Robust Optimal Consensus Control for Multi-Agent Systems with Disturbances

Highlights

- A novel improved nonlinear extended state observer (INESO) is designed to achieve real-time estimation of unknown disturbances in multi-agent systems (MASs), significantly enhancing system robustness through an effective compensation mechanism.

- A momentum-accelerated Actor–Critic network is developed that substantially improves convergence speed and suppresses unstable oscillations during multi-agent consensus.

- The proposed distributed optimal disturbance rejection control protocol provides a scalable solution for nonlinear MASs under unknown disturbances, overcoming the inherent trade-off between convergence rate and stability in existing methods.

- This framework establishes a reliable technical foundation for UAV swarm applications in search and rescue, logistics, and inspection missions, demonstrating improved cooperative stability in disturbed environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A novel improved nonlinear extended state observer (INESO) is designed to realize the real-time estimation of the unknown disturbances of DT-MASs. The unknown disturbances are effectively handled by a compensation mechanism, and the robustness of the systems is significantly improved.

- A momentum-accelerated Actor–Critic network is developed for DT-MASs to accelerate state convergence and suppress unstable behaviors. The problem of a slow convergence rate of the standard gradient descent method is effectively overcome by historical gradient information, and the state convergence time is shorter for DT-MASs to achieve stability.

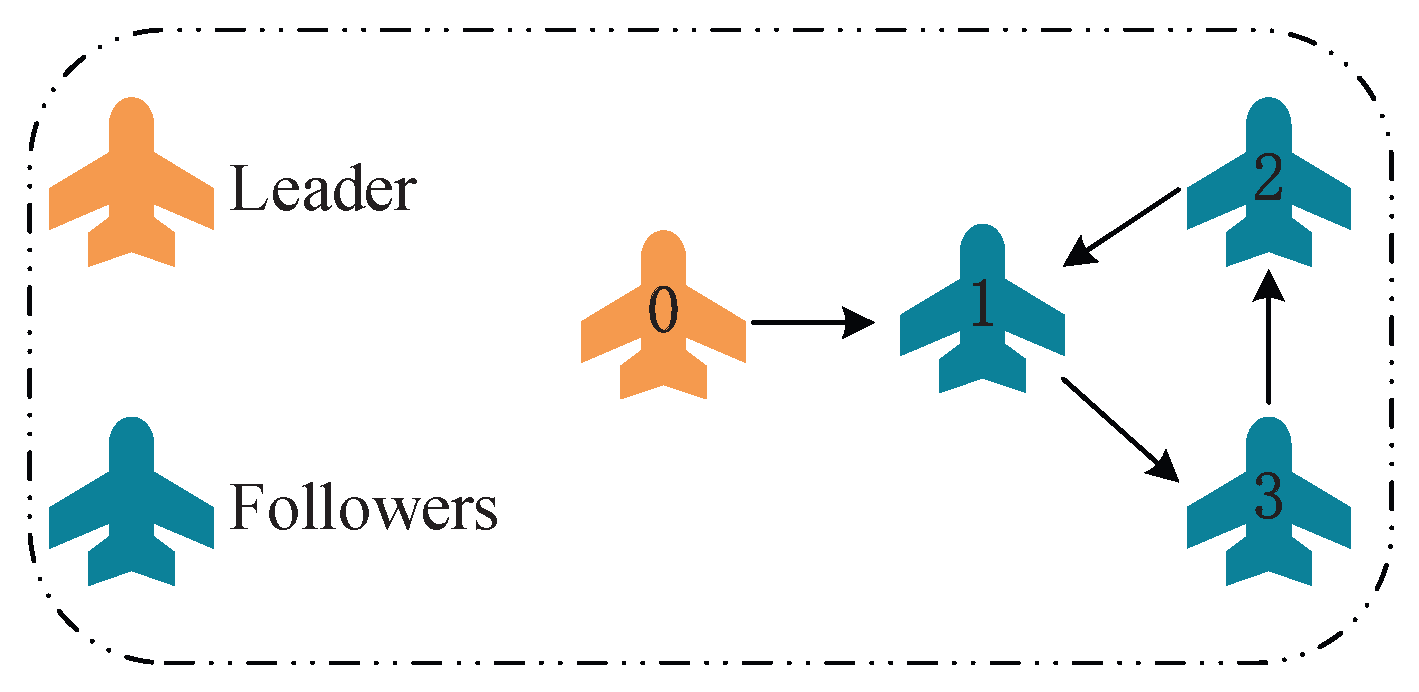

- A distributed optimal disturbance rejection consensus control protocol is proposed for DT-MASs subject to unknown disturbances to reach consensus. Relying solely on local neighbor interactions, this protocol guarantees scalability to arbitrarily large-scale networks.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Algebraic Graph Theory

2.2. Neural Network

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. Modeling Assumptions and Motivation

- Application Context: The primary motivation stems from a broad category of real-world applications where drone swarms predominantly operate in planar configurations. A representative example is precision agriculture, where coordinated drone formations are deployed for monitoring vast croplands. In such missions, drones typically maintain a predetermined constant altitude to achieve uniform area coverage, thereby effectively constraining their operational space to an approximately horizontal plane. While minor altitude adjustments may occur, the core coordination tasks—formation maintenance, collision avoidance, and consensus on flight paths—remain fundamentally two-dimensional problems within the plane. Focusing on this plane enables the isolation and rigorous analysis of swarm responses to lateral wind disturbances, which constitute the primary source of trajectory deviations in outdoor environments.

- Methodological Rationale: This reduction from 3D to 2D represents an established and justified methodology in robotics and control theory for initial theoretical development. The 2D model preserves the fundamental challenges of multi-agent consensus, such as nonlinear dynamics and disturbance rejection, while significantly enhancing analytical clarity and reducing computational overhead in simulations [24]. It serves as a critical and necessary first step toward understanding the core principles of the proposed coordination algorithm before undertaking more complex 3D extensions. We explicitly acknowledge that a full 3D model, incorporating turbulent wind fields and vertical dynamics, remains the ultimate objective for real-world deployment. The insights gained from this 2D study will provide a solid foundation for such future work.

3.2. System Dynamics

3.3. Control Object

4. Main Results

4.1. Improved Nonlinear Extended State Observer

- is the estimate of ;

- is the estimate of ;

- is the state estimation error vector;

- , , , , , are tunable parameters;

- and are arbitrarily small positive constants;

- and are nonlinear functions defined by

- (i)

- The disturbance difference is bounded, i.e., there exists a positive constant such that for all k;

- (ii)

- The parameters , , , , , , , and are chosen such that the induced matrix norm (or spectral radius) of satisfieswhere σ is a positive constant,and

- then the estimation error is uniformly ultimately bounded. Moreover, there exists a finite time step K such that for all , the estimation error is bounded by , where the ultimate bound is given by

4.2. Optimal Consensus Control

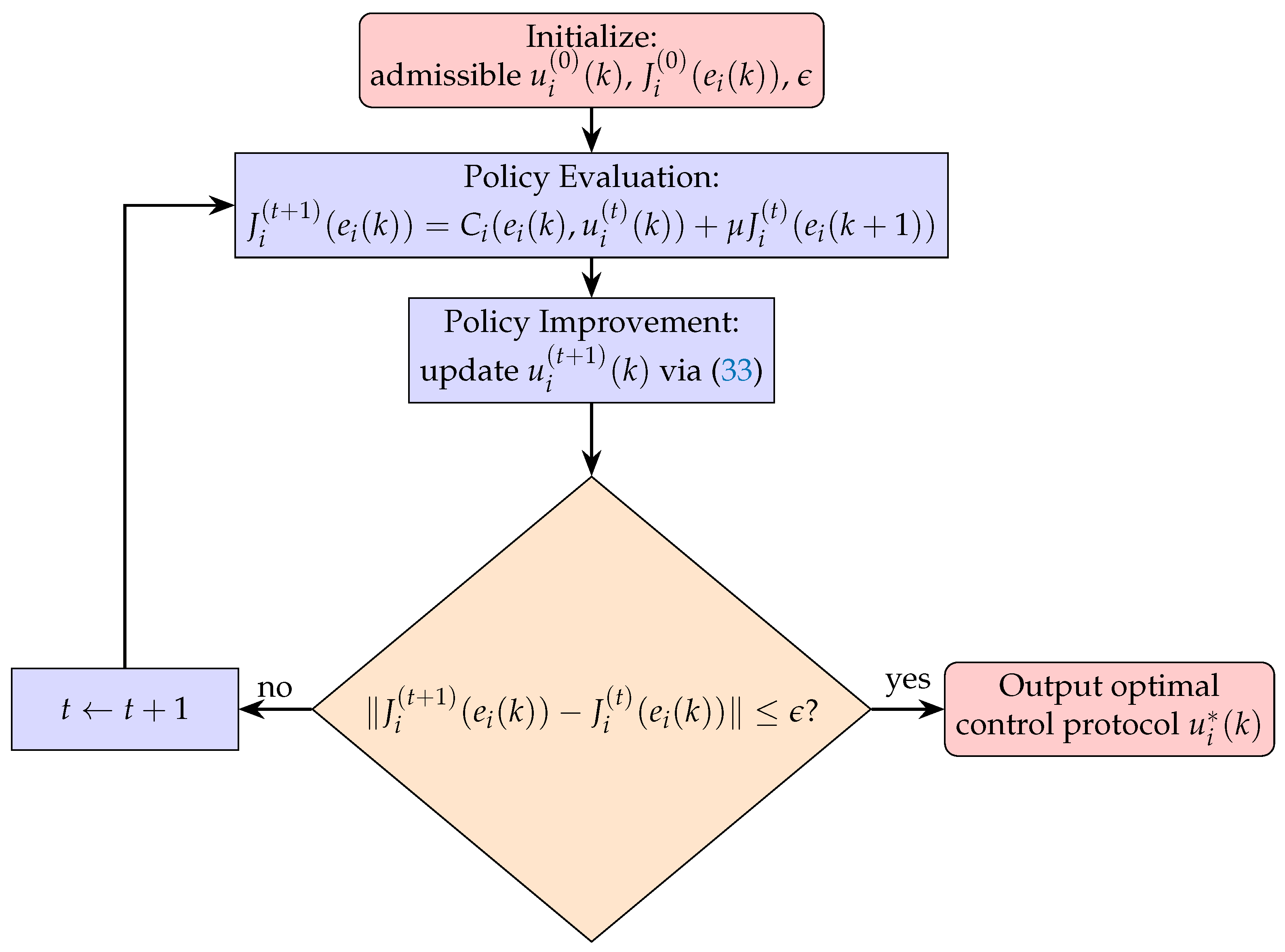

| Algorithm 1 Policy Iteration Algorithm for Optimal Consensus Control |

|

4.3. Momentum-Accelerated Actor–Critic Network

4.4. Opitimal Consensus Analysis

5. Simulation Results

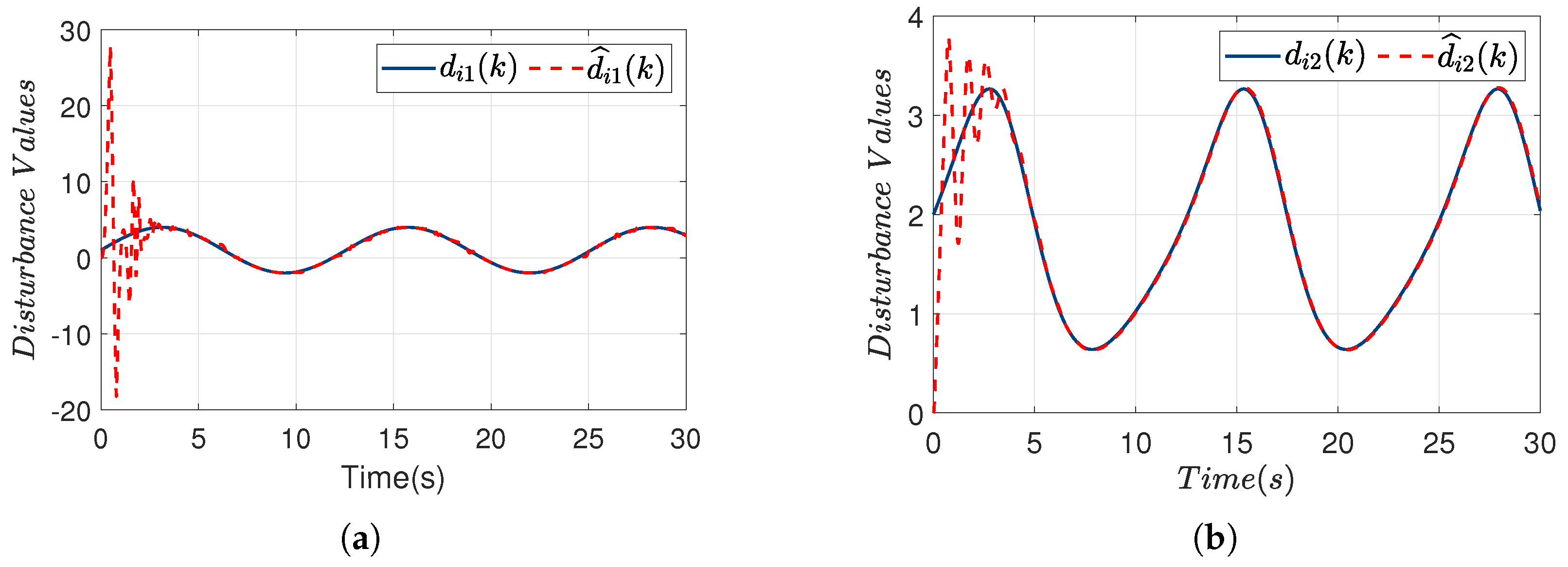

5.1. Simulations for INESO

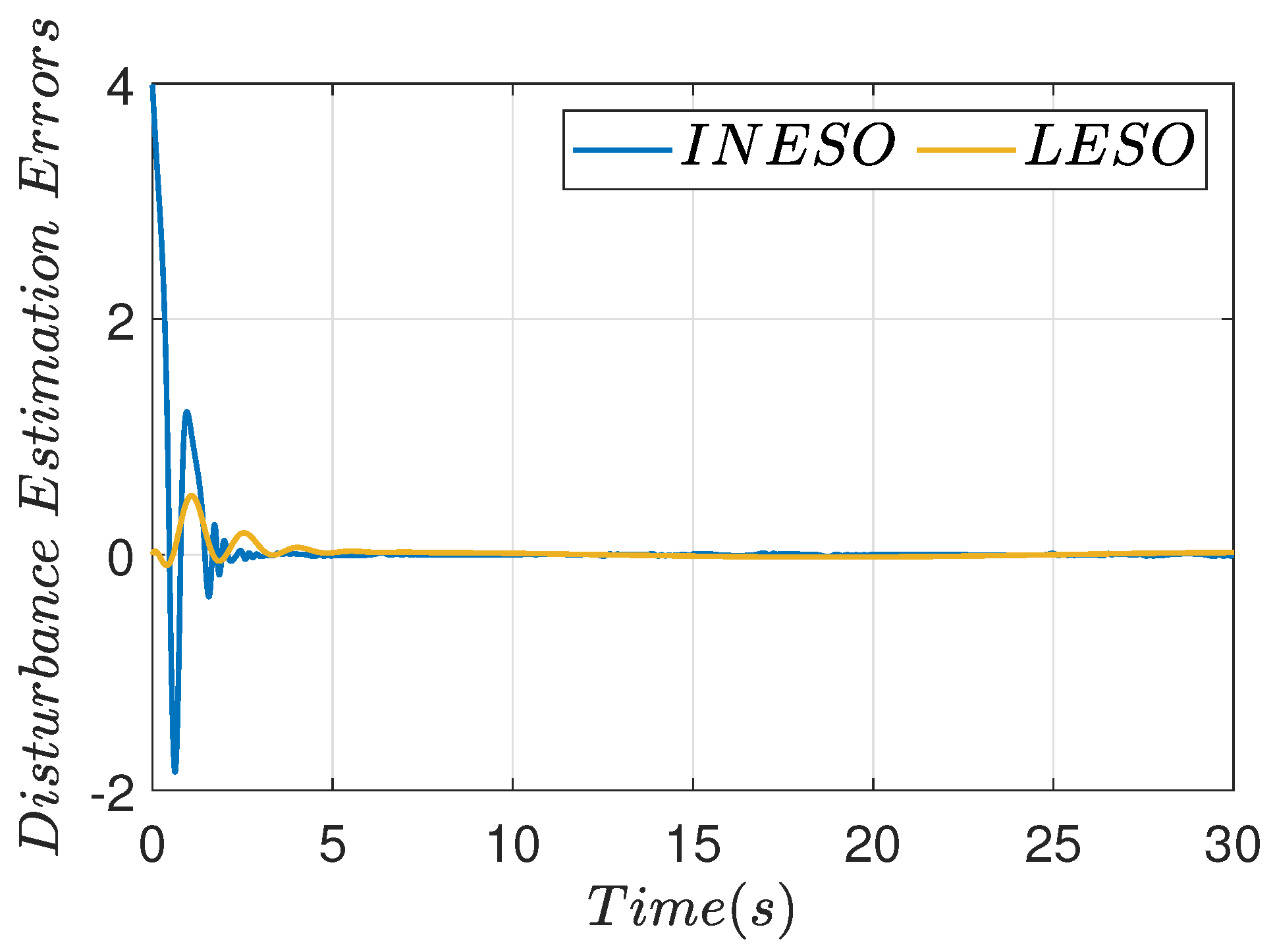

- Enhanced Nonlinear Disturbance Estimation: The nonlinear functions and enable adaptive gain adjustment based on estimation error magnitude. For large errors (), the nonlinear term provides aggressive correction, while for small errors, the linearized term ensures smooth convergence with almost no overshoot.

- Superior Estimation Accuracy: As shown in Table 1, the INESO demonstrates significant improvements over the conventional LESO across multiple key estimation accuracy metrics. The mean squared error is reduced by 46.4%, indicating a substantial decrease in overall estimation bias. The maximum estimation error is reduced by 44.0%, showcasing enhanced robustness against abrupt or large disturbances. Furthermore, the steady-state error is decreased by 48.4%, reflecting the INESO’s ability to achieve more precise disturbance tracking in equilibrium states. This comprehensive enhancement in accuracy directly strengthens the control system’s disturbance rejection and tracking performance, providing a reliable foundation for precise control in high-order, nonlinear, or strongly disturbed environments.

- Faster Convergence Speed: The 42.6% reduction in convergence time (from 4.95 s to 2.84 s) indicates that the INESO achieves stable and accurate disturbance estimates more rapidly. This accelerated convergence enhances the overall responsiveness of the control system, allowing it to compensate for disturbances in a timelier manner, which is crucial for maintaining system stability and convergence performance under dynamic conditions.

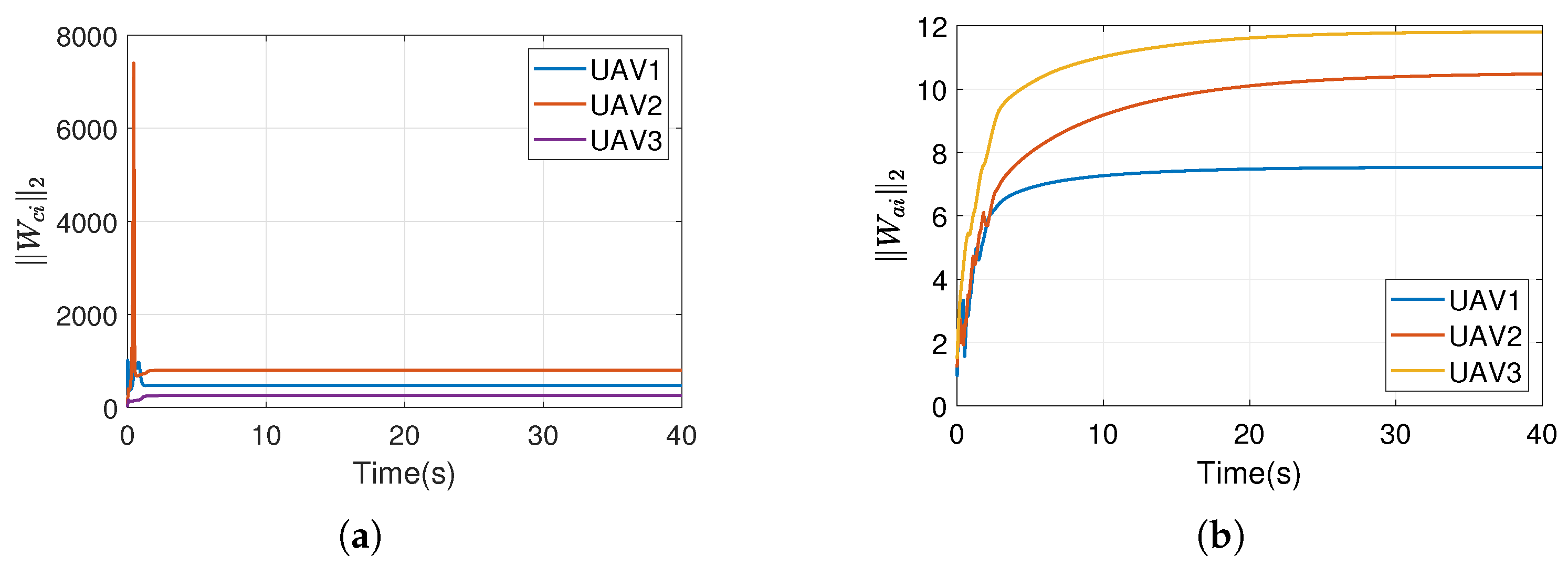

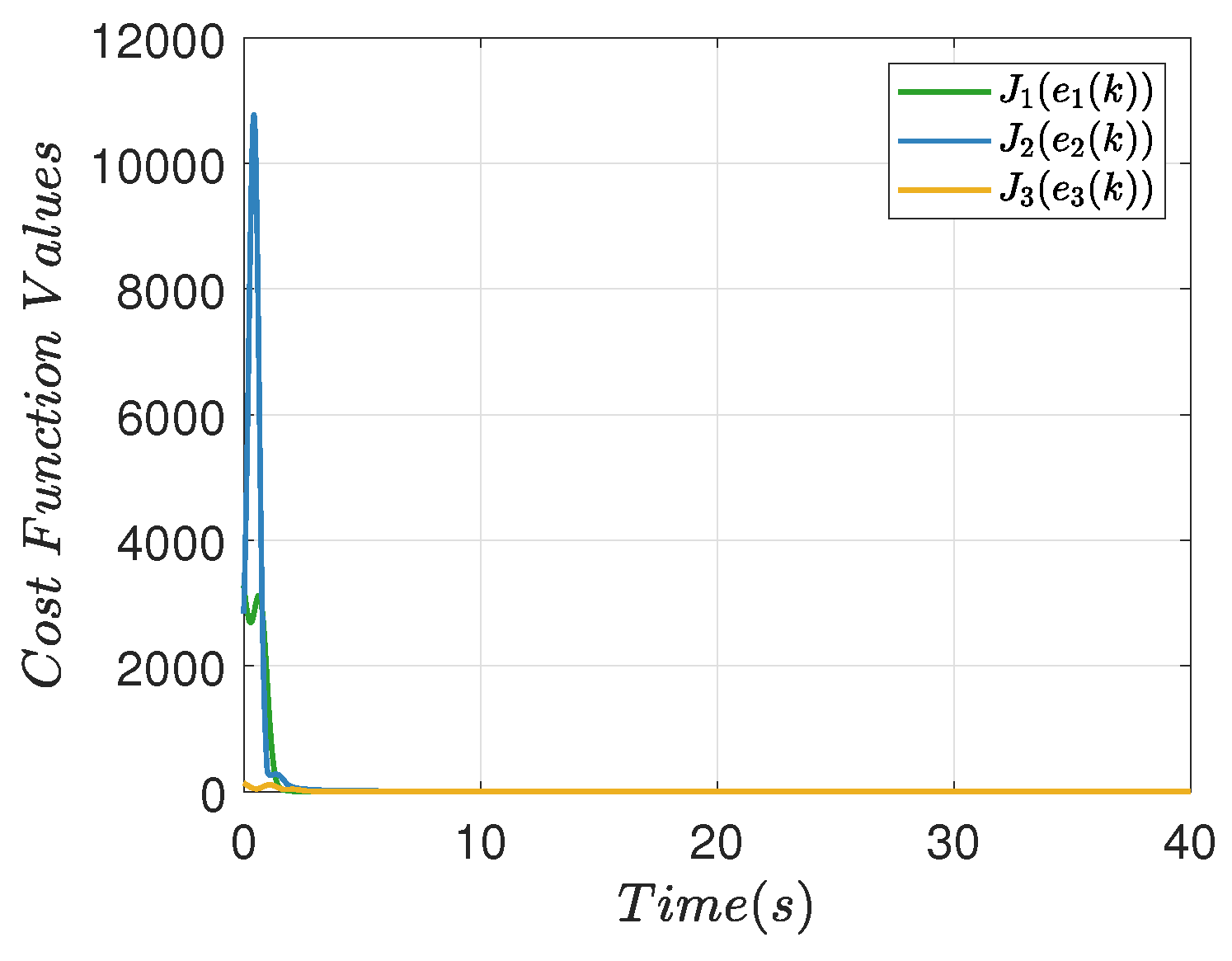

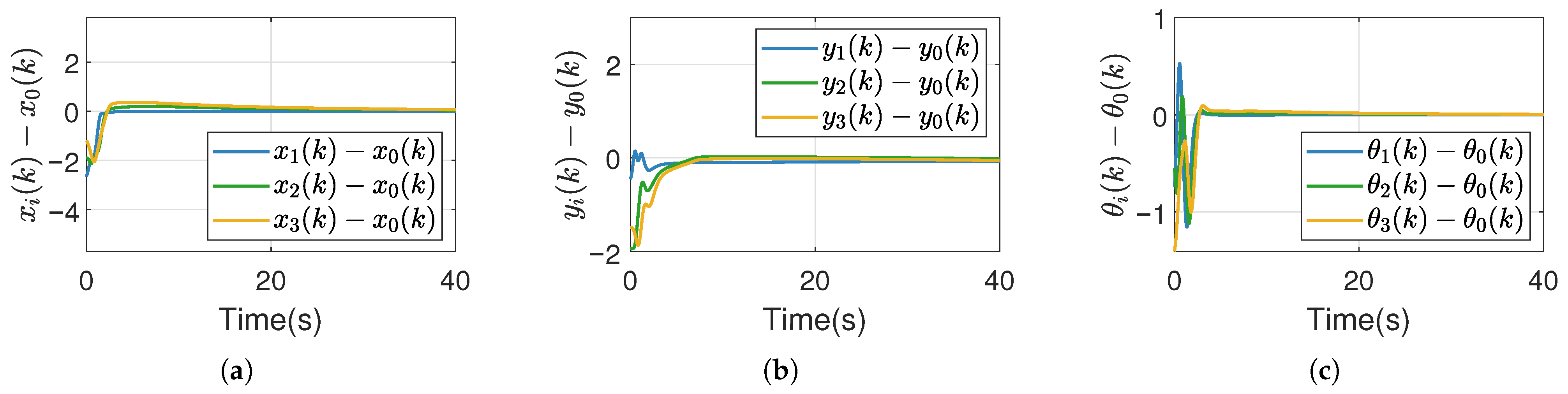

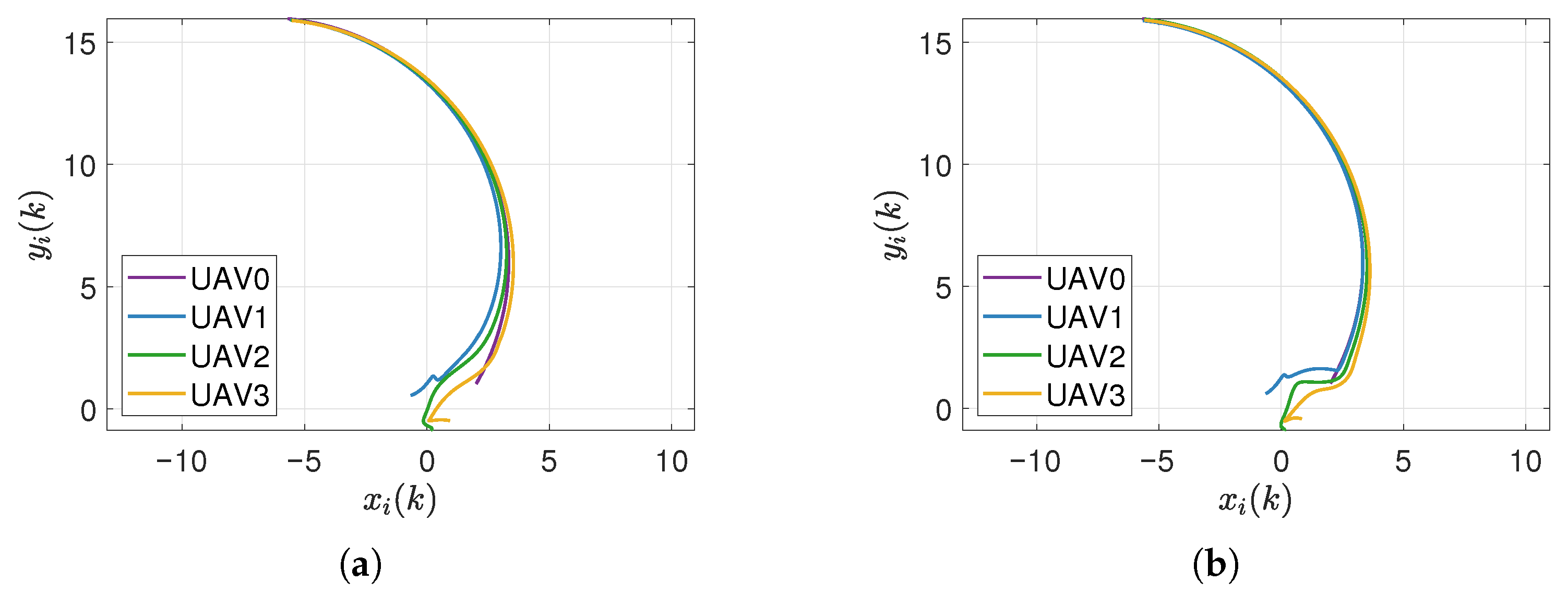

5.2. Simulations for Momentum-Accelerated Actor-Critic Network and Optimal Consensus

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Srikant, R.; Ying, L. 3M-RL: Multi-Resolution, Multi-Agent, Mean-Field Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous UAV Routing. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 8985–8996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logothetis, M.; Karras, G.C.; Alevizos, K.; Verginis, C.K.; Roque, P.; Roditakis, K.; Makris, A.; Garcia, S.; Schillinger, P.; Di Fava, A.; et al. Efficient Cooperation of Heterogeneous Robotic Agents. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2021, 28, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, L.; Wang, X. Active Disturbance Rejection Formation Tracking Control for Uncertain Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems With Switching Topology via Dynamic Event-Triggered Extended State Observer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2023, 70, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.W.; Wang, J. The research on multi-agent system for microgrid control and optimization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, W.; Qin, K.; Li, P. Consensus of Multi-Integral Fractional-Order Multiagent Systems with Nonuniform Time-Delays. Complexity 2018, 2018, 8154230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wang, Y.; Xia, J.; Park, J.H.; Wang, Z. Fault-tolerant leader-following consensus for multi-agent systems subject to semi-Markov switching topologies: An event-triggered control scheme. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 2019, 34, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wen, G.; Wu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, J. Distributed fixed-time consensus for nonlinear heterogeneous multi-agent systems. Automatica 2020, 113, 108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Huang, X.; Yang, B.; Geng, F.; Wang, B.; Hao, M.; Li, S. Formation Tracking Control for Multi-Agent Systems with Collision Avoidance and Connectivity Maintenance. Drones 2022, 6, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qin, K.; Chen, W.; Li, P. Consensus of Delayed Fractional-Order Multiagent Systems Based on State-Derivative Feedback. Complexity 2018, 2018, 8789632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Xie, X.; Qu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Stojanovic, V. Dynamic Event-Triggered Consensus Control for Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Multi-Agent Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 3857–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Hua, C.; You, X.; Guan, X. Distributed Output-Feedback Consensus Control for Nonlinear Multiagent Systems Subject to Unknown Input Delays. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, N.; Qin, K.; Chen, B.; Wu, Y.; Choi, K.S. Distributed optimization for consensus performance of delayed fractional-order double-integrator multi-agent systems. Neurocomputing 2023, 522, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, H.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, G. Data-Driven Optimal Consensus Control for Discrete-Time Multi-Agent Systems With Unknown Dynamics Using Reinforcement Learning Method. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 4091–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, D.W.; Lu, Y.; Deng, C.; Ren, Y. Distributed Fault-Tolerant Bipartite Output Synchronization of Discrete-Time Linear Multiagent Systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 1360–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z. Data-Based Optimal Consensus Control for Multiagent Systems With Policy Gradient Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 3872–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xu, H.; Guan, Z.H.; Ge, Y. Observer-Based Dynamic Event-Triggered Semiglobal Bipartite Consensus of Linear Multi-Agent Systems With Input Saturation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 3139–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qin, K.; Li, P.; Chen, W. Distributed consensus control for double-integrator fractional-order multi-agent systems with nonuniform time-delays. Neurocomputing 2018, 321, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, R.; Zhang, H. Leader-follower optimal coordination tracking control for multi-agent systems with unknown internal states. Neurocomputing 2017, 249, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, T.; Bai, W.; Shan, Q.; Yuan, L.; Wu, Y. Online event-triggered optimal control for multi-agent systems using simplified ADP and experience replay technique. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 106, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Q. Data-Driven Optimal Output Cluster Synchronization Control of Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 3910–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamvoudakis, K.G.; Lewis, F.L. Online actor-critic algorithm to solve the continuous-time infinite horizon optimal control problem. Automatica 2010, 46, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ren, H.; Mu, Y.; Han, J. Optimal Consensus Control Design for Multiagent Systems With Multiple Time Delay Using Adaptive Dynamic Programming. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 12832–12842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Liang, C.; Zhu, Q. Adaptive Fuzzy Event-Triggered Optimized Consensus Control for Delayed Unknown Stochastic Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems Using Simplified ADP. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 11780–11793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhao, L.; Qu, G. Event-Triggered Model Predictive Adaptive Dynamic Programming for Road Intersection Path Planning of Unmanned Ground Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 11228–11243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Fu, W.; Cao, X.; Kou, K.; Tang, J.; Shen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Du, H. A Cooperative Decision-Making and Control Algorithm for UAV Formation Based on Non-Cooperative Game Theory. Drones 2024, 8, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, W.; Luo, B.; Liu, D. A Hybrid Adaptive Dynamic Programming for Optimal Tracking Control of USVs. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 9961–9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liang, H.; Li, H. Event-Triggered Adaptive Tracking Control for Multiagent Systems With Unknown Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Tang, D.; Zhou, T.; Gui, Y. Dynamic job shop scheduling based on deep reinforcement learning for multi-agent manufacturing systems. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2022, 78, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiao, J.; Cheng, H.; Fu, W. Consensus-Based Formation Control for Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems in Complex Environments. Drones 2025, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, H.; Liang, X.; Han, J. Adaptive Trajectory Tracking Control for Double-Pendulum Aerial Transportation System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 9282–9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ho, H.W. Performance-guaranteed quadrotor control with incremental adaptive dynamic programming and disturbance compensation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2026, 163, 113127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wen, G.; Yu, X.; Huang, T. Robust Collision-Avoidance Formation Navigation of Velocity and Input-Constrained Multirobot Systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 1734–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.L.; Guo, B.Z. A Novel Extended State Observer for Output Tracking of MIMO Systems With Mismatched Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2018, 63, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tan, J.; Li, H.; Chen, B. Active Disturbance Rejection Consensus Control of Multi-Agent Systems Based on a Novel NESO. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 30, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.; Li, J.; Xie, L. Reinforcement-Learning-Based Disturbance Rejection Control for Uncertain Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 9621–9633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V.T.; Pham, T.L.; Dao, P.N. Disturbance observer-based H∞ adaptive reinforcement learning for perturbed uncertain surface vessels. ISA Trans. 2022, 130, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, Y.; Li, S. Safety-Critical Disturbance Rejection Control of Nonlinear Systems With Unmatched Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 70, 2722–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; He, H. Continuous-Time Distributed Policy Iteration for Multicontroller Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 2372–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Miao, K.; He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Niu, Y. Fault-Tolerant Time-Varying Formation Trajectory Tracking Control for Multi-Agent Systems with Time Delays and Semi-Markov Switching Topologies. Drones 2024, 8, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Performance Metric | LESO | INESO | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Error | 0.041 | 0.028 | 46.4% |

| Maximum Estimation Error | 0.072 | 0.050 | 44.0% |

| Steady-State Error | 0.046 | 0.031 | 48.4% |

| Convergence Time (s) | 4.95 | 2.84 | 42.6% |

| Average Performance Metric | SGACN | MAACN | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| convergence time (s) | 22.13 | 19.30 | 12.8% |

| Convergence steps | 4426 | 3860 | 12.8% |

| Steady-state position error (m) | 0.075 | 0.058 | 22.7% |

| Steady-state orientation error (rad) | 0.038 | 0.022 | 42.1% |

| Overshoot percentage | 12.3% | 9.5% | 22.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Luo, K.; Li, P.; Pu, M.; Wang, C. Robust Optimal Consensus Control for Multi-Agent Systems with Disturbances. Drones 2026, 10, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020078

Liu J, Luo K, Li P, Pu M, Wang C. Robust Optimal Consensus Control for Multi-Agent Systems with Disturbances. Drones. 2026; 10(2):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020078

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jun, Kuan Luo, Ping Li, Ming Pu, and Changyou Wang. 2026. "Robust Optimal Consensus Control for Multi-Agent Systems with Disturbances" Drones 10, no. 2: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020078

APA StyleLiu, J., Luo, K., Li, P., Pu, M., & Wang, C. (2026). Robust Optimal Consensus Control for Multi-Agent Systems with Disturbances. Drones, 10(2), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones10020078