1. Introduction

Southeast Asia has seen multiple crises in the last decade, all of which have had a substantial impact on state security agendas. In 1997, there was an Asian financial crisis, which was followed by the SARS pandemic in 2003, avian influenza in 2005, Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, the escalation of the Rohingya refugees’ issue in 2017 and, currently, the region is dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. All of these were nonmilitary, yet they were discovered to pose a serious threat to the existence and well-being of the nations and societies [

1]. Indeed, NTS challenges continue to threaten the well-being of nations and communities throughout Asia and the rest of the world. Threat issues are no longer stipulated only the threat of war, but have expanded to include health, food, cyberspace, the economy, smuggling, human trafficking, drugs, and many other issues. Non-traditional security is regarded as a non-military source that endangers the well-being of nations, societies, and communities [

2]. These NTS issues are progressively becoming the highest priority for most governments and policymakers in Asia, as well as in other parts of the world. In summary, the proponents of NTS ought to be extended in terms of security so that those vulnerable, namely non-state actors, political entities, organizations, and human individuals, can have a bigger part in providing or ensuring their security. Transnational issues can cause societal and political instability and, hence, become a threat to society. Thus, it is vital to have multilateral and regional cooperation, as national solutions are not adequate to solve these issues.

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed several security risks to Southeast Asian countries, and has had a devastating impact on their politics, economies, and social stability. As an infectious disease, COVID-19 causes a lot of damage to the sustainable growth of the state. Due to restrictions on people’s movement, other concerns arise, such as regular and irregular migration, which has a spillover effect into neighboring Southeast Asian countries, such as the issue of “Rohingya refugees”. Furthermore, it prompted another issue that posed a threat to people’s health, namely food security challenges, such as food availability, people’s access to food, and adequate food preparation to maintain sanitation and maximum nutrition. Finally, as a result of increased connectivity due to the COVID-19 shutdown and online learning, cyber security issues have increased, resulting in a major increase in cybercrime issues, such as the spread of malware, ransomware, and potential victims of online child sexual exploitation. Therefore, this paper is important as it provides a brief explanation of way of addressing the NTS issues faced by ASEAN due to COVID-19, as well as highlighting the mitigation measures that were implemented to deal with such issues. It will also give guidance to all policymakers, including state and non-state actors, for them to recognize the risk connected with COVID-19 and other NTS risks.

2. Methods

The discussion of this conceptual paper was created using a scoping study of the literature and a secondary data collection approach. In this study, data was gathered using the library research approach. It is based on the findings of previous research on this topic by other researchers. This theoretical research can be used to develop a conceptual framework or hypothesis that reflects the researcher’s overall writings [

3]. Therefore, by utilizing this approach, the researcher would collect significant data on material relating to the researcher’s topic from books, journals, documents, manuscripts, papers, conferences, and online sources, and evaluate it using content analysis. Several keyword search phrases were utilized in this paper, which are “nontraditional security issues”, “COVID-19 in Southeast Asia”, and “mitigation measures by ASEAN”. The literature search was carried out on many websites, including Scopus and ScienceDirect. The initial search yielded 25 (SCOPUS) and 10 (Science Direct) items. However, 20 articles were eliminated owing to their premature conclusions and anecdotes, or because they did not address the NTS concerns during COVID-19 and mitigation measures. Articles that are incomplete, or have a broken connection and overlap were also found during the search. As a result, the final work will be scrutinized until it is reduced to no more than 15 articles, each supported by a variety of publications, hearings, documents, and other reports.

3. Implications of Non-Traditional Security Issues in Southeast Asia during COVID-19

3.1. Infectious Disease (COVID-19)

One of the most serious global non-traditional security risks is the COVID-19 pandemic. This worldwide health crisis has resulted in an unacceptably high number of deaths and a significant economic impact. This year, we have seen that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been evolving into different variants. Even though vaccines are being distributed, the pandemic continues to have a devastating effect on the world. The multiple consequences of COVID-19 have worsened existing socioeconomic inequalities while creating new vulnerabilities and raising the overall degree of risk throughout the world [

4]. In Southeast Asia, as of March 2022, ASEAN member countries have confirmed at least 265,744 reported cases and 3919 death cases. Vietnam has the most daily cases, with around 164,596 cases recorded, while Cambodia has the greatest mortality rate, with approximately 3043 death cases recorded, despite having the lowest incidence of daily cases among ASEAN member nations [

5].

Before the COVID-19 global recession that started in the second half of 2020, Southeast Asia was one of the regions with the highest rates of industrialization and urbanization, as well as one of the regions with the highest rates of population growth. It was one of the first regions to be affected when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus outbreak in the People’s Republic of China. This was due to its close geographic proximity to China, as well as its business, tourism, and supply chain ties to the country. Most ASEAN countries have taken a variety of steps to combat the spread of COVID-19, including forming a special task force on the disease, enacting movement control orders, closing borders, restricting travel, and shutting non-essential businesses, schools, and public spaces [

6].

The ASEAN market is expected to lose US$400 billion (RM1.62 trillion) of GDP growth in 2020 and 2021 because of the pandemic. The dramatic decrease in oil prices, as well as the reduction in exports in several Southeast Asian economies, notably Thailand and Vietnam, has contributed to the economic slowdown. This will have a substantial influence on the business activity of several countries in the area, including the United States. Aside from that, socially disadvantaged groups in ASEAN countries, particularly those in the informal sector, have been adversely affected by COVID-19, as well as by the containment measures taken by governments. They did not have enough access to healthcare, and many had constrained living environments that increased their chances of being exposed to the disease. However, the community quarantine also places them in a more vulnerable situation with no income, loss of job, no savings to restock goods for families, and no access to the social safety net.

3.2. Regular and Irregular Migration

The effects of COVID-19 have impacted almost all migrants, whether they are migrating domestically or internationally, forcibly or voluntarily, and on a regular or irregular basis [

7]. It caused further difficulties for migrants, particularly those who were illegal. Regular migration can become irregular due to changes in national laws and policies, and vice versa. Since the deployment of strengthened border controls and limits on the freedom of movement around the region due to COVID-19, there has been an increase in countries refusing entry to abandoned ships carrying Rohingya migrants, prompting worries of a repeat of the 2015 “boat people crisis”. Because there was no coordinated response to the crisis at the time, most of the countries involved agreed to the 2016 Bali Declaration, which outlined action to avoid its repetition. Even though at a recent meeting of the Bali Process Task Force on Planning and Preparedness, countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, stressed the importance of “saving lives at sea and not putting people’s lives and safety at risk when responding to irregular maritime migration”, this seems to have not been maintained in the face of COVID-19. Malaysia has previously allowed boats, although, on an ad hoc basis, and its position has hardened in recent months [

8].

Many Rohingya Muslims have fled Myanmar and are now living in overcrowded refugee camps in Bangladesh, with some being trafficked throughout Southeast Asia. They have a far higher risk of infections of the coronavirus because they lack basic healthcare and precautions [

9]. It is estimated that the majority of the seven million migrant workers in and from ASEAN are undocumented. As undocumented workers, they are not entitled to any form of social protection. Apart from the risk to their health, this also jeopardizes the host country’s restricting measures. After losing their employment in Thailand owing to travel restrictions enforced from March to May, about 150,000 migrant workers from Myanmar, 50,000 from Cambodia, and 60,000 from Laos went home. Indeed, COVID-19’s impact on the labor market left many of them trapped and with terrible employment prospects. Due to this, the number of people living in poverty and hardship will increase [

10].

Furthermore, the pandemic also put them at risk due to uneven refugee protections across Southeast Asia countries. Only a few states have ratified the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, and the rest have not agreed-upon principles or standards for protection within ASEAN. This allows the countries to react in whichever manner they see fit. So far only Cambodia, the Philippines, and Timor-Leste in Southeast Asia have agreed to sign the United Nations’ 1951 Convention on Refugees and the 1967 Protocol on Refugees’ Status [

11]. The UNHCR Director for Asia and the Pacific has criticized the Bali Process, claiming that there is no concerted reaction from ASEAN member nations, and that worries of COVID-19 are being exploited to send boats out to sea. As a result of this issue, at least 30 refugees died during the journey after being stranded on the sea for about seven months.

3.3. Food Security

There are around 61 million people in Southeast Asia who are malnourished, and this number may continue to rise as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak [

12]. Indeed, COVID-19 has exacerbated food security issues in some parts of the world, particularly in the Asia–Pacific region, where stringent quarantine regulations and export prohibitions on essential foods have affected every stage of the food supply chain [

13]. The logistics of the food value chain, including transportation, warehousing, procurement, packaging, and inventory management, have been affected, which has an effect not only on the amount of food that is available but also on its quality, freshness, safety, market access, and cost. As a result, it leads to an increase in hunger and the number of malnourished children under five that suffer from poor growth and development globally due to COVID-19. Indonesia is one of the countries hardest hit by the COVID-19 virus in Southeast Asia. Overburdened healthcare facilities, disrupted food-supply networks, and income loss as a result of the pandemic might all contribute to a significant increase in the number of malnourished children in the archipelago. Similar to Cambodia, the rate of poverty remains high, and there is lack of food supply, and rise in the prices of food due to the crisis. Singapore also faces major challenges in the food supply chain, including food imports, local manufacturing, retail grocery shops, food and beverage services, and in terms of vulnerable people’s care [

14].

The pandemic poses a threat to food security in terms of the production and availability of food, physical and market access, and impact from imported products. Due to lockdown, all farmers are unable to get agricultural products required for the cropping process, such as fertilizer, seeds, and pesticides. If there is not enough fertilizer, agricultural output will decrease. If there are not enough seed and pesticides, crops will be more sensitive to natural stresses, such as droughts and floods, as well as pests and diseases. Thailand and Vietnam were affected by this problem, since they are among Asia’s top rice exporters. The prices of food will also be increased when physical access is restricted and food is scarce. When this happens, it affects poor people the most. The poorest households were unable to purchase enough nutritious food as prices increased, and most of them reduced their food intake to save more money. In Malaysia, 63.76% of respondents from the Bottom 40% (B40) families have reduced their food intake to save more money [

15]. As in Vietnam and Laos, individuals with low incomes were forced to eat less nutritious meals owing to increased food costs.

3.4. Cyber Security

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the pace of digital transformation, compelling both the public and private sectors to embrace it, transforming the work, study, retail, and business environments. Digital transformation has also opened up new opportunities for cybercriminals to attack the computer networks and systems of people, companies, and even multinational corporations [

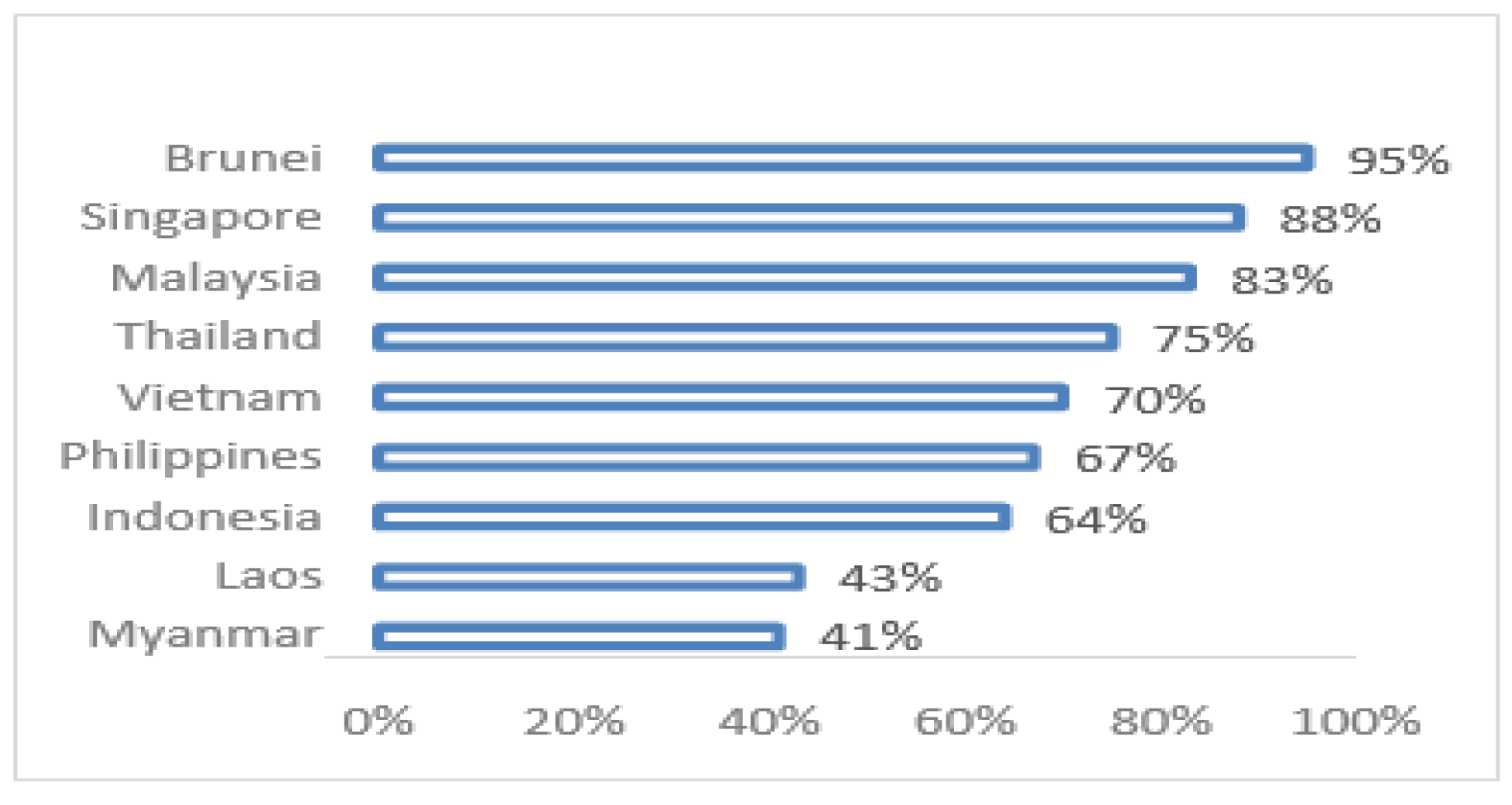

16]. As refer to the

Figure 1 below, it shows that Southeast Asia has a 66% Internet penetration rate. On the higher end of the spectrum, Brunei has a 95% of Internet penetration rate followed by 88% in Singapore, 83% in Malaysia, 75% in Thailand, 70% in Vietnam, 67% in the Philippines, and 64% in Indonesia. At the lower end of the spectrum, in Laos and Myanmar, the penetration rate is 43% and 41%, respectively.

Thus, as people become more reliant on the Internet, a multitude of new security threats have emerged, all of which have the potential to cause significant harm. As a consequence, digital economic trust and resilience will be diminished, preventing the region from achieving its full digital potential if no action is taken to make it secure. Malicious emails, fraud, phishing attacks, and malware have all escalated in the last 18 months as a result of the pandemic. Small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) have become popular targets for cybercriminals, with many being hacked or losing data. Most of these companies are unaware of how to protect their data from cyberattacks. Small and medium-sized enterprises in the region should prioritize cyber security in light of recent cyberattacks on the systems of several ASEAN nations, including Indonesia and Malaysia [

18].

Furthermore, as Internet access and mobile device penetration have increased during the COVID-19 lockdown, children have spent more time online than ever before in recent years. Due to this, there has been a significant increase in the number of potential victims of online child sexual exploitation. It also stated that COVID-19 has resulted in a major surge in child exploitation in many parts of the world. Lockdowns are driving children from low socioeconomic situations to engage in Internet prostitution due to financial concerns. It is also becoming increasingly difficult for these children to receive adequate supervision because of limited access to childcare and other support services.

4. Asean Mitigation Strategies towards Selected Non-Traditional Security Issues during Pandemic COVID-19

4.1. The COVID-19 Pandemic

Southeast Asia has proved that regional cooperation which is through ASEAN is essential for assisting the AMSs to mitigate the COVID pandemic without working at the global level. Several efforts and initiatives were introduced and implemented by ASEAN in order to deal with this public health crisis. It can be seen that, on 10 March 2020 in Da Nang, Vietnam, the 26th ASEAN Economic Ministers (AEM) conference purposely stressed the importance to have a coordinated effort to strengthen the economy in response to the outbreak of COVID-19. It also emphasized the use of technology, especially in economic activity, such as e-commerce and trade facilitation in the digital economy platforms, such as the ASEAN Single Window, which assists the SMEs to continue operating during COVID-19. These SMEs were being given an opportunity to upgrade and enhance their supply chain connectivity, as well as allow them to operate the business as usual [

5].

Furthermore, instead of having regional cooperation, ASEAN is also collaborating with its Development and Dialogue Partners. This started in March 2020, whereby ASEAN and the EU collaborated through a Ministerial Video Conference to discuss several challenges in mitigating the COVID-19. The important outcome of the meeting was that ASEAN needs to invest more in scientific research and maintain the supply chain so that it will be able to minimize the negative impact of COVID, particularly in the economy and social sector. Besides this, ASEAN continues to work with another dialogue partner, the US. In April 2020, the two powers purposely discussed improving a public health cooperation in a more progressive manner. Furthermore, ASEAN also continues to work together with the ASEAN Plus Three (South Korea, Japan, China) through video conferencing by sharing and learning from South Korea how to best manage the pandemic, because of the successful effort carried out by South Korea to flatten the curve without imposing movement restrictions or an economically damaging lockdown. Additionally, the establishment of the ASEAN Respond Fund also was discussed during the Special ASEAN Summit in order to ensure every proposal of the meeting could be implemented, and that the goal to mitigate the pandemic could be easily achieved.

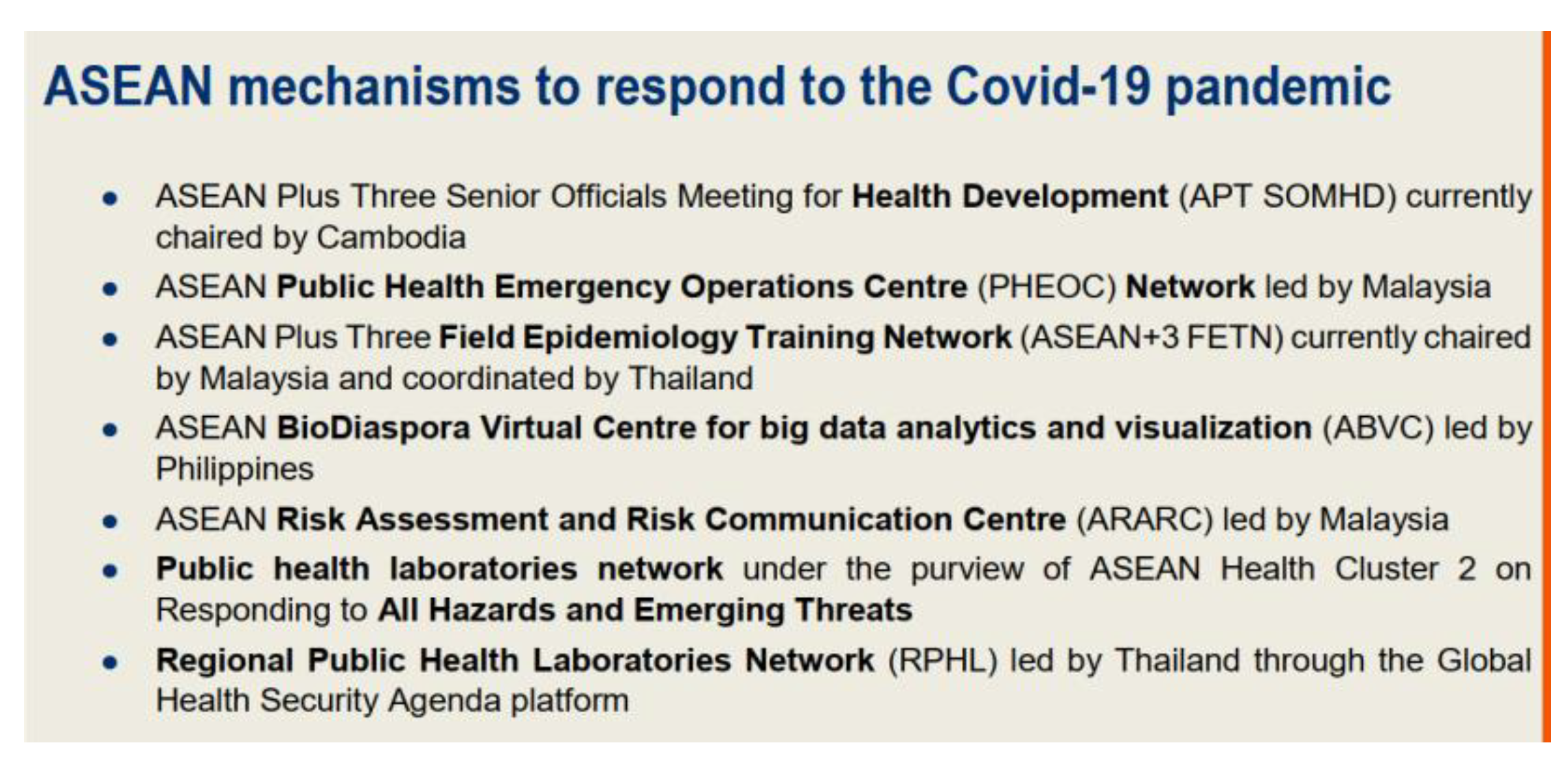

Additionally,

Figure 2 below show that ASEAN has also created several important apparatuses to combat this pandemic, such as the ASEAN Emergency Operating Centre Network for Public Health Emergency, and the ASEAN BioDiaspora Virtual Centre. These two important mechanisms were established in order to facilitate and provide accurate information and technical inputs related to this disease. It is also responsible for initiating health protocols, such as quarantine measures, testing techniques, tracing close contacts, and isolation that must be followed by AMSs. Apart from that, ASEAN also strives to combat false news and misinformation about COVID-19 issues by establishing an ASEAN Risk Assessment and Risk Communication Centre. They will help to provide a control measure and disseminate relevant prevention actions in such matters. The ASEAN also has created a Regional Public Health Laboratories Network purposely to give support and expertise, especially on scientific research and technical support among AMSs.

4.2. The Regular and Irregular Migration during COVID-19

The ASEAN has also addressed several best approach and initiatives, especially among employees, and particularly in regard to the migrant workers that were badly affected due to the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the measures taken is to provide free COVID-19 testing and healthcare to the migrant workers in order to deal with the process of automatic visa extension. Furthermore, the process of registration, management of logistics for organizing returns, providing support and temporary income support for returnee migrants have also been implemented. Additionally, efforts have been made at the national level, whereby most AMSs, such as Philippines and Thailand, provided the affected migrant workers with a one-off cash transfer and assisted their return home through chartered flights. In addition, Thailand as a receiving country also gave support to migrant workers by granting permission to stay and work to those from Myanmar and Cambodia. Not only that, but depending on their contributions and terms of service, they were also eligible for unemployment insurance and severance money. Furthermore, Singapore also provides migrant workers with counseling and covers the cost of COVID-19 testing and treatment, whilst Malaysia offers migrant employees COVID-19 screening subsidies.

4.3. Food Security Issues during COVID-19

The ASEAN has developed a number of initiatives and measures to ensure food security in Southeast Asia as a result of COVID-19. It began on 15 April 2020, when ASEAN published a joint statement during the ASEAN Ministers of Agriculture and Forestry (AMAF) meeting, aimed at strengthening the ASEAN countries’ commitment to ensure food security, food safety and food nutrition during pandemic. It focused on minimizing the disruption of food supply chains, ensuring the markets remained open, and facilitating the shipping process for agriculture and food product. Additionally, ASEAN also seeks to provide a sustainable supply of adequate, safe, and nutritious food that fits the dietary requirements of ASEAN communities during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The ASEAN social protection programs also was expanded, especially to the smallholder farmers of micro, small, and medium enterprises inorder to assure countries food security and promoting food production [

19].

Due to the high level of food self production and the active supply chain among the AMSs, Intra-ASEAN commerce also were vitalized by ASEAN, especially in terms of food activity, such as transmitting the raw materials from producer to the processor and towards the end to the consumer. It essentially took critical steps to preserve various activities, such as harvesting and delivering food by ensuring labor availability and establishing agri-food as a critical service [

20]. Additionally, ASEAN is currently operating on a new set of digital agriculture rules and procedures as digitalization becomes important due to the post COVID-19 era. It is also known as knowledge-driven agriculture, which is focused on improving labor and land productivity. The use of the Internet and technology has increased due to COVID-19 and, therefore, it is urged that ASEAN countries move into digitalization of their agriculture sectors.

For instance, ASEAN has implemented a Green Revolution Technologies purposely to enhance crop varieties by using a conventional breeding methods. Other than that, Smart Farming also was introduced in order to assist and support the farmer through the use of laser guided tractors, GPS and also ploughing equipment. FINTECH, on the other hand, was made available to all small farmers in various ASEAN countries via credit and loan services, allowing them to trade in both local and national markets [

21].

4.4. Cyber Security Issues during COVID-19

Throughout COVID-19 in Southeast Asia, ASEAN made numerous efforts to address cyber security concerns. To begin, a special webinar was held to raise public awareness about cyber security risks. The ASEAN Foundation, with the support of Microsoft, launched the ASEAN Cybersecurity Skilling Programme (ASEANCSP) during the “Cybersecurity in ASEAN: Lessons for Youth and How the COVID-19 is Shaping the Every-Evolving Digital Landscape” on 24 February 2022 [

22]. The ASEANCSP was designed to help people in ASEAN have a better understanding of cyber security. These master trainers will then impart cyber security knowledge to 30,000 underserved young people across ASEAN member countries. This will contribute to the development of a secure digital ecosystem in the region. In addition, The ASEAN–Singapore Cybersecurity Centre of Excellence (ASCCE) also aims to improve the creation, legislation, and research capacities of member states’ cyber security strategies. It is critical to address cyber security challenges in ASEAN countries through technical training, information sharing on cyber risks and attacks, and best practices across these teams. A cyber think tank is also part of the center’s job. It carries out research and training in several areas, such as international law, cyber strategy, cyber law, cyber norms, and other cyber security policy issues [

23].

In order to ensure that children received a significant benefit from online opportunities, ASEAN Member States have realized that there is an urgent need for collective action, as well as to improve laws at national and regional levels. One of the collaborations that have been made between ASEAN and UNICEF is through the Safe Online Initiative. This program explicitly promotes internet safety through better legislation and provides support and guidance, investment, and also the building of partnerships at the regional and national levels. The ASEAN region also has committed over US$ 10 million to it. Other than that, ASEAN has also developed a regional plan of action, the ASEAN-ICT Forum, to occur every year in order to assist private sector companies, especially financial institutions, Internet services providers, and social media by working together to keep children safe online. It is crucial and shows a timely commitment by the AMS to ensure that children and young people can use the Internet safely without being exploited and abused.

5. Discussion

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has made numerous efforts to mitigate the resulting non-traditional security issues. It is a global health problem that should be best addressed through a coordinated regional response. A regional reaction is more essential than ever to support national measures. The COVID-19 Vaccine for All that was implemented by ASEAN is one of the initiatives under the ASEAN socio-cultural community pillar that should be one of the significant security improvements in combating the threat of COVID-19. It can be shown by the declaration of endemic status in several AMSs, such as Brunei on 15 December 2021, Malaysia in April 2022, and Thailand by July 2022. The number of positive and death cases also reduced, as the new variant, Omicron, is 75% less likely to lead to the development of serious illness or death than in those infected with the Delta variant. As a result, the political and economic issues can be slowly resolved and mitigated once the virus has been thwarted.

Moreover, it is recommended that the migrant workers should receive social protection in proportion to their economic contributions to their country. Additionally, such a system should strengthen cross-border social protection for a highly mobile population. If they are unable to return to their home country, they should be allowed to obtain emergency social assistance in the country they are being sent to. This will help not only the migrant workers’ health and economic well-being, but also the host country. Aside from that, the government must take aggressive steps to address people’s most fundamental need, which is food, by giving financial help and support to keep small farmers competitive in production while ensuring that impoverished customers receive appropriate food. The government may utilize a variety of measures, including subsidies, financial support, price regulation, and import licenses.

On the other hand, it is important for AMSs to take immediate collective action and enhance legislation at the national and regional levels in order to prevent and respond to online exploitation and abuse while ensuring that children have no barriers to participating in online opportunities. The ASEAN also should continue to strengthen existing cooperation and identify existing gaps to improve and enhance the regional cyber security agenda. This cooperation will further strengthen ties between AMSs and provide a more general understanding of how to deal with cyber-attacks targeted at the Southeast Asian region.

As a result, during COVID-19, non-traditional security concerns cannot be dismissed as a minor matter, but rather must be viewed as serious security risks. Government must pay attention to socioeconomic shifts and broaden their awareness of security risks beyond the military. More importantly, it must also be recognised that many of these problems, such as pandemics and the environment, affect more than one country. This means that states cannot solve these problems on their own. To deal with these security threats, it is important for states and non-state actors, such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), to work together on a regional level. Only by pooling their resources, knowledge, and skills will these players be able to effectively handle the ever-increasing complexity of non-traditional security. Thus, ASEAN’s unity is essential to overcome challenges due to the global financial crisis, climate change, natural disasters and, now, the COVID-19 pandemic.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the emergence of COVID-19 has resulted in major disruptions to the AMSs, most notably to the economy, as well as to the social and political stability of the states. This may be seen through the quarantine or lockdown measures that have been enforced by AMS, which have contributed to an economic slowdown because they decrease export activity and reduce the supply of food. A limited food supply will indirectly contribute to growing hunger, particularly among children with stunted growth and those from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Loss of jobs, lack of resources, and lack of access to a social safety net all contribute to an increase in poverty. Furthermore, cybercriminal assaults targeting SMEs in Southeast Asia will detract from ASEAN’s goals to adopt a Go Digital ASEAN policy as part of digital economy activities.

In addition, it is essential for the AMSs to address the requirements and to take immediate policy action in order to deal with all of the NTS dangers that have arisen as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to effectively combat the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to give it not just more serious attention at the national level but also at the regional and global levels. This is because the pandemic has an influence that cuts across multiple levels. Furthermore, strong support and a response from every AMS to mitigate the NTS issues are needed to ensure that all the programs, policies, joint action, and other initiatives can be successfully implemented, as well as to achieve their intended goals.