Effects of Process Parameters, Sheet Thickness and Adhesive on Spot Diameter During Resistance Spot Welding of Aluminum Alloys EN AW-5182 and EN AW-6005 †

Abstract

1. Introduction

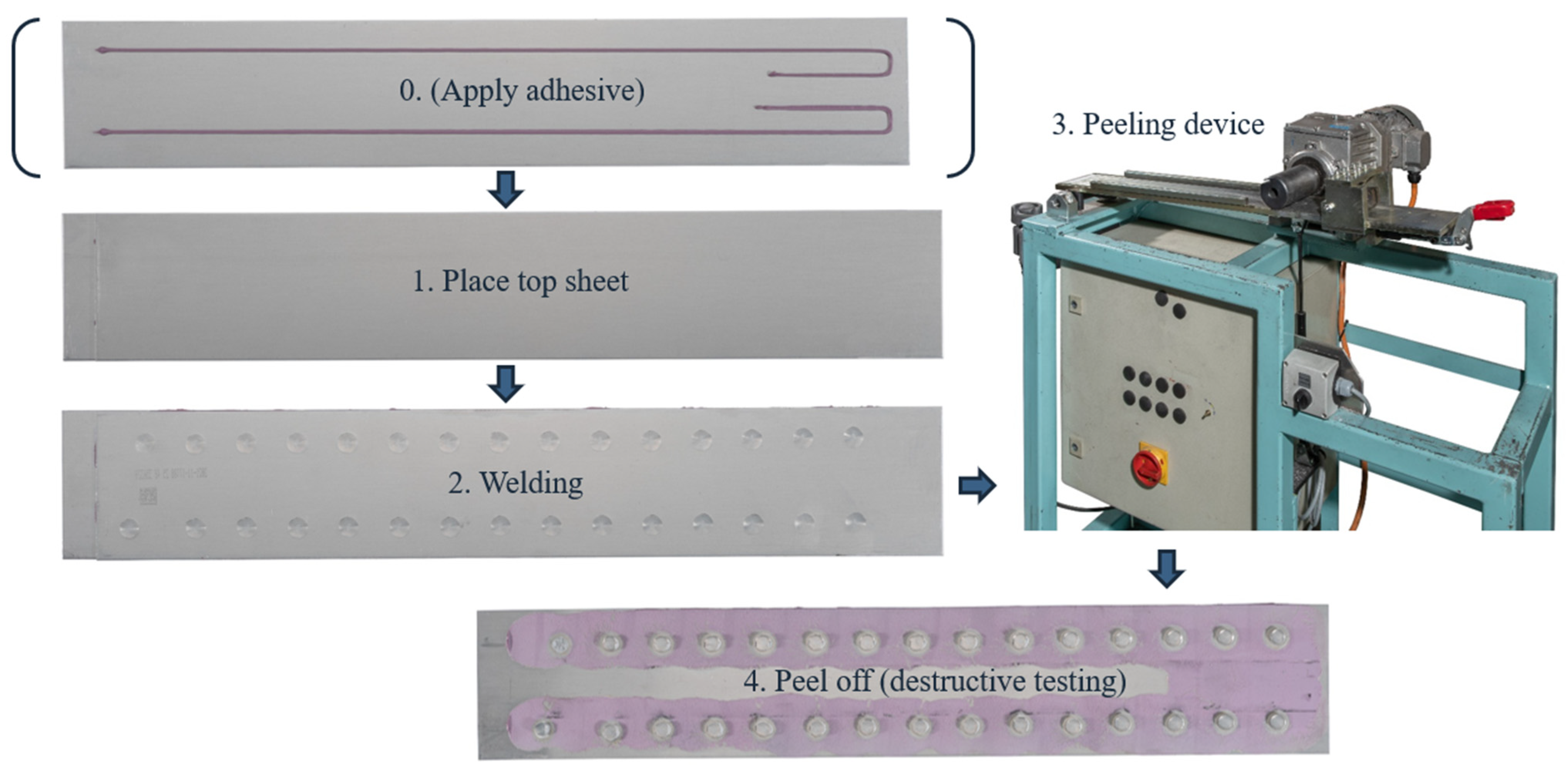

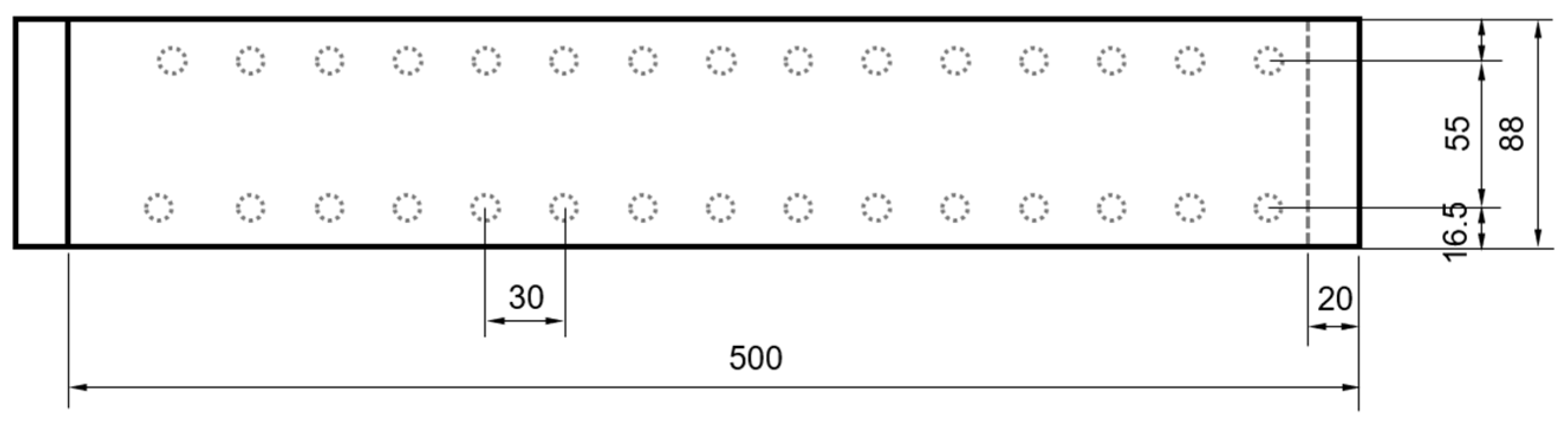

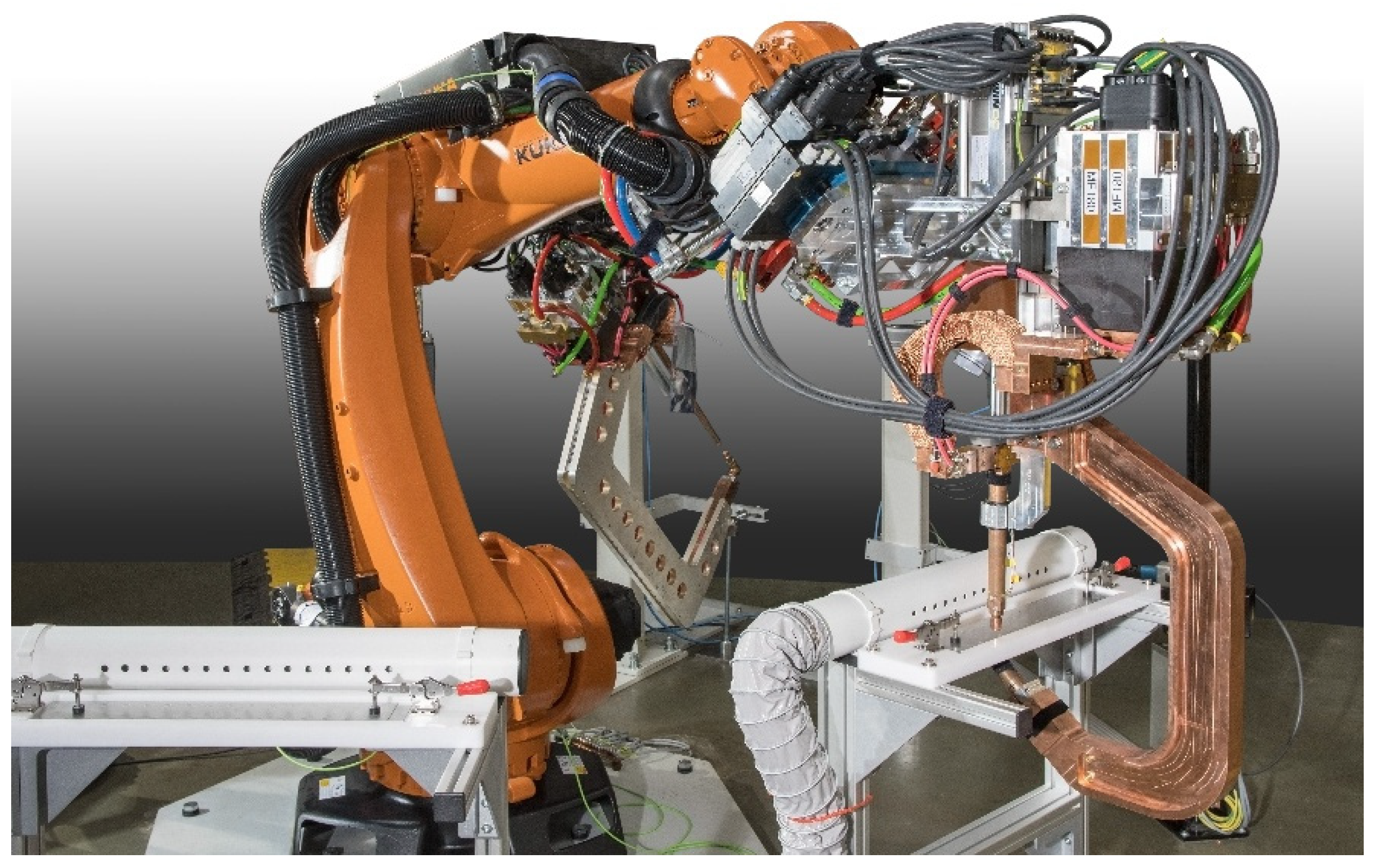

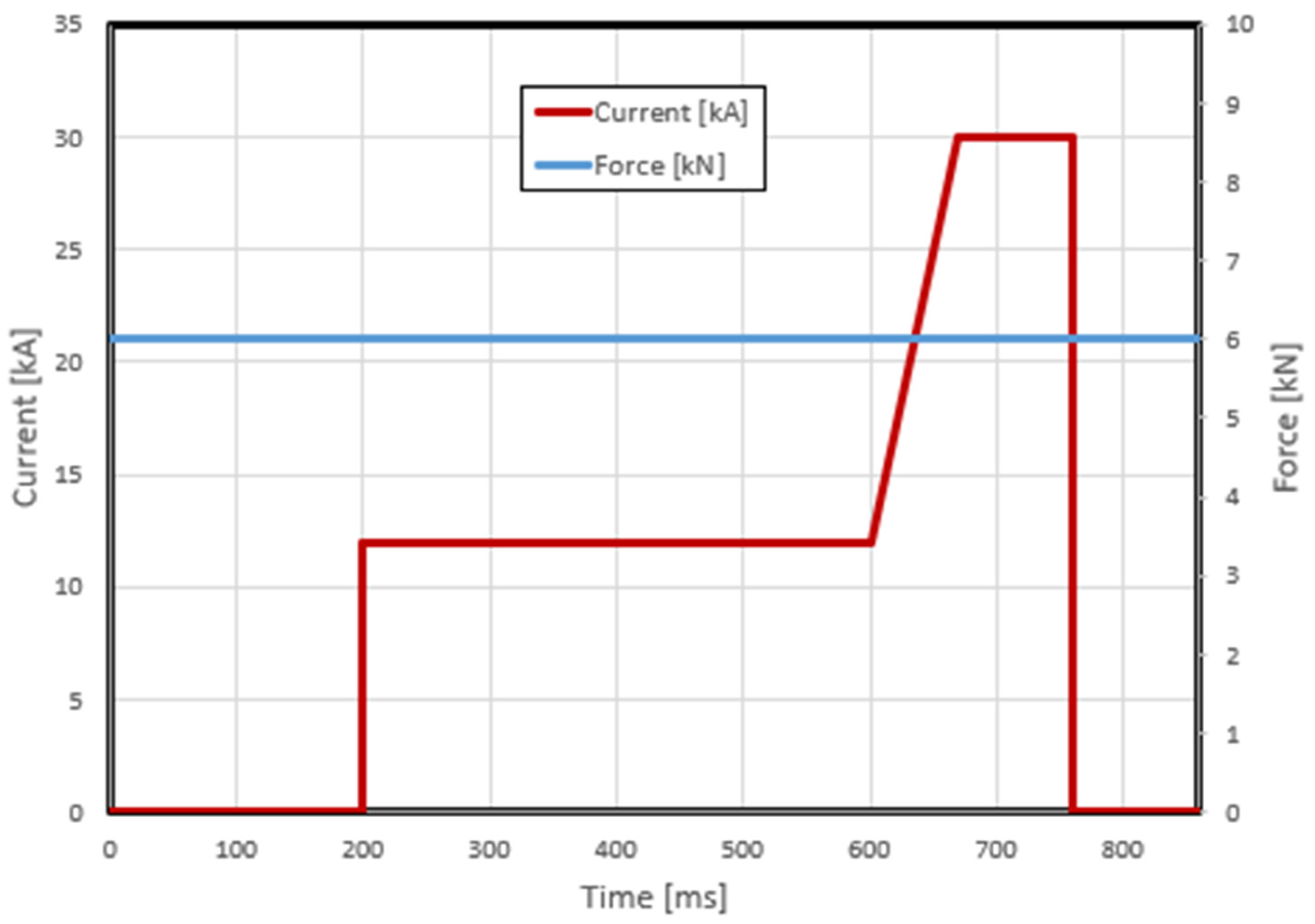

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

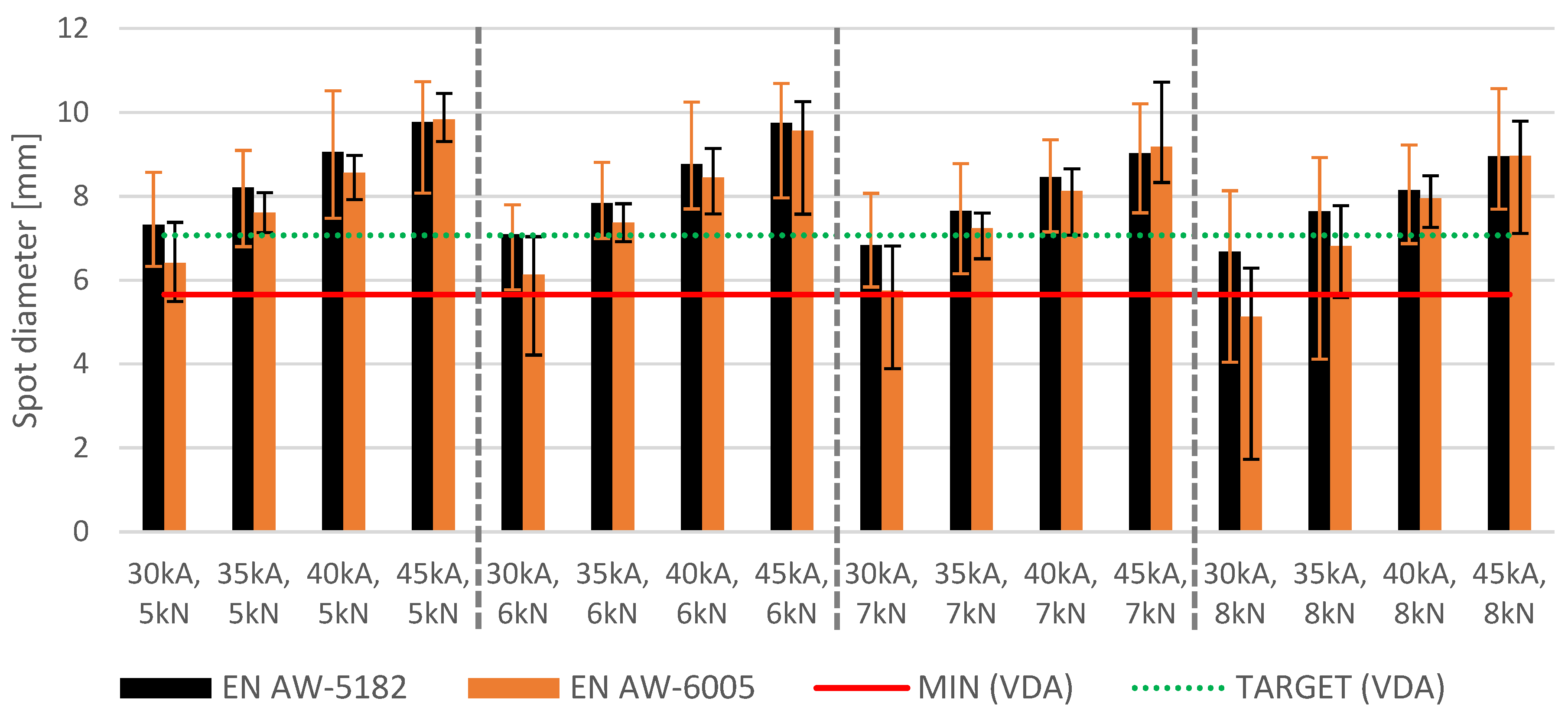

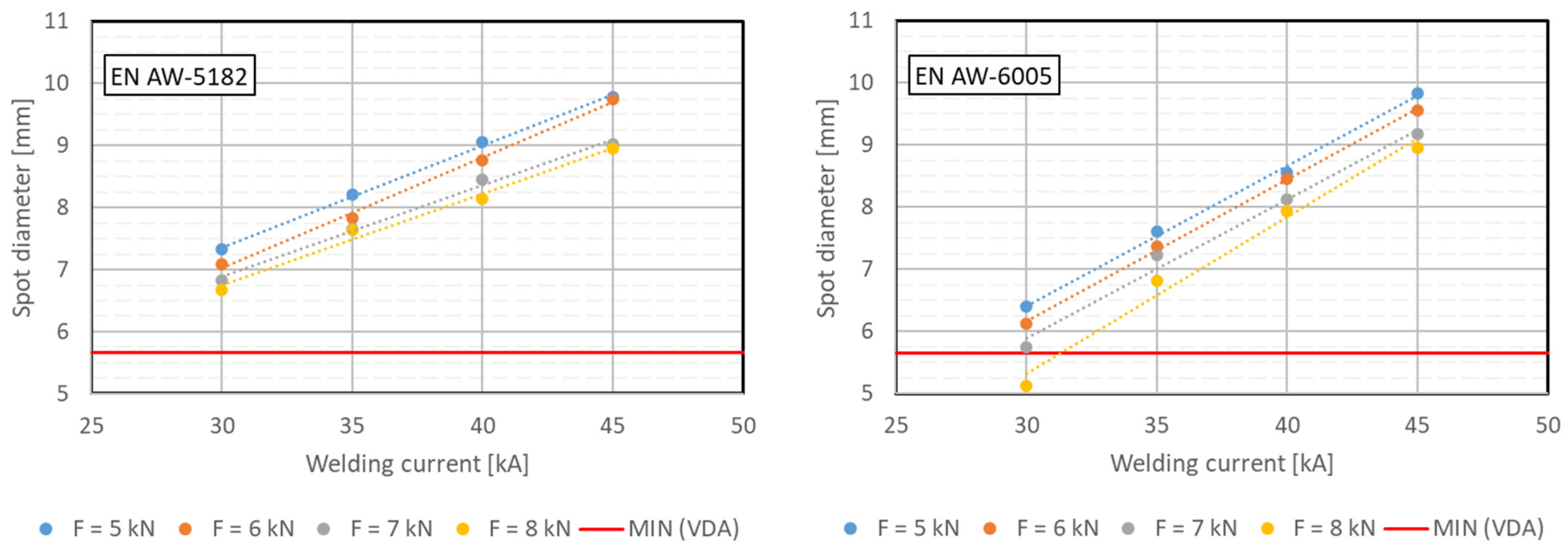

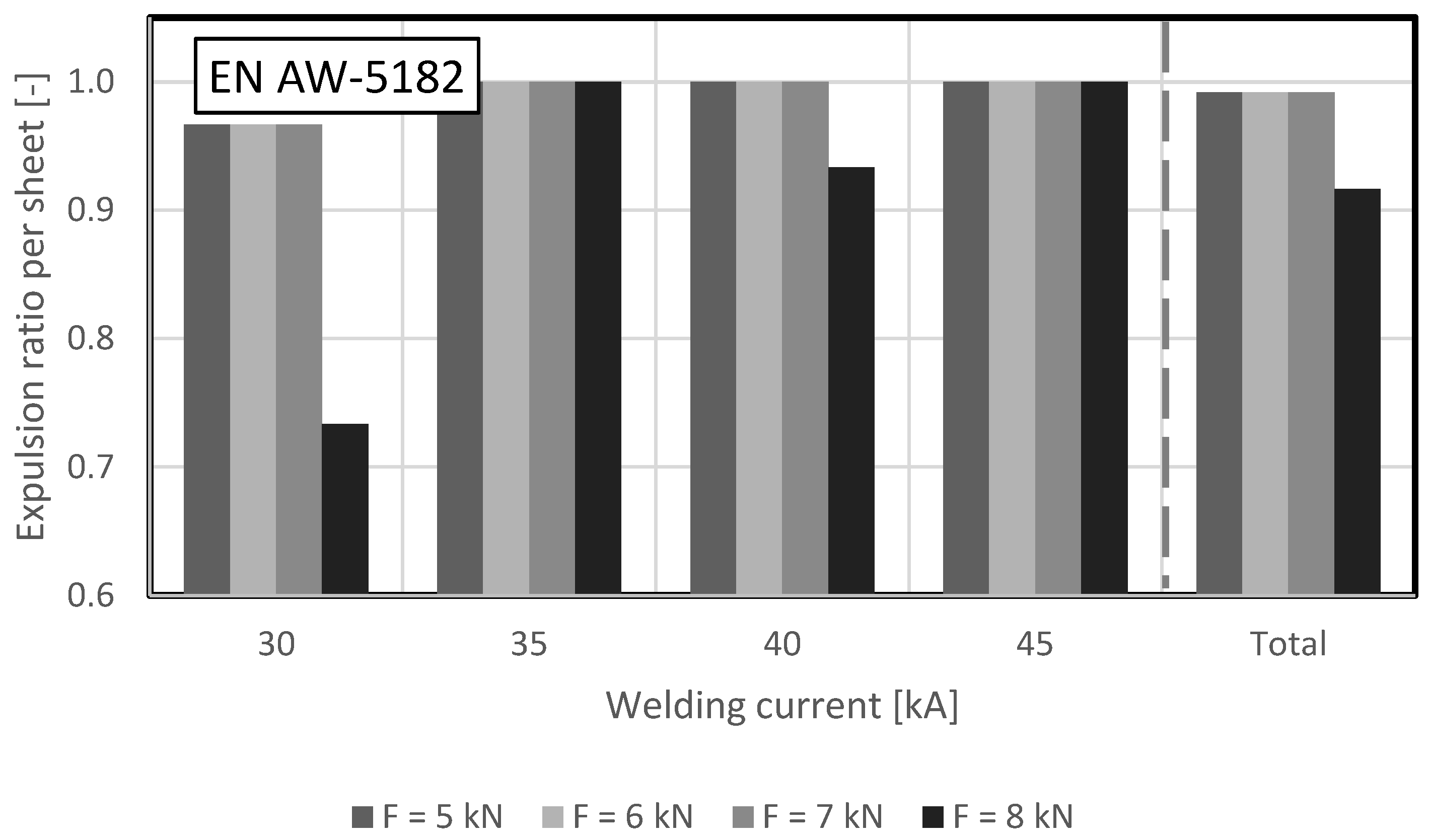

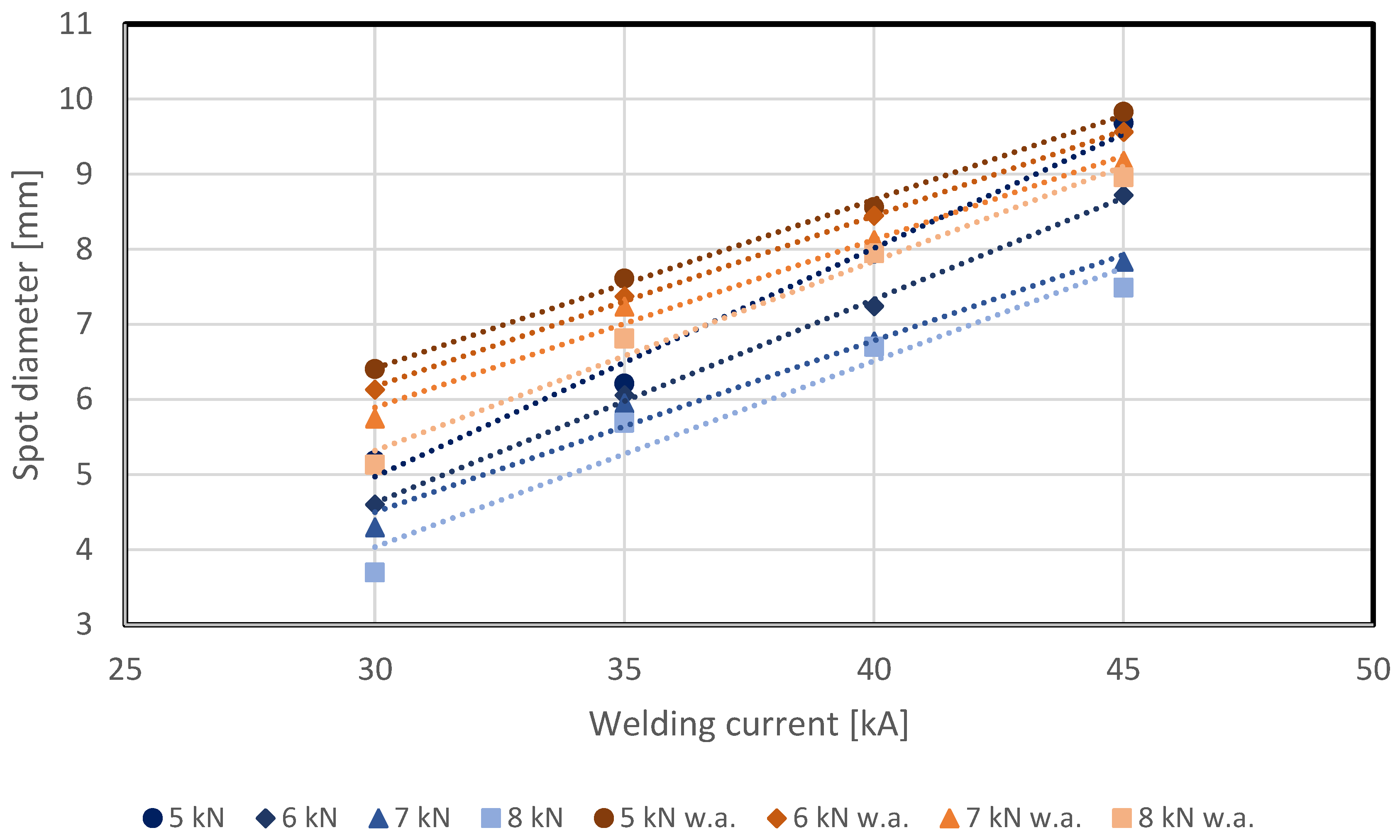

3.1. Influence of Welding Current and Electrode Force on Spot Diameter and Expulsion

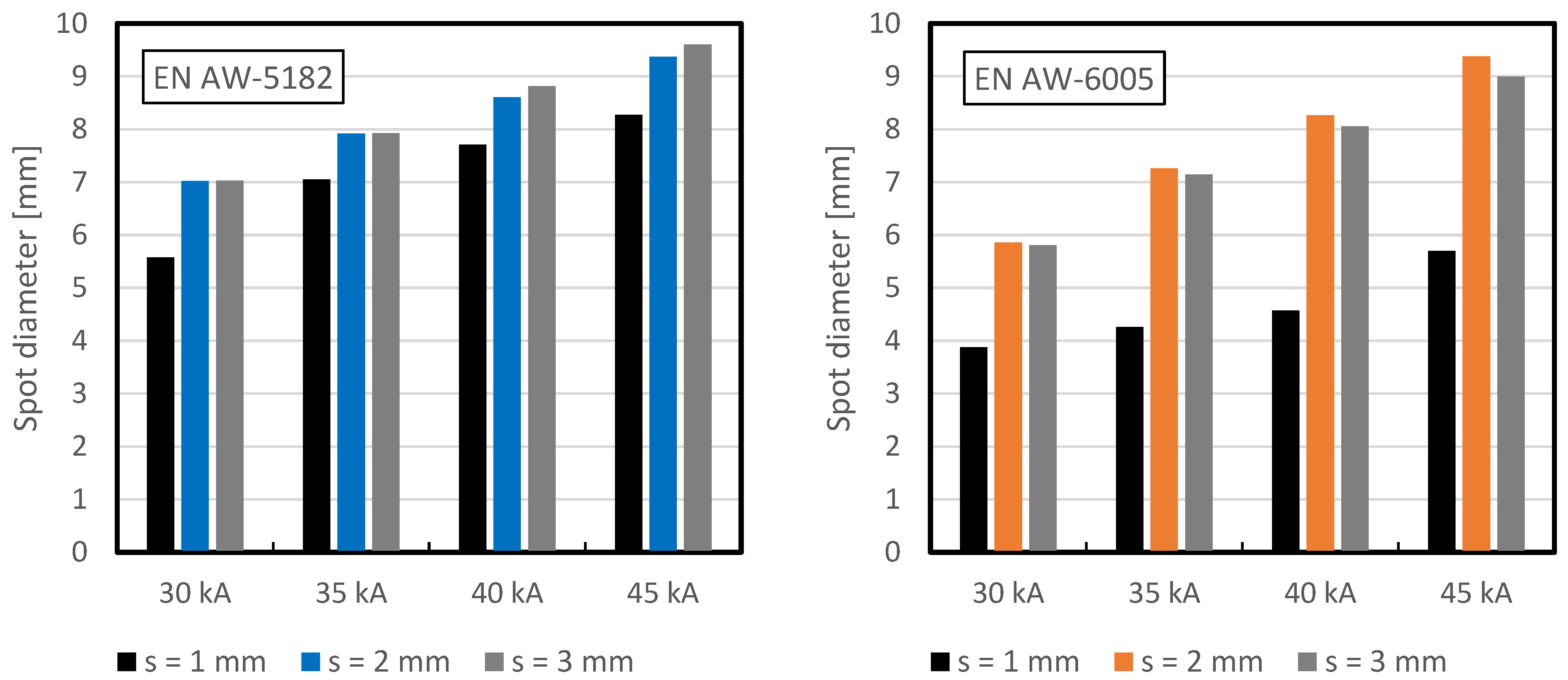

3.2. Influence of Sheet Thickness on Spot Diameter

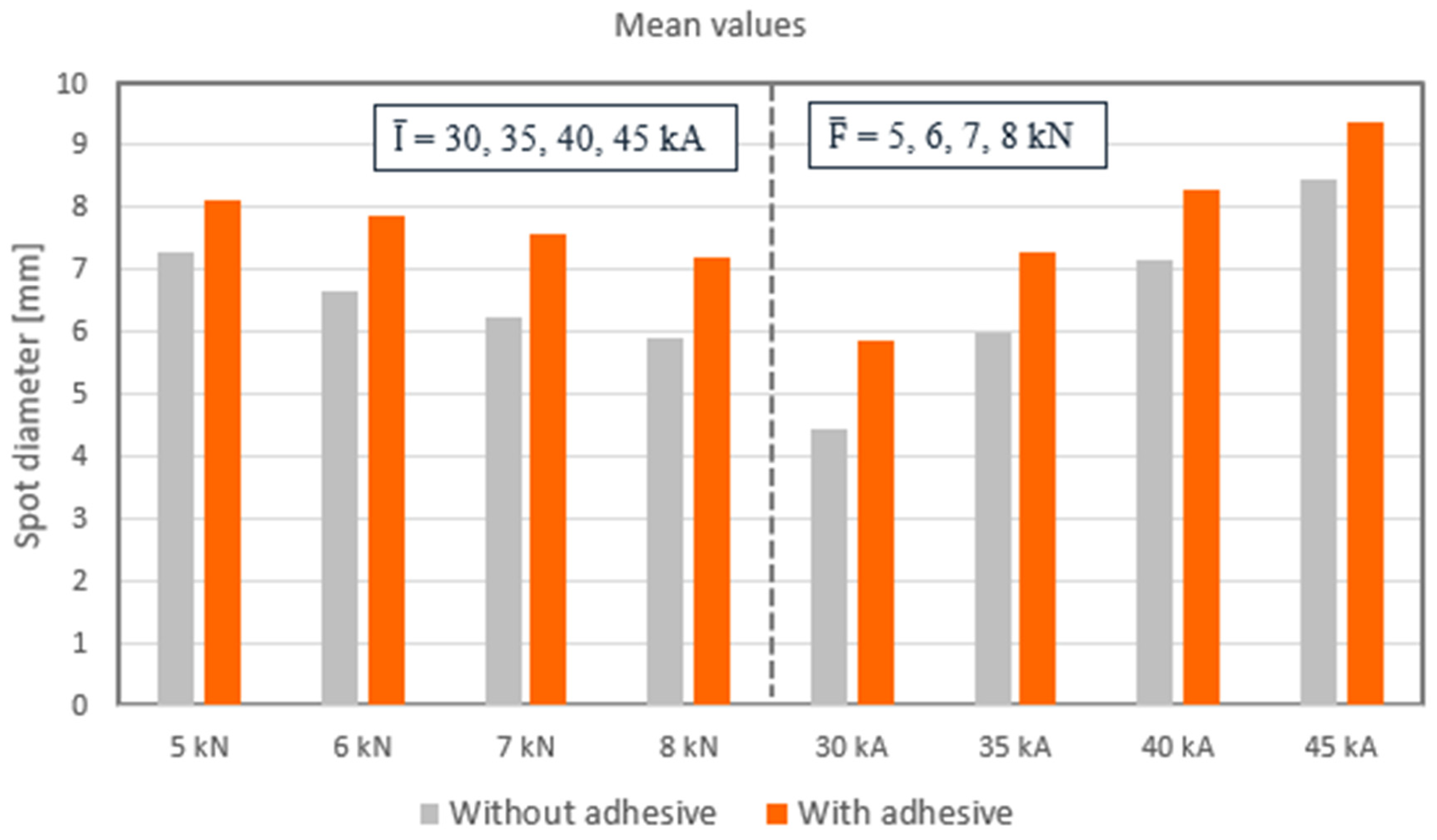

3.3. Influence of Adhesive BETAMATE™ 1640 on Spot Diameter

4. Conclusions

- Spot diameter increases with increasing welding current and decreases with increasing electrode force. The range significantly below the minimum spot diameter specified in the VDA recommendation 238-401 [36] was not considered in this study.

- EN AW-5182 has a very high probability of expulsion, while EN AW-6005 had no expulsions. The same welding profile was used for both alloys, suggesting that adjusting the welding profile for EN AW-5182 would be beneficial. In addition to adjusting the welding current, adjusting the electrode force profile would also be advantageous.

- A change in current affects EN AW-6005 more than EN AW-5182. It should be noted that EN AW-5182 had a spatter rate of 97%, while EN AW-6005 exhibited no spatter, which also affects the spot diameter.

- Welding with adhesive BETAMATE™ 1640 results in larger spot diameters. This was observed with both alloys.

- With a sheet thickness of 1 mm, smaller spot diameters were achieved than with 2 mm, regardless of the alloy. With a sheet thickness of 3 mm, the spot diameters were similar to those achieved with 2 mm thick sheets, and in some cases, even slightly smaller.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nadimi, N.; Yadegari, R.; Pouranvari, M. Resistance Spot Welding of Quenching and Partitioning (Q&P) Third-Generation Advanced High-Strength Steel: Process–Microstructure–Performance. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2023, 54, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.-L.; Rao, Y.-Z.; Zhang, Q.-X.; Xia, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.; Wu, F.; Li, Y.-B.; Yan, D.-J. Effect of storage time on the surface status and resistance spot weldability of TiZr pretreated 5182 aluminum alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 81, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, R.; Wärmefjord, K.; Lindkvist, L.; Berlin, R. The influence of spot weld position variation on geometrical quality. CIRP Ann. 2012, 61, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, F.; Luo, Z.; Chao, Y.J.; Ao, S.; Cui, X. Weld Growth Mechanisms and Failure Behavior of Three-Sheet Resistance Spot Welds Made of 5052 Aluminum Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2015, 24, 2546–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Li, F.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y. Improve resistance spot weld quality of advanced high strength steels using bilateral external magnetic field. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 52, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilthey, U. Schweißtechnische Fertigungsverfahren 1 [Welding Manufacturing Processes 1]: Schweiß- und Schneidtechnologien [Welding and Cutting Technologies], 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, H.E. Leichtbau in der Fahrzeugtechnik [Lightweight Construction in Automotive Engineering], 2nd ed.; Springer Vieweg: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, J. Aluminium in Innovative Light-Weight Car Design. Jap. Inst. Met. Mat.—Mat. Trans. 2011, 52, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisza, M.; Czinege, I. Comparative study of the application of steels and aluminium in lightweight production of automotive parts. Int. J. Light. Mat. 2018, 1, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermann, F. Anwendungstechnologie Aluminium [Application Technology Aluminum], 3rd ed.; Springer Vieweg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, J.E. Joining Aluminum Sheet in the Automotive Industry—A 30 Year History. Weld. Res. 2012, 91, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Emadi, P.; Andilab, B.; Ravindran, C. Engineering Lightweight Aluminum and Magnesium Alloys for a Sustainable Future. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2022, 102, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Krause, A.R.; Davies, R.G. Contact Resistances in Spot Welding. Weld. Res. Suppl. 1996, 75, 402–412. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, K.J. Beitrag zur Qualitätssicherung Durch Analyse des Widerstandspunktschweißprozesses beim Fügen von Aluminiumwerkstoffen [Contribution to Quality Assurance by Analyzing the Resistance Spot Welding Process When Joining Aluminum Materials]. Ph.D. Dissertation, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Biele, L.; Schaaf, P.; Schmid, F. Method for contact resistance determination of copper during fast temperature changes. J. Mat. Sci. Mat. Electron. 2021, 56, 3827–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanlar, S.; Ogur, A.; Ozsarac, U.; Ilhan, E. Welding time effect on mechanical properties of automotive sheets in electrical resistance spot welding. Mat. Des. 2008, 29, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Orozco, J.; Indacochea, J.E.; Chen, C.H. Resistance Spot Welding: A Heat Transfer Study: Real and simulated welds were used to develop a model for predicting temperature distribution. Weld. J. 1989, 68, 363–371. [Google Scholar]

- DVS 2929-1; Messung des Übergangswiderstands—Grundlagen, Messmethoden und -Einrichtungen [Method for Determining the Transition Resistance—Basics, Measurement Methods and Set-Up]. DVS—Deutscher Verband für Schweißen und Verwandte Verfahren e.V.; DVS Media GmbH: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2014.

- Leuschen, B. Beitrag zum Tragverhalten von Aluminum- und Aluminium/Stahl-Widerstandspunktschweissverbindungen bei Verschiedenartiger Beanspruchung [Contribution to the Load-Bearing Behavior of Aluminum and Aluminum/Steel Resistance Spot Welded Joints Under Different Types of Stress]. Ph.D. Dissertation, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, D.R.; Bhattacharya, S. Dynamic Resistance and Its Application to In-Process Control of Spot Welding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Exploiting Welding in Production Technology, London, UK, 22–24 April 1975; pp. 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, P.; Xuan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Su, H. Review on Techniques for On-Line Monitoring of Resistance Spot Welding Process. Adv. Mat. Sc. Eng. 2013, 2013, 630984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D.W.; Franklin, J.E.; Stanya, A. Characterization of Spot Welding Behavior by Dynamic Electrical Parameter Monitoring. Weld. Res. Suppl. 1980, 59, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gedeon, S.A.; Eagar, T.W. Resistance Spot Welding of Galvanized Steel: Part II. Mechanisms of Spot Weld Nugget Formation. Met. Trans. B 1986, 17B, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, W.F.; Nippes, E.F.; Wassell, F.A. Dynamic contact resistance of series spot welds. Weld. J. 1978, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, E.P.; Auhl, J.R.; Sun, T.S. Understanding the Process Mechanisms Is Key to Reliable Resistance Spot Welding Aluminum Auto Body Components; SAE Technical Paper Series; 400 Commonwealth Drive; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Piott, M.; Werber, A.; Schleuss, L.; Doynov, N.; Ossenbrink, R.; Michailov, V.G. Numerical and experimental analysis of heat transfer in resistance spot welding process of aluminum alloy AA5182. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 1671–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezer, A.; Weihe, S.; Werz, M. Method for Determining the Contact and Bulk Resistance of Aluminum Alloys in the Initial State for Resistance Spot Welding. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Thornton, M.; Boomer, D.; Shergold, M. A correlation study of mechanical strength of resistance spot welding of AA5754 aluminium alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2011, 211, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Thornton, M.; Boomer, D.; Shergold, M. Effect of aluminium sheet surface conditions on feasibility and quality of resistance spot welding. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2010, 210, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezer, A.; Weihe, S.; Werz, M. Influences of Various Parameters on the Weld Spot Diameter during Resistance Spot Welding of the Aluminum Alloy EN AW-6005. Struct. Integr. Proc. 2026; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, E.; Wagner, H.; Schubert, H.; Zhang, W.; Balasubramanian, B.; Brewer, L.N. Short-Pulse Resistance Spot Welding of Aluminum Alloy 6016–T4—Part. Weld. J. 2021, 100, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, L.; Deng, L.; Li, Y. Effect of external magnetic field on resistance spot welding of aluminum alloy AA6061-T6. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 50, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, R.S.; Bammann, D.J.; Yeldell, A.; Solanki, K.N.; Hammi, Y. Welding parameters influence on fatigue life and microstructure in resistance spot welding of 6061-T6 aluminum alloy. Mater. Des. (1980–2015) 2013, 45, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.M.; Ferreira, J.M.; Loureiro, A.; Costa, J.; Bártolo, P.J. Effect of process parameters on the strength of resistance spot welds in 6082-T6 aluminium alloy. Mater. Des. (1980–2015) 2010, 31, 2454–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, P.; Gintrowski, G.; Liang, Z.; Schiebahn, A.; Reisgen, U.; Precoma, N.; Geffers, C. Development of a new approach to resistance spot weld AW-7075 aluminum alloys for structural applications: An experimental study—Part 1. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 5569–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDA 238-401; Vorgabe zur Prüfung der Schweißeignung von Aluminiumblechwerkstoffen Durch Widerstandspunktschweißen (WPS) [Requirements for Testing the Weldability of Aluminium Sheet Alloys Using Resistance Spot Welding (RSW)]. Verband der Automobilindustrie e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- VDA 239-200; Flacherzeugnisse aus Aluminium [Aluminium Sheet Material]. Verband der Automobilindustrie e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- DIN EN 573-3; Aluminium und Aluminiumlegierungen—Chemische Zusammensetzung und Form von Halbzeug—Teil 3: Chemische Zusammensetzung und Erzeugnisformen [Aluminium and Aluminium Alloys—Chemical Composition and Form of Wrought Products—Part 3: Chemical Composition and Form of Products]. DIN—Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2024.

- DVS 2916-1; Prüfen von Widerstandspressschweißverbindungen—Zerstörende Prüfung, Quasistatisch [Testing of Resistance Welded Joints—Destructive Testing, Quasi Static]. DVS—Deutscher Verband für Schweißen und Verwandte Verfahren e.V.; DVS Media GmbH: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2014.

- DIN EN ISO 10447; Widerstandsschweißen—Prüfung von Schweißverbindungen—Schäl- und Meißelprüfung von Widerstandspunkt- und Buckelschweißverbindungen [Resistance Welding—Testing of Welds—Peel and Chisel Testing of Resistance Spot and Projection Welds]. DIN—Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2015.

- Leuschen, B. Fügen von Aluminium-Karosseriewerkstoffen [Joining Aluminum Body Materials], Aluminium-Werkstofftechnik für den Automobilbau [Aluminum Materials Technology for Automotive Construction]; Ostermann, F., Ed.; Expert-Verlag: Ehningen, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Haselhuhn, A.S.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Carlson, B.E.; Lin, Z. Comparison of the Resistance Spot Weldability of AA5754 and AA6022 Aluminum to Steels. Weld. J. 2020, 2020, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Ao, S.; Chao, Y.J.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y. Application of Pre-heating to Improve the Consistency and Quality in AA5052 Resistance Spot Welding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2015, 24, 3881–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.K. Materials, Design, and Manufacturing for Lightweight Vehicles; Woodhead Publishing: Duxford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA; Kidlington, UK; Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| EN AW-5182 (AlMg4.5Mn0.4) (AL5-STD) | Si | Fe | Cu | Mn | Mg | Cr | Zn | Ti | V |

| Chemical Composition [37,38] | ≤0.20 | ≤0.35 | ≤0.15 | 0.20–0.50 | 4.00–5.00 | ≤0.10 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.10 | - |

| s = 1 mm | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 4.31 | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| s = 2 mm | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 4.80 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.010 |

| s = 3 mm | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 4.35 | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.010 |

| * EN AW-6005 * (AlMg0.6Si0.6V) ** (AL6-HDI) | Si | Fe | Cu | Mn | Mg | Cr | Zn | Ti | V |

| * Chemical Composition [38] | 0.60–0.90 | ≤0.35 | ≤0.10 | ≤0.10 | 0.40–0.60 | ≤0.10 | ≤0.10 | ≤0.10 | - |

| ** Chemical Composition [37] | ≤1.50 | ≤0.35 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.30 | ≤0.90 | ≤0.15 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.15 | ≤0.10 |

| s = 1 mm | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.024 | 0.01 |

| s = 2 mm | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.024 | 0.01 |

| s = 3 mm | 0.73 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.60 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.024 | 0.01 |

| Parameter | Subsection | Parameter Variations | Boundaries | Number of Sheet Pairs | Number of Weld Spots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welding current | Section 3.1 | 30/35/40/45 kA | Sheet thickness: 2 mm Adhesive: yes | 16 | 480 |

| Electrode force | Section 3.1 | 5/6/7/8 kN | Sheet thickness: 2 mm Adhesive: yes | 16 | 480 |

| Sheet thickness | Section 3.2 | 1/2/3 mm | Adhesive: yes | 3 × 16 = 48 | 3 × 480 = 1440 |

| Adhesive | Section 3.3 | With/Without adhesive BETAMATE™ 1640 | Sheet thickness: 2 mm | 2 × 16 = 32 | 2 × 480 = 960 |

| F [kN] | m (EN AW-5182) [-] | m (EN AW-6005) [-] |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.164 | 0.225 |

| 6 | 0.178 | 0.227 |

| 7 | 0.148 | 0.224 |

| 8 | 0.147 | (0.252) |

| Mean Value | 0.159 | 0.225 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fezer, A.; Weihe, S.; Werz, M. Effects of Process Parameters, Sheet Thickness and Adhesive on Spot Diameter During Resistance Spot Welding of Aluminum Alloys EN AW-5182 and EN AW-6005. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2026, 10, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10020050

Fezer A, Weihe S, Werz M. Effects of Process Parameters, Sheet Thickness and Adhesive on Spot Diameter During Resistance Spot Welding of Aluminum Alloys EN AW-5182 and EN AW-6005. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2026; 10(2):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10020050

Chicago/Turabian StyleFezer, Andreas, Stefan Weihe, and Martin Werz. 2026. "Effects of Process Parameters, Sheet Thickness and Adhesive on Spot Diameter During Resistance Spot Welding of Aluminum Alloys EN AW-5182 and EN AW-6005" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 10, no. 2: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10020050

APA StyleFezer, A., Weihe, S., & Werz, M. (2026). Effects of Process Parameters, Sheet Thickness and Adhesive on Spot Diameter During Resistance Spot Welding of Aluminum Alloys EN AW-5182 and EN AW-6005. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 10(2), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp10020050