Abstract

Background: Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are considered common facilitating factors along with other infections in triggering febrile seizures (FS). The main purpose of our study was to identify specific patterns of UTIs, using a combination of inflammatory biomarkers, in order to differentiate UTIs from other bacterial diseases triggering FS. Method: This study included a number of 197 distinct FS events from patients hospitalized in the Pediatric Clinical Hospital Sibiu, among which 10.2% were diagnosed with UTIs. Results: In one-third of the patients with UTI, the symptoms were limited to fever and FS. Using Two-Step cluster analysis, a distinct inflammatory pattern has emerged: higher platelet distribution of the population (PDW), platelet large cell ratio (P-LCR), mean platelet volume (MPV), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR). This pattern was associated mainly with bacterial lower respiratory infections. UTIs were highly unlikely in the patients with significantly increased CRP values and normal values of platelet indices. Conclusion. Considering the nonspecific clinical picture of UTIs at an early age, to optimize the management of FS, a fast diagnosis of UTI is mandatory. Our study suggests that analyzing the inflammatory biomarkers interlinks (rather than individual parameters) could help identify even oligosymptomatic UTIs patients.

1. Introduction

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) has defined Febrile Seizure (FS) as a seizure occurring in childhood after one month of age, associated with a febrile illness not caused by an infection of the central nervous system, without previous neonatal seizures or a previous unprovoked seizure, and not meeting criteria for other acute symptomatic seizures [1].

Febrile seizures are the most common childhood neurological disorders and an important health problem with potential short- and long-term complications [2]. There is a lack of studies regarding the association between febrile seizures and other bacterial etiologies, such as urinary tract infections. The goal of our study was to identify specific patterns of urinary tract infections (UTIs), using a combination of inflammatory biomarkers, in order to differentiate UTIs from other bacterial diseases associated with FS.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the Sibiu Pediatric Clinical Hospital, associated with a larger project (Phd thesis) on febrile seizures (see details in References [3,4,5]). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital. The study group was represented by a number of 136 patients with 197 distinct febrile seizure events. We used the age criterion according to the revised definition of ILAE, referring to the age range between one month and five years. Simple febrile seizures were defined as generalized seizures lasting less than 15 min and no recurrence within 24 h. Complex febrile seizures were diagnosed based on the presence of at least one criterion from the following: focal appearance, duration over 15 min, and multiple seizures within 24 h [1].

Data on patient’s general characteristics, seizures’ pattern, infectious etiology, biological parameters were analyzed as possible predictors for the UTIs status of febrile seizures children. The analysis was conducted using SPSS v.20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical difference was considered for p< 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. General Description

We enrolled 136 children in the studied group, with an average age of 23.23 ± 12.43 months and a balanced gender distribution (50.8% boys). There were 197 distinct seizure events, of which 156 (79.2%) were with simple febrile seizures and 41 (20.8%) with a complex pattern. The main seizure duration ranged between 1–5 min and 58.3% from the total febrile seizures events were preceded by temperatures higher than 39 °C. We noticed only in a small number of cases (4.1%) a higher than 72 h time interval from fever occurrence to seizure onset. A more detailed presentation of the results can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the demographic and clinical data.

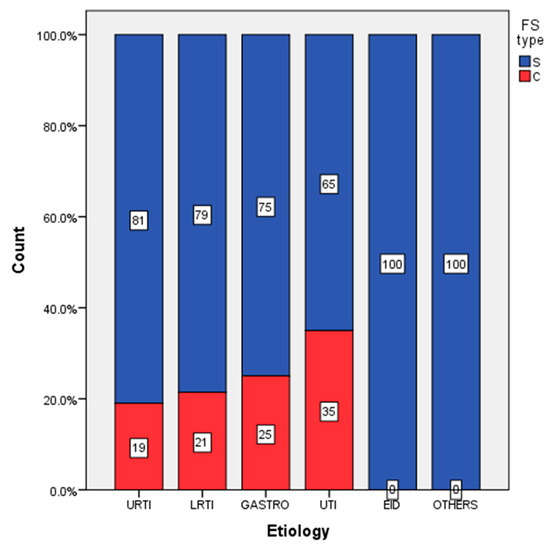

Complex febrile seizures were reported in a higher percentage of children from the UTIs group (35%) comparing to the non-UTIs group (gastroenteritis subgroup 25%, acute upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) subgroup 21.43%, acute lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) group 19.01%) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of simple and complex febrile seizures according to etiology (upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), urinary tract infections (UTI)).

3.2. Laboratory Data and Two-Step Cluster Analysis Results

When comparing the UTIs group with the non-UTI group, individual assessment of values of individual laboratory data parameters did not identify statistically significant differences between groups, except for the C-Reactive Protein (CRP) which had higher values in the UTIs group by comparison to the non-UTI group (see more details in Reference [4]).

Further, we performed a Two-Step Cluster analysis for the whole cohort of patients, using as segmentation variables the inflammatory biomarkers: CRP, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), plachetocrit (PCT), platelet large cell ratio (P-LCR), platelet distribution of the population (PDW), mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet counts (PLT). The clustering method identified four distinct groups of patients. Among resulted clusters, a group with distinct inflammatory patterns has emerged: higher PDW, P-LCR, MPV, CRP, and NLR. This pattern was associated mainly with bacterial lower respiratory infections-cluster 3. UTIs were highly unlikely in the patients with significantly increased CRP values and normal values of platelet indices. The identified groups’ profiles in terms of demographical and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Groups profile in terms of demographical and clinical characteristics.

The demographic and clinical cluster profile reveals males predominance in cluster 4 (UTI) while females in cluster 3 (respiratory bacterial). The maximum age group incidence is between 13–24 months in patients from both clusters. Most patients in cluster 4 (UTI) have a moderate febrile rise at seizure onset (between 38–39 °C), with the percentage being slightly lower in patients with respiratory bacterial infections (cluster 3). In both clusters, most seizures lasted between 1 and 5 min, while 21.43% of patients in cluster 3 and 14.29% of patients in cluster 4 have prolonged seizures (duration > 15 min). Simple febrile seizures predominate in both clusters, representing 64.29% of the cohort. There is a similar percentage of recurrence of seizures in the first 24 h in both clusters.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

We report a UTI prevalence of 10.7%, comparable to that of other studies [6,7,8]. The results of our study that the most common etiological agents of UTIs are bacteria of enteric origin correlate with the results of other epidemiological studies [9,10,11,12,13]. While analysis of individual inflammatory parameters provided limited knowledge on UTIs in febrile seizures, the cluster analysis identifies four clusters with distinct inflammatory pattern in relation to the etiology of the infectious context profiling a distinctive pattern associated mainly with bacterial lower respiratory infections and highly unlikely UTIs bacterial etiology based on a higher CRP but with normal platelets indices. Our findings emphasize the practical importance of unsupervised machine learning in hasting the etiology diagnosis for febrile seizures in children.

Author Contributions

R.C. conceived, designed, and coordinated the study, performed data acquisition, interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript; I.M. performed data analysis and participated in drafting the manuscript; L.D. participated in data acquisition and provide useful suggestions; C.B. provided useful suggestions; B.M.N. participated in analyzing the data, drafting and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the principles of good clinical practice. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pediatric Clinical Hospital Sibiu, approval code and date 6000/12.10.2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors, upon reasonable request, with the permission of the institution

Acknowledgments

This work is related to the PhD thesis of candidate Raluca Maria Costea under the supervision of Mihai Leonida Neamtu. It has been conducted in the Pediatric Clinic Hospital Sibiu, within the Research and Telemedicine Center in Neurological Diseases in Children-CEFORATEN project (ID 928 SMIS-CSNR 13605) financed by ANCSI with the grant number 432/21.12.2012 through the Sectoral Operational Program “Increase of Economic Competitiveness”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- International League against Epilepsy. Guidelines for epidemiologic studies on epilepsy, Commission on Epidemiology and prognosis. Epilepsia 1993, 34, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, K.B.; Calik, M.; Karal, Y.; Isikay, S.; Kocak, O.; Ozcelik, A.; Yazar, A.S.; Nuhoglu, C.; Sag, C.; Kilic, O.; et al. Viral etiological causes of febrile seizures for respiratory pathogens (EFES Study). Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 15, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, R.; Maniu, I.; Dragomir, A.; Banciu, D.D.; Neamtu, B.M. Cluster Analysis a Profiling Tool in Children With Febrile Seizures. In Proceedings of the 2019 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB), Iasi, Romania, 21–23 November 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniu, I.; Costea, R.; Neamtu, B.M. Cut-off Values for Biomarkers. A Review of Statistical Methods and an Application Study on the Association Between UTI and CRP in Febrile Seizure. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conference on E-Health and Bioengineering (EHB 2020), Iasi, Romania, 29–30 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Costea, R.M.; Maniu, I.; Dobrota, L.; Neamtu, B. Stress Hyperglycemia as Predictive Factor of Recurrence in Children with Febrile Seizures. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi, A.; Ashrafi, M.; Moghtaderi, M. Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection among Children with Febrile Convulsion. Int. J. Nephrol. Kidney Fail. 2017, 3, 16966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminezhad, B.; Taghinejad, H.; Borji, M.; Seymohammadi, R. Evaluation of the Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection in Children with Febrile Seizure. J. Compr. Pediatr. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, N.; Morone, N.E.; Bost, J.E.; Farrell, M.H. Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection in Childhood. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2008, 27, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chon, C.H.; Lai, F.C.; Shortliffe, L.M.D. Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 48, 1441–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigore, N.; Pirvut, V.; Totan, M.; Bratu, D.; Mitariu, S.I.C.; Mitariu, M.C.; Chicea, R.; Sava, M.; Hasegan, A. The Evaluation of Biochemical and Microbiological Parameters in the Diagnosis of Emphysematous Pyelonephritis. Rev. Chim. 2017, 68, 1285–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegan, A.; Totan, M.; Antonescu, E.; Bumbu, A.G.; Pantis, C.; Furau, C.; Urducea, C.B.; Grigore, N. Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infections in Children and Changes in Sensitivity to Antibiotics of E. coli Strains. Rev. Chim. 2019, 70, 3788–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, P.; Gopu, S.; Krishna, V.; Kumar, M. A Study of Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection among Children with Febrile Seizures in a Tertiary Care Hospital. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2017, 16, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.S.; Reynolds, K.L. Community-Acquired Bacteremic Urinary Tract Infection: Epidemiology and Outcome. J. Urol. 1984, 132, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).