1. Introduction

The Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) has taken many initiatives to raise awareness and educate the community. One of the initiatives is the Malaysia ICT Volunteer (MIV) programme that was initiated in 2016. The MIV aims to empower Malaysians to become digital citizens besides supporting the ‘Smart Digital Nation’ initiative. It focuses on four focus groups, namely MIV with community, MIV with school, MIV with Institutions of Higher Education (IHE), and MIV with international ICT volunteers (IIVs).

The objective of the MIV programme is to impart the positive use of ICT knowledge and encourage digital adoption among communities through MIV volunteers. In a nutshell, the MIV programme promotes and encourages digital and media literacy among citizens. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the MIV programme in promoting positive behaviour use among the MIV volunteers has yet to be assessed. It is imperative to review and assess how effective it is in promoting ICT volunteering behaviour and, in turn, helping the community to improve their digital literacy awareness. Thus, this study aims to measure the effectiveness of the MIV programme in terms of its impact on the MIV volunteers’ behaviour. This study was carried out based on the ICT Volunteering Behaviour model to gauge the effectiveness of the MIV programme based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB).

2. Literature Review

This section will review related works on the relation of TPB and volunteerism. According to the TPB, attitudes towards something can be operationalised using different labels depending on the context [

1]. While Harrison [

2] failed to establish a link between attitudes and intention to volunteer, Okun and Sloane [

3] reported contrasting results. This view is supported by Maes, Leroy, and Sels [

4], who argued that, according to the TPB postulates, entrepreneurial intention and behaviour depend on three factors, one of which is attitude. Similarly, Lee, Reisinger, Kim, and Yoon [

5] and Chua, Meng, Ryu, and Han [

6] found that positive attitudes towards volunteering enhance the likelihood of working as a volunteer even in the long term. This study therefore hypothesised:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Attitude Towards MIV has an influence on Intention to Volunteer.

Subjective Norms influence the Intention to Volunteer via social pressure, as individual behaviours are often guided by the opinions of significant others [

7]. According to Brayley et al. [

8], Subjective Norms are essential for a person to decide whether to be a volunteer. Based on their study, one will continue to volunteer in the mentoring programme if they can feel the support of significant others towards them. Even regarding intention towards purchasing green food, it was found that Subjective Norms have a significant correlation with the intention to purchase [

9]. It is because people tend to consider other people’s perspectives and expectations on their behaviour and are concerned about how people will behave. Thus, when making a decision Subjective Norms have an influence on them. Thus, this study hypothesised:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Subjective Norms have an influence on Intention to Volunteer.

According to the TPB, human behaviour is guided by behavioural, normative, and control beliefs, which will in turn give rise to perceived behavioural control [

10]. Randle and Dolnicar [

11] found that Perceived Behavioural Control was among the most important influential factors on volunteering intentions. France et al. [

12] similarly noted that Perceived Behavioural Control was strongly related to one’s intention to donate blood. Perceived Behavioural Control was identified as a reliable predictor of Perceived Behavioural Control by several authors, including Warburton and Terry [

1], Lee, Won, and Bang [

13], and Reuveni and Werner [

14]. Thus, this study hypothesised:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Perceived Behavioural Control has an influence on Intention to Volunteer.

ICT Volunteering Behaviour is a special form of prosocial behaviour geared toward helping others, often through non-profit organisations [

15]. According to Ajzen [

10], stronger functional beliefs related to volunteering will lead to a stronger Intention to Volunteer and thus the actual prosocial behaviour. In an earlier study, Ajzen [

16] found that intention is a reliable predictor of behaviour and these findings were later confirmed by Hagger, Chatzisarantis, and Biddle [

17], and Sheeran [

18]. Teo and Lee [

19] also found that pre-service teachers’ intention to use technology was influenced by their behaviour toward computers, while Ayob, Sheau-Ting, Jalil, and Chin [

20] established that intention leads to better waste management. Therefore, this study hypothesised:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Intention to Volunteer has an influence on ICT Volunteering Behaviour.

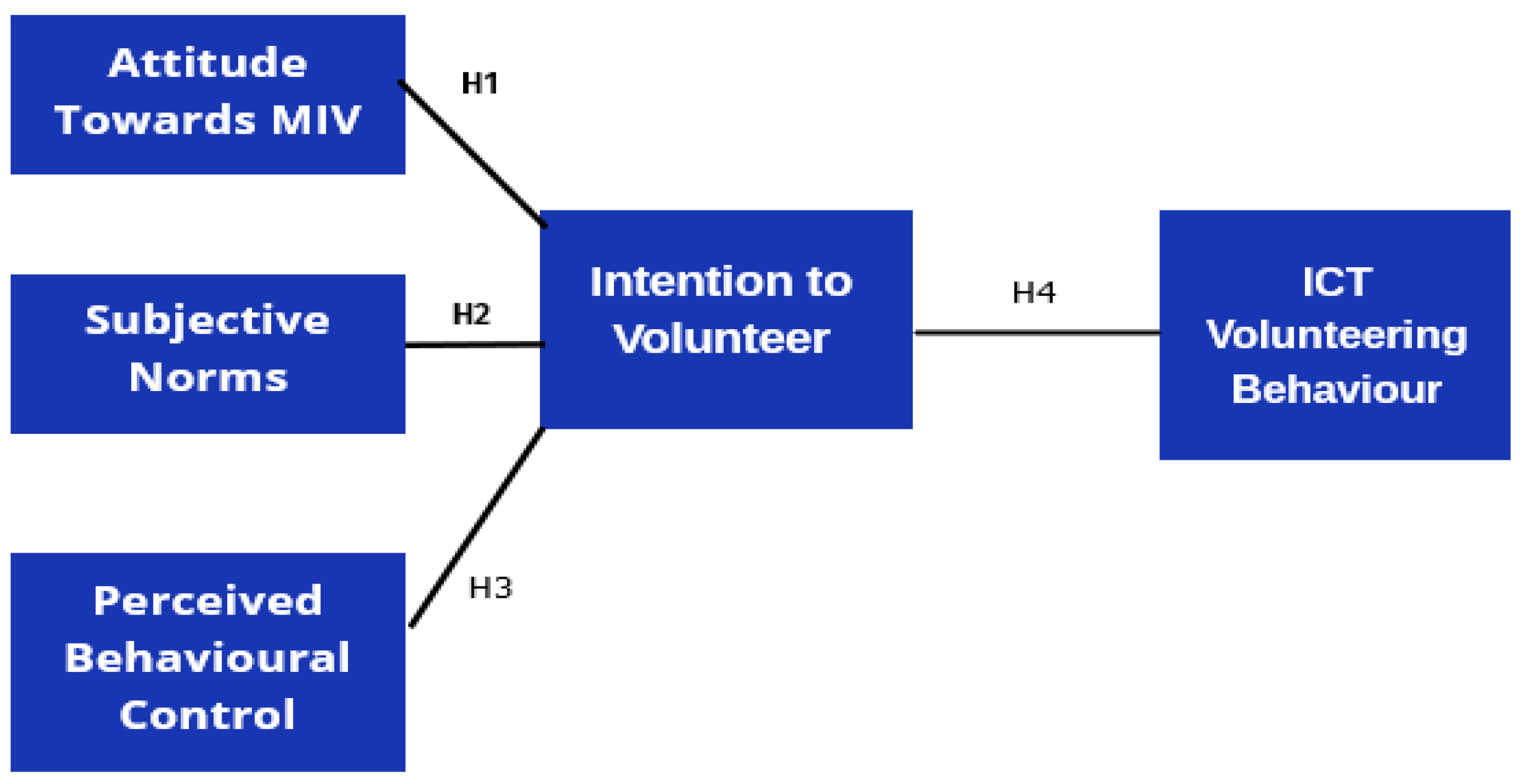

Based on the reviews, the following

Figure 1 illustrates the research model that comprises four predictors (Attitude Towards MIV, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioural Control, and Intention to Volunteer) and a dependent variable (ICT Volunteering Behaviour).

In general, this proposed research model depicted in

Figure 1 describes how the MIV programme would influence the ICT volunteering behaviour among MIV volunteer participants. It posits that three antecedent constructs (Attitude Towards MIV, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioural Control) will positively impact the Intention to Volunteer. Finally, the increase in Intention to Volunteer should improve the ICT Volunteering Behaviour of the participants.

3. Methodology

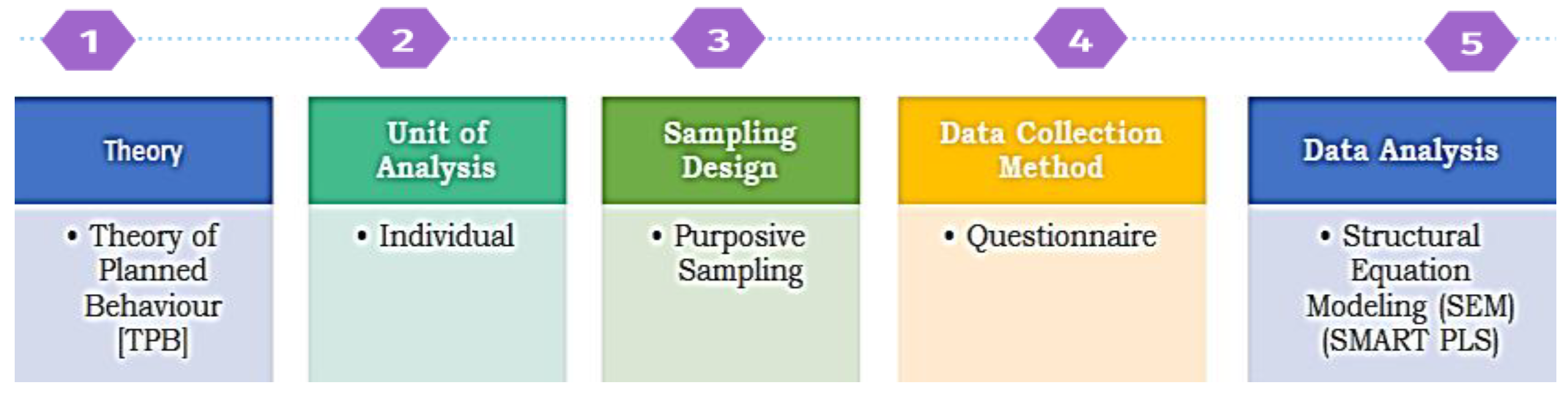

This section describes the steps involved in achieving the study’s objectives.

Figure 2 shows the research design used in this study. The quantitative approach was applied in this study based on the research objectives. To examine the relationships between variables, this study proposed four hypotheses as the research model. Thus, the use of such an approach is appropriate since quantitative studies usually investigate the relationships between variables and occasionally explain the causes of those relationships [

21].

A survey is considered the most appropriate method because of its accuracy in gathering information and enabling researchers to generalise findings, from a sample to a population [

22]. It is also appropriate for studies with large sample sizes, as it is expedient, cost-effective, and administratively efficient [

23]. Finally, a survey is also relevant when querying respondents about their perceptions, opinions, and feelings [

24], which fits the nature of this study. The potential respondents were invited via email invitations, and an online survey is used to capture responses from respondents during the data collection period. This method allows this study to gain a faster and higher response rate while permitting real-time data monitoring [

25].

3.1. Research Instrument

The outcome of the initial theoretical investigation was later used to develop the instruments to measure the effectiveness of the MIV programme. The instruments consist of a set of statements that were adapted from several sources and reformulated to suit the perspective of this study. Additionally, face validation, content validation, and pilot study were employed during the instrument development stage to produce a valid and reliable instrument. The instrument comprises two main parts: (i) Part A: Respondent Demographics; and (ii) Part B: MIV programme Evaluation.

To facilitate the understanding among respondents, the items are presented in two languages, Malay and English. The measurement scale for every construct is a seven-point numerical scale, which ranges from 1 to 7 (‘1’ extremely disagree to ‘7’ extremely agree). The scale is applied because it provides a wider range and prevents respondents from selecting the neutral value. Thus, the chances of bias will be decreased [

26].

3.2. Data Collection

Once a valid and reliable instrument was successfully produced, the study proceeded with the data collection procedures. The main data collection was undertaken from August to October 2021. The respondents were MIV volunteers that were selected from the list of MIV volunteers given by the MCMC. The MIV volunteers answered the online survey through the URL link provided:

https://bit.ly/MIV-VOLUNTEER (accessed on 31 October 2021).

3.3. Data Analysis

The gathered data was analysed using statistical techniques to validate the research model that was developed based on the TPB model. Accordingly, the descriptive statistics and PLS-SEM were used to discover participants’ change in behaviours prior to the MIV programme. This data analysis phase was completed in two stages. Both datasets underwent data cleaning and preparation procedures: (i) outliers, (ii) multicollinearity, and (iii) normality. Next, the main analysis began with two types of descriptive statistics for respondents and constructs of this study. Finally, the PLS-SEM analysis was performed in two stages: the Measurement Model and Structural Model. The research model based on the TPB Model was validated using PLS-SEM during the implementation phase. Finally, the results of the survey were reported and presented to the MCMC.

4. Results

This study aimed to investigate the behavioural changes triggered by MIV programmes among MIV volunteers. In order to make sense of the statistical findings produced in the prior stage, the interpretation and discussion were carefully and critically completed during the last stage of this study. This stage also highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of the current implementation of MIV programmes, along with suggestions for future improvements. These were completed based on empirical findings yielded from the descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. At the end of the data collection period, this study managed to gather 415 responses. During the cleaning procedures, 86 deletions were made, thus, producing 329 valid cases for the final PLS-SEM analysis.

This section presents a summary of demographic information of the respondents based on the returned questionnaires. The information obtained from the survey included the phone number, name, email, age, gender, race, highest education, and working status. From the survey, 329 respondents of Malaysia ICT Volunteers (MIV) aged between 18 years old and above 50 years old answered the questionnaires. Out of 329 respondents, 263 respondents are female volunteers (79.94%) and another 66 respondents are male volunteers (20.06%). From the data collected, the majority of the respondents were aged between 31 and 40 years old (150 respondents, 45.59%), 96 respondents were aged between 26 and 30 years old (29.18%), 64 respondents were aged between 18 and 25 years old (19.45%), 18 respondents were aged between 40 and 50 years old (5.47%), and 1 respondent was aged > 50 years old (0.30%).

Moreover, the respondents are of different races, where most of the respondents are Malay (231 individuals, 70.22%), while 97 respondents (29.48%) are of other races (Siam, Bajau, Banjar, Bidayuh, Bugis, Brunei, Cocos, Dusun, Iban, Iranun, Jawa, Kadazan, Kadazan Dusun, Kenyah, Kimaragang, Kedayan, Kayan, Kagayan, Lunbawang, Murut, Rungus, Salako, Sino, Siam, Sungai, Suluk, and Tidung), and only 1 respondent (0.30%) is Chinese. Regarding highest education, 183 respondents (55.62%) have a degree, 79 respondents (24.01%) have a diploma, 52 respondents (15.81%) SPM/SPMV/STPM/Foundation, 12 respondents (3.65%) have a Master’s degree, 1 respondent (0.30%) Sijil Kemahiran Malaysia, 1 (0.30%) SRP, and another 1 UPSR (0.30%). Lastly, regarding the working status, most of the volunteers work full-time in private sectors, which was 220 respondents (66.87%). Secondly, 26 volunteers are students (7.90%), followed by 25 volunteers (7.60%) working in a full-time government/agency position. Then, 14 respondents (4.26%) were self-employed, 12 (3.64%) housewives, 11 respondents (3.34%) were unemployed, 2 respondents (0.61%) were self-employed and housewives, 2 respondents (0.61%) were students and had full-time government/agency positions, and another 2 respondents (0.61%) were in part-time government employment, while the rest of the 15 respondents (4.56%) had another working status or double working status.

Table 1 indicates a summary of the demographic information of the respondents.

Structural Equation Modelling

The measurement model was examined for construct reliability and validity. First, the construct reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR), with the recommended value of 0.700 [

27]. The result shows that Perceived Behavioural Control has the lowest construct reliability (CA = 0.906, CR = 0.925) while the highest belongs to Intention to Volunteer (CA = 0.970, CR = 0.977). Thus, the results illustrate that the indicators used to present the construct have desirable internal consistency reliability. Second, the constructs’ validity was evaluated through convergent and discriminant validity. In this study, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was tested to examine the convergent validity. The results indicate that the AVE values range between 0.640 and 0.894, which were all higher than the suggested value of 0.500. Given these results, the convergent validity is ascertained. This study employed the HTMT criterion for assessing the discriminant validity. The HTMT criterion is considered to be satisfied as all the values were below the accepted value of 0.900. Therefore, the discriminant validity was established.

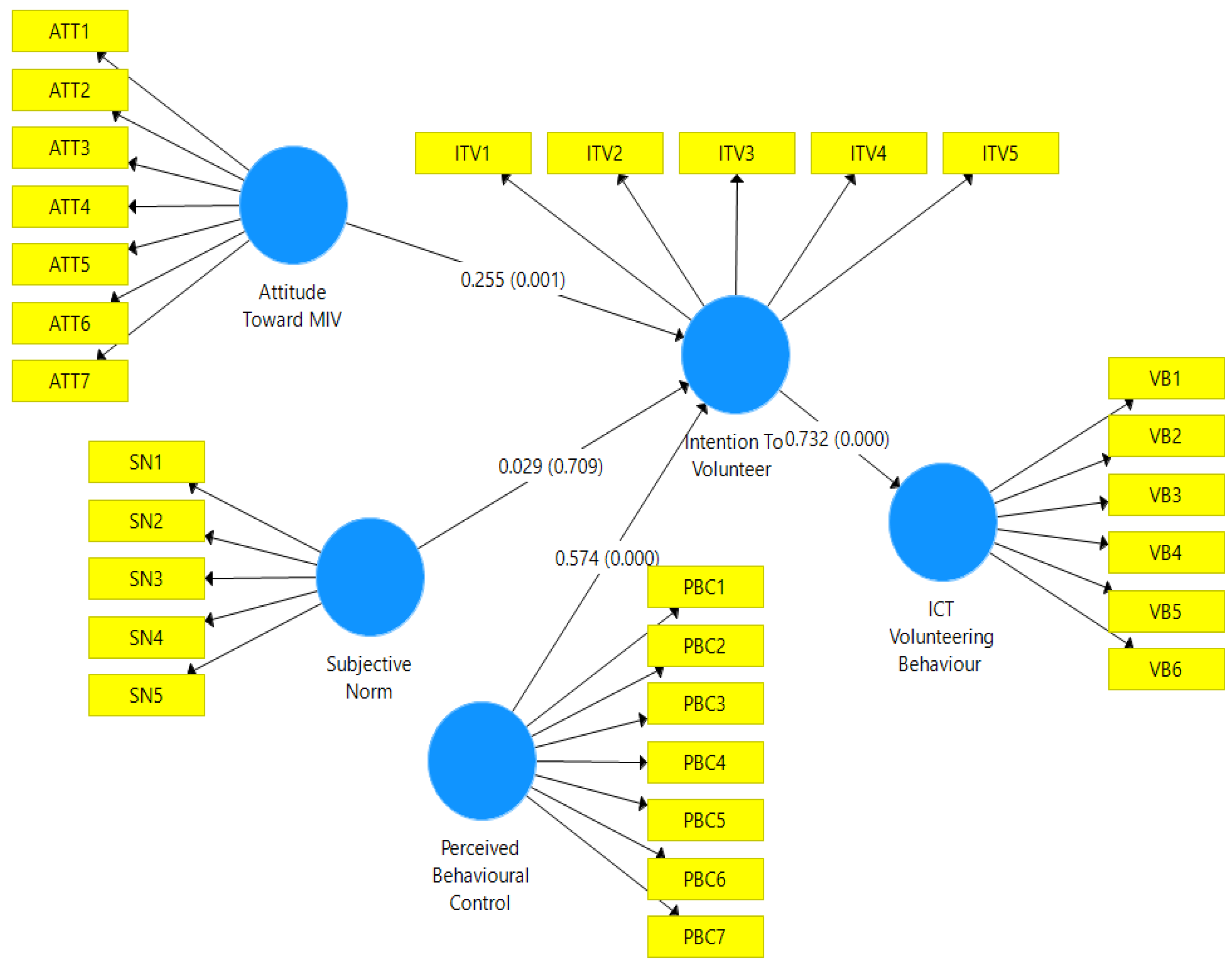

After the CFA that was completed during the measurement model analysis, the structural model was examined. The conceptual model of this study consists of four hypotheses. The R2 values were 0.618 and 0.497 for Intention to Volunteer and the ICT Volunteering Behaviour, respectively. It is suggested that 61.8% of the variance in MIV Awareness can be explained by Attitude towards MIV, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioural Control. Furthermore, 49.7% of the variance in Digital Literacy Behaviour can be explained by MIV Awareness.

Table 2 summarises the assessment of four hypotheses in the structural model.

Hypothesis H1 postulated that ATT significantly influences the ITV among MIV volunteers. From the analysis, it was discovered that this relationship is significant (β = 0.255, t = 4.409,

p < 0.01). Therefore, this finding supports hypothesis H1. However, the result shows that SN did not significantly affect ITV (β = 0.029, t = 1.400,

p = 0.709), which returned the hypothesis H2. Meanwhile, hypothesis H3 posited that PBC would significantly influence the ITV. The analysis shows that this hypothesis is supported (β = 0.574, t = 7.664,

p < 0.01), thus, supporting the proposed hypothesis. Similarly, hypothesis H4 which postulated a significant relationship between ITV and VB is also supported (β = 0.732, t = 17.924,

p < 0.01) in this study.

Figure 3 illustrates the bootstrapping analysis of the structural model for MIV volunteers.

5. Discussion

The study findings indicate that the MIV volunteers are committed to volunteering in their community, school, MIV, and institutions of higher education because they are aware of the importance of promoting digital and media literacy, thus, supporting H1 and concurring with the results reported by Edelman [

28]. ICT volunteering is increasingly recognised as the effective means of promoting digital literacy at the global level, as this allows the local talents, ideas, insights, and resources to be leveraged to enhance innovation and influence community attitudes toward digital literacy. However, as volunteers’ subjective norms (i.e., opinions of friends and family and other influential individuals) were found not to affect their intention to volunteer, H2 is not supported. These results are also countered by the findings reported by other authors [

29,

30,

31], possibly due to the differences in the research aims and the methodology adopted, or the participants’ characteristics.

As noted by Knabe [

32], the decision to volunteer in MIV programmes is guided by individual judgment. This is consistent with the current study finding that Perceived Behavioural Control Influences Intention to Volunteer, thus, supporting H3. Nonetheless, to sustain volunteers’ motivation, they should be offered appropriate financial or non-financial awards [

33], and their efforts should be recognised more explicitly, via appreciation letters from MCMC superiors or similar initiatives. In terms of the MIV programme’s ability to impact the MIV volunteering behaviour, the analyses revealed that this influence was exerted via Intention to Volunteer, thus, supporting H4 and concurring with available evidence [

34,

35]. Hence, to ensure that volunteers remain engaged in this and other ICT initiatives in Malaysia, strategies for improving their willingness, effort, readiness, and confidence should be investigated.

6. Recommendations

There is a need to identify the ways to or factors that attract more volunteers to be involved in the MIV programme in terms of improved, better rewards, global recognition, and a proper ICT volunteerism policy. To sustain volunteer motivation, it is necessary to adopt a suitable award system, while continuing to improve the ICT programme quality by partnering with diverse stakeholders such as schools, higher institutions, private and public agencies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

The MIV volunteers would also benefit from the adoption of a Digital Volunteer Champion, which would allow more experienced individuals to teach new recruits. They should also be encouraged to share their ideas with their peers and promote ICT to their family and friends while actively engaging in the MIV programme recruitment. For this purpose, social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, etc., can be used alongside other marketing strategies, including hashtag projects, online interactive quizzes, and online gamification. The MCMC should also consider customising the MIV digital literacy module to different age and aptitude levels, starting with children, teenagers, and the elderly, as this will increase interest in participation as well as the benefits derived from the programme.

7. Conclusions

As MIV programmes rely on volunteers, it is essential to ensure their continued commitment, which can be achieved by a better-designed reward and recognition system, as well as opportunities to network and collaborate with ICT volunteers in other parts of the world. Moreover, even though digital literacy is important for the social growth of communities and the economic prosperity of nations, the effectiveness of such ICT programmes has not been extensively studied. This gap in extant knowledge was addressed in the present study. The findings indicate that attitude towards MIV, subjective norms, perceived behaviour control, intention to volunteer, and ICT volunteering behaviour can potentially influence digital and media literacy at both individual and community levels. Thus, it is essential to develop new ways of promoting the MIV programme to the wider community to increase the number of potential participants as well as MIV volunteers. It is also important to forge relationships with relevant entities that can provide knowledge and resources for the MIV programmes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.O. and H.I.; methodology, M.A. and H.A.; validation, A.Y. and A.A.; formal analysis, M.O. and H.I.; investigation, M.A and H.A.; resources, A.Y. and A.A; writing—original draft preparation, M.O., H.I., M.A., H.A., A.Y. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.O., H.I., M.A. and H.A.; project administration, M.O.; funding acquisition, M.O., H.I., M.A., H.A., A.Y. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) under the Digital Society Research Grant (DSRG) programme [S/O Code: 14972].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission through the Digital Society Research Grant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Warburton, J.; Terry, D.J. Volunteer decision making by older people: A test of a revised theory of planned behavior. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 22, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A. Volunteer motivation and attendance decisions: Competitive theory testing in multiple samples from a homeless shelter. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, E.S.; Sloane, M.A. Application of planned behavior theory to predicting volunteer enrollment by college students in a campus-based program. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2002, 30, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, L.; Leroy, J.; Sels, H. Gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions: A TPB multi-group analysis at factor and indicator level. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Reisinger, K.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, M.J. The influence of volunteer motivation on satisfaction, attitudes, and support for a mega-event. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, H.; Meng, B.L.; Ryu, B.; Han, H.B. Participate in volunteer tourism again? Effect of volunteering value on temporal re-participation intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, K.S.; Courneya, R.E. Investigating multiple components of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived control: An examination of the theory of planned behavior in the exercise domain. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 42, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayley, N.M.N.; Obst, P.L.; White, K.M.; Lewis, I.M.; Warburton, J.; Spencer. Examining the predictive value of combining the theory of planned behaviour and the volunteer functions inventory. Aust. J. Psychol. 2015, 67, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, A.F.; Jeger, M.; Ivković, M. The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase green food. Econ. Res. -Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randle, S.; Dolnicar, M. Does cultural background affect volunteering behavior? J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2009, 21, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, H.J.; Kowalsky, L.; France, J.M.; McGlone, C.R.; Himawan, S.T.; Kessler, L.K.; Shaz, D.A. Development of common metrics for donation attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and intention for the blood donation context. Transfusion 2014, 54, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Won, Y.J.; Bang, D. Why do event volunteers return? Theory of planned behavior. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2014, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveni, P.; Werner, Y. Factors associated with teenagers’ willingness to volunteer with elderly persons: Application of the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, D.T.; Shek, B.M. Beliefs about volunteerism, volunteering intention, volunteering behavior, and purpose in life among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Sci. World J. 2009, 9, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, S.J.; Chatzisarantis, M.S.; Biddle, N.L. The influence of autonomous and controlling motives on physical activity intentions within the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention—behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, C.B.; Lee, T. Explaining the intention to use technology among student teachers: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2010, 27, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, H.C.; Sheau-Ting, S.F.; Jalil, L.; Chin, R.A. Key Determinants of Waste Separation Intention: Empirical Application of TPB. Facilities 2017, 35, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, N.E.; Wallen, J.R. The nature of qualitative research: How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, R.; Bougie, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 5th ed.; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: West Sussex, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shaughnessy, J.J.; Zechmeister, E.B.; Zechmeister, J.S. Research Methods in Psychology, 9th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, P.; Schindler, D. Business Research Methods, 10th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, B.; Papazafeiropoulou, Y.K.; Brinkman, A.; Lal, W.P. Examining the influence of service quality and secondary influence on the behavioural intention to change internet service provider. Inf. Syst. Front. 2010, 12, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, M.; Hult, J.F.; Ringle, G.T.M.; Sarstedt, C.M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, B. GE Global Innovation Barometer 2014 Edition—Global Report; GE: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, I.V.; Curmi, F.; Said, E. Influencing Factors Affecting Young People’s Attitude Towards Online Advertising: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2021, 11, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shahzad, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Abdullah, M.; Hassan, N.M. Trust and Consumers’ Purchase Intention in a Social Commerce Platform: A Meta-Analytic Approach. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221091262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabe, A. Applying Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior to a Study of Online Course Adoption in Public Relations Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, L.; Nummenmaa, D. Reward and emotion: An affective neuroscience approach. In current opinion in behavioral sciences. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 39, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V.; Allen, D.G.; Shipp, A.J. Time to leave? The interaction of temporal focus and turnover intentions in explaining voluntary turnover behaviour. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).