Abstract

The dynamic economic development supported by progressive globalisation can be observed in every EU country. It would, therefore, seem that financial market instruments are not only known to, but also used by, the managers of SME’s (99% of all Polish businesses). It would seem that SME should all the more penetrate the financial market in search of thus far unseized subsidising opportunities. The article presents the results of the author’s own research concerning the respondents’ perception of capital market instruments, and defines the potential of companies with a legal status which enables them to establish cooperation with the key capital market institution in Poland (based on the responses of 400 persons representing various branches of entrepreneurship in the Wielkopolska region).

Keywords:

sources of financing; capital market; WSE; stock exchange; IPO; NewConnect; entrepreneurship 1. Introduction

A properly and effectively functioning capital market is one of the main economic pillars. It mobilises capital through the transformation of savings into investments, enables adequate capital allocation by properly defining financial needs and directing the flow of capital resources to economic sectors with a high investment capacity, and allows the valuation of capital and risk, market assessment of company value, as well as identification of threats associated with company operations. All this leads to greater transparency of business transactions, increasing their flexibility and innovation (see also: [1] (pp. 123–147).

The capital market concerns trading in securities, and the principal venue of such transactions is the stock market. In Poland it is the Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE) [2] (pp. 34–43). The stock exchange is a liquid tool that facilitates the matching of supply and demand, where excess capital ready to be invested meets entities seeking capital for investment (see also: [3] (pp. 281–307)).

The main division of the capital market is into primary and secondary market. The primary market deals with the issue of shares or other securities. The issue represents the first sale of shares, directly from their owner, who is referred to as the issuer [4] (pp. 1699–1726); [5] (pp. 281–307). We talk about the secondary market when it comes to sale-purchase transactions with investors who had already acquired shares. It is the most important segment as it reflects actual prices of securities and their value, which is affected by current market conditions (see also: [6] (pp. 1549–1563); [7] (pp. 11–24); [8]).

It is also important to understand the difference between raising capital for development on the public market and the non-public market. The issue of shares by a company is not, in fact, equivalent with listing them on the stock exchange. Only trading on the public market, which is ensured through an offer that reaches a wide audience of potential investors, who should have access to information concerning the company’s financial condition, allows an IPO on the WSE primary market and provides companies with fresh capital for further development [5] (pp. 281–307); [9] (pp. 1795–1828); [2] (pp. 34–43).

Hence, what is the potential of Polish entrepreneurs who, in accordance with the guidelines and rules of the stock exchange, have the status of joint-stock companies or limited joint-stock companies, which may seek to be listed? In this respect, the position of small and medium-sized entrepreneurs, who have always faced the so-called credit discrimination as defined in 1957 by J.K. Galbraith, is quite specific [10] (pp. 124–133) (see also: [11] (pp. 382–392); [12] (pp. 91–122); [13] (pp. 63–77)). The answer to these questions may, at least partly, determine the characteristics of a small and medium-sized Polish entrepreneur who, as in every national economy, by directly influencing macroeconomic factors, simultaneously affects the global development of economies around the world (see also: [10]; [14] (pp. 418–431)).

2. Materials and Methods

The purpose of the research is to identify effectiveness of the Warsaw Stock Exchange as a potential source of financing for small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as to analyse the number of joint-stock and limited joint-stock companies, whose legal form enables them to cooperate with the stock exchange, and the perception of capital market by SMEs as a potential source of capital for development [15] (pp. 91–105); [2] (pp. 34–543).

The results of the author’s own research are based on the responses of 400 persons representing various branches of entrepreneurship in the Wielkopolska region. In order to calculate and present the findings in tables and figures, mathematical analysis tools were employed, which enabled determining the relevant quantitative and percentage shares to illustrate the examined structures in the areas of interest and the dynamics of growth, as well as conducting a trend analysis based on linear regression methods.

Among professionally active respondents, 62% were women and 37% were men aged 18 to 65. 64% of them said that they had conducted business in the SME sector and 3.5% in large enterprises. 50% planned to start their own businesses in the following three years and 18.5% intended to engage in international trade.

3. Results and Discussion

Warsaw Stock Exchange is a leading financial instruments exchange in Central and Eastern Europe and one of the fastest growing stock exchanges in Europe. Its performance is all the more spectacular given that the Polish stock market is a financial institution with a relatively short history in comparison to the main players in this respect. The first listing took place in Warsaw on 16 April 1991, marking a political system transformation and a shift from a centrally managed to capital-based economy (see also: [15] (pp. 91–105); [2] (pp. 34–43)).

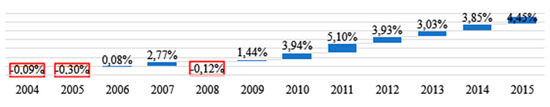

Since Poland’s accession to the European Union on 1 May 2004, the number of enterprises has increased by almost 17% (Data as at 31 December 2015). The highest growth rate as evidenced by the survival rate ≥5 years is demonstrated by small enterprises (According to the headcount classification: 0–9 employees—a microbusiness; 10–49—a small enterprise; 50–250—a medium-sized enterprise). The share of limited joint-stock companies was on a significant increase, with 4699 of such entities being active in Poland at the end of 2015. Nonetheless, higher growth dynamics can be observed among joint-stock companies—11,380 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Growth dynamics of joint-stock companies in Poland. Source: Own figure based on Central Statistical Office (GUS) data.

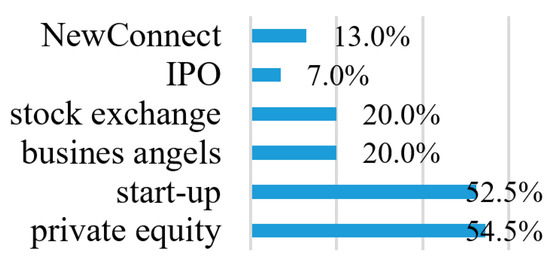

The question thus arises why so few entrepreneurs take up the opportunity to raise capital for development through the capital market and the offer of its fundamental institution, namely the stock exchange (see also: [16] (pp. 87–105)). The research findings have revealed that the fundamental reason is the lack of awareness and basic knowledge on economics and finance among SME owners, who do not distinguish between the money market and the capital market, as admitted by 60% of the respondents. Among alternative sources of funding, the notion of start-up is recognised and has been heard by 52.5%, with 3% of the respondents having even used this source (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Recognition of financial instruments among the respondents. Source: Own research.

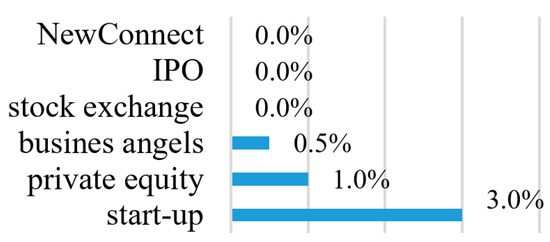

The term ‘private equity’ is the most commonly recognised, although it is less known to the respondents in practice (54.5% and 1%, respectively). The institution of ‘stock exchange’ as such can be correctly defined by only 20% of those surveyed, who also tend to recognise the NewConnect alternative trading platform, launched in 2007 and primarily intended for SMEs, more frequently than the primary market (IPO) (see also: [17] (pp. 249–265); [18] (pp. 619–654); [7] (pp. 11–24)). Nobody, however, considered this possibility of raising capital for development (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Use of alternative sources of financing by the respondents. Source: Own research.

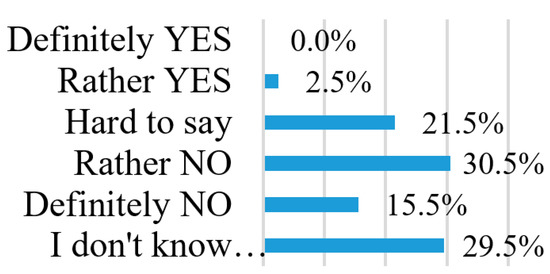

When asked about the stock exchange as a potential source of funding, without pointing to specific instruments, only 2.5% expressed the willingness to undertake such efforts (Figure 4). Nearly 30% of the respondents openly admitted that they did not know the opportunities offered by the stock exchange, but exactly half of them ruled out such a possibility, acknowledging that limited knowledge was a sufficient argument which triggered the psychological factor of fear of losing the money invested (see also: [19]; [9] (pp. 1795–1828)).

Figure 4.

Opportunities for raising capital for development through the stock exchange. Source: Own research.

4. Conclusions

Companies with a legal status authorising them to cooperate with the Warsaw Stock Exchange represent 0.4% of all companies operating in Poland. They are a potential target, in particular for NewConnect—an alternative trading platform dedicated to SMEs. The results of the author’s own research have revealed that such solutions are not known to the respondents, who potentially could raise funds through cooperation with the stock exchange. Both the primary market offer (IPO) and the very name of ‘alternative market’ are infrequently recognised. The respondents exclude the possibility of raising capital through cooperation with the capital market as they typically associate it with high risk and numerous formalities to complete. In the context of the questions asked, a worrying fact is the inability to differentiate between capital market instruments and the general confidence in the money market, the restrictiveness of which in relation to SMEs does not seem to raise any objections among SME owners. Could dissemination of knowledge possibly play a greater social role in this case than calculations and economic statistics? This topic should be explored in more depth and the answer to this question found because the social and sociological aspect and the development of social capital associated with trust in public institutions with the Treasury’s majority share in a country with a communist history which has experienced less than 30 years of free market, may be a fundamental determinant of SME development in Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Cassar, G.; Holmes, S. Capital Structure and Financing of SMEs: Australian Evidence. Account. Financ. 2003, 43, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, J. Regulation of the Warsaw Stock Exchange: History and Operating rules. J. Econ. World 2017, 5, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sarkar, J.; Sarkar, S.; Bhaumik, S.K. Does ownership always matter?—Evidence from the Indian banking industry. J. Comp. Econ. 1998, 26, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, B.A.; Kini, O. The post-issue operating performance of IPO firms. J. Financ. 1994, 49, 1699–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelson, W.H.; Partch, M.M.; Shah, K. Ownership and operating performance of companies that go public. J. Financ. Econ. 1997, 44, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X. Are publicly held firms less efficient? Evidence from the US property-liability insurance industry. J. Bank. Financ. 2010, 34, 1549–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, J. Alternative Securities Markets in Poland and the United Kingdom. Probl. Zarządzania 2016, 14, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, A.; Konidaris, T. SME Exchanges in Emerging Market Economies: A Stocktaking of Development Practices; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, J.R.; Welch, I. A Review of IPO Activity, Pricing, and Allocations. J. Financ. 2002, 57, 1795–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J.K. Market Structure and Stabilization Policy. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1957, 39, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, B.; Rutherford, M.; Oswald, S.; Gardiner, L. An Empirical Investigation of the Growth Cycle Theory of Small Firm Financing. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2005, 43, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, J. Revenues, Expenses, Profitability and Investments of Potential Contenders for the Status of a Listed Company in Poland. Oeconomia Copernicana 2016, 6, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J.K. Strategy and Organizational Planning. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1983, 22, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, J.; Łuczka, T. The Structure of Venture Capital Raising by Companies in Poland and Central and Eastern Europe: Selected Aspects. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference IMECS, Prague, Czech Republic, 26–27 May 2016; Ivana Svobodová. Oeconomica Publishing House: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016; pp. 418–431. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, R.; Szafarz, A. Testing the information structure of Eastern European markets: The Warsaw Stock Exchange. Econ. Plan. 1997, 30, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosionek-Schweda, M. The Use of Discriminant Analysis to Predict the Bankruptcy of Companies Listed on the NewConnect Market. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2014, 9, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, E.S.; Marcum, T.M. Heed Our Advice: Exploring How Professionals Guide Small Business Owners in Start-Up Entity Choice. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metrick, A.; Yasuda, A. Venture Capital and Other Private Equity: A Survey. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2011, 17, 619–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanacker, T.; Manigart, S. Venture Capital. In Alternative Investments: Instruments, Performance, Benchmarks, and Strategies; Baker, H.K., Filbeck, G., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).