1. Introduction

For the first time in 2003, the concept of digital counterparts was formulated by Michael Greaves [

1], who introduced this definition as part of a product lifecycle management course at the University of Michigan in the USA. Despite the fact that this technology did not receive a wide response at the beginning, it later became very popular.

The most significant industry in the application of digital counterparts’ technology today is machine building; more than 47% of publications in the Scopus database are devoted to topics related to digital counterparts manufacturing systems [

2]. Here, first of all, we focus on building digital counterparts of various technological processes and objects of production systems, including metalworking machines.

In general, the use of digital counterparts in metalworking control systems makes it possible to solve the problems of increasing the efficiency and reliability of machine tools. In a more differentiated way, these tasks can be divided into the following subcategories:

- -

Forecasting and controlling of the accuracy and quality of their metal parts;

- -

Reducing the number of errors in the cutting process. The use of digital counterparts allows minimizing the human factor in the process of setting up and monitoring the operation of machines;

- -

Forecasting and diagnosing the wear resistance of cutting tools: Digital counterparts allow us to monitor the condition of the tool during operation, assessing its wear and performance. This allows us to take measures in advance to replace the tool before it leads to a deterioration in the quality of processing or machine failure;

- -

Predicting the occurrence of malfunctions and making decisions about preventive maintenance. The digital counterpart can predict the development and occurrence of malfunctions in both the machine and the tool, which will reduce the risks of equipment failures and save the organization’s resources;

- -

Optimization of technological and production processes. Digital counterparts based on mathematical modeling can design and test both tools and processing conditions, which avoids the need to create physical prototypes and conduct multiple tests. Here, on the basis of virtual models of the digital twin, it is possible to select optimal tools for cutting new alloys, as well as calculate optimal processing modes;

- -

Real-time diagnostics. Digital counterparts continuously exchange information with a physical object, updating data, and providing access to monitoring, diagnostic, and analysis functions through web services and applications. This simplifies the work with big data and allows staff to respond promptly to changes in the state of the equipment.

Summarizing all the factors mentioned above, two main areas can be distinguished in which the use of digital counterpart technology has the greatest prospects: forecasting and quality control of the parts obtained during cutting, as well as forecasting and monitoring the wear resistance of cutting tools. These areas are most clearly represented in cases where flexible equipment conversion is required to perform new tasks. At the same time, the selection of processing modes, cutting tools, etc., is important to consider. This can be performed on the basis of modeling virtual models of a digital counterpart, where both the quality and accuracy of the parts being manufactured and the life of the tool will be evaluated in terms of the required durability from the point of view of these operations.

Various methods based on physical and statistical models, as well as combinations of them, are used to create digital counterparts of metal-cutting machines. At the same time, physical models imply the construction of systems of integrodifferential equations describing the complex evolutionary dynamics of cutting processes [

3,

4,

5], and statistical models can be based on data processing using machine learning algorithms (regression analysis methods, neural network algorithms, etc.) [

6,

7,

8]. It is also possible to combine these two approaches, when, for example, neural network models participate in the preparation of data for calculations in conventional mathematical models of a digital counterpart [

9].

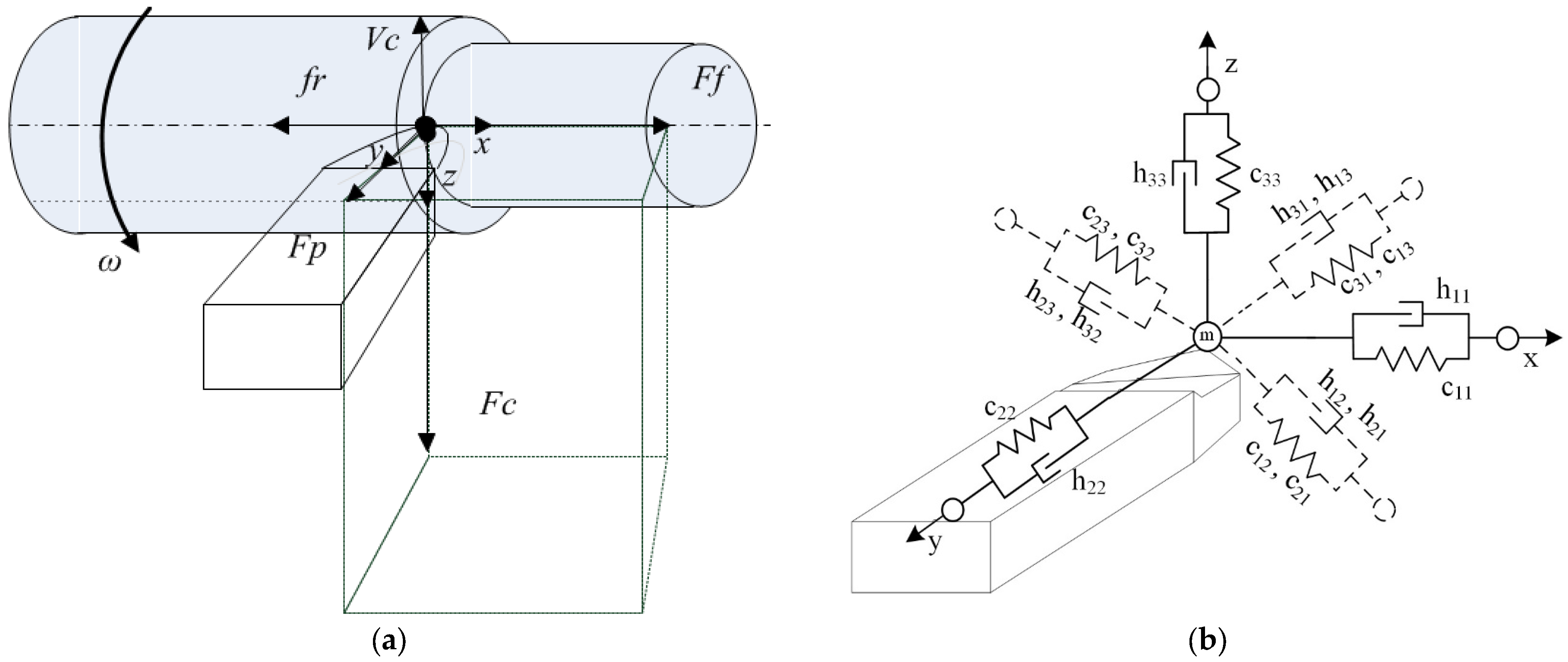

For a long time, the synthesis of mathematical models of cutting processes was based on a purely mechanistic approach based on the hypothesis of the proportionality of the cutting force to the area of the cut layer [

10,

11], which subsequently allowed us to assume the importance of the influence of variation in this area on the regeneration of vibrations in the cutting system [

12]. However, a large number of modern researchers believe that the vibration dynamics of the cutting process also largely depends on temperature effects during metal-cutting [

13,

14,

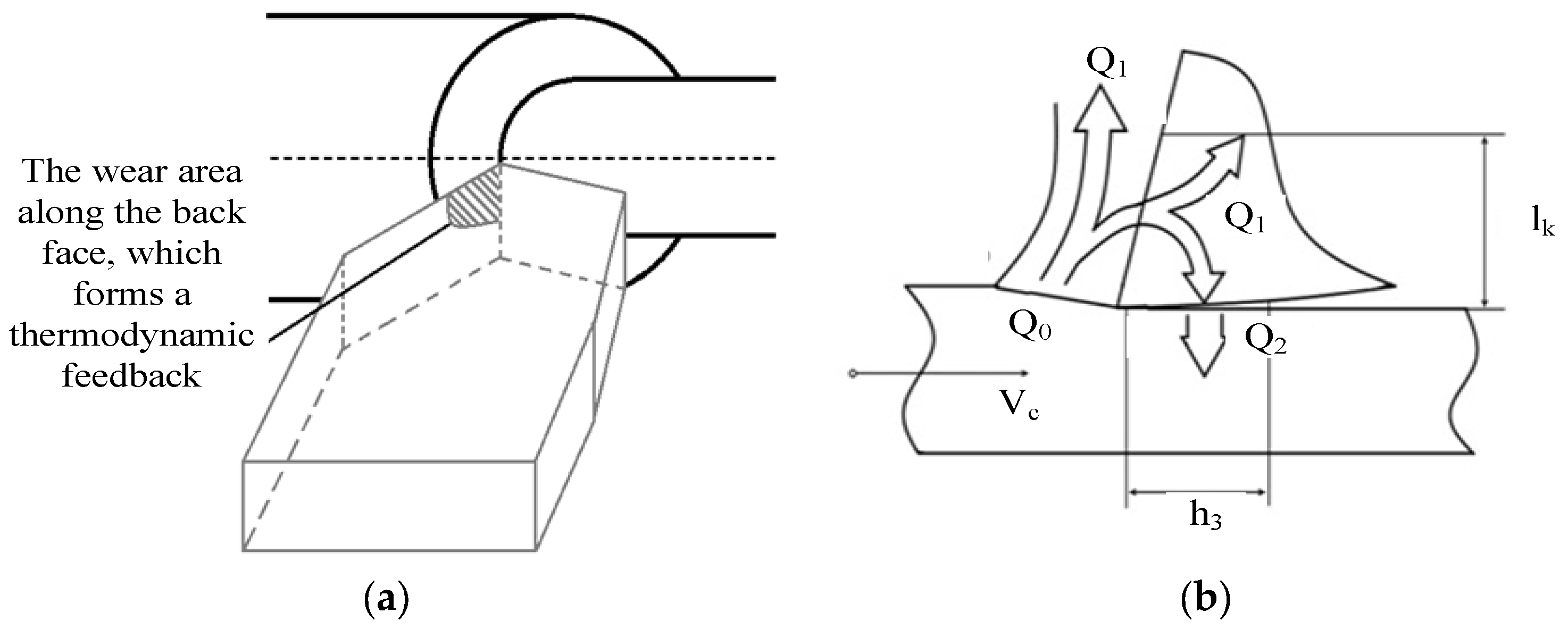

15]. Thus, the cutting temperature is the most important factor in metalworking on metal-cutting machines, including turning machines, but the term cutting temperature itself shows the imperfection of the approach to the construction of any models based on this term. The main problem is that there will be different temperatures in different parts of the contact between the tool and the workpiece. This is most clearly illustrated by the generally accepted scheme of heat flows, widely presented in [

16,

17], which represents a general approach to the formation of temperature in this zone based on the accepted view in metalworking. According to this view of the processes of cutting and friction, the contact zone of the tool and the workpiece can be divided into three zones from the point of view of sources of additional temperature release: the zone of primary deformation, the friction zone along the back face, and the friction zone on the front face of the tool [

18]. Here, in these zones, in addition to the processes of converting power into temperature, the released thermal energy is dissipated through the resulting heat flows. The heat flows are directed deep into the workpiece and cause its subsequent heating, into the chips, which dissipate the main heat from the cutting area, as well as into the cutting tool, which is heated through the front and back edges.

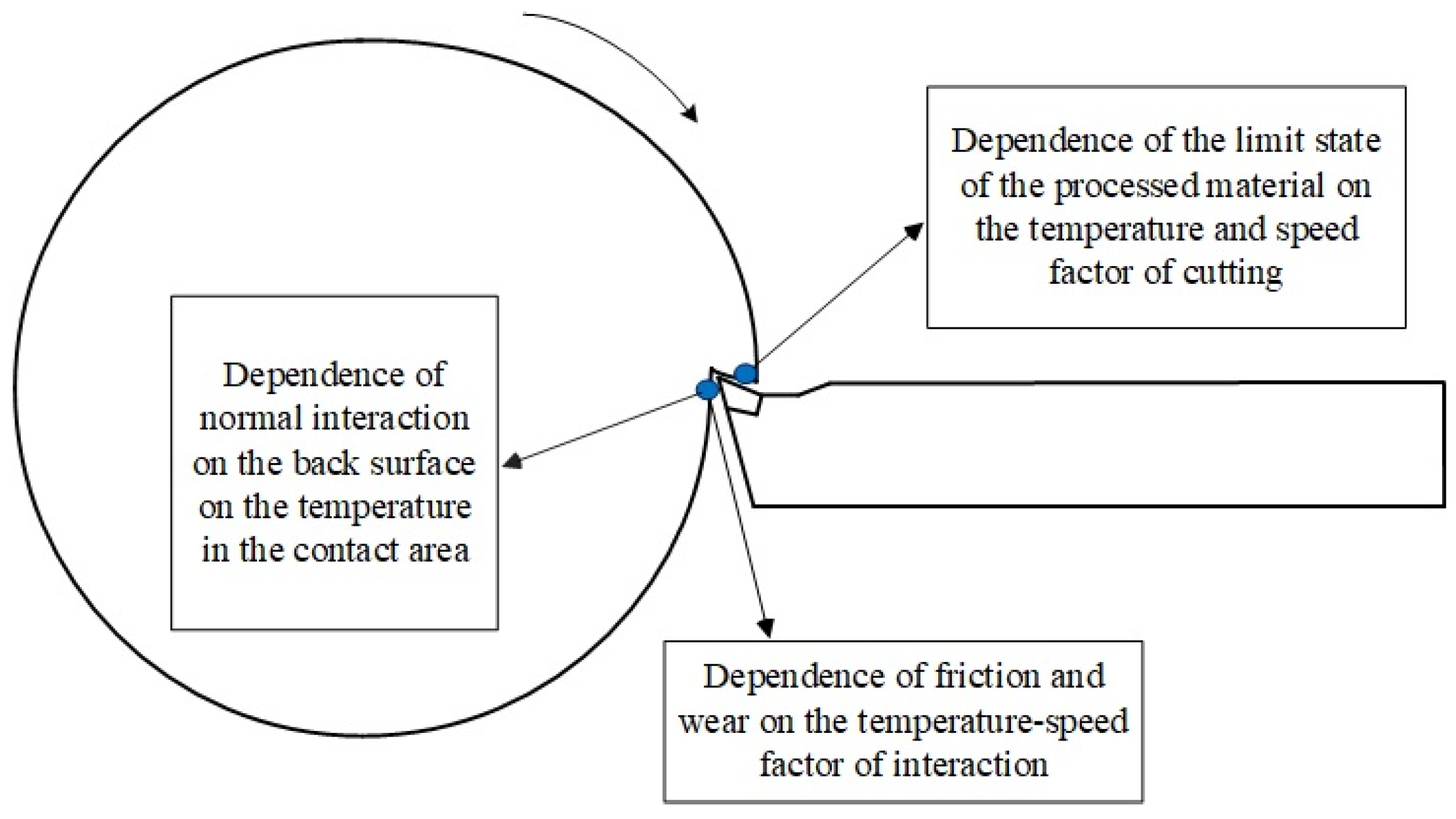

One of the promising modern approaches to building control systems is the synergetic control method, where the cutting process control system interacts with its digital counterpart. For this option, when building models of a digital counterpart based on the disclosure of the physical foundations of the processes occurring during metalworking in metal-cutting machines, it is important to observe a synergetic concept in the formation of these models. Firstly, a synergetic approach to the analysis and synthesis of controlled machining processes on metal-cutting machines implies a related system representation of metalworking processes by cutting [

19]. The related and systemic representation here refers to the interconnectedness of subsystems of the cutting control system. In addition, the synergetic concept includes a provision on the expansion of the dimension of the state space of the control system and its subsequent compression. It is the introduction of thermodynamics of processes into mathematical models based on differential equations that can become the basis for such an expansion and subsequent compression of the dimension of the state space [

20].

Expansion can be understood as the consideration of a separate subsystem of equations describing the thermodynamics of processes, and compression can be implemented by introducing thermodynamics into the description of the force reaction in the coordinates of the thermodynamic subsystem. It should be noted here that, until today, the elastic–thermodynamic interaction has not been considered; however, temperature has been taken into account as a separate factor affecting the cutting process in one way or another. As it is noted, the synergetic concept determines the properties of the control system through an interaction; the development of a new theory of elastic–thermodynamic interaction will allow us to take a fresh look at the already-known properties and characteristics of the cutting process.

In addition to improving the accuracy of modeling the processes occurring during metal-cutting, an important task is to find optimal cutting modes based on the analysis of the obtained models. It should be noted that a large number of papers describing the experimental dynamics of the cutting process indicate the existence of such an optimal cutting mode. Thus, in [

21], it is indicated that for the case of dry turning tool steel 60CrMoV18-5 on a CNC machine and using a cutting plate made of cubic boron nitride, a model of the cutting system was created using dispersion analysis (ANOVA). Subsequently, based on the full quadratic regression model, an algorithm was developed that can be used to obtain optimal values of cutting conditions. The article by Kumar P. and Chauhan S. R. discusses the finishing turning of hardened die-cast tool steel. In this study, the influence of processing parameters, including the hardness of the workpiece in the range of 45–55 HRC, on the cutting force (F c and F t), surface roughness (R a), and cutting edge temperature (T) during the finishing turning of the AISIH13 die tool steel with cubic boron nitride plates was studied [

22]. Here, the authors point out that the cutting force is primarily influenced by the hardness of the workpiece material, as well as the feed and cutting depth. The conducted studies have shown that the selection of optimal cutting parameters will improve the quality of the surfaces obtained during fine turning. However, all these works, and many others, have a strictly practical focus and do not lead to the emergence of new scientific theories explaining the patterns identified by the authors of these works. Henri Poincare also argued that science begins where a new axiomatics is formed, or in other words, where a new theory is formed. It is the new theory that will make it possible to justify the optimization of metalworking processes by cutting at a new, higher level.

In this regard, the aim of this study is to form a new theory of the elastic–thermodynamic interaction during cutting, which will improve the adequacy of the mathematical modeling of the interrelated thermodynamics of cutting processes on metal-cutting machines. To achieve this goal, we identified three consecutive tasks:

- -

Synthesis of a finite-dimensional model of elastic–thermodynamic interaction during cutting, which, as output coordinates, will have the values of the vibration acceleration of the tip of the cutting tool and cutting force decomposed along the coordinates of deformation of the tip of the cutting tool, as well as temperature in the cutting zone;

- -

Conducting a series of experiments using a modern measuring complex that allows measuring vibration acceleration, forces, and temperature;

- -

Validation of the previously obtained model based on the results of comparing experimentally determined values of forces and temperatures and their values obtained when modeling a new mathematical model.

3. Validation of the Mathematical Model

3.1. Description of the Experiments

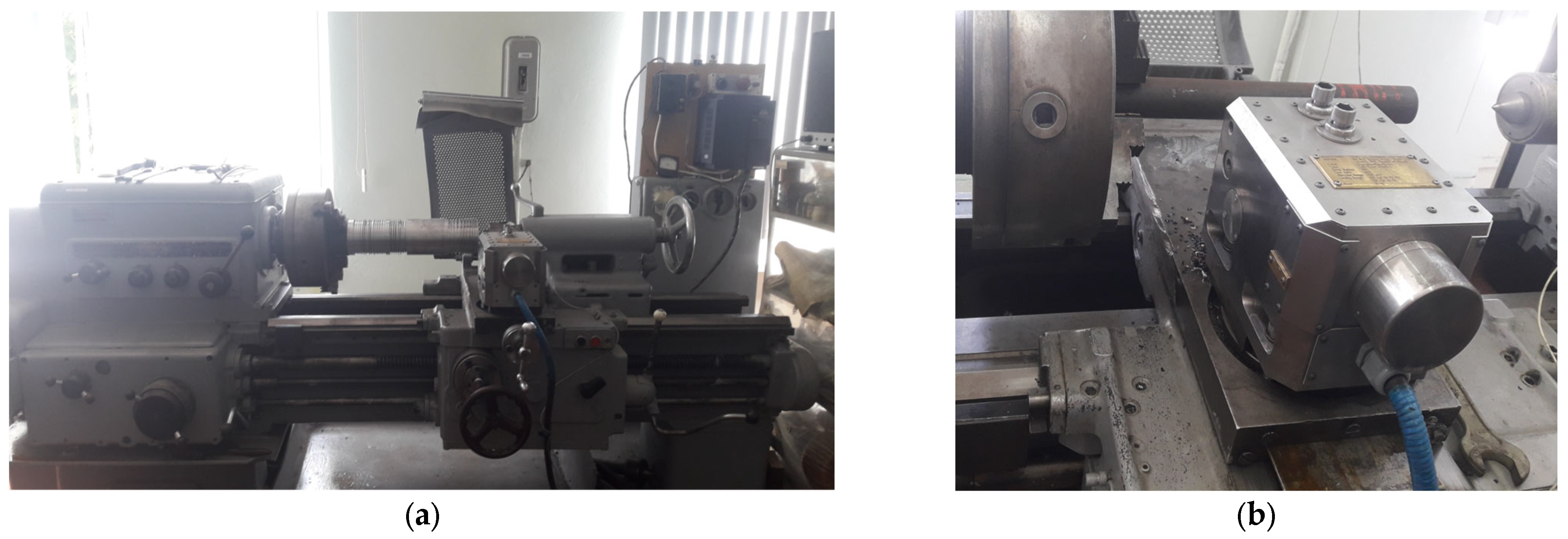

In all cases, a 1K625 lathe was used to conduct the experiment (see

Figure 4), which has a stand for studying cutting modes during turning STD.201-1, also shown in

Figure 2.

The machine shown in

Figure 4 was previously upgraded, the control of the motor providing the operating modes on the machine was switched to frequency control, and the frequency controller is shown in the upper right corner of

Figure 4. Thanks to this, it became possible to smoothly adjust the cutting speed within the selected operating mode of the machine.

To measure the force response from the cutting process to the shaping movements of the tool, tool vibrations, and the power of irreversible transformations (temperature), STD.201-1 was installed on the machine instead of the standard caliper. The stand shown in

Figure 4 was designed to study the dynamic and thermal processes occurring during metal-cutting in various modes as part of lathes. STD.201-1 functionally consists of a tool holder head, an interface unit, a personal computer, and a set of cables. The tool holder head was mounted on the machine support and includes a set of sensors that convert the dynamic and vibrational effects on the cutting tool into electrical signals sent to the interface unit via a set of cables. The interface unit had a block structure and consisted of electronic components manufactured by National Instruments. The electronic components were installed in the NI cDAQ-9174 chassis, which was connected to a PC via USB2.0.

To validate the mathematical model of the thermodynamics of the cutting system, the experiment was conducted on the described equipment. The main purpose of the experiment was to study the effect of the dynamics of the cutting process on the formation of a temperature field in the contact area of the tool and the workpiece. By changing the dynamics of the cutting process, we mean the mutual influence of tool wear on the cutting process and the cutting process on tool wear, such a mutual influence was carried out through a force reaction formed in the cutting area. Measuring this reaction, as well as measuring the thermal EMF formed in the contact zone of the tool and the workpiece, allowed us to evaluate the influence of the dynamics of the cutting process on the formation of a temperature field in the contact zone of the tool and the workpiece.

For this experiment, we continuously turned a shaft-type part with the same processing parameters, while controlling the degree of wear of the tool and the change in the force reaction from the cutting process as a result of the effect of the wear of the rear face on the dynamics of the process.

The data on changes in forces, vibrations, and temperature in the cutting area, presented in this form, are difficult to process. For a more convenient presentation of information, the program provides the ability to display the entire array of measurements in MS Excel. Unfortunately, it is not possible to present all the displays in full, since only the first step of the experiment is displayed as a 15,916-page MS Excel document. To fully describe the experiment, it would be necessary to attach seven such documents as an appendix to the work. It follows from this that the STD.201-1 interface outputs different amounts of different data for the same time period. For example, for the time corresponding to 0.01 s of this experiment, this represents seven different values of force along the x coordinate, and for the time corresponding to 0.02 s, there are already eight such values. As a result of processing the data from the arrays obtained in the experiment, refined force values were determined, for example, the force response to the shaping movements of the instrument along the y coordinate, after processing in MATLAB.

The technological parameters of the experiment have the following values: processed material grade 45 steel, pentahedral cutting plate 10113-110408 T15K6 (Kuznetskie Mashiny, Kuznetsk, Russia), cutting speed Vr = 124 m/min, cutting feeds S = 0.11 mm/rev, and cutting depth tp = 1 mm. The numerical calculation of the mathematical model represented by the system of Equation (13) was carried out in the MATLAB 2018 b environment; the step of integration (quantization) of the signal was 0.001 s, or, in other words, 1000 measurements per second.

Due to the specified features of the interface of the measuring complex STD.201-1, the main limitation was the amount of information undergoing subsequent processing. The limited memory buffer of the analog-to-digital converter of the complex did not allow us to make a sufficiently high-quality digital interpretation for all three types of measured data (forces, vibrations, temperature).

3.2. Results

In total, seven measurements of forces, temperature, and vibration activity were performed. This article presents only a part of the results of comparing experimental data and data obtained during modeling in the MATLAB environment.

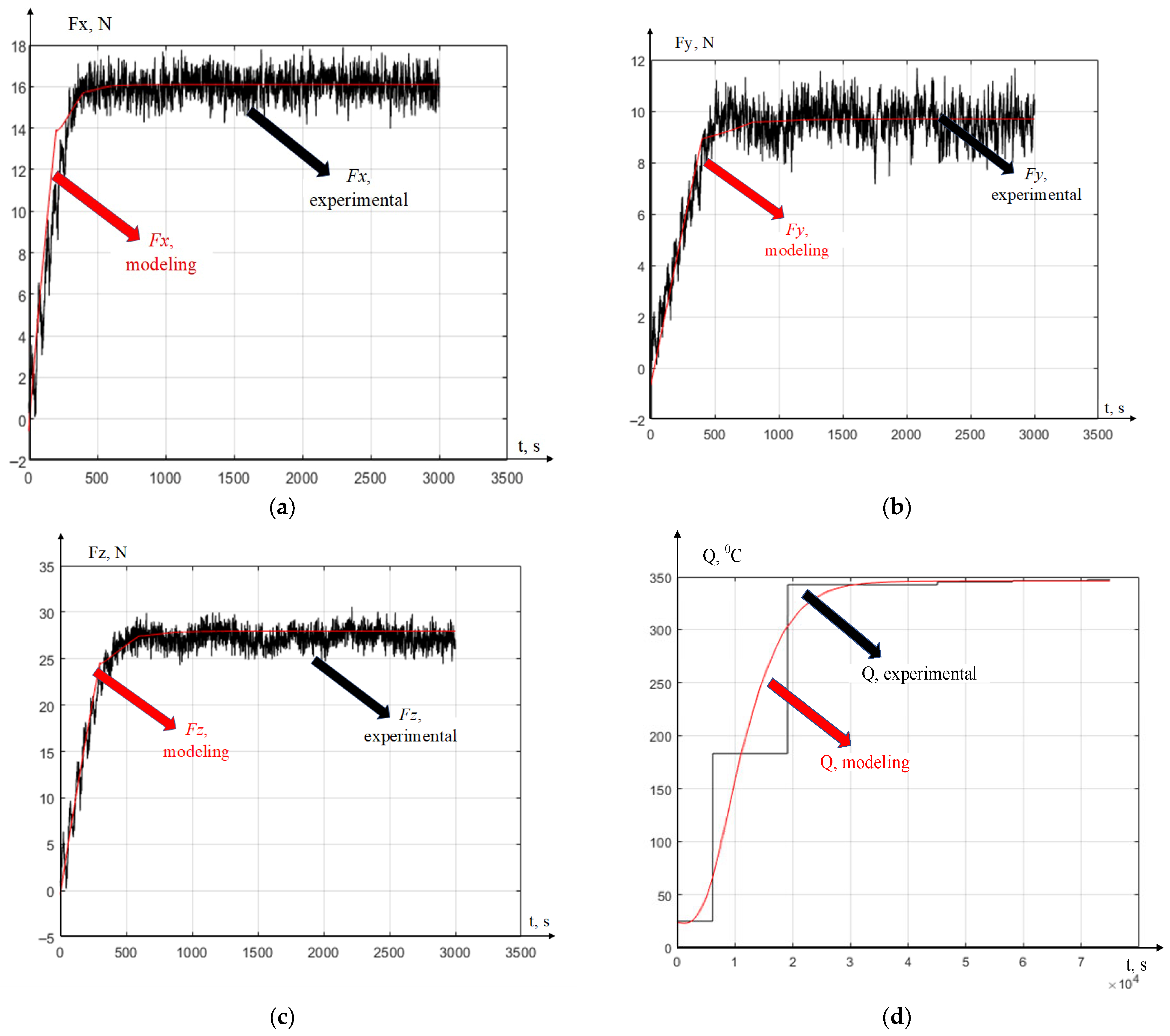

As the first result, we consider the option of turning a part with a wear value of the cutting tool along the back face of 0.15 mm. The results of the processed data obtained in the experiment of cutting forces and temperatures, as well as the results of modeling these same characteristics in the MATLAB 2018 b environment using the system of Equation (13), are shown in

Figure 5. In the experimental studies, the measurement time of the characteristics was equal to 3 s, but since the quantization step is 0.001 s for the case of measuring and modeling forces, the time scale has a dimension of 3500 units, which is 3.5 s of real-time operation of the equipment. The temperature measurements were carried out with a different value of the quantization step of the signal obtained from natural thermal EMF; each second of measurement was 25,000 values, which allowed us to obtain 75,000 specific temperature values in 3 s of the experiment time.

As can be seen from

Figure 5, the comparison of the simulation results and the experimental results shows a high convergence in the field of steady-state values of forces and temperature and a somewhat large discrepancy in the field of the transition process during cutting. The strongest discrepancies are observed in the transient process on the temperature graph; this is due to the high sampling of the measured temperature signal. This discretization of measurements is determined by the features of the measuring complex. The actual graph of temperature rise during cutting will most likely be close to the simulated one, however these are only our assumptions. The time-consuming sampling step of the temperature signal was caused by the limited memory buffer of the measuring system, and we had the following choice: either to reduce the quality of force measurement, or to leave the quality of digitalization of the temperature signal low. Since the measured temperature is almost stable in the steady-state range, this signal was chosen. However, it can be seen from

Figure 5 that the temperature increases smoothly in the transition region, which indicates that the mathematical modeling of this signal is adequate.

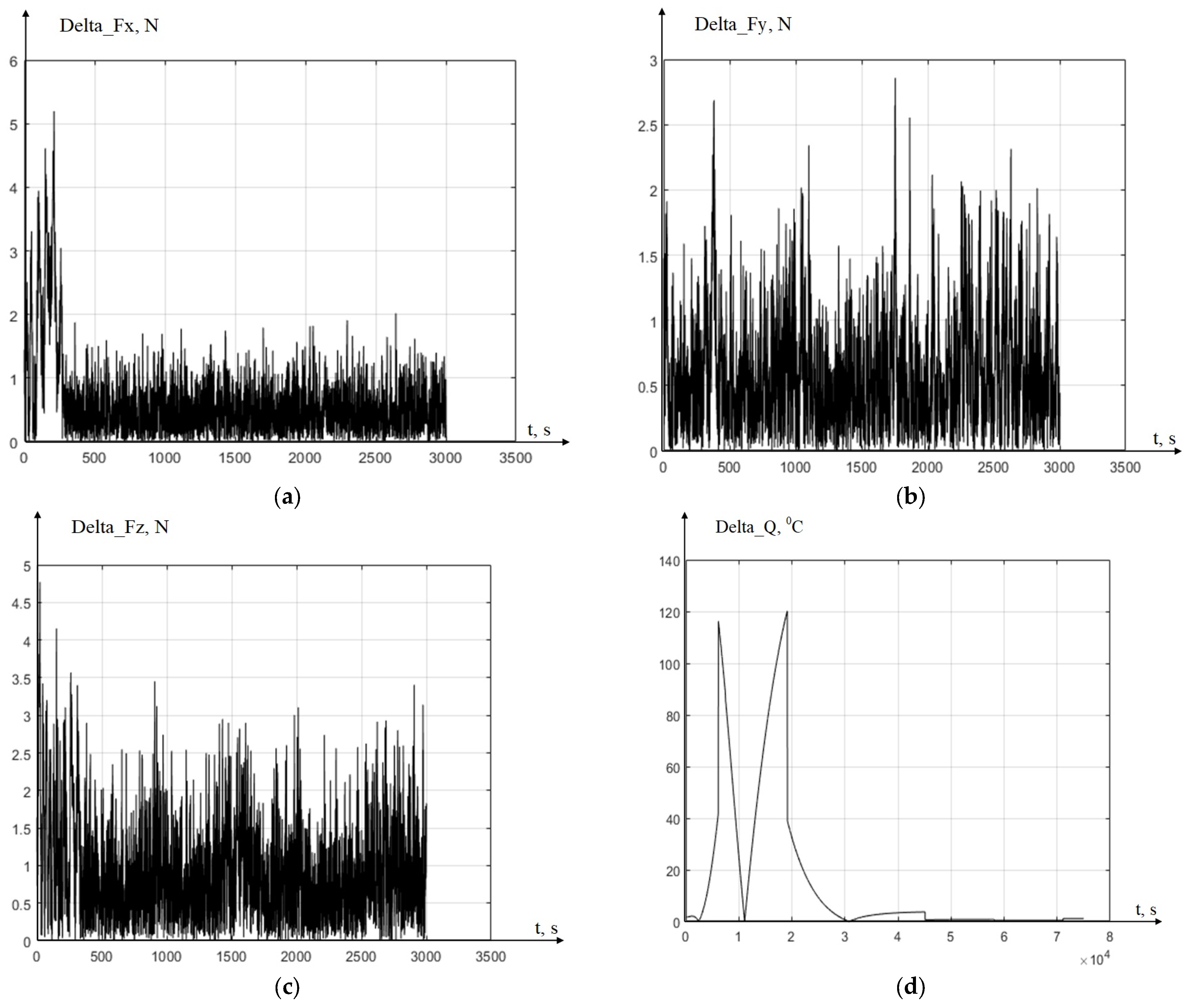

Let us estimate the number of discrepancies for the case under consideration in the form of graphs of the difference between the experimental and simulated signals (see

Figure 6).

As can be seen from

Figure 6, the largest deviations in the graphs can be observed in the first second of measurements, which for the graph of forces has a dimension ranging from 0 to 1000 discrete time values, and on the graph of temperature difference, it ranges from 0 to 25,000 discrete time values. The largest deviation in magnitude is delta_Fx = 5.2 N, delta_Fy = 2.8 N, delta_Fz = 4.77 N, and delta_Q = 120 °C.

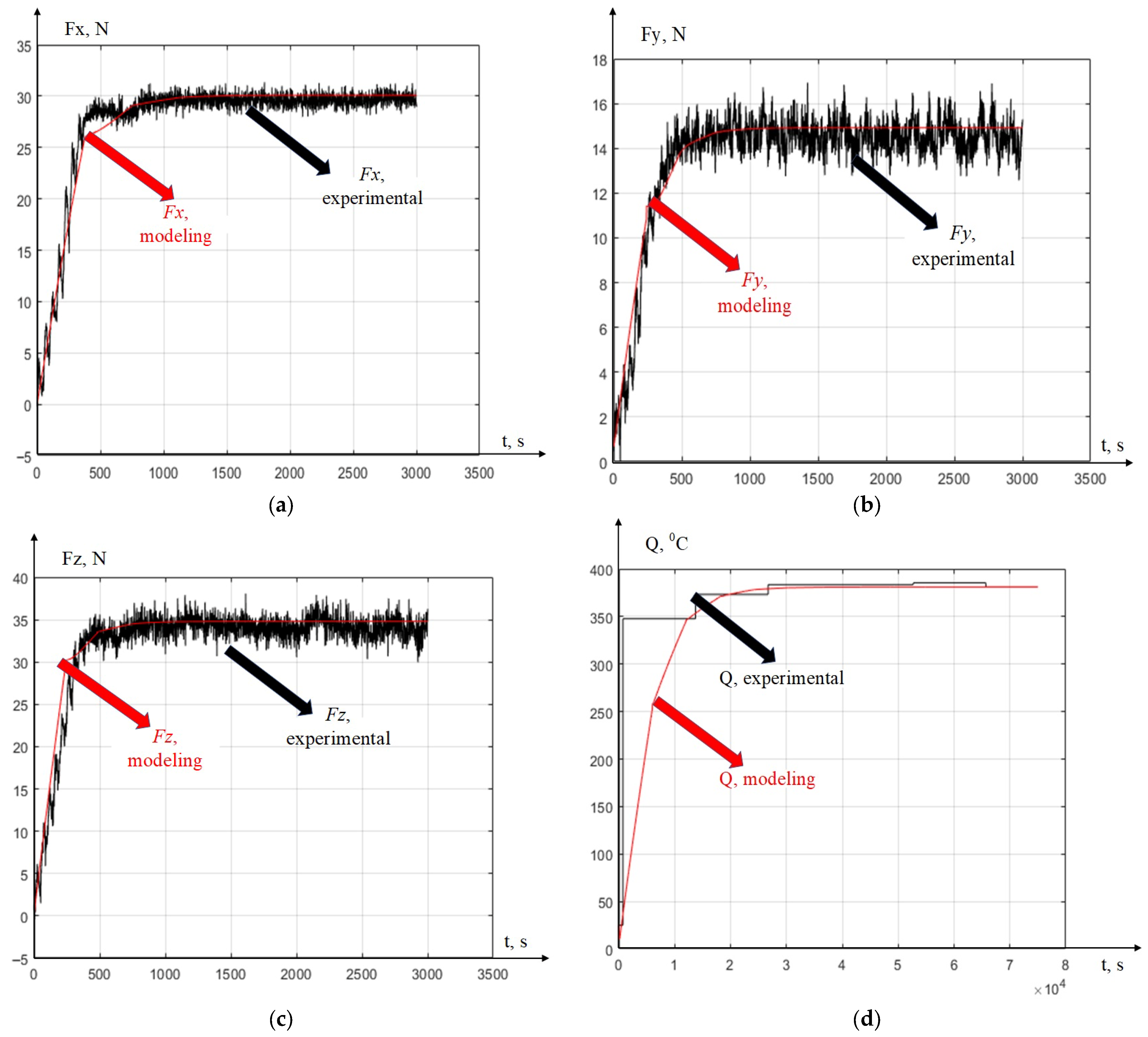

As mentioned above, the presented graphs are only one of the steps in this experiment. To increase the clarity of comparing the results of the experiment and modeling, we consider the case of cutting with a wear value of the cutting wedge along the back face of 0.27 mm (see

Figure 7).

As can be seen from

Figure 7, in the case under consideration, the experimental values of the cutting forces and temperature, which were established after cutting the tool into the part, increased compared to the previous case (see

Figure 5). This growth is explained by the increase in the wear area of the cutting tool along the back edge. The corresponding model characteristics also increased in the range of steady-state values, due to the fact that the wear value of the cutting wedge is included both in the calculated compounding forces and in the calculated temperature value, which is clearly visible in Equation (13). The greatest discrepancy in the dynamics of character change, as well as in the previous case, occurs in the area of the transition process. To quantify this discrepancy, we considered the differences between the measured and calculated values (see

Figure 8).

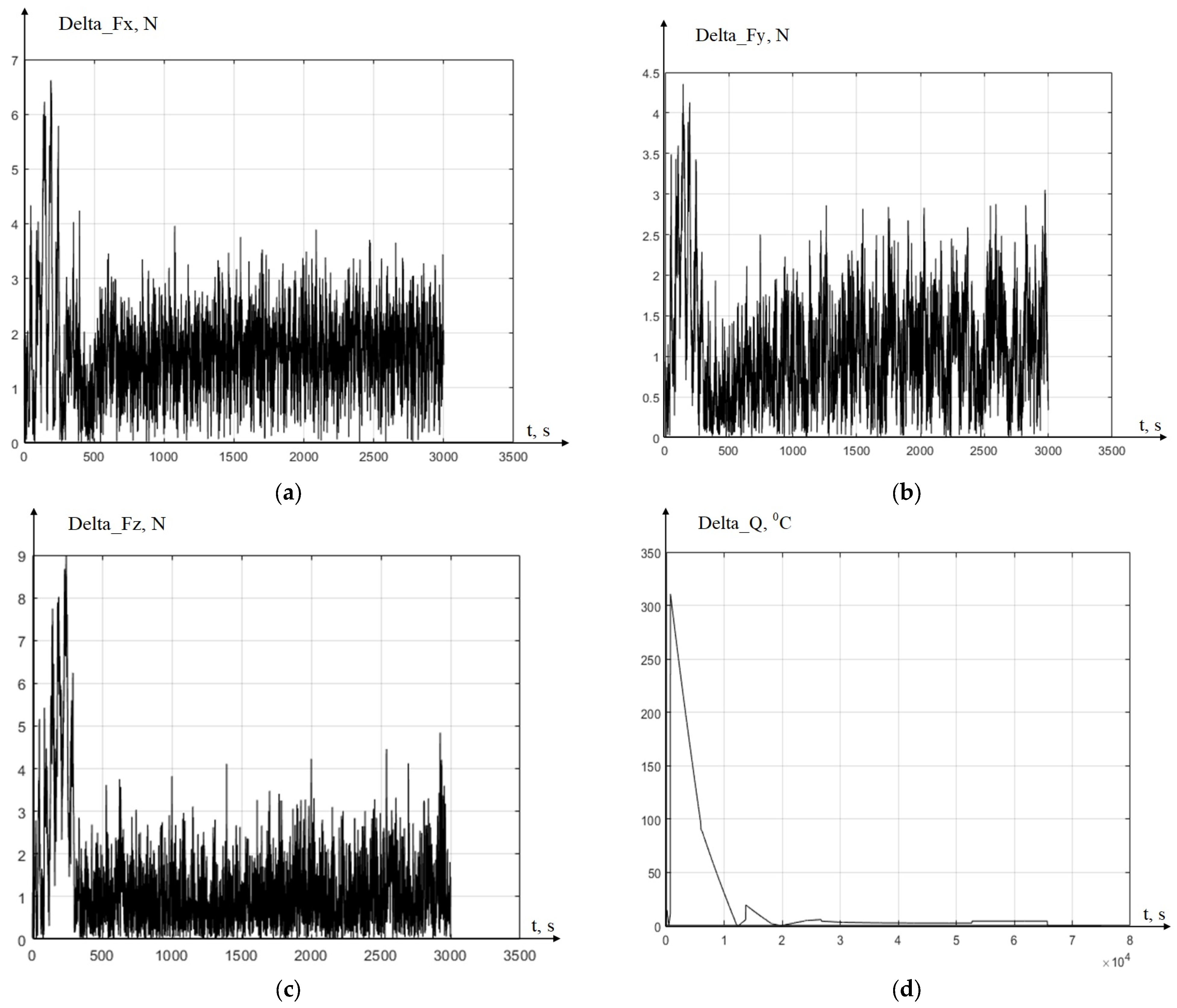

As can be seen from

Figure 8, the values of dynamic mismatches increased. The largest deviation in magnitude is: delta_Fx = 6.6 N, delta_Fy = 4.4 N, delta_Fz = 8.9 N, and delta_Q = 310 °C. However, in the steady state, the misalignments decrease significantly, just as in the previous case.

4. Discussion

As we already mentioned in the introduction, the task of synergetic analysis includes revealing the state space of the cutting process, which is represented through the interaction between the coordinates of the state of this process, and determining the properties of the system. The task of synergetic synthesis is to determine such a set of control parameters available for change, the most important of which is the cutting temperature. The complexity of mathematical modeling, analysis, and synthesis lies primarily in the fact that along the trajectory of the tool relative to the workpiece, the parameters of the mathematical model reveal a change in interactions. This is due to the fact that irreversible energy transformations take place in the cutting system, which irreversibly change the system parameters. The most obvious example of such changes is the irreversible development of tool wear. Irreversible energy transformations, represented by the phase trajectory of the power of irreversible transformations in the work performed, are primarily reflected in the production of heat in various cutting zones. These are, first of all, the zones of primary and secondary plastic deformations, as well as the area of contact between the back face of the tool and the workpiece.

It should be noted that the currently existing ideas about the mathematical description of forces in state coordinates do not take into account the fact that irreversible energy transformations are primarily reflected in heat production. However, the temperature change directly affects the temperature deformations of the tool and the workpiece. To an even greater extent, they affect the parameters of the dynamic coupling formed by the cutting process, which are discussed in the previous paragraphs. They affect the final state of the system by changing the generated chip pressure on the front edge of the tool. They change the dependence of the friction forces on the relative sliding velocity. They contribute to the formation of various dissipative media in the contact zones of the tool faces and the cutting zone. In this regard, the next natural stage in the formation of knowledge about the cutting system, the disclosure of which allows us to build a complete digital analog of the processing process, is the stage of theoretical and experimental studies of the cutting process as an elastic–thermodynamic system. This approach was used in this work. Here, for the first time, a new elastic–thermodynamic view of the formation of virtual models of digital twins is proposed.

The studies presented in the Validation section show that the proposed mathematical model, reflecting the elastic–thermodynamic approach to describing the interaction processes during cutting, has sufficiently high model adequacy. The main discrepancies between the simulated and measured signals are related to the vibration activity of the bearing systems of the 1K625 machine (Uralskaya Mashina, Yekaterinburg, Russia).

The main achievement of modeling the processes of thermodynamic interaction in the cutting system is the high predictive ability of the mathematical model. Indeed, if we do not take into account the transients during cutting but rely on the steady-state values of forces and temperature, then, in the digital twin system, it is possible to predict these values with high accuracy. Based on this, it is possible to calculate in advance the effect of the selected modes on the cutting dynamics. In this regard, the obvious direction for the further development of the proposed elastic–thermodynamic theory of cutting is to determine, from the point of view of dynamics, the optimal cutting modes on metal-cutting machines. It is of interest here to compare the results obtained with already-known works in this field, for example, in the work of Wang H. An idea is given of the mechanism of evolution of subsurface damage to tungsten, which is of great importance for achieving the mechanical processing of tungsten parts with a low level of damage [

25]. However, neither this work nor others like it form a new theory of elastic thermodynamic interaction, but only answer specific questions about specific cases of cutting on individual machines.

The approach proposed in this paper to constructing a finite-dimensional mathematical model of an interconnected cutting system is based on a fairly long study of the thermodynamics of cutting, which is described in the most detail in our earlier work [

26]. It is in this work that the transition from describing temperature in the form of a Voltaire operator of the second kind to a finite-dimensional differential equation was experimentally substantiated. Based on this, we did not focus on this replacement in our current work.

5. Conclusions

This paper reveals the main approaches to the synthesis of a mathematical description of the processes occurring during metal-cutting on metal-cutting machines. This synthesis contains a new, previously unused approach to furnish the description of the thermo-dynamics of the cutting process. The classical mathematical model of interactions during cutting is supplemented here by a description of the thermodynamic interaction, which is an integral part of the entire system of interactions arising during cutting. The thermodynamic interaction is represented as the sum of two temperature phenomena, the first of which is caused by the conversion of the power released in the cutting area into temperature, and the second is associated with the formation of a contact area on the back of the cutting tool, through which the heat released in this contact earlier is transferred to the future cutting area in one revolution before the current cutting. The mechanism of temperature transfer from the previous cutting stages to the current cutting zone identified here is called thermodynamic feedback, which significantly affects the interactions in the cutting system. For the first time, a proposed mathematical model describing the evolutionary nature of the formation of thermodynamic feedback of the cutting process makes it possible to link the thermodynamics of the cutting process with changes in the wear of the cutting tool.

In addition to the synthesis of the mathematical apparatus, a series of experiments was carried out on a 1K625 lathe, the results of which were used to compare experimental and simulated characteristics. A comparison of the results allows us to conclude that modeling the dynamics of the cutting process on metal-cutting machines is sufficiently adequate based on the proposed theory of elastic–thermodynamic interaction.

Note that the goals set at the beginning of the work have been achieved, and all the tasks set have been solved.