1. Introduction

Bio-inspired flapping-wing micro aerial vehicles (FW-MAVs) draw inspiration from the flight mechanisms of birds and insects, offering unique advantages that set them apart from fixed-wing and rotary-wing counterparts. These vehicles are characterized by their portability, high safety, stealth, and minimal environmental disturbance, making them highly suitable for applications such as search and rescue missions or environmental monitoring.

To date, numerous bird-inspired flapping-wing air vehicles with tail wings have been developed [

1]. These vehicles utilize tail surfaces for passive stabilization and control moment generation, enabling effective operation in open spaces with demonstrated high payload capacity [

2] or long endurance [

3,

4,

5]. However, this reliance on aerodynamic tail surfaces inherently precludes hovering and limits agility, making such designs unsuitable for navigation in confined or cluttered environments. This fundamental trade-off highlights the divergent design paradigms in tailed flapping-wing MAVs: tailed platforms are optimized for efficient forward flight at the expense of maneuverability in tight spaces.

In contrast, tailless FW-MAVs draw inspiration from flying insects [

6,

7,

8], which achieve extraordinary agility and hovering in confined spaces. By eliminating tail surfaces and relying solely on active modulation of wing kinematics for both lift and attitude control, tailless designs inherently enable full six-degree-of-freedom (6-DOF) flight, including sustained hovering. This capability comes at the cost of inherent instability, necessitating active feedback control, but confers critical advantages: superior disturbance rejection, enhanced maneuverability, and the ability to operate effectively in complex environments such as forests, ruins, and indoor spaces. Yet, this paradigm has historically been hampered by severely limited endurance and payload capacity. Bridging this gap—developing a tailless FW-MAV that retains agile hovering while achieving long endurance and high payload—remains a pivotal challenge and is the central objective of this work.

To date, only a limited number of tailless FW-MAVs have demonstrated the ability to achieve free flight for several minutes [

9,

10,

11]. Among these, DARPA’s Nano Hummingbird was the first tailless FW-MAV capable of onboard battery-powered free flight [

12]. It employed a string-based flapping mechanism and had a total weight of 19 g. Attitude control was achieved using three servos that adjusted the tension or relaxation of the wings, enabling a maximum endurance of 11 min (Saturn version). The KUBeetle-S employs a control concept of wing twist modulation for attitude stabilization [

13]. By utilizing low-voltage batteries and lightweight servos, its performance was significantly improved compared to earlier versions [

14]. The weight was reduced from 21 g to 15.8 g, and the flight endurance increased from 3 min to 8.8 min. Subsequent iterations of the KUBeetle-S incorporated advanced features such as collision recovery mechanisms, as well as passive wing deployment and retraction [

15,

16]. Delft University’s Nimble, weighing 29 g, controlled body attitude by altering the stroke plane center of the wings, achieving a flight time of 5 min [

17]. Its commercial version, Nimble+, with a minimum weight of 102 g, can sustain flight for 8 min [

18]. The Festo BionicBee employs a brushless motor to drive the wings, with three servos controlling the wing trailing edges to generate attitude control moments [

19]. It achieves a flight time of 4 min. The NUS-Roboticbird features two motors driving four wings [

20]. It utilizes stroke plane adjustment to generate attitude control torques. With a weight of 31 g, it can achieve 4 min of flight without a payload or 3.5 min while carrying a camera. Quadthopter with four pairs of wings utilized four motors to drive four independent flapping mechanisms, relying on motor speed differences to generate attitude control moments [

21]. With a weight of 37.9 g, it achieved a flight endurance of 9 min.

Notably, none of these tailless FW-MAVs have surpassed 15 min of flight endurance, significantly limiting their ability to perform extended missions. This highlights the challenges faced in enhancing the endurance and operational capabilities of tailless FW-MAVs.

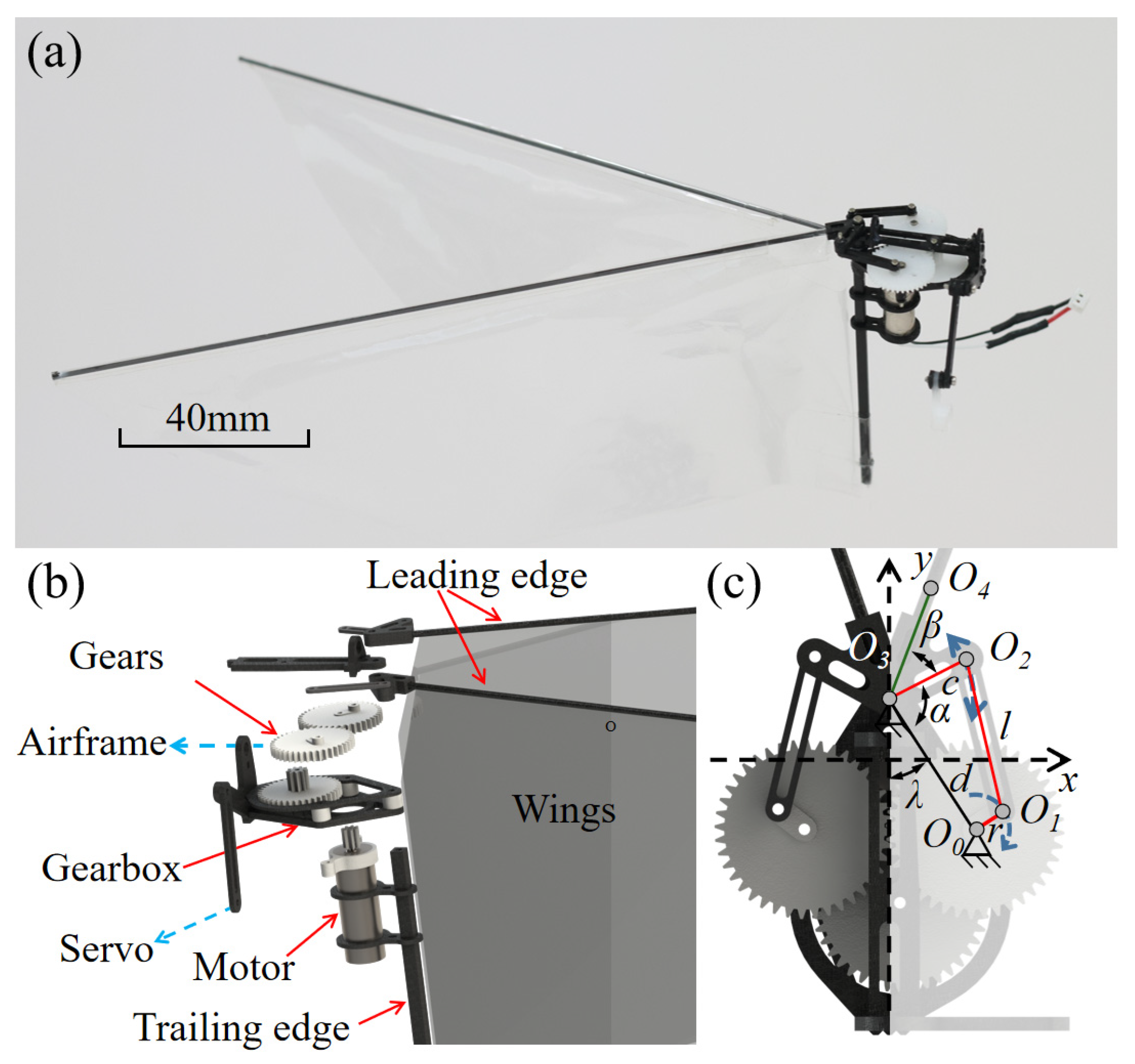

This work aims to significantly enhance the flight endurance and payload capacity of tailless FW-MAVs. To this end, we focus on the design of a lightweight flapping mechanism with a high thrust-to-weight ratio. Each flapping mechanism employs a crank-rocker design to drive a pair of wings that oscillate in opposite directions, effectively canceling lateral vibrations. This design offers a high lift-to-power ratio and ensures reliability. This tailless FW-MAV is named X-fly. As shown in

Figure 1, the X-fly platform incorporates two flapping mechanisms with four wings, enabling attitude control by altering the stroke plane of each mechanism using two servos to adjust lift vector direction. We experimented with various stroke amplitudes and wing configurations to optimize lift performance. The current X-fly configuration features a 36 cm wingspan and a net weight of 18.9 g (excluding the battery). When equipped with a commercially available 1100 mAh battery, the takeoff weight is 40.5 g, and it achieves a maximum flight endurance of 33.2 min. With a 250 mAh battery, it can carry a payload equal to its own weight of 18.9 g. The platform recovers from disturbances within 0.4 s, achieving a maximum forward flight speed of 5.35 m/s and a lateral flight speed of 6 m/s. Additionally, it can be equipped with a first-person-view (FPV) camera for beyond-visual-line-of-sight operations. Our tailless FW-MAV represents a significant advancement in flight endurance and payload capacity. It serves as a robust platform for future autonomous flight and mission execution, laying the foundation for the deployment tailless FW-MAVs equipped with payload devices for various applications.

3. Experimental Section

Following the design of the flapping and control mechanisms, a series of experiments were conducted to validate their performance and optimize key parameters. To achieve the X-fly with high maneuverability, long endurance and high payload capacity, in addition to the aforementioned design of lightweight crank-rocker flapping mechanism with high thrust-to-weight ratio, optimizing the wing design and adopting robust control methods are also essential. In this section, the wing length and flapping angle were optimized through experiments, and the flight attitude stability control design was verified by experiments.

3.1. Optimization of Flapping Angle and Wing Length Through Experiments

3.1.1. Experiment Setup

To achieve higher lift, a series of experiments were conducted to evaluate the lift generation and power requirements of wings with different flapping angles and wing lengths. As shown in

Figure 4a, an external power supply (UNI-T UDP3305S-E, China) was used to drive the flapping mechanism, and the input voltage and current were recorded. A single flapping mechanism was mounted on a six-axis force/torque (F/T) sensor (ATI Nano17, range: ±25 N for forces, ±250 N·mm for torques; resolution: ≈0.006 N for forces, ≈0.03 N·mm for torques). The sensor was mounted via a custom-designed adapter, and data were acquired at a sampling frequency of 3000 Hz using ATI DAQ F/T software (Version: 2.1.8460.26505). This high-frequency sampling ensured accurate capture of the dynamic lift profiles generated by the flapping mechanism.

As illustrated in

Figure 4b, two flapping mechanisms with flapping angles of 40° and 47° were designed. The angle selection was informed by reported work on bio-inspired flapping-wing micro air vehicles, including the Delfly Nimble [

26], the Nimble+ [

18], and X-wing ornithopter [

23]. The flapping angle range of 40–50° represents typical kinematic parameters for efficient X-wing flapping-wing vehicles. The optimal stroke amplitude may vary slightly across different configurations, influenced by factors such as motor output power, wing shape and inertia, and mechanical structure, which are ultimately determined by the flapping mechanism design. Therefore, experiments were conducted using the smaller angle of 40° and the larger angle of 47° as baseline values. Additionally, three sets of wings with lengths of 13.5 cm, 15 cm, and 16.5 cm were tested under identical wing widths (

Figure 4c). During the experiments, the flapping frequency was controlled by varying the input voltage of the external power supply within a range of 2 V to 3.8 V.

Referring to study [

23] that validated the high efficiency of flapping-wing mechanisms through comparative analysis with traditional rotor-based propulsion, we selected three commercially available propellers with diameters of 35 mm, 42 mm, and 45 mm (

Figure 4d), each of which was mounted on a motor of the same specifications as those used in the flapping-wing mechanism. The selected motor-propeller combination is widely adopted in various small-scale quadrotors, ensuring its reliability and relevance for comparative analysis. In the experimental setup (

Figure 4e), each motor-propeller assembly was mounted on a six-axis F/T sensor via a custom adapter. Lift generation, power consumption, and lift-to-power ratio (LPR) were measured under controlled conditions. To eliminate ground effect interference, all tests were performed on an elevated platform.

For the propeller tests (

Figure 4e), we mounted each motor-propeller assembly on the six-axis F/T sensor using a custom adapter. To eliminate ground effect, all lift tests were performed on an elevated platform.

3.1.2. Experiment Results

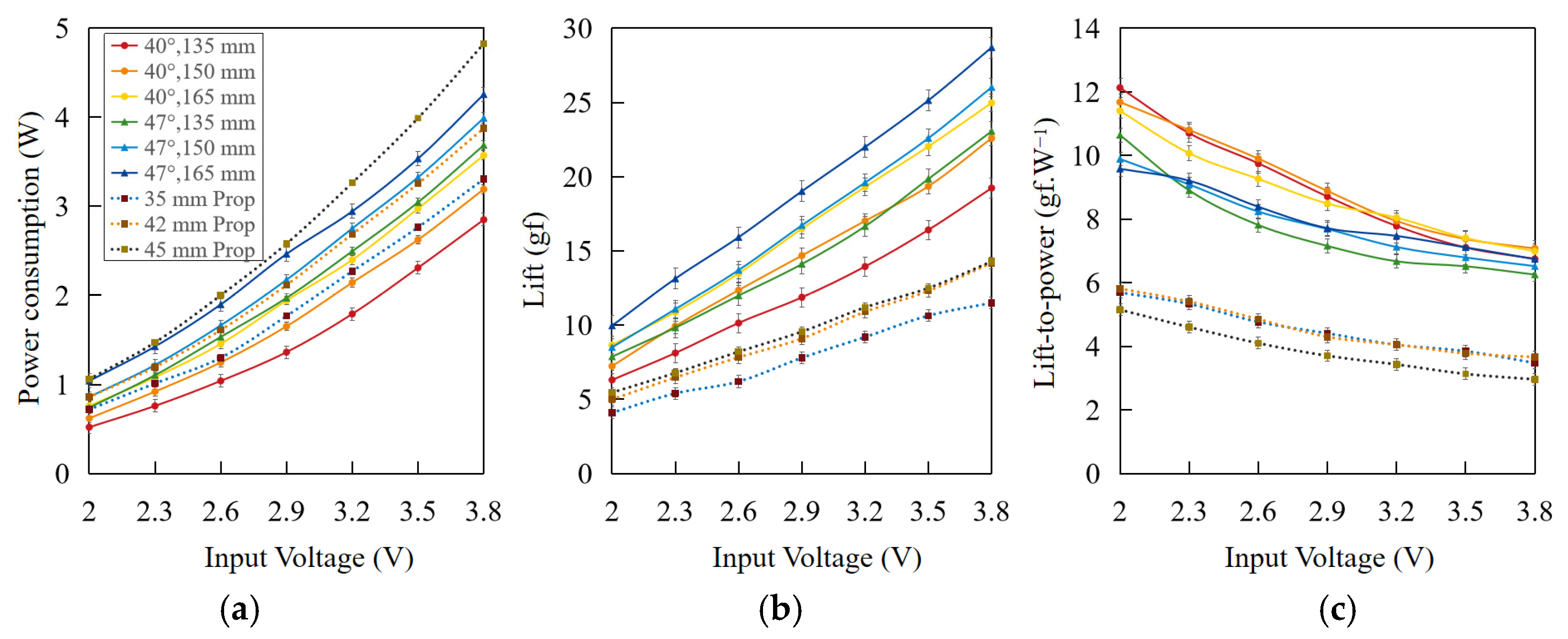

Figure 5a depicts the relationship between power consumption and input voltage. The data reveal that larger flapping angles and greater wing lengths result in higher power consumption. At 3.8 V input voltage, the 165 mm wing length and 47° flapping angle combination exhibited a maximum power consumption of 4.3 W. In comparison, the 45 mm propeller-motor combination consumed 4.8 W.

Figure 5b illustrates the relationship between lift and input voltage. The results indicate that larger flapping angles and greater wing lengths significantly enhance lift generation. The combination of a 165 mm wing length and a 47° flapping angle achieved the highest lift, producing a maximum of 28.7 gf at 3.8 V input voltage, with a lift-to-power ratio of 6.67 gf/W. In contrast, among the tested propeller setups, the 45 mm propeller-motor combination generated a maximum lift of 14.2 gf at 3.8 V, which is only 49% of the lift produced by the flapping-wing configuration.

Figure 5c presents the relationship between the lift-to-power ratio and input voltage. Regardless of configuration, both flapping-wing and propeller setups showed a decreasing lift-to-power ratio as the input voltage increased. Among the flapping wing configurations, the 40° flapping angle exhibited the highest lift-to-power ratio. Furthermore, all flapping-wing setups demonstrated significantly better lift-to-power ratios compared to the propeller setups.

The experimental results highlight that, for a given flapping angle, wings with larger wing lengths generate higher lift at the same input voltage. Although the 40° flapping angle configuration provides a superior lift-to-power ratio compared to the 47° configuration, the 47° flapping angle achieves higher lift at lower input voltages, making it advantageous for applications requiring maximum lift generation.

Higher lift at lower input voltages allows the FW-MAV to carry a higher capacity battery and continue flying until the battery is completely discharged. Based on the results of the lift experiments, the configuration with a 165 mm wing length and a flapping angle of 47° was identified as the optimal setup for achieving extended flight endurance. This combination effectively balances lift generation and power efficiency, enabling the vehicle to maximize its flight duration.

3.2. Attitude Stability Control Test

With the flapping mechanism optimized for lift and efficiency, the next critical step is to ensure stable and controllable flight. Unlike conventional FW-MAVs that achieve passive stability through tail wings, tailless FW-MAVs rely on flapping mechanisms and control actuators to generate control torques, enabling active stabilization via the flight control system. This design allows the vehicle to quickly recover attitude stability after external disturbances. Quantifying these torques and conducting stability disturbance tests are therefore essential to optimize flight performance and enhance maneuverability under real-world conditions.

3.2.1. Measurement of Flight Attitude Control Torques

The experimental setup for torque measurement is depicted in

Figure 6. The F/T sensor (Nano17) was mounted near the vehicle’s center of mass using a custom adapter, the “+” denotes the positive direction of the torque. To maintain a total vertical lift of approximately 42 gf (The lift required to hover), the input voltages to the left and right flapping mechanisms were independently controlled by two external power supplies. Additionally, two servo controllers were used to adjust the stroke planes of the wings, enabling oscillation angles between −15° and 15°.

Figure 7a illustrates the yaw control torque tests, where the stroke planes on both sides were tilted in opposite directions. As the tilt angle varied between −15° and +15°, the yaw torque

Mz ranged from −7.4 N·mm to 6.8 N·mm.

Figure 7b depicts the pitch control torque tests, in which the pitch torque

My was adjusted by tilting the stroke planes of both wings in the same direction. When the control input angle changed from −15° to +15°, My varied from −6.1 N·mm to 5.5 N·mm.

Figure 7c shows the roll control torque tests, where different input voltages were applied to the left and right wing mechanisms to generate varying lift forces for each wing, while maintaining a constant total lift. As the voltage difference ranged from −1.2 V to +1.2 V, the roll torque

Mx transitioned from −8.1 N·mm to +9.3 N·mm.

3.2.2. Test for Flight Attitude Stabilization Control

Figure 8 illustrates the flight attitude control system architecture of the X-fly. The system employs PID-based angle controllers and PID-based angular rate controllers to perform attitude adjustments. Feedback signals for pitch, roll, and yaw—derived from an IMU through a sensor fusion algorithm—are used to regulate the servos and motors within the attitude control loop. This control architecture is implemented to ensure robust stabilization of the vehicle’s attitude, compensating for external disturbances and maintaining desired flight trajectories. The control parameters are selected as in

Table 1, where the parameter values have been normalized.

The electronic system configuration of the X-fly is illustrated in

Figure 9. The autopilot board [

27], weighing 2.1 g, integrates a 32-bit Cortex-M4 MCU (STM32F446ME) controller, an inertial measurement unit (IMU), wireless communication circuitry, two low-dropout (LDO) regulators, a DC-DC boost converter, two motor drivers, and an SPL06 barometric pressure sensor. The printed circuit board (PCB) has dimensions of 24 mm × 19 mm × 4 mm.

We validated the feasibility of the attitude control system through a series of continuous flight tests. The X-fly’s hovering and multi-degree-of-freedom flight capabilities were tested via remote control, and its performance in hovering, forward flight, turning, and lateral flight was evaluated within a Vicon motion capture system composed of eight infrared motion capture cameras.

Figure 10 illustrates the flight trajectories recorded during the tests, while

Figure 11 presents the corresponding attitude data. During hovering, the X-fly maintained stable suspension within a range of ±15 cm in the forward/backward, left/right, and upward/downward directions under operator control, with attitude fluctuations along all axes remaining within ±5°. Forward flight was achieved through pitch control, and within 2 s, it covered a distance of 1.7 m while performing both acceleration and deceleration maneuvers. Turning was accomplished via yaw control, completing a 450° rotation within 5.4 s. Finally, lateral flight was realized through roll control, covering a distance of 1.9 m in 2.4 s.

To evaluate the X-fly’s ability to recover from disturbances, a throw-and-stabilize test was conducted. The vehicle was manually launched from a height of approximately 1.2 m with an initial horizontal velocity of about 1 m/s. To induce a significant attitude perturbation, it was released with an initial angular impulse that caused it to undergo a full 360° uncontrolled roll in the air. As shown in

Figure 12 and

Supplementary Video S1, the X-fly was manually thrown into the air with an initial uncontrolled rolling motion. During the uncontrolled descent, the operator engaged the throttle, activating the attitude control system. The vehicle promptly recovered and transitioned to stable hovering.

Figure 13 presents the attitude data recorded during the throw-and-stabilize test. At

t = 0 s, the vehicle was released by hand, experiencing significant angular rolling. By

t = 0.4 s, the vehicle had successfully stabilized from the uncontrolled state and achieved stable hovering. This demonstrates the vehicle’s robust attitude stabilization capability, which is crucial for reliable operation in dynamic and unpredictable environments.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the X-fly’s flight endurance test, stabilization test, maximum load test, fast flight test, and maneuverability test. Furthermore, equipped with an FPV camera, the X-Fly comprehensively demonstrated its target search capability in a simulated forest environment.

4.1. Flight Endurance

The weight breakdown of the X-fly is shown in

Figure 14. The weight of the flapping mechanisms on both sides (

Figure 2a for one side) is 9.2 g. As described in

Section 3.1, they can generate a peak lift of 57.4 gf at 3.8 V with a peak lift-to-weight ratio of 6.24. The X-fly’s net weight excluding the battery is 18.9 g and its peak lift-to-weight ratio is 3.04. Benefiting from its high lift-to-weight ratio, the X-fly can carry a larger proportion of its weight as the battery, enabling extended flight durations.

To evaluate the practical endurance capability of the X-fly, an endurance test was conducted indoors within a confined 4 × 4 × 4 m

3 space. The X-fly was equipped with a 21.6 g, 1100 mAh, 4.18 Wh lithium battery (Gaoneng GNB) with an energy density of 193.5 Wh/kg. Under these conditions, the X-fly had a total takeoff weight of 40.5 g and demonstrated a peak lift-to-weight ratio of 1.42 at 3.8 V. The X-fly was manually controlled by an operator and hovered in front of a timer until the battery was depleted and further flight was no longer possible. All flights were recorded using a DJI Action camera. The experiment was repeated three times, yielding an average endurance of 32.5 min. The longest flight recorded in these experiments reached 33.2 min, and its composite image is shown in

Figure 15, as detailed in

Supplementary Video S1.

Figure 16 compares the X-fly to several other typical tailless FW-MAVs in terms of weight and endurance. The X-fly’s flight endurance significantly outperforms these other FW-MAVs, tripling the longest previously reported endurance time (namely, 11 min of the Nano Hummingbird).

4.2. Maximum Load

Beyond endurance, the high lift-to-weight ratio of the X-fly also translates into a significant payload capacity. A greater lift-to-weight ratio not only enables extended endurance by accommodating larger capacity batteries but also allows for a significantly higher payload capacity. To evaluate the X-fly’s maximum payload capacity, it was equipped with a smaller 5.5 g, 250 mAh lithium battery (Gaoneng GNB, 0.95 Wh). In this configuration, as shown in

Figure 17a and

Supplementary Video S1, the X-fly successfully carried an additional X-fly without its battery, corresponding to a payload of 18.9 g, which is equivalent to 100% of the X-fly’s net weight. The corresponding body attitude data during the payload-carrying flight are presented in

Figure 17b. During a 25 s payload flight test, the shift in the center of gravity induced by the payload did not noticeably compromise flight stability. Roll and yaw angles maintained stability comparable to that of unloaded flight (the hovering phase shown in

Figure 11), with oscillation amplitudes remaining within ±5°. Although the pitch oscillation amplitude increased compared to unloaded flight due to the altered center of gravity, it was still confined within ±8°, thereby enabling sustained and stable flight. This configuration achieved sustained free flight with a total takeoff weight of 43.3 g, and the X-fly demonstrated a peak lift-to-weight ratio of 1.32 at 3.8 V, confirming its ability to handle substantial payloads relative to its own weight.

This high payload capacity makes it possible for the X-fly to integrate more sensors for diverse environmental data collection or use more powerful computational chips to achieve advanced functions, such as onboard autonomous navigation, decision-making, and complex data processing. These capabilities establish the X-fly as a reliable platform for future applications, including search-and-rescue missions and environmental monitoring, where sufficient payload capacity and controllability while carrying loads are indispensable.

Table 2 presents a performance comparison of representative flapping-wing aerial vehicles (FW-AVs). Bird-inspired, tailed FW-AVs (e.g., E-Flap, NPCXinge) still exhibit significant advantages in endurance and payload capacity. However, their inability to hover limits their operational utility in confined or complex spaces. In contrast, tailless FW-MAVs, while capable of hovering and agile maneuvering, have generally been constrained by short endurance (typically not exceeding 15 min) and limited payload capacity, which substantially restricts their practical application in extended real-world missions. Among tailless FW-MAVs, the X-fly represents a notable breakthrough in both endurance and payload capability. With an 1100 mAh battery and a takeoff weight of 40.5 g, it achieves a flight endurance of 33.2 min, significantly surpassing existing tailless platforms (e.g., 11 min for the Nano Hummingbird). When equipped with a 250 mAh battery, it can carry an additional payload equal to its own net weight (18.9 g). This performance not only extends the mission duration and capability of tailless FW-MAVs but also establishes a solid platform for integrating additional sensors or computational units to enable more advanced autonomous functions.

4.3. Fast Flight

The maximum flight speed is a critical parameter for evaluating the efficiency of the FW-MAV during mission execution. A higher flight speed also enhances the vehicle’s wind resistance. To measure the X-fly’s maximum flight speed, experiments were conducted outdoors under calm conditions (wind speed < 0.2 m/s). Four flags spaced 2 m apart were used as distance markers, and the experiment was recorded using a Canon R7 camera at 50 fps. The tests assessed both the maximum forward flight speed achieved through pitch-axis control and the maximum lateral flight speed achieved through roll-axis control. As shown in

Figure 18a and

Supplementary Video S1, forward flight was achieved by pitch control, where the vehicle adjusted its flapping stroke plane angle to tilt forward. Experimental results demonstrated that the X-fly completed a 6 m flight in 1.12 s, achieving a forward speed of 5.35 m/s. As illustrated in

Figure 18b and

Supplementary Video S1, lateral flight was achieved through roll control, wherein the lift difference between the two flapping-wing mechanisms generated a rolling moment. The results showed that the X-fly completed the 6 m lateral flight in 1 s, achieving a lateral speed of 6 m/s.

4.4. Maneuverability Test

Unlike traditional flapping-wing vehicles with tail wings, which require relatively large operating spaces, the tailless FW-MAV demonstrates exceptional agility, enabling it to maneuver effectively in confined spaces. To evaluate the X-fly’s flight capability in complex environments, a maneuverability test was conducted in a forested area. The experiment required the X-fly to fly in a figure-eight pattern around two trees, simulating flight in a cluttered and constrained environment. During the test, the vehicle needed to avoid disturbances caused by leaves and underbrush, which posed significant challenges to its attitude stability and controllability. The X-fly was controlled by an operator and successfully completed the figure-eight flight, demonstrating its precise maneuverability and robustness in confined spaces.

Figure 19 presents a composite image capturing the X-fly’s trajectory while performing the figure-eight flight between two trees, as detailed in

Supplementary Video S1. This test highlights the X-fly’s strong attitude stability and high controllability, validating its potential for operations in narrow and obstacle-filled environments.

4.5. Application Scenario Demonstration

The tailless control system enables the FW-MAV to achieve hovering and agile maneuvering, allowing it to navigate through narrow spaces and reach designated locations to perform tasks. To demonstrate the potential application of the X-fly in search-and-rescue missions, we designed a simulated scenario, as shown in

Figure 20 and

Supplementary Video S1. In this experiment, a balloon was used as a surrogate victim to simulate a trapped individual and was placed deep within a forested area as the target. The X-fly was equipped with a commercial FPV camera weighing 3.2 g that includes a 25 mW 2.4 GHz video transmitter. These components shared a single 850 mAh battery with the flight system. The camera transmitted live video feeds to a video receiver, enabling remote operation and target identification by the operator. During the experiment, the X-fly was remotely controlled by an operator to navigate through the forest while searching for the surrogate victim. Once the onboard camera captured the image of the target, the X-fly hovered near the target to confirm its identity. Upon successful identification, the search-and-rescue mission was considered complete. This experiment highlights the X-fly’s capability to perform tasks in complex environments and its potential for search-and-rescue applications.

5. Conclusions

This article presents the design, development, and experimental validation of a tailless flapping-wing micro aerial vehicle (FW-MAV) named X-fly, which achieves significant improvements in both flight endurance and payload capacity. The vehicle incorporates lightweight crank-rocker flapping mechanisms with high thrust-to-weight ratios. Through systematic optimization of wing geometry and stroke kinematics, a single 4.6 g flapping module generates up to 28.7 gf of lift. By employing two independent flapping modules and modulating their stroke planes via servo actuation, the X-fly attains full attitude control, enabling stable hovering, six-degree-of-freedom free flight, and rapid recovery from external disturbances within 0.4 s.

In terms of performance, X-fly reaches a maximum flight endurance of 33.2 min using a commercially available 1100 mAh battery—tripling the best previously reported endurance for tailless FW-MAVs. When equipped with a smaller 250 mAh battery, it can carry an additional payload equal to its own net weight (18.9 g). The vehicle achieves forward and lateral flight speeds of 5.35 m/s and 6 m/s, respectively, demonstrating high agility and wind tolerance.

Practical feasibility is confirmed through field tests in constrained environments: X-fly successfully executed figure-eight maneuvers around closely spaced trees and, when fitted with an onboard FPV camera, a simulated search-and-rescue mission was demonstrated by identifying a target in a forested area. These results underscore its potential for real-world applications such as search and rescue, environmental monitoring, and reconnaissance.

Looking forward, X-fly serves as a versatile platform for integrating advanced sensors and high-performance computing units to enhance autonomous capabilities. Further integration with multi-modal mobility modules could extend its operational scope. This work lays a solid foundation for the development of next-generation FW-MAVs with extended mission endurance, improved payload accommodation, and robust performance in complex, cluttered environments.