1. Introduction

Domestic violence is a global issue that occurs throughout the world. It is not isolated to Malaysia and is a widespread phenomenon among countries such as Pakistan, China, India, Brazil, and Japan. It was reported that in Dhaka, 60% of the housewives have been battered by their husbands [

1]. Grossman and Lundy (2007) stated that domestic violence occurs across all ethnicities and racial groups, profoundly affecting women, who are most frequently the victims. Women were abused in various forms, either physically, socially, financially, sexually, psychologically, or emotionally, and contends that female victims of violence should be given special attention and comprehensive assistance. It is pointed out in [

2] that in America, approximately, 4 million women are battered each year, with injuries caused by their husbands or partners. Up to 50 percent of homeless women and children are fleeing domestic violence. Malaysian survivors’ need for shelter demands urgent attention, as domestic violence shelters are sorely lacking in Malaysia. International best practices recommend a minimum of one family place in a women’s shelter per 10,000 people, but Malaysia only has an estimated one family place per 72,538 people. It is reported in [

3] that shelter availability in the Klang Valley found that, even while the numbers of government domestic violence shelters are inadequate, they are simultaneously not being fully utilised by women in need. In contrast, NGO shelters were found to be consistently at or over capacity [

4].

Women are the primary focus of domestic violence studies. It is stated in [

5] that domestic violence is prevalent not only in all races but across all occupational and age groups as well, and that across all these ethnographic and demographic groupings, domestic violence profoundly affects women, who are the most frequent victims. Women are abused in various forms, either physically, socially, financially, sexually, psychologically, or emotionally. Ref. [

6] argues that women who have been subjected to violence should be able to access assistance, and their cases should be given special attention. Following this, the government allocated RM21 million towards domestic violence support centres in Budget 2021. Other recommendations were also included in Budget 2021, including increased government social workers through the MySTEP program and financial support for childcare.

2. How Bad Is Domestic Violence in Malaysia?

In Ref. [

2], domestic violence is defined as when a partner is treated violently, including physical, sexual, psychological, and social abuse. Domestic violence behaviour includes: (i) deliberately subjecting the victim to fear; (ii) subjecting them to physical injury; (iii) coercing their behaviour; (iv) threatening and/or committing sexual acts; (v) confining or detaining the partner involuntarily; (vi) treachery; or (vii) damaging property with the intent of causing grief or annoyance. (Domestic Violence Act 1994, s. 2;. In many cases, domestic violence is only revealed to others after the victim becomes severely injured or is even murdered by their abuser. Abuser identities are not restricted to partners, they can also be a grandparent(s), parent(s), child(ren), or a disabled family member. The diversity of victims is equally inclusive. The UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women (UNTF EVAW) surveyed 122 of its grantees from 69 countries worldwide. They found that key factors exacerbating violence included food shortage, lockdowns, unemployment, and economic insecurity [

7].

In Malaysia, ref. [

8] highlights that before the enforcement of the Domestic Violence Act (1994), the number of domestic violence cases between 1991 to 1994 was less than 300 cases per year. However, according to the Royal Malaysian Police Force, it was reported that based on the statistics of violence against women in Malaysia from the years 2000–2006, the number of reported cases was more than 2500 per year [

9]. This demonstrates that the number of domestic violence incidents remained very high, even after the enforcement of the Act in 1996. The former minister for Women, Family and Community Development, Datuk Seri Shahrizat Abdul Jalil, expressed her view that violence against women has increased alarmingly, despite the measures taken to tackle it [

10]. She noted that despite the enforcement of the Act, there were still 3264 cases reported in 2006. She further stated that the statistics showed a worrying trend of rising cases of domestic violence. Considering that this issue has been extensively debated, and continues to be through electronic and print media, and contentious differences of opinion remain between certain quarters, researchers are prompted to propose research questioning how far the Domestic Violence Act (1994) has gone in providing protection for women.

Previously, compilations of research on social problems have raised the issue of domestic violence in Malaysia, dating back to the 1970s, including a book produced by university academicians titled “Transformasi Masyarakat: Cabaran Keluarga, Gender dan Sosiobudaya”, which began to get scholarly attention by the mid-2000s. Later, ref. [

11] found that domestic violence—either to children, spouses, elderly relatives, or disabled people, had become a new social problem that had shown an increased number of cases and had otherwise worsened in severity, and thus this phenomenon needed to be tackled throughout Malaysian society [

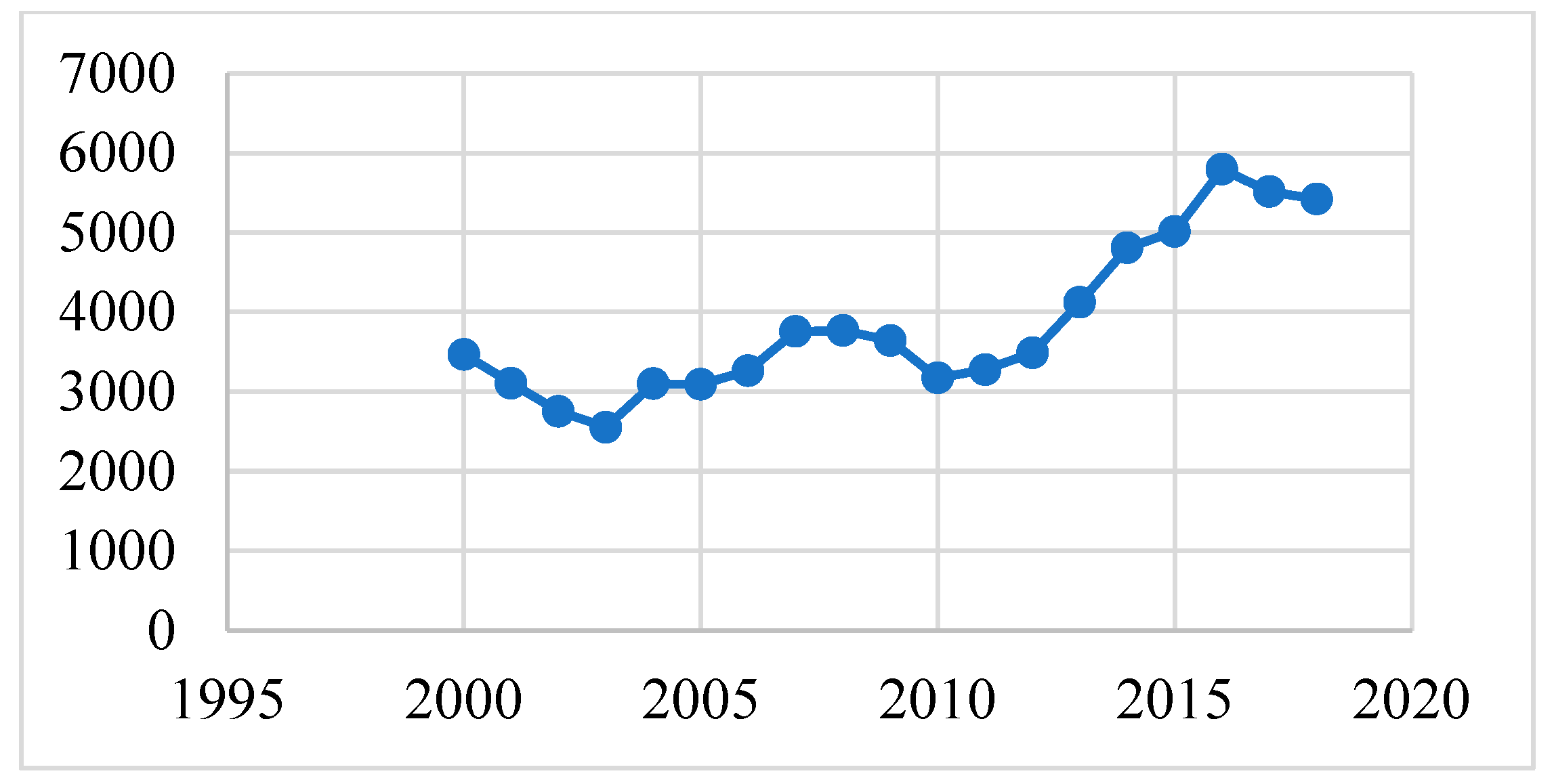

12]. Statistics show an alarming trend of yearly increments in domestic violence cases in Malaysia—as reported by the Ministry of Women, Family and Society Development and the Malaysian Royal Police (PDRM) (see

Figure 1 and

Table 1 below).

Since the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia, that started with first case on 25 January 2020, the Malaysian government imposed a Movement Control Order (MCO), to curtail the spread of the deadly virus. Malaysian citizens were forced to stay at home during this time, and this new scenario situated domestic violence victims under the same roof as their abusers, with only limited avenues of escape from these abusive actions. unsurprisingly, during the first MCO (2 October 2019–17 March 2020), the Malaysia Royal Police recorded 3258 domestic violence cases—a significant increase. During the MCO from 18 March 2020–31 October 2020, a further 3080 cases were recorded. The rate of cases of domestic violence reduced slightly after the government loosened the MCO restrictions during the recovery stage of the pandemic. Further waves of the pandemic spread again, with some localised MCOs extending into 2021, and the domestic violence issues remained.

Various police reports detail prolonged domestic violence that resulted in the murder of the victims [

13]. Recently, the nation was shaken again after a boy was badly abused and brutally murdered under the care of his mother and stepfather, only three months after he was taken from his adopted family. Based on reports, there are many evident reasons why domestic violence increases during the MCOs, including:

Abusers were always with the victim, spending more time together, increasing the chance of proximal conflict;

Social isolation reduces opportunities for other outlets to channel or relieve stress;

Financial problems and future uncertainties significantly increased conflicts and stress;

A narrow or unconducive home environment causes drowning when at home;

Abusers with drug addiction habits had difficulty obtaining supplies, both due to movement restrictions, and financial factors;

Victims were unable to run away from the domestic violence situation due to movement restrictions;

Absence of support from others, and no place to seek support, as many services had to close during MCO;

Victim dependence on the abuser may have increased, as a result of restrictions, which exacerbates this abusive potential.

In summary, it was not the MCO that led to increased quarrels or abuse directly, but rather that domestic violence that was already happening before the MCO was now made worse when victims were unable to flee from their attackers.

3. Sufficiency of Initiatives and Law to Protect Domestic Violence Victims

In order to protect domestic violence victims, the Malaysian National Security Council (MKN) provided a helpline, Talian Kasih, together with the WAO helpline, to assist victims (beginning from the first MCO) [

14]. Women’s Aid Organisation reported that the helpline received 3.4 times as many calls related to domestic violence since the beginning of MCO in May 2019—highlighting the desperate need for more initiatives to support victims. MCOs were targeted to control the spread of the COVID-19 virus to keep the public safe, however in hindsight, the government should have taken into account that staying home was definitely not a safe place for women, children, the elderly, or those with disabilities, who are subject to abuse from family members. Furthermore, the MCOs limited the operations of shelters to receive domestic violence victims during the MCOs, and this situation trapped victims with their abusers, who controlled them physically, emotionally and socially.

In cases of domestic violence, first and foremost, the rules and regulations must be sufficient to protect the victims and bring abusers to justice. Currently, the Domestic [

15] is enforced throughout Malaysia due to the increasing rates of domestic violence crime. The government believes that if it is not curtailed, it will result in a deterioration of the moral and social fabric of Malaysian society. The Domestic Violence Act (1994) is a law that pays special attention to domestic violence cases by providing several solutions for such cases [

16]. Women’s organisations in Malaysia faced nearly a decade of struggle fighting to protect domestic violence victims before the Domestic Violence Act was passed in 1994, under this law, domestic violence was legally declared a crime.

According to the act, where domestic violence occurs, third parties can report information to public welfare officers or police officers, in order to take action under the authority as enforcement officers. Those parties include the spouse, ex-spouse, daughter or son, mother or father, brother, sister, or any family members, as well as the lawyers of the victim. If the victim is a minor, or disabled adult, the caretaker or any person responsible for the child or disabled person can also report. The application to get a protection order can be made at the victim’s residence, the residence where a victim is brought to live, a residence where the domestic violence has occurred, or to a temporary shelter for the victim’s protection [

17].

Concurrently, judicial actions can be taken under the Laws of Malaysia: Act 574: Penal Code Section 426: Punishment for Committing Mischief, whereby this section states that:

“Whoever commits mischief shall be punished with imprisonment or a term which may extend to *five years or with fine or with both.”

According to [

11], the Domestic Violence Act (1994) and the Penal Code 426 are sufficient to protect victims of domestic violence, but that there are some remaining issues that require further work to overcome problems, which include: (i) the length of time allocated for hearings under two different laws; (ii) the cost that victims must bear for pursuing a legal complaint; and (iii) the amount of compensation to be paid to the victims—particularly for families with reduced economic means.

Although both laws can be applied, one initial problem is that any domestic violence case is difficult to establish in order for justice to take place. Establishing concrete cases of domestic violence cannot be based on hearsay or general observations of victims—such as signs of physical injury or psychological illness resulting from the abuse. Certain experts need to be engaged to prove that domestic violence exists because victims are often psychologically and emotionally controlled by their abusers, and fear implicating their abuser. Victims who suffer domestic violence for extended periods, or from childhood, may be conditioned to believe that the behaviour is commonplace, or even socially acceptable, even if they are subject to severe injuries. Research by the Women and Gender Research Centre [

18] shows that 9 percent of women in relationships suffer domestic violence at least once in their lifetime. According to [

18], 35% of women worldwide have experienced some form of domestic violence by their intimate partner in their lifetime. Ref. [

19] In the Women’s Aid Organisation Annual Report 2020, it showed that 65 percent of girls reported that there was no action taken on the abuser.

4. How to Assist Domestic Violence Victims during MCOs?

Domestic violence may be unavoidable in any society or nation, however, it can be monitored and controlled with suitable initiatives—particularly during MCOs, when everyone is locked down at home with no escape from abusers. There are some significant initiatives that can be implemented, such as providing an appropriate number of shelters for victims, designing a first response system to assist victims immediately when domestic violence happens, and others. The existing laws must be reviewed to ensure that the victims do not have to undergo a long and painful journey to resolve their issues, in order to prevent escalating abuses, including murder.

During MCOs or other crucial situations, shelters must be made available to support victims. This is to ensure that the victims are not forced to remain in abusive situations, nor become homeless, or continue living in uncertainty and fear. After the MCO declarations, shelters for domestic violence were not included as essential services, and therefore were not allowed to operate. This was because the government believed that crowded shelters would facilitate the spread of disease without adequate precautions being taken. The only action that helplines could therefore suggest was for victims to be placed on a waiting list and advised them to get help and protection from other family members, neighbours, or other institutions that are able to assist [

20].

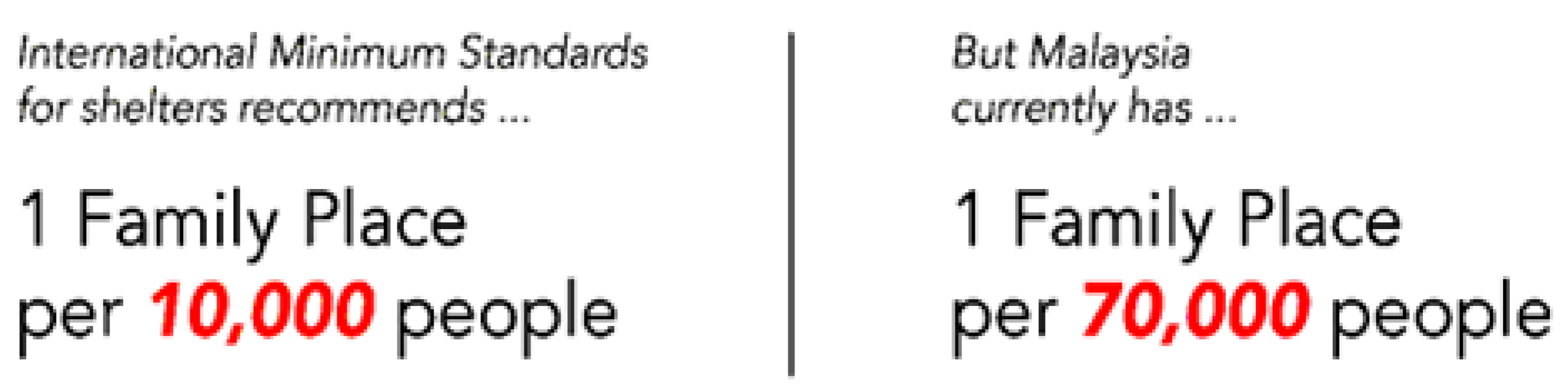

According to [

Figure 2], Malaysia is still far behind other nations in providing shelters for domestic violence victims, with only one family place available for every 70,000 people. The international standard is one family place for every 10,000 people.

The government must take more proactive action in organising temporary shelters for domestic violence victims during pandemic crises. In France, for example, the government converted 20,000 hotel rooms to become shelters and “pop-up counselling centres” after cases of domestic violence increased during their MCO, to ensure the safety of victims of abusive domestic violence.

The effectiveness of Malaysia’s first response system must be significantly improved when domestic violence cases increase during MCOs. First responders include crisis hotline operators, police officers, and social workers. Sufficient manpower resources must be operating to avoid them being overwhelmed as resources for victims to access legal protection and other support. Sufficient funds must be allocated for such services, as the number of cases has been shown to rapidly escalate during a pandemic/MCO.

According to

Figure 3, as of December 2020, Malaysia has a very low ratio of 1:8756 citizens for the numbers of social workers when compared with countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Singapore, or Australia.

Social workers not only cater to domestic violence cases, but also other issues such as flood relief, disaster relief, or other support services, often as volunteers. The quality of services provided to abuse victims is often low, as they are working under the pressure of new social norms, including social distancing and other measures for controlling the pandemic. To ensure an improved quality of support service for domestic violence victims, there is a need to focus on comprehensive coordination among various agencies or parties—particularly during a pandemic. Excessive bureaucratic red tape will only jeopardize the victim safety, and reduce the chance of them getting adequate protection.

Since this short paper only touches the tip of the iceberg that is domestic violence during the COVID-19 MCO in Malaysia, further research must be conducted to enable the country to continue to dig deeper and confront domestic violence while discovering the vulnerabilities of social support systems for protecting families from abuse.