Co-Inocula Assays of Yeasts with “Killer” Pheno-Type and Sensitive Strains of Saccharomyces cere-visiae with Defects in Mannoprotein Synthesis †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

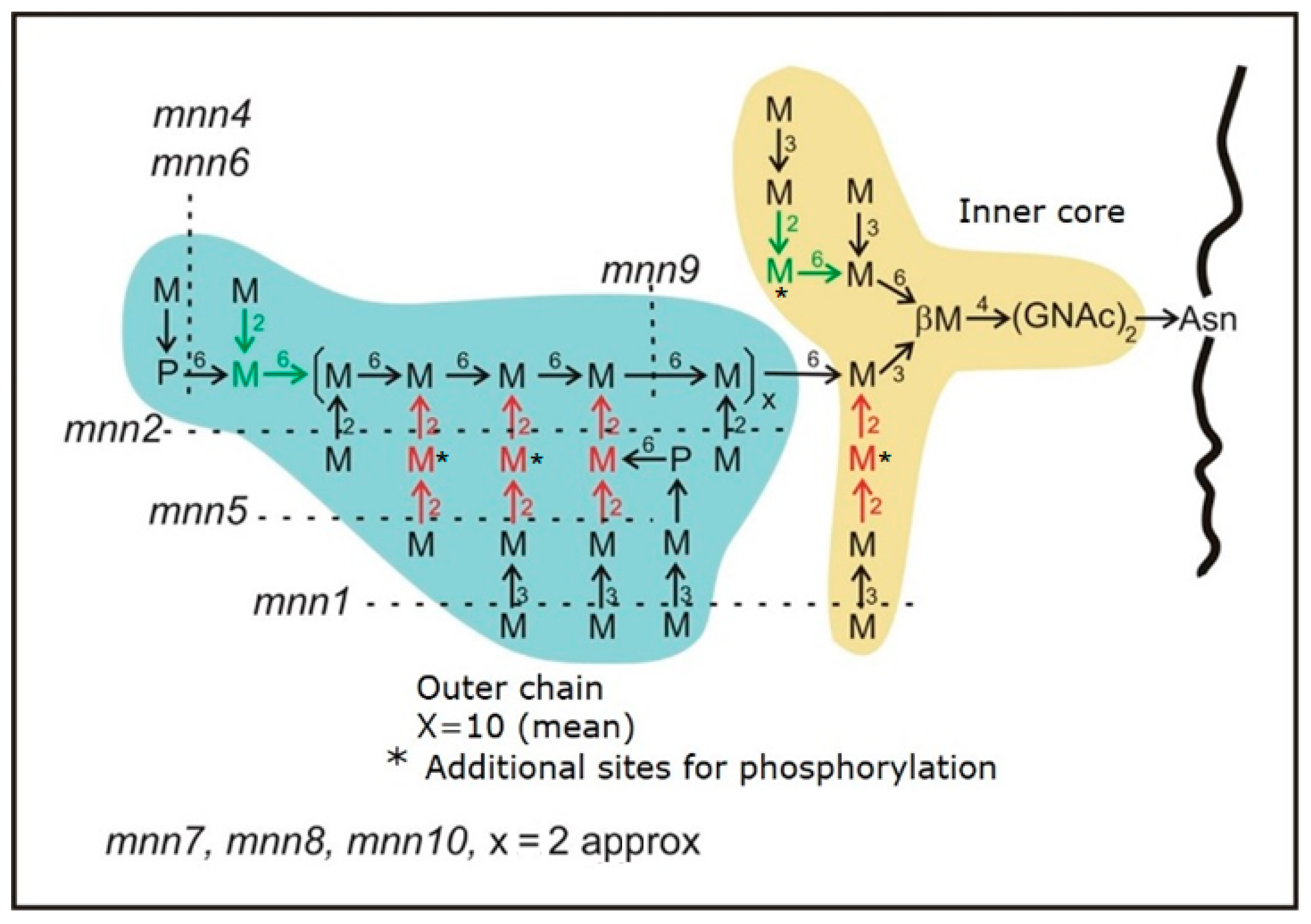

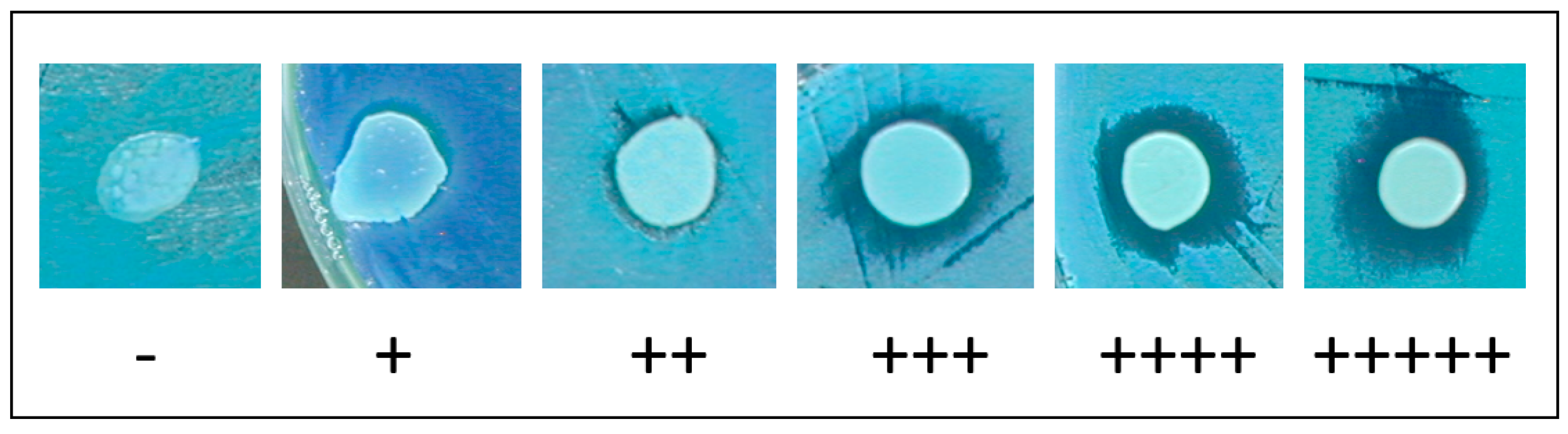

3.1. The More Affected the Mannoprotein Is, the More Sensitive It Is to the Killer Toxin

3.2. The mnn1 Mutation in Combination with Other mnn Improves Killer Resistance

3.3. Kbarr1 Is a Good Killer Candidate for Co-Inocula

4. Conclusions

- (a)

- Once the relation of the size charge of mannoprotein and effects is clarified, it will be possible to choose mannoproteins on demand (size charge) in order to improve some characteristics of wine, like reducing tartaric or protein precipitation, or improving clarification, mouthfeel, aroma, etc.

- (b)

- The use of co-inocula with the mutants which synthesize the desired mannoprotein and the appropriate killer strain will allow the direct release of mannoprotein from the mutant, avoiding the purification step.

- (c)

- Torulaspora delbruekii EX1180 (Kbarr1) has proved to be a good candidate to be used as the killer counterpart of the co-inoculum.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexandre, H.; Guilloux-Benatier, M. Yeast autolysis in sparkling wine—A review. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2006, 12, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebollero, E.; Rejas, M.T.; Gonzalez, R. Autophagy in wine making. In Autophagy: Lower Eukaryotes and Non-Mammalian Systems, Ptar A; Elsevier Academic Press Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 451, pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ballou, C.E. Isolation, characterization and properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mnn mutants with nonconditional protein glycosylation defects. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 185, 440–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wickner, R.B. Double-stranded RNA viruses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 60, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqueda, M.; Zamora, E.; Alvarez, M.L.; Ramirez, M. Characterization, ecological distribution, and population dynamics of Saccharomyces sensu stricto killer yeasts in the spontaneous grape must fermentations of Southwestern Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, M.; Velazquez, R.; Maquedal, M.; Lopez-Pineiro, A.; Ribas, J.C. A new wine Torulaspora delbrueckii killer strain with broad antifungal activity and its toxin-encoding double-stranded RNA virus. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| pH | T | wt | mnn1 | mnn2 | mnn3 | mnn5 | mnn6 | mnn9 | mnn10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5 | 13 °C | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++++ | ++++ |

| 25 °C | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | ++++ | ++++ | |

| 4 | 13 °C | ++++ | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ |

| 25 °C | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++++ | ++++ | |

| 4.7 | 13 °C | ++ | + | + | +++ | + | + | ++++ | ++ |

| 25 °C | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++++ | + |

| pH/T | mnn1 | mnn6 | mnn10 | mnn1mnn10 | mnn6mnn10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5/13 °C | + | +++ | ++++ | + | ++++ |

| 4/13 °C | + | ++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ |

| 4.7/13 °C | + | + | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Killer | Strains | wt | mnn1 | mnn2 | mnn3 | mnn5 | mnn6 | mnn9 | mnn10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | F166 | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| K2 | E7AR1 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++++ | +++ |

| K28 | F182 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| klus | EX229 | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - |

| kbarr1 | EX1180 | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++++ | ++++ |

| kbarr2 | EX1257 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| no killer | 2K- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Killer | Strains | mnn1mnn6 | mnn1mnn2 | mnn2mnn6 | mnn6mnn10 | mnn1mnn10 | mnn1mnn9 | mnn2mnn10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | F166 | ++ | + | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| k2 | E7AR1 | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | - | ++++ | +++ |

| K28 | F182 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| klus | EX229 | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + |

| kbarr1 | EX1180 | ++ | + | +++ | ++++ | + | ++++ | + |

| kbarr2 | EX1257 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| no killer | 2K- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gil, P.; Martínez, A.; Bautista, J.; Velázquez, R.; Ramírez, M.; Hernández, L.M. Co-Inocula Assays of Yeasts with “Killer” Pheno-Type and Sensitive Strains of Saccharomyces cere-visiae with Defects in Mannoprotein Synthesis. Proceedings 2021, 70, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods_2020-07732

Gil P, Martínez A, Bautista J, Velázquez R, Ramírez M, Hernández LM. Co-Inocula Assays of Yeasts with “Killer” Pheno-Type and Sensitive Strains of Saccharomyces cere-visiae with Defects in Mannoprotein Synthesis. Proceedings. 2021; 70(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods_2020-07732

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil, Patricia, Alberto Martínez, Joaquín Bautista, Rocío Velázquez, Manuel Ramírez, and Luis Miguel Hernández. 2021. "Co-Inocula Assays of Yeasts with “Killer” Pheno-Type and Sensitive Strains of Saccharomyces cere-visiae with Defects in Mannoprotein Synthesis" Proceedings 70, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods_2020-07732

APA StyleGil, P., Martínez, A., Bautista, J., Velázquez, R., Ramírez, M., & Hernández, L. M. (2021). Co-Inocula Assays of Yeasts with “Killer” Pheno-Type and Sensitive Strains of Saccharomyces cere-visiae with Defects in Mannoprotein Synthesis. Proceedings, 70(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods_2020-07732