This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of BFP-free grafts in lip reconstruction through a series of cases, examining both the technical aspects of the procedure and its outcomes. We present our experience with this novel application, including surgical technique, postoperative course, and short-term and long-term results. Furthermore, we discuss the advantages and limitations of this approach compared to traditional reconstruction methods, with particular attention to functional and aesthetic outcomes [

10,

11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

This study was conducted at the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Unit at Shaare-Zedek Medical Centre, Jerusalem, Israel. We included five patients who presented with various lip defects requiring reconstruction. The pathologies included vascular malformations, benign and malignant tumors, and trauma-induced defects. Each patient underwent thorough preoperative imaging appropriate to their condition, including sonography for superficial masses, MRI for vascular lesions, and standard radiographs for trauma cases.

2.2. Surgical Technique

Buccal Fat Pad Harvesting

The surgical procedure was performed under general anesthesia and followed a consistent technique. For harvesting the buccal fat pad, we made a 2–3 cm incision in the upper maxillary vestibule, carefully positioned above the second molar and at least one centimeter below Stensen’s duct. Through gentle blunt dissection in a superior and disto-buccal direction, we exposed the characteristic yellow-colored fat pad through its capsule. The fat was then carefully herniated using downward traction with forceps until we obtained an adequate volume. After detaching the fat base, we preserved it in normal saline until use. We closed the vestibular incision with Vicryl 3/0 sutures (Johnson and Johonson Int., Diegem, Belgium) and confirmed the patency of Stensen’s duct through parotid gland milking.

2.3. Reconstruction Procedure

The reconstruction technique varied based on the timing of the procedure. We performed immediate reconstruction in benign lesions by transferring the harvested fat into a submucosal pouch created after mass excision. We made a surgical pouch in the lip defect area for cases requiring delayed reconstruction. In all cases, we secured the free fat graft within the submucosal region using 4/0 Vicryl sutures (Johnson and Johonson Int., Diegem, Belgium).

2.4. Follow-Up Protocol

We followed our patients’ progress through regular postoperative visits. The initial assessment focused on immediate postoperative changes, particularly edema and graft volume. Subsequent visits at 1–2 weeks allowed us to monitor the expected partial necrosis phase. By 4–5 weeks, we evaluated mucosal revascularization, and final assessments at 8–12 weeks focused on lip volume stability, function, and aesthetic outcomes. Throughout the follow-up period, we documented changes in lip symmetry, mucosal healing, functional recovery, and any complications.

2.5. Long-Term Follow-Up Assessment

Extended follow-up was conducted for all patients at least one year post-surgery. During these visits, we assessed graft volume stability and maintenance, long-term aesthetic outcomes, functional preservation, patient satisfaction, and any signs of volume regression or complications. Special attention was paid to the vermilion border integrity and overall lip contour preservation.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted with the approval of Shaare-Zedek Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board (approval number: 0173-22-SZMC) and followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients or their legal guardians provided written informed consent for both the surgical procedure and the publication of their clinical information and images.

3. Results

Case 1:

An 8-year-old female had a 10 × 10 mm mass just above the vermilion border of the right upper lip (

Figure 1A). The mass was asymptomatic and protruded on both aspects of the lip (buccal mucosa and skin). Sonography detected a solid hypoechoic mass with a well-defined border and vigorous vascularity at the margins. The lesion, which was attached to the skin, was excised under general anesthesia, resulting in a full-thickness defect and significant volume loss. The free fat graft was harvested from the buccal pad (

Figure 1B). The fat was used for lip volumetric restoration (

Figure 1C).

The pathological diagnosis of the excised mass was compatible with solitary juvenile Xanthogranuloma.

Case 2:

A 32-year-old female with a 10 mm diameter vascular lesion on the right lower lip (

Figure 2A). MRI demonstrated a hyperintense and well-defined submucosal lesion (Arrow in

Figure 2B). The findings were consistent with cavernous venous malformation. The lesion was resected under general anesthesia, creating a volumetric defect of the right lower lip that was restored using a free fat graft harvested from the buccal pad (

Figure 2C).

Case 3:

A 64-year-old female was diagnosed with a 5 × 7 mm venous malformation in the right lower lip (

Figure 3A), which irritated the patient, as it bled often and was disturbing in appearance (

Figure 3B). The lesion was resected, leaving a soft tissue defect reconstructed using a BFP-free graft (

Figure 3C).

Case 4:

A 55-year-old female with well-differentiated SCC and severe dysplasia of the right lower lip (

Figure 4A). The lesion was excised, and the dysplastic right lower lip mucosa was shaved. Immediate restoration of the vermilion mucosa was done using a local mucosal flap (

Figure 4B). The surgery resulted in significant lip asymmetry and volume reduction, leading to functional and aesthetic impairments (

Figure 4C). Three months later, a pouch was created on the right side of the lower lip to enable volume restoration with free graft harvested from the BFP (

Figure 4D). The lack of tension during primary closure was established by the vestibular horizontal incision parallel to the surgical incision (arrow in

Figure 4E).

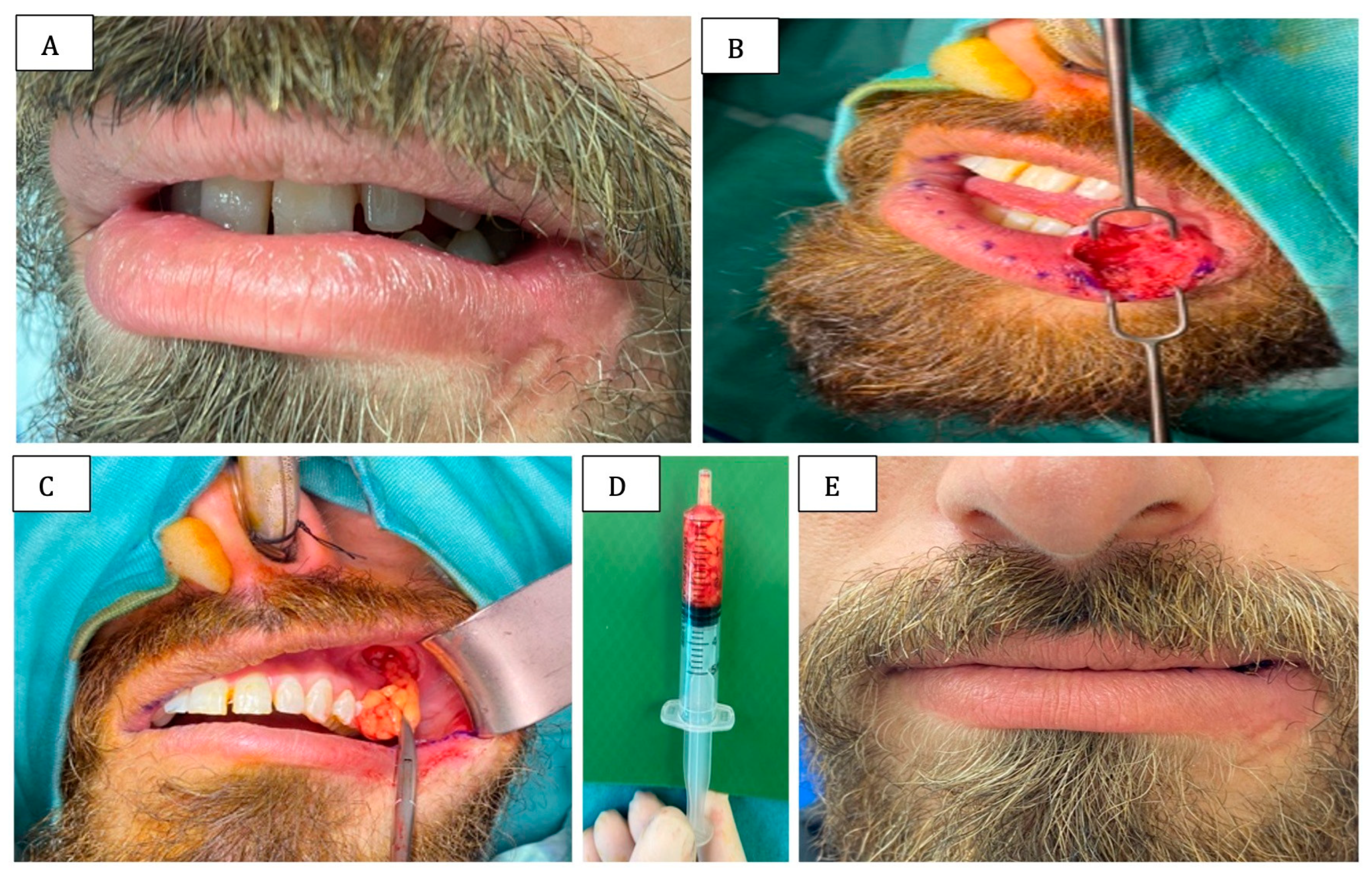

Case 5:

A 26-year-old male was injured in his lip and mandible by a rubber bullet. He suffered a left mandibular fracture and a soft tissue defect in the left lower lip. As a result, he had functional difficulties due to incompetent lips on the injured site (

Figure 5A). A pouch was created in the defected side (

Figure 5B), and free buccal fat was harvested and used for lip reconstruction (

Figure 5C,D).

Mucosal revascularization occurred over 4–5 weeks, and the final lip volume was obtained 8–12 weeks post-surgery with normal mucosal color, restoration of function, and sealing of the lips while eating and talking (

Figure 1F,

Figure 2F,

Figure 3E,

Figure 4G and

Figure 5E).

In case number 1, normal mucosal color was restored after 3 months, but there was still asymmetry, which may have resulted from the use of excessive fat graft or may be related to the patient’s young age and the possible differences in the characteristics of adipose tissue between young and adult patients. Additional surgical intervention to move the excess implanted fat or filler injection to the thinner side of the lip might be needed to correct the asymmetry (

Figure 1F).

All five patients underwent extended follow-up assessment at an average of 20 months post-surgery (range 12–24 months). Long-term evaluation demonstrated excellent graft stability with maintained lip volume and contour in all cases. No patients showed volume regression beyond the vermilion border, and the reconstructed lip segments preserved their functional and aesthetic properties.

4. Discussion

The practice of structural fat grafting has gained popularity in both aesthetic and reconstructive surgery due to its many advantages, including a high survival rate, biocompatibility, graft integration, reversibility of the outcome by a simple procedure of graft debridement, and the potential for long-term stability of outcome [

5,

8]. The success of our technique is partially attributed to the superior vascularization of the lip region. The lips possess a rich vascular network supplied by the labial arteries, creating an optimal recipient environment that facilitates rapid neovascularization and reduces graft necrosis risk compared to poorly vascularized areas.

In the realm of facial recontouring and enhancement, grafted fat has been used prominently in areas such as the zygoma, cheeks, nose, mandibular jawline, and lips [

1,

8,

9,

10]. The donor sites for fat harvesting include the trochanteric region, inner thighs and knees, the periumbilical area, and the flanks. Fat injection to the recipient site uses cannulas with varying tip shapes, diameters, lengths, and curves [

8].

One of the primary concerns with free fat grafting techniques is the unpredictable long-term resorption rate, which often necessitates multiple procedures to maintain desired outcomes [

8,

10]. Our extended follow-up data, averaging 20 months post-surgery, addresses this critical concern by demonstrating sustained volume maintenance in all patients. Unlike conventional fat grafting, where resorption rates can be significant and unpredictable, the BFP free graft showed remarkable stability with no volume regression beyond the vermilion border observed in any of our cases.

The BFP graft procedure, when used in its pedicled version, has shown a high success rate owing to its rich vascularity, proximity to the recipient site, the ability to reconstruct significant defects, low donor site morbidity, and the ease of the grafting procedure [

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

12]. However, the range of its application is limited. It correlates with the length of the pedicle, so it is unsuitable for reconstructing defects of the lower lip and mucosal defects in the mandibular symphyseal area.

Previously, bilateral pedicled buccal fat pads were used during orthognathic surgeries for upper lip augmentation [

6]. To expand the scope of usage, we introduce the free graft version of the BFP to recontour and restore the volume of both upper and lower lips.

Aside from expanding the usage range, free buccal fat pad grafting has numerous advantages over structural fat grafting. This includes the proximity of the donor and recipient sites, thus avoiding additional donor site morbidity and visible scars. It overcomes the problem of insufficient fat volume in lean patients and the challenge of achieving an acceptable result with a single procedure due to long-term stability. Furthermore, it has been found that the BFP contains twice the quantity of stem cells as compared to lipoaspirate fat. Such stem cells are located around the large vessels surrounding the fat cells and play an essential role in healing [

8,

11]. The volume of transplanted adipose tissue represents a critical factor in our outcomes. Lip reconstruction typically requires small volumes (1–3 mL), which falls within the optimal range for fat graft survival. Smaller volumes benefit from superior graft-to-vascular bed ratios, allowing efficient nutrient diffusion. However, volume prediction remains challenging, and our experience suggests initial over-grafting by 20–30% to compensate for expected resorption.

The stability of the BFP plays a positive role when used in multi-staged surgical treatments (e.g., in cases of tumor tissue removal) since it reduces the number of surgical interventions needed to get acceptable aesthetic and functional results.

Multi-staged surgical treatment is used for the reconstruction of lip defects after malignant tumor resection, which leads to aesthetic and functional malformations. Since free cancerous cell margins are needed before defect reconstruction, lip restoration is usually delayed as opposed to immediate restoration allowed after benign tumor resection.

In terms of fat tissue availability, the volume of fat needed for reconstructing the lip does not exceed 2 mL, which is not expected to cause any changes in the facial contour with aging. The BFP provides 2–4 mL of harvestable tissue per side, adequate for most lip reconstruction needs. The encapsulated nature and atraumatic harvest preserve cellular architecture, maximizing viable adipocytes and stem cells. Unlike lipoaspirate fat damaged by suction, BFP maintains structural integrity and predictable graft behavior.

However, there is a lack of information in the literature regarding the volume required for augmentation and the precise shrinkage rate of the free BFP graft. Future research should be conducted using preoperative and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging of the reconstructed region in order to obtain this information.

Based on the postoperative course and the follow-up of the described 5 cases, the stability of the graft is supported by its minimal shrinkage rate (

Figure 1F,

Figure 2F,

Figure 3E,

Figure 4G and

Figure 5E).

The lack of potential for submucosal pigmentation caused by BFP on the augmented site is attributed to tissue merging with the adjacent normal lip part (

Figure 1F,

Figure 2F,

Figure 3C,

Figure 4E and

Figure 5E).

Resiliency is also a feature of BFP grafts [

5,

6,

7], which plays a role in its long-term stability. However, based on our patients’ subjective complaints, it could also cause lip rigidity. The rigidity did not affect the function in all of the reported cases. Still, it contributed to better anterior lip sealing, thus preventing drawling and improving speech and swallowing in cases where late-stage defect reconstruction was performed (cases 3, 4, and 5). The microenvironmental conditions of the lip region provide unique advantages for graft integration. The oral cavity’s physiological conditions, mechanical stimulation from normal function, and rich stem cell niche create a supportive environment. Saliva exposure and absence of tissue tension when properly positioned contribute to enhanced healing and superior long-term stability.

Aside from the above-stated advantages of the free BFP graft procedure, there are also certain drawbacks, such as difficulty manipulating and retaining fat within the surgical bounded space while suturing the incisional site and potential fibrosis of the free graft. There is also concern about the exact fat volume needed for reconstruction and additional surgical interventions in case of post-recovery lip asymmetry, as in case 1.

Mucosal necrosis and subsequent healing have been previously documented in the literature as part of the normal healing process. Long-term necrosis can be avoided by ensuring that the stretched buccal fat-free graft used to cover defects does not exceed 4 cm. Otherwise, its vascularity could be compromised, resulting in dehiscence. Furthermore, the CD34 markers expressed by buccal fat pad-derived stem cells have been demonstrated to stimulate neovascularization and facilitate the healing of scarred and injured tissue [

10,

11].

All five reported cases had short-term necrosis as part of the immediate postoperative healing course. However, all had good neovascularity and a sound healing process, with no tissue necrosis observed during the long-term follow-up. (

Figure 1F,

Figure 2F,

Figure 3G,

Figure 4E and

Figure 5E). The mucosal necrosis observed in our cases during the first 1–2 weeks represents a normal phase of fat graft integration, where peripherally located adipocytes undergo predictable sacrifice due to initial avascular conditions. The superior outcomes observed with BFP free grafts can be attributed to the enhanced regenerative properties of buccal fat pad-derived adipose stem cells (ADSCs). Recent literature demonstrates that BFP contains twice the concentration of mesenchymal stem cells compared to conventional subcutaneous fat, with high levels of CD34+ markers associated with enhanced angiogenic potential. During healing, these ADSCs play crucial roles by differentiating into endothelial cells, secreting angiogenic factors including VEGF, and providing paracrine signaling that enhances tissue repair and neovascularization. This enhanced stem cell activity explains the excellent long-term stability and minimal resorption observed in our patients, distinguishing BFP free grafting from conventional fat transplantation techniques.

The exceptional outcomes result from synergistic interaction of multiple favorable factors: superior donor tissue quality, optimal recipient site characteristics, appropriate graft volumes, and favorable mechanical conditions. This multifactorial advantage distinguishes BFP free grafting from conventional techniques and explains the superior stability observed in our patients, despite its disadvantages, which are mainly related to difficulties in the planning (volume needed and shrinkage rate) and executive levels (manipulation and wound closure).

Limitations

Several limitations warrant consideration in interpreting our findings. The limited volume available for harvesting and the restricted dimensions of the reconstructed site represent inherent constraints of this technique. As a small case series of five patients, our study lacks the statistical power to detect rare complications or establish definitive superiority over conventional techniques. The absence of a control group limits our ability to make direct comparisons with alternative reconstruction methods. Additionally, while our extended follow-up provides valuable long-term data, longer observation periods would strengthen conclusions about the durability of these reconstructions. Finally, the technique requires specific anatomical expertise and careful patient selection, which may limit its broader applicability in routine clinical practice.