1. Introduction

Air traffic control is a very demanding task where one or several Air-Traffic Controllers (ATCos) plan, send, and execute commands via voice communications, in order to ensure the safety of the airplanes in a given space area. This article explains how ATCOis using speech-to-text systems and surveillance data to auto-transcribe ATC-related speech segments, i.e., voice communications between ATCos and pilots. This project aims to: (i) develop and implement a strong hardware/software pipeline for data collection of ATC segments with very high frequency receivers and (ii) explore and implement current state-of-the-art techniques for automatic speech recognition and call sign detection, which can lead to the development of new ATC systems to reduce ATCos’ workload and increase safety in ATC management.

ATC communication currently relies on two approaches, voice communication and voiceless communication through data links (also called CPDLCsystems). One example of a CPDLC system is the Eurocontrol Link200+ [

1], which was expected to be deployed in all European airports by 2016. The idea is to transfer certain commands and orders through a human-machine interface, thus reducing the amount of spoken communication, but increasing the ATCos’ workload. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) stated that “To minimize pilot head down time and potential distractions during critical phases of flight, the controller should use voice to communicate with aircraft operating below 10,000 ft above ground level”; hence, voice communications remains as the main way to exchange information and commands near airports. Recent research projects [

2] and the ICAO have stated that air-traffic is expected to grow between three and six percent yearly at least until 2025. The European Union (EU) with the aim of decreasing the ATCos’ workload has invested resources into projects such as MALORCA (MAchine Learning Of speech Recognition models for Controller Assistance, website:

http://www.malorca-project.de/wp), AcListant (AcListant homepage:

www.AcListant.de), and ATCO

, which have demonstrated detailed results on reducing the ATCos’ workload [

3], increasing the efficiency [

4], and even offering better solutions in integrating contextual information, also in real time [

5].

In [

6], the authors showed for the first time that including context knowledge in Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) systems significantly reduces Word Error Rates (WER) in an ATC task. For instance, the WER was reduced by a factor of almost 10 times i.e., 2.8% to 0.3%. This improvement is mostly due to an improved call sign recognition. In a follow-up project, AcListant and DLR focused on integrating the Universität des Saarlandes (USAAR) speech recognizer into their arrival manager (in order to improve the prediction of the landing sequence); while USAAR extended the features of its context integrating the speech recognizer in the Düsseldorf approach. Later works showed that in ideal conditions, it is possible to obtain 95 to 97% Call Sign Detection (CSD) rates when matching a transcribed utterance (output from an ASR engine) with a list of possible call signs (either from radar or the OpenSky Network server) in a given sector.

In fact, this was shown in MALORCA, where timestamped radar data are extracted for a given area and matched with a given utterance. However, to achieve these performances, the speech data have to be clean, and the target airport location needs to be well represented during the training of the speech-to-text recognition system [

3,

4]. In MALORCA, the radar data and speech data are provided directly by Air-Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs), which in most of the cases, is legally and technically complicated process. Moreover, such data are not usually sufficient for building a robust model due to the lack of generalization across different airports/countries and accents.

1.1. Motivation

ATCO

aims to collect huge amounts of data to build a robust ASR system for ATC that will generalize across different airports, speakers, and accents. The large non-transcribed audio database will be gathered with VHF (Very High Frequency) receivers owned by a community of volunteers. At this moment, the ATCO

consortium is finishing the development of the receiver software, and three different hardware setups are considered to be located in different regions in Europe (at the moment, Prague, Czechia, and Zurich and Sion, Switzerland). Meanwhile, spoken ATC communications from

LiveATC.net were collected and transcribed; LiveATC uses similar VHF receivers as the ones that are intended for use. Currently, the call sign detection performance is approximately six times worse than what MALORCA has demonstrated [

7,

8] (although the contextual information is so far avoided). We attribute this to the low (signal-to-noise) ratio of the collected speech segments. Nonetheless, we propose two ways to improve the performance: (i) either using more expensive equipment (receiver and/or antenna); or (ii) employing air surveillance data from the OpenSky Network (OSN) as contextual information in our recognizer. Despite the low quality of the recordings, we aim to rely on OSN servers to correlate a given speech data segment with air-surveillance data, which will improve the call sign detection system.

As mentioned in

Section 1, one of the current limitations in developing highly accurate speech-to-text systems and call sign detection systems for ATCo communications is the lack of annotated data. Normally, between eight and ten man-hours of effort [

9] (mainly because it requires highly trained participants, often active or retired ATCos) are required to annotate one hour of raw ATCo-pilot voice communication. Afterwards, nearly ten to fifteen minutes of ATCos voice activity are obtained after silence removal; hence, approximately one man-week of work is required to get an hour of ATCos without silence [

9,

10]. Therefore, it is of great interest to develop a robust speech-to-text and speech-to-call sign system that is aided by context information (air-surveillance data), capable of recognize spoken call signs independently of the accent, airport, or ATCo’s origin.

2. Methods and Materials

What can we do with surveillance data? Currently, we focus on CSD as this is the most valuable information we can extract. The surveillance data can be plugged into the ASR decoder to re-rank the generated word recognition hypotheses and then select the one that matches the call sign extracted from the surveillance data. At the same time, we should be aware that not all airplanes are equipped with ADS-B transponders; hence, smaller planes might not be present in the surveillance data, i.e., this is not a binary problem, but instead, we will leverage the retrieved call sign list from OSN servers to increase the chances of spotting the right call sign.

Retrieving surveillance data from the OpenSky Network: The recorded ATC utterances are stored together with a timestamp. This timestamp can be used in combination with the receiver (or airport) location to send a query to the OpenSky Network (OSN) database. The OSN collects ADS-B and Mode S data from airplanes from many locations around the world. The query to the database has two parameters: the time range and the search area. The time range is centered on the timestamp, and the search area is centered on the receiver (or airport) location. The query returns the ADS-B information from every plane that matches the criteria. The call signs contained in the ADS-B information are present in the ICAO format, which is a three-character airline code, e.g., LUF(Lufthansa), followed by the call sign number, which consists of a digit combination and may also contain an additional character combination, e.g., LUF189AF. This is the compressed form of a call sign.

Verbalizing the compressed call sign: In ATC communications, this compressed form is “spoken out” by using three different rules. The ICAO code is substituted by the airline call sign (LUF → LUFTHANSA). The digits are read out one by one (in some cases, there are deviations), and the characters are spelled out with the aid of the ICAO alphabet for radiotelephony:

| LUF189AF → LUFTHANSA ONE EIGHT NINE ALFA FOXTROT |

Nevertheless, some other non-standard abbreviations can exist in the data. Another relatively frequent deviation from the standard is shortening the airline code-word, if the current ATC situation is not ambiguous:

| LUFTHANSA → HANSA |

| SCANDINAVIAN → SCAN |

| SCANWING → SCAN |

| TRANSAVIA → AVIA |

| RYANAIR → RYAN |

| SPEEDBIRD → BIRD |

The initial contact should always be with the full call sign, and later, the ATCo may start using the abbreviated version. Taking these variations into account improves the chances of matching the form used in the actual utterance.

Automatic Speech Recognition system (ASR): This is an important module for detecting the call sign. Briefly, it automatically generates a text from the incoming audio signal. The output can be either the best transcript or a graph encoding alternative hypotheses. Inevitably, the output contains some errors, and narrowing down the search space (employing a list of possible call signs in a given space area retrieved from OSN servers) can improve the word error rate and also improve the call sign detection.

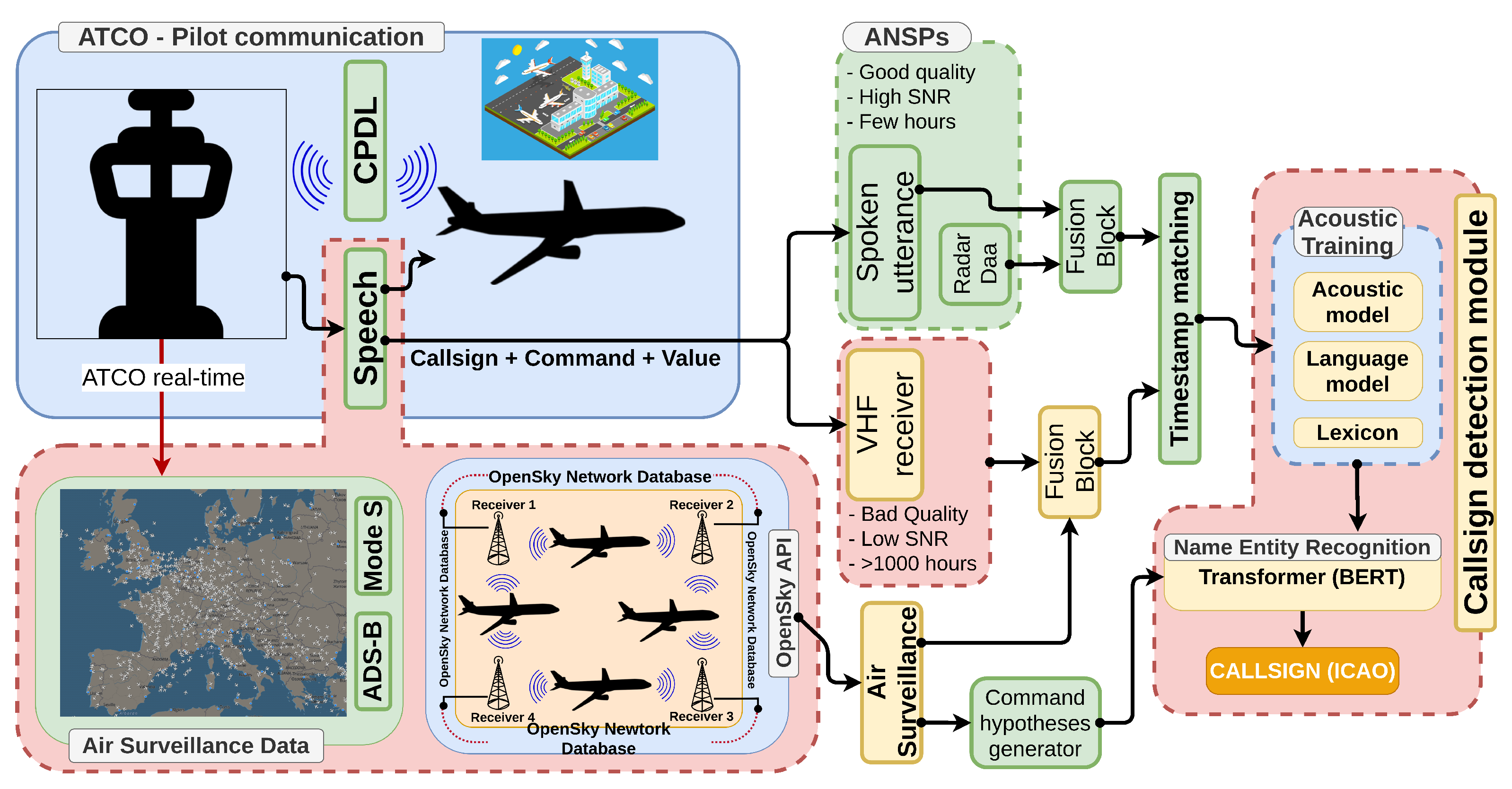

Proposed pipeline: ATCO

proposes a platform that will be able to retrieve the call sign from a given utterance, timestamp, and location, as summarized in

Figure 1. Initially, a speech utterance is recorded and timestamped with a VHF receiver; then, a query to the OSN server is sent to retrieve the call signs in that area and at that given time. Afterwards, a fusion block matches either the pilot or ATCo speech segment (after voice activity detection and diarization) with the surveillance data retrieved from OSN servers; moreover, in parallel, several commands are spawned from the command hypotheses’ generator, which will help to narrow the search space and also will be used as a context in the last block (at the moment, this functionality has not been tested yet). Finally, the last block is represented by a Named Entity Recognition (NER) model based on a transformer (BERT [

11]) for the final call sign extraction.

3. Speech Recognition, in More Detail

Currently, there are two main paradigms for speech recognition:

(a) A hybrid system with a separate acoustic model, pronunciation lexicon, and language model: The scores from these models are “glued” together by the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) to generate hypothesized text from the time series of the input speech signal. It is an older paradigm, which is on one side more complicated, but which allows training the acoustic model and language separately in parallel. For the “hybrid” system, we can collect or even synthesize the text data and pronunciation of new words in advance, hoping that it will match the target domain of the recognizer. If a word is missing from the lexicon, it cannot be produced in the recognizer output; thus, we have to “know” all the words in advance.

(b) An end-to-end system (also called a “sequence-to-sequence” or “encoder-decoder” system): Here, a sequence of input features (extracted from the speech signal) is transformed by a neural network to produce a sequence of output symbols (typically sub-word units). Internally, the input features are first encoded to a higher dimensional space of an “embedding” by the encoder neural network. Then, the decoder neural network classifies these “intermediate features” into a sequence of sub-word units (typically “byte pair encoding” units). The “end-to-end” systems learn mostly from the audio data and their transcripts. Using extra “text” data can be done with a shallow fusion (weighted AM+LM) between the acoustic system and a language model trained on the text data. If a word was not present in the training data, it still might be okay as long as it can be composed from the sub-word units.

4. Call Sign Detection Module

The Named Entity Recognition (NER) in the call sign detection module (

Figure 1) is a sequence labeling task. The named entity of interest is the call sign in the transcript. Since the call sign is a part of an ATC command, which specifically addresses an individual plane, it is crucial to detect it correctly to identify the target plane. For the labeling, the IOB format is used, which stands for Inside, Outside, and Beginning. This results in the labels B-CALL, I-CALL, and O. The label B-CALL marks the beginning of the call sign in the transcript, while I-CALL labels are used for words of the call sign that are inside the named entity. All words that are outside of a call sign are marked with the O tag. The correct labeling of the transcript below:

| “K-L-M Two Seven Yankee call Amsterdam on one three four decimal three seven five” |

Will therefore look as follows:

| “B-CALL I-CALL I-CALL I-CALL I-CALL I-CALL O O O O O O O O” |

The task of the NER module is to produce the correct label for each word in the transcript. Based on the labels, the call sign (“KLM Two Seven Yankee”) can be isolated from the transcript. The module itself is based on a transformer [

12]. In contrast to classical RNN architectures, like Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs), the transformer architecture is highly parallelized and therefore allows faster training on GPUs. In addition, there exist transformer models that are pre-trained on big text corpora and only require being fine-tuned on the specific task. Fine-tuning for our NER task means supervised training on labeled transcripts. In this work, we use BERT, a pre-trained bidirectional encoder for the labeling task [

11].

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Building Our Speech Recognizer

In this section, we work with a “hybrid” speech recognizer. This is an HMM based recognizer with the TDNN-F[

13] acoustic model trained by the lattice-free MMIobjective [

14]. We use the n-gram language model and the Librispeech [

15] lexicon, which we extend with Phonetisaurus G2P [

16] to get the pronunciations of new words (e.g., “Lufthansa”).

The speech recognition acoustic model was trained on 195 hours, which comprised of seven training databases, as shown in

Table 1. This dataset was additionally augmented by adding noises that matched the LiveATC audio channel, which doubled the size of the training data.

What turned out to be a difficult task was unifying the transcripts of these datasets:

use the same ICAO alphabet and “number words”

standardize the word-splitting: use “take off” “take-off’,’ or “takeoff”?

ligature the multi-word airline designators in call signs: “air berlin” → “air_berlin”

We also enriched the language model and lexicon with:

the list of airline designators for call signs (partly manually updated):

all “verbalized” call signs from the OpenSky Network flight list 2019/2020 collection:

all possible runway numbers (verbalized)

and all waypoints in Europe that we dumped from the project Traffic:

For testing, we had existing test sets from the AIRBUS (our selection for the held-out set) and MALORCA (Vienna training/test set) databases. In addition, we collected our own test sets, either by downloading public data (LiveATC) or by recording the data (LKTB) with a better device and antenna than LiveATC is currently using. The data were manually transcribed by a group of volunteers.

In

Table 2, we see that the WER is reasonably low for AIRBUS and MALORCA (<10%). On the other hand, our own collection from LiveATC has much worse WER of around 34%, while our own collection from the LKTB airport is roughly half-way, at 24.7% WER. This performance gap is caused by two factors. First, the LiveATC data are noisier than the AIRBUS, MALORCA, or LKTB data. This also increases the error rate despite the noise augmentation we already used on the training data. Second, the LiveATC and LKTB data come mainly from different airports than those that are present in the training data for the ASR system. Thus, some lexical elements are different: call signs, waypoints, runways, and local names. Similarly, the speakers and their accents can be different. This “new airport” gap can be seen by comparing LKTB with AIRBUS or MALORCA. Part of this gap can be compensated by boosting a carefully selected list of words completed with a list of call signs from surveillance data.

5.2. Boosting the Call Signs in Speech Recognition

If we know in advance which call signs are likely to be said, we can take advantage of that and “suggest” that the recognizer produce them in its output. It is important to recall that in a “hybrid” speech recognition system, there are two principal ways of using the “list of possible call signs”:

(a) A priori: The speech recognizer uses the HCLG recognition network. This represents the search space in which the recognizer operates. In this search graph, we can give score discounts to certain words or even phrases. This increases the chance that the correct call sign appears in the recognized text or in the “lattice” of alternative hypotheses.

(b) Ex-post: This is done after the recognizer has created “lattices” of alternative hypotheses. The positive part is that operating with lattices is less computationally intensive than decoding. On the other hand, there is no way we can detect the correct call sign if its word-sequence is not present in the lattice.

For now, let us focus on a priori boosting, as it has higher potential to improve the detection of call signs in the audio at an earlier stage. As mentioned before, the decoder explores the paths that exist in the HCLG graph. The score discounts can be given by creating a boosting graph B, which is right-composed with HCLG as . The boosting graph B has to accept any word sequence generated from HCLG, plus it contains a sub-graph obtained from a list of boosted phrases. After a few initial experiments, we decided to give a score discount −1.0 to every word in the boosted phrase; plus, the first word got a tunable additional discount to better anchor the phrase during the decoding.

So far, we have applied this to “LiveATC Set 1” and “LiveATC Set 2”. We boosted the recognition network HCLG once per test set, which is rather non-specific. Nevertheless, we already obtained some WER improvement (

Table 3), which tells us that we are on the right path.

The next step is to try to use boosting with the call sign list coming from a shorter “time window”. If that were done with , it would require many compositions (one composition takes 5 min, and it requires >1 GB of RAM and about 100 MB of disk space). Therefore, either we need to find a faster way to boost the recognition network, or we will have to start using the ex-post boosting on the lattices.

5.3. Call Sign Identification

The NER module was trained on the first 20,000 samples of the training data of the AIRBUS dataset. Testing was done with the best performing model after 10 epochs training. The model was tested on two different test sets. The first test set consisted of the last 4000 samples of the training data of the AIRBUS dataset (these samples were not used during training) and on the whole LiveATC Set 1. The results are shown in

Table 4.

The F1 score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall and is a measurement of the accuracy reached on the datasets. The F1 score ranges from zero to the highest possible value of one, representing maximum accuracy. The precision value measures how many of the call signs’ labeled sequences are actual call signs. For the call sign identification, recall is more important than precision, because it is a measure for how many call signs are actually identified as such. In other words, a low recall means that some call signs are not identified at all, and the corresponding command cannot be assigned to a plane. The results show that the model performs better on the AIRBUS dataset, which is due to the fact that the transcript of this dataset contains mainly full call signs. Because of the noisy LiveATC data, parts of the call signs are often not understood and therefore missing in the transcript. Because the model is trained on mainly full-length call signs, the recall value on the LiveATC Set 1 drops significantly. To overcome this problem, we are working on feeding relevant call signs from the OSN database as additional input for the model.

6. Conclusions

This article introduces ATCO and its main objectives such as speech-to-text and call sign detection for air-traffic spoken communications; where we show that speech recognition can be done on ATC communications gathered through VHF receivers. Additionally, we compare the two most common methods for building speech recognizers currently, which are hybrid and end-to-end based systems. If it is clear that the hybrid systems outperform the proposed end-to-end approach, we believe that end-to-end systems bring different advantages, which can be further exploited in the future. Our method of boosting the speech-to-text system with call signs retrieved from the OpenSky Network was tested successfully; still, further research to increase the speed of the boosting and narrowing it to less “utterances” or even boosting per-utterance is needed. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study employing seven air-traffic command-related databases spanning more than 195 h of speech data that are strongly related in both phraseology and structure to ATCo-pilot communications. Further, a huge work on the standardization and normalization of these seven databases was done; which helped to accomplish the proposed goals. We showed that our speech recognition models are able to generalize across ATC spoken communications from different countries, English accents, airports, and speakers. In fact, we achieved competitive results in both of our crafted test sets from LiveATC when performing a boosting with a list of call signs retrieved from OSN servers; for Test Sets 1 and 2, we achieved, respectively, 33.6% and 30.8% WER. Finally, our call sign detection module based on transformers yielded 0.95 and 0.73 for the F1 scores for Airbusand LiveATC Test Set 1, respectively.