A Study on the Perceptions of Autistic Adolescents towards Mainstream Emotion Recognition Technologies †

Abstract

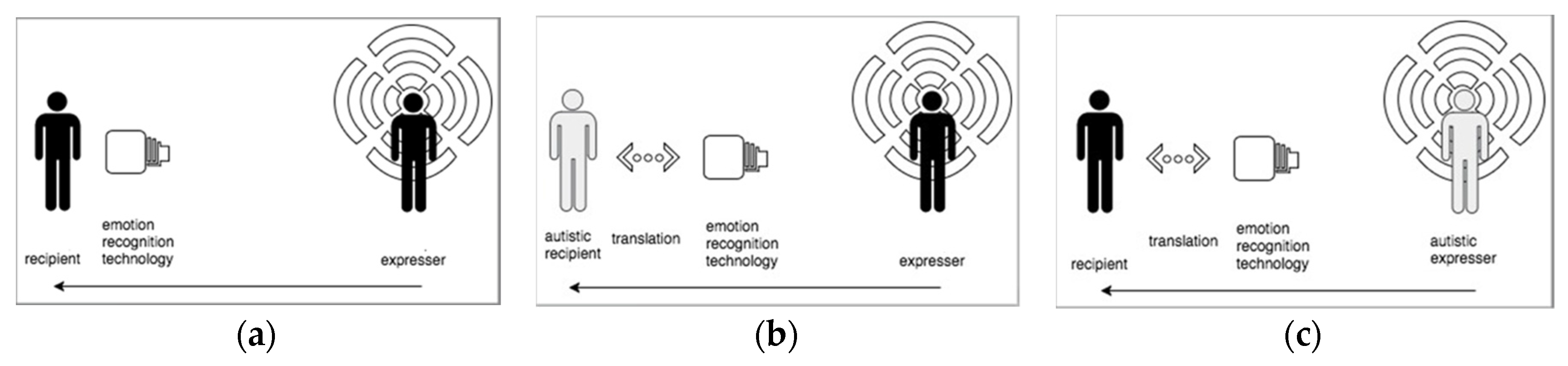

:1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Study Objective

4. Methods

4.1. Choice of Emotion Recognition Technologies

4.2. Online Survey

4.3. Interviews

4.4. Ethical Considerations

5. Results

5.1. Online Survey

5.2. Interviews

5.2.1. Wearable on the Wrist

5.2.2. Health Patch

5.2.3. Infrared Camera

5.2.4. Preferred Product

5.2.5. Privacy

6. Discussion

- Use physiological signals, because these signals are trustworthy to monitor emotions in autistic people. Other signals such as facial expressions, body language and voice intonation are employed differently by autistic people and are therefore not reliable to translate the emotions of an autistic adolescent to others.

- A multifunctional smartwatch design around the wrist would be best to monitor emotions based on physiological signals. A health patch would be the second choice. Autistic adolescents generally dislike the usage of (infrared) cameras.

- There should be a clearly recognizable on/off button to start or halt the monitoring of emotions in order to give the expresser control over the device.

- The design should be familiar to a product known by the expresser; e.g., a normal watch or a skin-coloured band-aid.

- The design should not be dangling, not too tight, and as flexible as possible; a smartwatch band should have different length possibilities and a health patch should be flexible enough not to pull the skin during regular or abrupt movements.

- Textures are important because of the sensitivity of the skin of autistic people [2]. For the smartwatch, a natural band of smooth texture is advisable. Leather could be possible. Metal or ceramics might be an option because of the smoothness and the thermal properties of this material that keep it at skin temperature.

- For all used materials, possible allergies of the expresser should be taken into account.

- Putting a product on, and taking it off, should be as simple and painless as possible for the expresser.

- Surfaces have to be flat, so no raised bumps or protruding buttons.

- An indication that shows monitoring is on/off is preferred, but not in the form of (blinking) lights that draw attention and distracts the expresser.

- Avoid a medical-looking design by hiding electrodes from view and not making the design predominantly white.

- Make inputs and outputs available to both the expresser as the recipient, for example through a smartphone app.

- A recipient should be accepted or certified by the expresser to allow viewing the emotions of the latter.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Data and Statistics | Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | NCBDDD | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Milton, D. So what exactly is autism? AET Competence framework for the Department for Education. 2012. Available online: http://www. aettraininghubs. org. uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/1_So-what-exactly-is-autism. Pdf (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Sinclair, J. Why I dislike “person first” language. Autonomy, the Critical Journal of Interdisciplinary Autism Studies. 2013. Available online: http://www.larry-arnold.net/Autonomy/index.php/autonomy/ article/view/OP1/html_1 (accessed on 17 October 2018).

- Samson, A.C.; Huber, O.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation in Asperger’s syndrome and high-functioning autism. Emotion 2012, 12, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearss, K.; Johnson, C.; Smith, T.; Lecavalier, L.; Swiezy, N.; Aman, M.; McAdam, D.B.; Butter, E.; Stillitano, C.; Minshawi, N.; et al. Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015, 313, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsmond, G.I.; Krauss, M.W.; Seltzer, M.M. Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grynszpan, O.; Weiss, P.L.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Gal, E. Innovative technology-based interventions for autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Autism 2014, 18, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berggren, S.; Fletcher-Watson, S.; Milenkovic, N.; Marschik, P.B.; Bölte, S.; Jonsson, U. Emotion recognition training in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of challenges related to generalizability. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2018, 21, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharmin, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Saha, A.; Das, M.; Maxwell, M.; Ahmed, S. From Research to Practice: Informing the Design of Autism Support Smart Technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Jerritta, S.; Murugappan, M.; Nagarajan, R.; Wan, K. Physiological signals based human emotion recognition: A review. In Signal Processing and its Applications (CSPA). In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th International Colloquium, Penang, Malaysia, 4–6 March 2011; pp. 410–415. [Google Scholar]

- Sherer, M.R.; Schreibman, L. Individual behavioral profiles and predictors of treatment effectiveness for children with autism. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yirmiya, N.; Kasari, C.; Sigman, M.; Mundy, P. Facial expressions of affect in autistic, mentally retarded and normal children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1989, 30, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czapinski, P.; Bryson, S.E. Reduced facial muscle movements in Autism: Evidence for dysfunction in the neuromuscular pathway? Brain Cogn. 2003, 51, 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Loveland, K.A.; Tunali-Kotoski, B.; Pearson, D.A.; Brelsford, K.A.; Ortegon, J.; Chen, R. Imitation and expression of facial affect in autism. Dev. Psychopathol. 1994, 6, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, K.A.; Hass, C.J.; Naik, S.K.; Lodha, N.; Cauraugh, J.H. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: A synthesis and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 1227–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, K.A.; Kimberg, C.I.; Radonovich, K.J.; Tillman, M.D.; Chow, J.W.; Lewis, M.H.; Hass, C.J. Decreased static and dynamic postural control in children with autism spectrum disorders. Gait Posture 2010, 32, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, K.A.; Amano, S.; Radonovich, K.J.; Bleser, T.M.; Hass, C.J. Decreased dynamical complexity during quiet stance in children with autism spectrum disorders. Gait Posture 2014, 39, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwood, A.; Frith, U.; Hermelin, B. The understanding and use of interpersonal gestures by autistic and Down’s syndrome children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1988, 18, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, H.; Rutter, M.; Howlin, P.; Rios, P.; Conteur, A.L.; Evered, C.; Folstein, S. Recognition and expression of emotional cues by autistic and normal adults. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1989, 30, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadig, A.; Shaw, H. Acoustic and perceptual measurement of expressive prosody in high-functioning autism: Increased pitch range and what it means to listeners. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edition, F. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, R.W. Future affective technology for autism and emotion communication. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3575–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.; Davis, R.; Hill, E. The effects of autism and alexithymia on physiological and verbal responsiveness to music. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bölte, S.; Feineis-Matthews, S.; Poustka, F. Brief report: Emotional processing in high-functioning autism—physiological reactivity and affective report. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, C.; Lombardo, M.V.; Auyeung, B. Alexithymia in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, G.; Yonezawa, T.; Kurita, K.; Tsumura, N. Monitoring Emotion by Remote Measurement of Physiological Signals Using an RGB Camera. ITE Trans. Media Technol. Appl. 2018, 6, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HealthPatch® MD-MediBioSense. Available online: http://www.medibiosense.com/products/healthpatch/ (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- NVA-Actuele Oproepen. Available online: http://www.autisme.nl/prikbord/deelnemers-aan-onderzoek-gezocht/actuele-oproepen.aspx (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Gear S3 Frontier 46 mm Smartwatch (Bluetooth) Dark Gray. Available online: https://www.samsung.com/us/mobile/wearables/smartwatches/samsung-gear-s3-frontier-sm-r760ndaaxar/ (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Angel Sensor M1—AngelList. Available online: https://angel.co/projects/170164-angel-sensor-m1?src=startup_profile (accessed on 31 May 2018).

- Microsoft Xbox 360 Kinect Review: Microsoft Xbox 360 Kinect—CNET. Available online: https://www.cnet.com/uk/products/microsoft-xbox-360-kinect/review/ (accessed on 31 May 2018).

| Respondents (n = 72) | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) Parents about their child (age 10–18) | (2) Autistic adult | |

| Number of responses | 18 (25%) | 54 (75%) |

| Gender | Male 14 (78%) Female 4 (22%) | 17 (32%) 37 (69%) |

| Age | 10 years 3 (17%) 11 years 3 (17%) 12 years 2 (11%) 13 years 3 (17%) 14 years 1 (6%) 15 years 0 (0%) 16 years 1 (6%) 17 years 5 (28%) | 18–24 years 13 (24%) 25–29 years 5 (9%) 30–34 years 3 (6%) 35–39 years 8 (15%) 40–44 years 6 (11%) 45–49 years 9 (17%) 50–54 years 5 (9%) 55–59 years 2 (4%) ≥60 years 3 (6%) |

| Questions on Expressing Emotions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1. Do you ever have trouble expressing your emotions? | Never Almost never Sometimes Often Very often Don’t know | 0 (0%) 1 (6%) 3 (17%) 10 (56%) 4 (22%) 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) 3 (6%) 16 (30%) 15 (28%) 19 (35%) 1 (2%) |

| Q2. Do you ever have the feeling that others do not understand what you feel? | Never Almost never Sometimes Often Very often Don’t know | 0 (0%) 1 (6%) 0 (0%) 9 (50%) 7 (39%) 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) 1 (2%) 12 (22%) 16 (30%) 24 (44%) 1 (6%) |

| Q3. Are you ever confused about what you are feeling? | Never Almost never Sometimes Often Very often Don’t know | 0 (0%) 1 (6%) 5 (28%) 5 (28%) 6 (33%) 1 (6%) | 1 (2%) 7 (13%) 21 (39%) 12 (22%) 12 (22%) 1 (2%) |

| Q4. Are there situations where you would like others to know what you are feeling? | Never Almost never Sometimes Often Very often Don’t know | 0 (0%) 1 (6%) 5 (28%) 7 (39%) 4 (22%) 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) 2 (4%) 19 (35%) 16 (30%) 16 (30%) 1 (2%) |

| Q5. Would you like it if others would know what you are feeling? | Never Almost never Sometimes Often Very often Don’t know | 0 (0%) 0 (6%) 3 (17%) 10 (56%) 4 (22%) 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) 2 (4%) 15 (28%) 20 (37%) 15 (28%) 2 (4%) |

| Questions on (Wearable) Technologies | |||

| Q6. Do you use an emotion communication technique? | Yes No Don’t know | 1 (6%) 17 (94%) 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) 52 (96%) 0 (0%) |

| Q7. Have you ever worn a physiological sensor (biosensor)? | Yes No Don’t know | 1 (6%) 17 (94%) 0 (0%) | 8 (15%) 46 (85%) 0 (0%) |

| Q8. Is wearing a watch bothersome? | Yes No Don’t know | 8 (44%) 10 (56%) 0 (0%) | 16 (30%) 38 (70%) 0 (0%) |

| Q9. Is wearing a patch bothersome for you? | Yes No Don’t know | 5 (28%) 10 (56%) 3 (17%) | 15 (28%) 35 (65%) 3 (6%) |

| Q10. Would wearing a patch be less bothersome when there is a nice picture on the patch? | Yes No Don’t know | 1 (6%) 14 (78%) 3 (17%) | 5 (9%) 45 (83%) 4 (7%) |

| Q11. Is being photographed bothersome for you? | Yes No Don’t know | 10 (56%) 7 (39%) 1 (6%) | 27 (50%) 22 (41%) 5 (9%) |

| Q12. Is being filmed bothersome for you? | Yes No Don’t know | 12 (67%) 5 (28%) 1 (6%) | 37 (69%) 12 (22%) 5 (9%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nijeweme-d’Hollosy, W.O.; Notenboom, T.; Banos, O. A Study on the Perceptions of Autistic Adolescents towards Mainstream Emotion Recognition Technologies. Proceedings 2018, 2, 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191200

Nijeweme-d’Hollosy WO, Notenboom T, Banos O. A Study on the Perceptions of Autistic Adolescents towards Mainstream Emotion Recognition Technologies. Proceedings. 2018; 2(19):1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191200

Chicago/Turabian StyleNijeweme-d’Hollosy, Wendy Oude, Tamara Notenboom, and Oresti Banos. 2018. "A Study on the Perceptions of Autistic Adolescents towards Mainstream Emotion Recognition Technologies" Proceedings 2, no. 19: 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191200

APA StyleNijeweme-d’Hollosy, W. O., Notenboom, T., & Banos, O. (2018). A Study on the Perceptions of Autistic Adolescents towards Mainstream Emotion Recognition Technologies. Proceedings, 2(19), 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2191200