Abstract

In a situation where only one in three companies in the world is founded and run by women, there is a need to look for determinants, as well as for ways of solving specific problems. The aim of the article is to define the characteristics of female entrepreneurship and its role in creating and developing enterprises, in juxtaposition with male entrepreneurship. The article presents the results of the authors’ own research on selected problems of female entrepreneurship in Poland. They are based on surveys conducted among 200 people: female and male university students and identify the main problems of female entrepreneurship.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship significantly contributes to the creation of the macroeconomic values (see: [1] (pp. 259–275). While research on entrepreneurship has quite a long tradition, research into female entrepreneurship is a relatively recent phenomenon [2] (pp. 217–226). Therefore the question posed by E. Loza continues to resound today: Why do we never hear of a self-made woman [3] (pp. 26–64). H. Ahl has pointed to the need to revise the approaches to female entrepreneurship [4] (pp. 595–621).

The literature points out the “country effect” [5] (pp. 325–341); [6] (pp. 70–97) and the “gender effect”: women’s businesses are smaller, focus more on the services sector, and grow slower [7] (pp. 1–10); [8,9]. The research of female entrepreneurship will identify the barriers of women’s businesses [10] (pp.151–174); [11] (pp. 367–383) and is abundant in a variety of factors, such as the ethnic aspect [12] (pp. 192–208), or the problem of discrimination of women as regards access to bank credit [13] (also: [14] (pp. 2968–2984); [15] (pp. 930–943).

2. Research Procedure and Methods

The research was conducted among 200 women and men at the end of 2016 to determine their entrepreneurial attitudes and the main barriers to the development of their businesses.

3. Research Objectives

The aim of the study was to define the features of female entrepreneurship and its role in the establishment and development of enterprises, as compared to male entrepreneurship.

4. Methodology and Data

The presented results of empirical research were derived from surveys conducted among 200 people: female (61%) and male (37%) university students (2%: no answer). The research focused on perception of barriers of entrepreneurship. The main trends observed in Poland, with particular emphasis on the entrepreneurial attitudes of women, were presented through figures and tables.

5. Key Findings

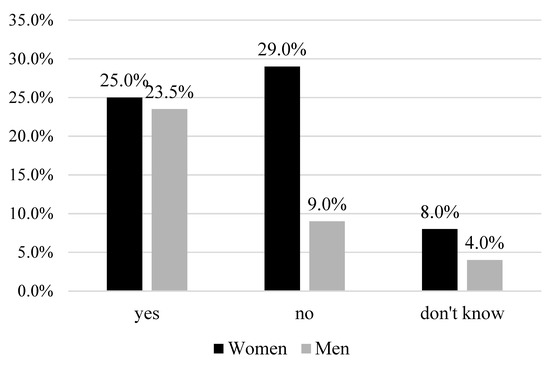

National economies have seen in recent decades a growing trend in women’s entrepreneurship (see also: [16] (pp. 204–214). Similar tendencies are observed in Poland: 29% of women do not consider starting a business and this attitude differs significantly in comparison with men. Similarly, twice as many women remain undecided about their plans in this regard (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Women’s and men’s readiness to set up a business in the future. Source: Own research.

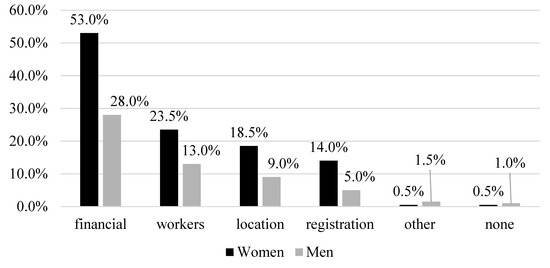

The reasons for women’s entrepreneurship should be seen in the perception of barriers. According to the data women perceive them twice as intensely as men (Figure 2). The phenomenon of female entrepreneurship remains in a crucial relationship to the approach to resolving the conflict between entrepreneurial activity, on the one hand, and motherhood, on the other hand. It seems that in Poland this conflict is not significant: according to the results of the as many as 64.5% of women still want to continue to work for themselves, or slightly reduce its intensity (36.3%). Only 0.8% of women anticipate shutting down the business for his reason, and 24.2% want to take maternity leave (Table 1). For comparison, in Germany, having children slightly limits female entrepreneurship [17], [18] (pp. 36–50); [19] (pp. 350–368).

Figure 2.

Barriers to setting up their own business according to women and men [%]. Source: Own research.

Table 1.

Entrepreneurial activity and motherhood in the opinion of women.

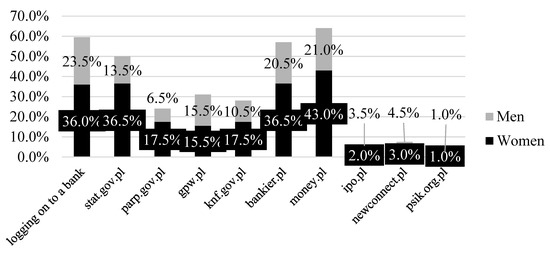

The decision to set up and run an enterprise requires the adequate knowledge. Due to the fact that the surveyed women and men indicated the financial barrier, the authors decided to check whether, and to what extent, they are familiar with the major websites containing relevant information on access to the money and capital markets. Generally, women sought information about the possibilities of financing their enterprises two, or even three, times more often than men (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structure of financial market websites used by women and men. Source: Own research.

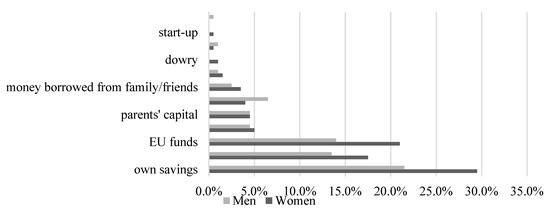

As regards the sources of financing of newly established enterprises, the main contribution in the case of both women and men were their own savings, with 29.5% of women availing of this resource (which is 8 pp more than men), EU funds (21% of women and 14% of men). (Figure 4). Venture capital and start-up financing play an even smaller role in the creation of enterprises, (see also: [20] (pp. 91–122. The literature on the subject points out that the supply of bank loans for women running a business discriminates them on the grounds of sex, price and ethnic [12]—women are extended loans on worse conditions: they are given higher interest rates and are asked to present higher guarantees [10] (pp. 151–174), [13,15]; [14] (pp. 2968–2984). Women also have hampered access—for various reasons—to other sources of funding [21] (pp. 503–521).

Figure 4.

Structure of the sources of financing of enterprises set up by women and men [%]. Source: Own research.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The evolution of the position of women, both in the family and in society, naturally creates the need for research into how female entrepreneurship is initiated and developed. This need is all the more justified as every year a significant number of women across many countries obtain university diplomas in various fields and feel increasingly stronger about self-fulfilment. The results of the authors’ research identify the main problems of female entrepreneurship, the degree of their readiness (compared to men) to set up their own business, the awareness of the factors that influence this process, including the conflict between business and motherhood, and the methods of solving it. Research on female entrepreneurship points to many further issues to be resolved.

References

- Łuczka, T. New Challenges for SMEs in 21th Century. In Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development in the 21th Century; Piasecki, B., Ed.; Łódź University Press: Łódź, Poland, 2002; pp. 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S.A.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza, E. Female Entrepreneurship Theory: A Multidisciplinary Review of Resources. J. Women’s Entrep. Educ. 2011, 1–2, 26–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ahl, H. Why Research on Women Entrepreneurs Needs New Directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheul, I.; Thurik, R.; Grilo, I.; van der Zwan, P. Explaining preferences and actual involvement in self-employment: Gender and the entrepreneurial personality. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P.A. Women’s participation in self-employment in Western industrialized nations. Int. J. Sociol. 2001, 31, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rietz, A.; Henrekson, M. Testing the Female Underperformance Hypothesis. Small Bus. Econ. 2000, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath Cohoon, J.; Wadhowa, V.; Mitchell, L. Are Successful Women Entrepreneurs Different from Men? The Anatomy of an Entrepreneur; Kauffman Foundation of Entrepreneurship: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2010; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.686.9519&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 13 February 2018).

- Robb, A.; Coleman, S.; Stangler, D. Source of Economic Hope: Women’s Entrepreneurship; Kauffman Foundation: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.kauffman.org/~/media/kauffman_org/research%20reports%20and%20covers/2014/11/sources_of_economic_hope_womens_entrepreneurship.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2018).

- Coleman, S. Constraints Faced by Women Small Business Owner: Evidence from the Data. J. Dev. Entrep. 2002, 7, 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes, J.P.; Miller, D.C.; Schafer, W.D. Gender Differences in Risk Taking: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 3, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperopoulos, P. Ethnic female business owners: More female or more ethnic entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.; Vos, E. SME Capital Structure: The Dominance of Demand Factors. In Proceedings of the 22nd Australasian Finance and Banking Conference, Sydney, Australia, 16–18 December 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluci, A.; Borisov, A.V.; Zazzaro, A. Does Gender Matter in Bank-Firm Relationship? Evidence from Small Business Lending. J. Bank. Financ. 2009, 34, 2968–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.; Levin, P.; Zimmerman, D. Discrimination in the small-business credit market. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2008, 85, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M.; Naderi Mahdei, N. Understanding role Models and Gender Influences on Entrepreneurial Intentions Among College Students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht, R.; Lauxen-Ulbrich, M. Selbstandige Frauen in Deutschland: Entwicklung, Wirtschaftliche Orientung und Ressourcen. 2005. Available online: www.ifm.uni-mannheim.de/unter/fsb/nr3.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2018).

- Lohman, H.; Luber, S. Trends in Self-Employment in Germany: Different Types, Different Developments. In The Reemergence of Self-Employment. A Comparative Study of Self-Employment Dynamics and Social Inequality; Arum, R., Muller, W., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- DeMartino, R.; Barbato, R.; Jacques, P.H. Exploring the Career/Achievement and Personal Life Orientation Differences between Entrepreneurs and Non-Entrepreneurs: The Impact of Sex and Dependents. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, J. Revenues, Expenses, Profitability and Investments of Potential Contenders for the Status of a Listed Company in Poland. Oeconomia Copern. 2016, 6, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Blease, J.R.; Sohl, J.E. Do women-owned business have equal access to angel capital. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).