Abstract

Some ethical evaluation models for Intelligent Assistive Technologies (IATs) have been presented in the literature. However, it has been proven that the vast majority of IATs were designed in the absence of explicit ethical values and considerations. In order to shed light on this problem, this paper presents a review of the literature on ethical values and considerations regarding IATs. According to this review, four challenges are identified to facilitate the evaluation of ethical models in IAT design: (i) Rational method, (ii) uncertainty evaluation process, (iii) evaluation results and aggregation process, (iv) software tool. These challenges are analyzed in order to propose an initial ethical model based on linguistic decision analysis.

1. Introduction

Expanding life expectancy provides an important opportunity for ageing people, their families, and society. With the continued growth of an ageing population, society faces new challenges, including the development of biomedical, physical, psychological, and socio-environmental intervention environments and services for older people to promote active ageing and wellbeing [1].

Smart environments with sensors and actuators for Ambient, Active, and Assisted Living (A3L) are an excellent tool to provide services that: (i) Improve the quality of life of elderly people, (ii) cover their social and health needs, (iii) help families to achieve a true balance between personal and working life, and (iv) improve the workload and physical and cognitive burden on caretakers or care giving services in general [2].

Intelligent Assistive Technologies (IATs) have been proposed to enhance the autonomy of ageing people with regards to daily dependency problems. Some of these technologies are described below:

- An infrastructure for supporting the needs of elderly people through simple interactions with the environment from an augmented-reality perspective was proposed in [3]. A general and adaptive model to transform the physical information of objects in the environment into a virtual representation through accelerometers and digital compasses was presented;

- An intelligent medication system to monitor medication intake was proposed in [4], which analyzes body temperature data streams provided by a wearable device in order to dispense medication using a low-cost remote dispenser installed at home. The main innovation was a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis based on a fuzzy linguistic approach and fuzzy logic. This analysis provided accuracy and adherence to patient fever in the decision making of medication intakes, adjusting the doses and waiting times based on previous intakes;

- An unobtrusive computer vision-based method for continuously monitoring the gait velocity of people within their own home was proposed in [5]. Gait velocity is a valid, reliable, sensitive measure that is appropriate for assessing and monitoring functional status and overall health [6]. This system provides advantages to make interventions potentially faster and more effective due to the fact that detecting changes in gait velocity can aid in providing interventions to prevent hospitalization. Gait velocity is currently assessed in a clinical setting where the patient is timed by a clinician over a measured distance of 3–6 m.

At the same time, several ethical evaluation models have been presented to evaluate IATs [7,8,9,10]. However, the vast majority of IATs are designed in the absence of explicit ethical values and considerations [11].

There is a need to review the proposed ethical models to identify new challenges in order to define a new flexible ethical evaluation model to facilitate its generalization and use in the design of IATs. In this paper, an ethical review of values and considerations regarding IATs is presented. Following this, four challenges are proposed and analyzed. Finally, an initial flexible ethical evaluation model based on decision analysis is proposed to facilitate the ethical evaluation of IATs.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents an ethical review of values and considerations in IAT. Section 3 proposes and analyzes four challenges in the ethical evaluation process of IATs. Section 4 presents an initial flexible ethical evaluation model for IATs, considering these challenges. Section 5 provides concluding remarks, discussing the limitations of this research, and proposed future research.

2. Review of Ethical Values and Considerations in IAT

Intelligence is a complex construct. According to Howard Gardner, intelligence is not a unitary set that groups together different specific capacities, but is like a network of autonomous sets related to each other (understanding intelligence as a multidimensional construct). This set of related autonomous elements is included in the design of the architecture of sensors and intelligent devices for the A3L of older adults. The objective is for the intelligent design of IATs to be applied to improve quality of life during the ageing process, with an emphasis on human and ethical aspects and dignity.

Several models have been proposed in the literature to structure the design of intelligent devices and sensors under the perspective of ethics in IATs. Some of the most relevant ones are reviewed below:

- The Ageing Lab Foundation [7] proposed the Dignified and Positive Ageing Model (hereinafter, DPA). This biopsychosocial intervention model is based on a multidisciplinary approach to intervention with older adults, which is supported on a double perspective where dignity and positive ageing are the key elements: Dignity, understood as full respect for the person, whatever his or her situation, and Positivity, approaching ageing from an optimal, active, and participatory perspective regarding physical, psychological, and social welfare.DPA refers to a working concept and a way of operating that characterizes a society based on how it serves people and which focuses on the “how” to age. Likewise, within the DPA model, ageing is understood as a challenge for society but not as a burden. This intervention model stems from a working philosophy based on commitment to society, motivation, and continuous improvement, and aims not only to consolidate a methodology for the service, but also to value a philosophy of care involving multiple parties. This model proposes the following five principles: Bioethics, active participation, well-being, collaborative intelligence, and co-responsibility. The DPA model considers different criteria associated with each of the principles mentioned (see Table 1), which guide the specific actions for interventions.

Table 1. Principles and criteria in the Dignified and Positive Ageing (DPA) model.

Table 1. Principles and criteria in the Dignified and Positive Ageing (DPA) model.

- 2.

- Floridi and others propose the following as unified ethical principles for artificial intelligence (AI): Nonmaleficence, beneficence, autonomy, and justice, adding the specific principle of explainability [8] (see Table 2). This model could also be transferred to the design of intelligent tools and devices, updating the initial concept and adapting the conceptual basis.

Table 2. Evaluation model proposed by Floridi and others.

Table 2. Evaluation model proposed by Floridi and others.

- 3.

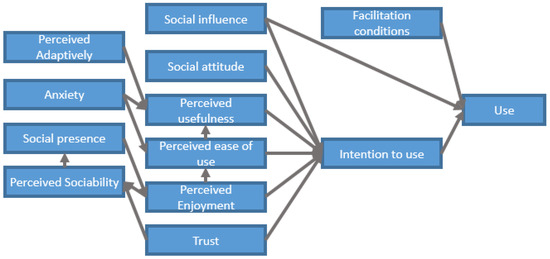

- Heerink et al., in the Almere Model [9], propose an assessment of the acceptance of assistive technology by older adults (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evaluation model proposed by Heerink and others.The research develops and tests a theoretical adaptation and extension of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) explaining the intention to be used not only in terms of variables related to functional evaluation, but perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Based on the data of the study conducted in the city of Almere, it concludes that the conditioning factors of attitudes, gender, age, technological knowledge, etc., are perceived positively in order to integrate advanced technological systems in environments where older people live;

Figure 1. Evaluation model proposed by Heerink and others.The research develops and tests a theoretical adaptation and extension of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) explaining the intention to be used not only in terms of variables related to functional evaluation, but perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Based on the data of the study conducted in the city of Almere, it concludes that the conditioning factors of attitudes, gender, age, technological knowledge, etc., are perceived positively in order to integrate advanced technological systems in environments where older people live; - 4.

- Robillard et al. propose the concept of “ethical adoption”: The deep integration of ethical principles in the design, development, deployment, and use of technology. Ethical adoption is based on five pillars, supported by empirical evidence: (1) Inclusive participatory design; (2) emotional alignment; (3) adoption models; (4) evaluation of ethical standards; and (5) education and training. To close the gap between adoption research, ethics, and practice, a set of 18 practical recommendations based on these ethical adoption pillars was proposed [10] (see Table 3).

Table 3. Ethical adoption in the context of dementia.

Table 3. Ethical adoption in the context of dementia.

There are other institutional and academic research and papers advising on ethics and technology for human assistance, such as:

- European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (EGE). An independent, multidisciplinary body advising on all aspects of the Commission’s policies where ethical, social, and fundamental rights issues intersect with the development of science and new technologies [12];

- IEEE’s Global Initiative for the Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems. The new standards projects are the latest additions to the IEEE P7000 family of standards™, which supports the IEEE’s primary objective of prioritizing ethical concerns and human well-being in the development of standards that address all aspects of autonomous and intelligent technologies [13];

- The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), one of the guiding principles which states: “Respect for inherent dignity, individual autonomy, including the freedom to make one’s own choices, and the independence of people” [14]. The proposed principles should be taken into account for the design of environments with intelligent devices.

3. Challenges to an Ethical Evaluation Model for IATs

Once the state of the art has been reviewed, in this section we identify the following four challenges and propose tools to address them.

3.1. Rational Evaluation Methodology

Currently, the proposed ethical models are based on providing only a set of criteria or guidelines to be taken into account. In addition, these proposed models converge on the fact that evaluation should be multidisciplinary and taken on by different actors [15]. However, there is a lack of rational ethical evaluation methodologies to carry out this process.

Therefore, it is a challenge to provide an ethical evaluation methodology that defines the evaluation framework. In this sense, we propose the use of decision analysis methods that provide a rational analysis in a simple and quick manner in order to obtain a global assessment. Decision analysis [16] has been successfully applied to evaluation processes, such as the appraisal model [17]. A classical decision analysis scheme consists of the following phases [18]:

- Problem: The decision, objectives, and alternatives of the problem are identified;

- Framework: The structure of the problem and the expression domains in which the assessments can be made are defined;

- Gathering information: The decision makers provide their information;

- Computing results: A collective assessment for each alternative is obtained;

- Ranking: The alternatives are sorted according to the results obtained, establishing a ranked list;

- Making a decision.

The application of the decision analysis scheme to an ethical evaluation process does not necessarily involve all these phases. The phases that could be considered essential for an evaluation problem are: Establishing the framework, gathering information, and rating the alternatives.

3.2. Uncertainty Evaluation Process

The evaluation process in the design of IATs presents uncertainty due to the fact that it operates with vague and imprecise information. In the proposed models, the set of criteria are evaluated in a quantitative way by multiple parties, usually providing numerical assessments. This entails a lack of accuracy in the ethical evaluation model due to the difficulty of expressing qualitative criteria and subjective judgments quantitatively in a precise way, providing numerical results. For this reason, the use of numerical values to represent such uncertain information is not adequate because the uncertainty is not of a probabilistic nature.

Therefore, it is a challenge to propose a flexible framework in which multidisciplinary evaluators can provide their assessments in a linguistic domain, according to the uncertainty and nature of the criteria and the background of each evaluator.

In this context, we propose a linguistic evaluation framework according to the fuzzy linguistic approach. This approach has provided excellent results for modeling uncertainty in information of a non-probabilistic nature [19,20,21,22].

3.3. Evaluation Results and Aggregation Process

The results generated by the ethical models provide numerical or Boolean results, which are difficult to understand and interpret. Therefore, there is a new challenge in providing linguistic results that are understandable and interpretable. Furthermore, the ethical evaluation of an IAT is based on a hierarchy of criteria and the set of assessments provided by multiple actors; a related challenge is to express intermediate ethical considerations linguistically, considering each sub criteria and each party involved.

In this context, the linguistic results as well as the computing with words (CWW) paradigm emulate human cognitive processes to make reasoning processes and decisions in environments of uncertainty and imprecision [19]. In this paper, we propose the computing with words paradigm, using the 2-tuple linguistic representation model for its accuracy, its usefulness for improving linguistic problem-solving processes in different applications, its interpretability or its ease in managing complex frameworks in which linguistic information is included [23].

3.4. Software Tool

Even though there are many ethical models, there is a lack of software tools to evaluate IATs, according to each proposed model. This is a prominent problem that causes IAT designs not to be evaluated. Therefore, it is a challenge to provide a flexible software tool that allows the ethical evaluation of an IAT, considering a hierarchy of criteria as well as the multiple parties involved under a linguistic evaluation framework.

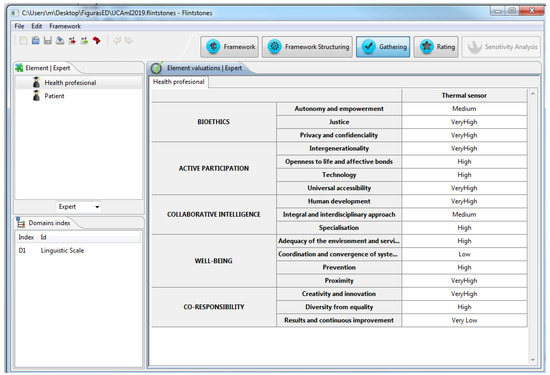

In this context and considering the challenges previously analyzed, we propose the use of Flintstones [23] to manage the ethical evaluation process. Flintstones is a Fuzzy LINguisTic deciSion TOols enhaNcEment Suite, developing a linguistic decision analysis following the computing with words paradigm with the 2-tuple linguistic model [23].

4. Flexible Ethical Evaluation Model for IATs

This section presents a flexible ethical evaluation model for IATs by using Flintstones, which manages the uncertainty involved in the perceptions of the evaluator using the 2-tuple linguistic representation model. Furthermore, the model provides linguistic results in order to offer interpretable and understandable results for the evaluation process. The flexible ethical evaluation model consists of the following phases:

- Evaluation framework. This framework defines the structure of the ethical evaluation model. It includes the set of evaluators, the set of criteria that will be evaluated, and, finally, the linguistic scale on which evaluators’ perceptions will be expressed. Therefore, the theoretical framework includes the following elements:

- 1.1.

- Evaluators. The set of evaluators is defined by . This set of evaluators provides their perceptions of the IAT. The set of evaluators is composed of subsets of evaluators that interact with the IATs of patients, relatives, caregivers, healthcare professionals, etc.;

- 1.2.

- Hierarchy of criteria. This hierarchy is evaluated by the evaluators according to the nature of the IAT. The first level set of criteria is defined as , where multiple sub-criteria may be involved in each criterion, defined as ;

- 1.3.

- Linguistic scale. To define this scale, it is necessary to set its number of terms, syntax, and distribution. The semantics for each linguistic term are represented by the linguistic 2-tuple representation model. An example of linguistic scale is defined by ;

- 2.

- Gathering information. Once the framework has been defined to evaluate an IAT, the information must be provided by the set of evaluators. Each evaluator provides its perception of each criterion included in the hierarchy, using a linguistic scale term. Therefore, . It should be noted that not all evaluators will have the knowledge to provide their assessments on each criterion. Therefore, when the evaluator is not relevant, the assessment will be Not Applicable, defined by ;

- 3.

- Computing ethics results. This phase computes a collective assessment for each criterion in order to compute a global assessment of the IAT, according to the perceptions of the evaluators. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out CWW processes for linguistic terms by using linguistic aggregation operators for 2-tuple linguistic values. Different aggregation operators have been proposed for linguistic 2-tuples [15]. This phase includes the following three steps:

- 3.1.

- Computing global ethical sub-criteria values, . In the first step, the assessments of a given evaluator for each sub-criterion are aggregated by means of a 2-tuple linguistic aggregation operator to obtain a global value for each sub-criterion;

- 3.2.

- Computing global ethical criteria values, . In the second step, global sub-criteria assessments for each criterion are aggregated by means of a selected 2-tuple linguistic operator to obtain a global value for each criterion;

- 3.3.

- Computing global ethical values, . In this third step, the global value for the IAT is computed, aggregating the global criteria values by means of a selected 2-tuple linguistic operator.

Figure 2 illustrates how the model can be implemented in the Flintstones tool.

Figure 2.

Gathering information with Fuzzy LINguisTic deciSion TOols enhaNcEment Suite (Flintstones).

5. Conclusions and Future Research

This paper presents a review of the literature on ethical values and considerations regarding IATs. According to this review, four challenges have been identified to facilitate the evaluation of ethical models in IAT design. Considering the four challenges, an initial ethical evaluation model based on decision analysis has been proposed to provide a rational evaluation method. Furthermore, the proposed model provides a linguistic evaluation framework to correctly model the uncertainty in this evaluation process. Computing with words processes are carried out in the proposed model to provide interpretable and understandable results by means of a 2-tuple linguistic model and its software tool.

In future research, we will study how to provide a heterogeneous framework in which evaluators can provide their assessments within different domains, according to the uncertainty and nature of such criteria and the background of each reviewer. Moreover, with the aim of ensuring the effective aggregation of the information, we shall address the challenge of researching the most suitable aggregation operators to cope with the interaction among criteria and evaluators and their weighting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E. and J.M.; methodology, M.E. and J.M.; software, M.E.; formal analysis, M.A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E. and J.M.; writing—review & editing, all authors.

Funding

This research was funded by REMIND project Marie Sklodowska-Curie EU Framework for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020, under Grant Agreement No. 734355, the Spanish government by means of the projects RTI2018-098979-A-I00 and CAS17/00292 and Andalusian Region with PI-0203-2016 and PI-0387-2018.

Acknowledgments

F. J. Estrella for the development of the first version of FLINTSTONES that has been used in this research and Anara Perandrés for her review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vazquez, M.; Sexto, C.; Rocha, A.; Aguilera, A. Mobile Phones and Psychosocial Therapies with Vulnerable People: A First State of the Art. J. Med Syst. 2016, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinilla, M.; Martínez, L.; Medina, J.; Nugent, C. The Experience of Developing the UJAmI Smart Lab. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 34631–34642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervás, R.; Garcia-Lillo, A.; Bravo, J. Mobile Augmented Reality Based on the Semantic Web Applied to Ambient Assisted Living. In Ambient Assisted Living. IWAAL 2011; Bravo, J., Hervás, R., Villarreal, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6693. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, J.; Espinilla, M.; García-Fernández, Á.L. Intelligent multi-dose medication controller for fever: From wearable devices to remote dispensers. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 65, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Quero, J.; Shewell, C.; Cleland, I.; Rafferty, J.; Nugent, C.; Estévez, M.E. Computer Vision-Based Gait Velocity from Non-Obtrusive Thermal Vision Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops), Athens, Greece, 19–23 March 2018; pp. 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, A.; Fritz, S.L.; Lusardi, M. Walking speed: The functional vital sign. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Cruz, A. Cuaderno O. Cuidados, Modelo EDP. Envejecimiento Digno y Positivo; Fundación Ageing Lab: Jaén, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Luciano, F.; Cowls, J.; Beltrametti, M.; Chatila, R.; Chazerand, P.; Dignum, V.; Luetge, C. AI4People—An Ethical Framework for a Good AI Society: Opportunities, Risks, Principles, and Recommendations. Minds Mach. 2018, 28, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerink, M.; Kröse, B.; Evers, V. y col. Assessing Acceptance of Assistive Social Agent Technology by Older Adults: The Almere Model. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2010, 2, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, J.M.; Cleland, I.; Hoey, J.; Nugent, C.D. Ethical adoption: A new imperative in the development of technology for dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ienca, M.; Wangmo, T.; Jotterand, F.; Kressig, R.W.; Elger, B. Ethical design of intelligent assistive technologies for dementia: A descriptive review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2018, 24, 1035–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, Á.; García-Mayor, R. Ethical challenges posed by the use of Artificial Intelligence in the diagnosis and clinical treatment. Asociación Española de Bioética y Ética Médica. Cuadernos de Bioética 2018, 29, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IEEE Global Initiative and EAD. ETHICALLY ALIGNED DESIGN. A Vision for Prioritizing Human Wellbeing with Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems. Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/content/dam/ieee-standards/standards/web/documents/other/ead_v1.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Principios Rectores de la Convención de los derechos y la dignidad de las personas con discapacidad de la ONU. Available online: https://www.un.org/spanish/disabilities/default.asp?navid=15&pid=535 (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Shipunova, O.D.; Rabosh, V.A.; Soldatov, A.V.; Deniskov, A.V. Interactions design in technogenic information and communication environments. Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, R.L.; Raiffa, H. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Tradeoffs; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Espinilla, M.; de Andrés, R.; Martínez, F.J.; Martínez, L. A 360-degree performance appraisal model dealing with heterogeneous information and dependent criteria. Inf. Sci. 2013, 222, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemen, R.T. Making Hard Decisions. An Introduction to Decision Analisys; Duxbury Press: California, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, L.; Ruan, D.; Herrera, F. Computing with Words in Decision support Systems: An overview on Models and Applications. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. (IJCIS) 2010, 3, 382–395. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. The concept of a linguistic variable and its applications to approximate reasoning—I. Inf. Sci. 1975, 9, 199–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. The concept of a linguistic variable and its applications to approximate reasoning—II. Inf. Sci. 1975, 9, 301–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. The concept of a linguistic variable and its applications to approximate reasoning—III. Inf. Sci. 1975, 9, 43–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, F.J.; Espinilla, M.; Herrera, F.; Martínez, L. Flintstones: A fuzzy linguistic decision tools enhancement suite based on the 2-tuple linguistic model and extensions. Inf. Sci. 2014, 280, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).