Body as Anti-Anthropomorphic Landscape: Traumatic Structure in Bog Body †

Abstract

1. Introduction: Body as Anti-Anthropomorphic Landspace

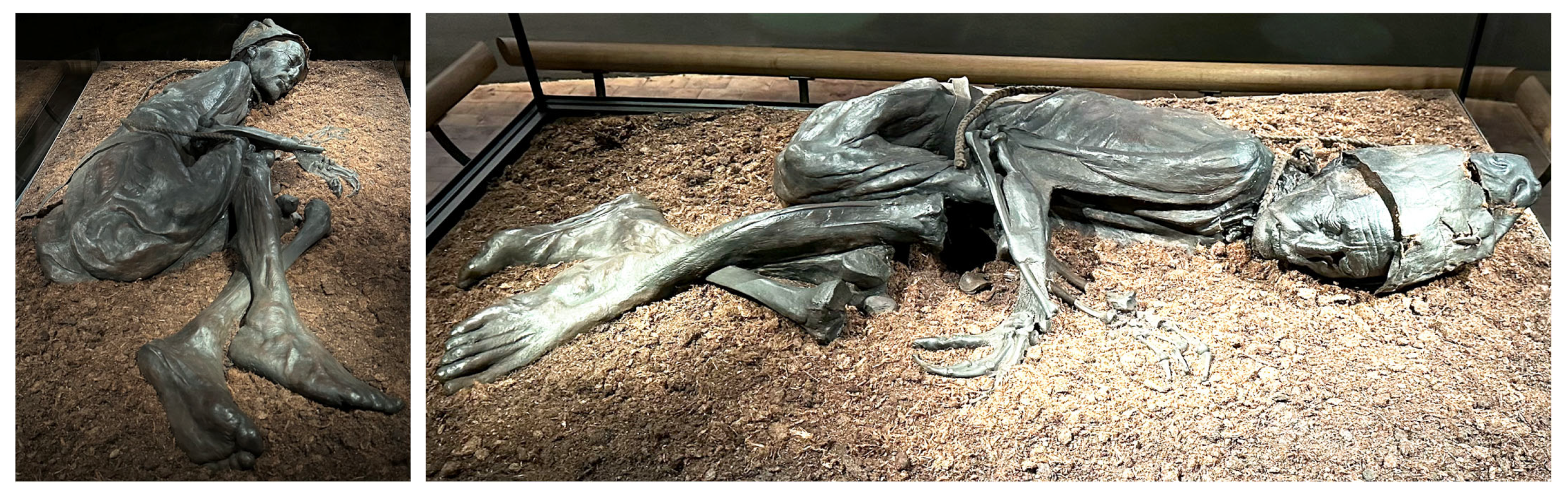

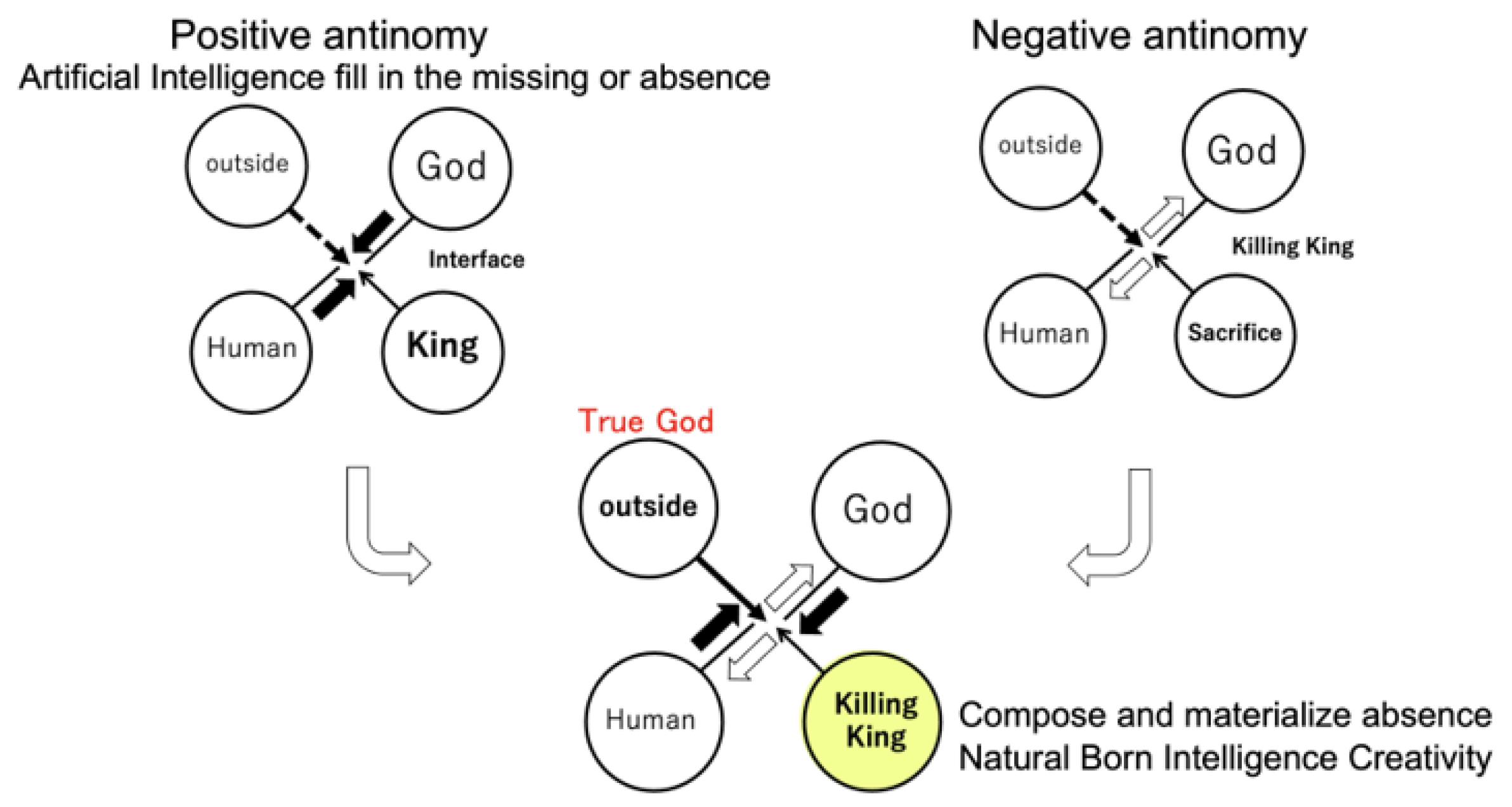

2. King Killed and Installed as Bog Body

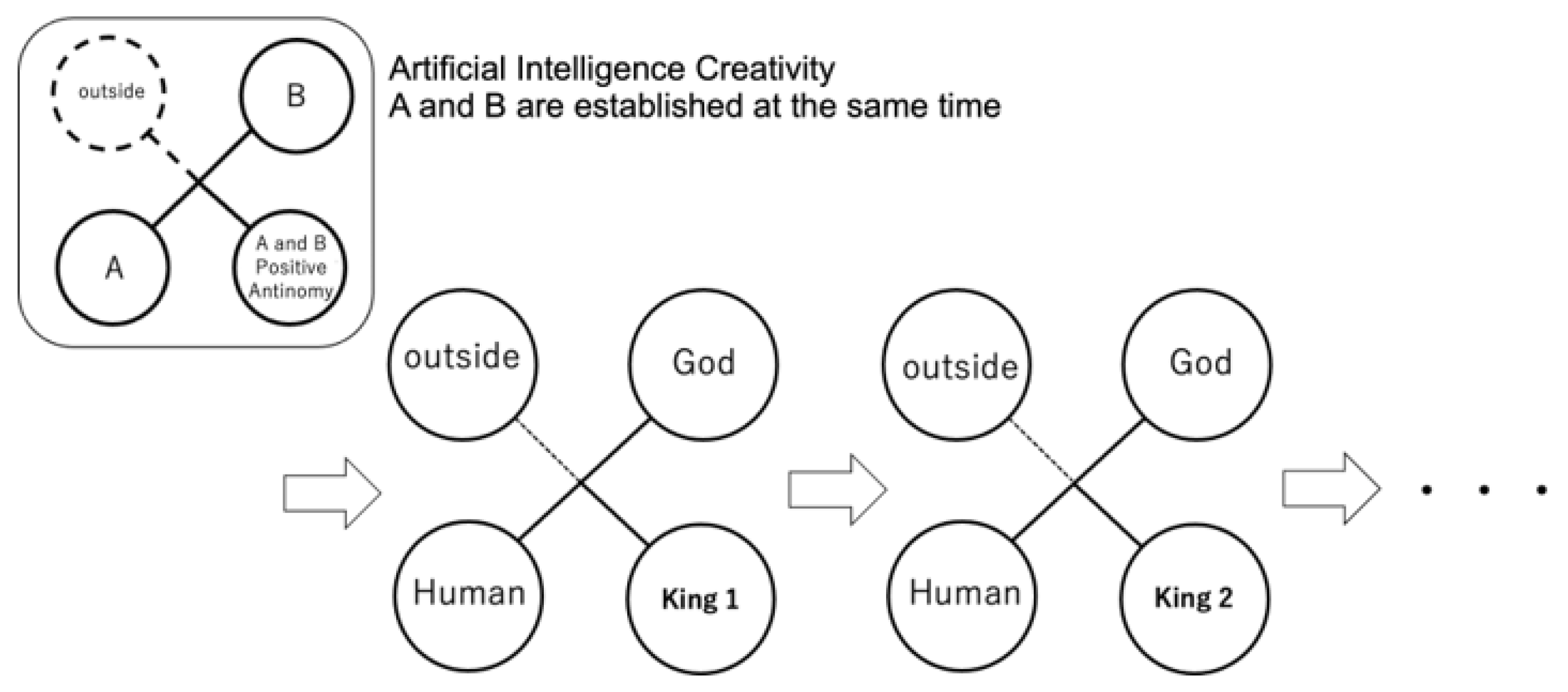

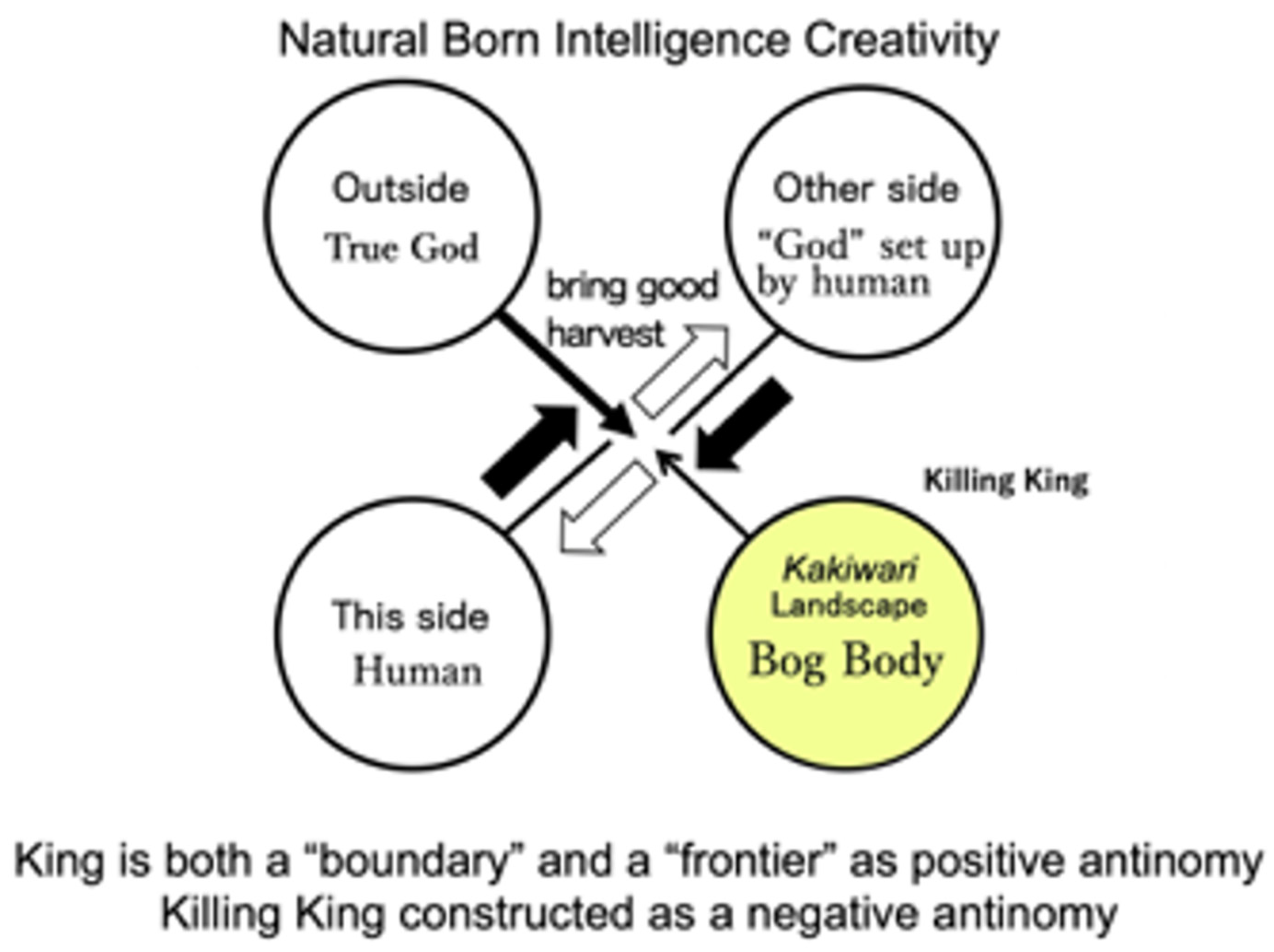

3. Creativity of Traumatic Structure from Natural Born Intelligence

4. Materialization of Absence in Japanese Painting: The Kakiwari Structure and Natural Born Intelligence

5. Artistic Practice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Collections of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium Cover a Period Extending from the 15th to the 21st Centuries. Available online: https://fine-arts-museum.be/fr/la-collection/?string=Paysage+anthropomorphe (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Baltrušaitis, J. Aberations; Tanemura, S.; Iwaya, K., Translators; KOKUSHOKANKOKAI Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McTiernan, J. Predator; 20th Century Fox: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fourier, C. The Theory of the Four Movements; Iwaya, K., Translator; Shichosha: Tokyo, Japan, 1970; Volume 1/Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, G. Bartleby, o, Della Contingenza; Takakuwa, K., Translator; GETSUYOSHA Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Melville, H. Bartleby, the Scrivener; Parker, H., Ed.; Takakuwa, K., Translator; GETSUYOSHA Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, K. Fourier no Mirai no Nikutai to shite no Han-Kofun—Iya Haka Toha? (The Anti-Tumulus as Fourier’s Future Body—Or, What Is a Grave?). In Charles Fourier no Shin Sekai (Charles Fourier’s New World); Fukushima, T., Ed.; Suiseisha: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp. 391–420. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C. Tollund Man: Gift to the Gods; The History Press Ltd.: Great Britain, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, T.; Downey, L.; Synnott, C.; Kelly, E.P.; Stanton, C. Composition of ancient Irish bog butter. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, R.; Quik, C.; Bergerbrant, S.; Hulsman, F.; Kama, P. Bogs, bones and bodies: The deposition of human remains in northern European mires (9000 BC–AD 1900). Antiquity 2023, 97, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.P. Secrets of the Bog Bodies: The Enigma of the Iron Age Explained. Archaeol. Irel. 2006, 20, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Treadway, T.; Twumasi, C. An Experimental Study of Lesions Observed in Bog Body Funerary Performances. EXARC J. 2021. Available online: https://exarc.net/ark:/88735/10595 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Gunji, Y.P. Ten-Nen Chinou (Natural-Born Intelligence); Kodansha Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Gunji, Y.P.; Nakamura, K. Psychological Origin of Quantum Logic: An Orthomodular Lattice Derived from Natural-Born Intelligence without Hilbert Space. BioSystems 2022, 215, 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Gunji, Y.P. Painted Board Girls as the Device towards De-creation. Cocreationology 2020, 2, 1–12. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art. Available online: http://spmoa.shizuoka.shizuoka.jp/japanese/collection/symphony/fukei/pt1_30.php (accessed on 20 October 2025). (In Japanese).

- Nakamura, K.; Gunji, Y.P. Tankuri: Shooting Creativity; Suiseisha: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Gunji, Y.P. Yatte-Kuru (Something Coming); IGAKU-SHOIN Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, K. De-Creation in Japanese Painting: Materialization of Thoroughly Passive Attitude. Philosophies 2021, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunji, Y.P.; Nakamura, K. Kakiwari: The device summoning creativity in art and cognition. In Unconventional Computing, Philosopies and Art; Adamatzky, A., Ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022; pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K. Affectus, or Carving Emptiness into the Body. In Affectus; Nishii, R., Yanai, T., Eds.; Kyoko University Press: Kyoto, Japan, Trans Pacific Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp.1–26.

- Kokeshi Wiki. (In Japanese). Available online: https://kokeshiwiki.com/?p=3959 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Kokeshi Wiki. (In Japanese). Available online: https://kokeshiwiki.com/?p=6697 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- The exhibition “Place of Landscape” by Kyoko Nakamura and Yukio Pegio Gunji, Exhibition at Art Space Kimura (ASK), Tokyo. 2025. Available online: https://youtu.be/mt7ztSe9vGQ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- The exhibition “BOG BODY—The Summoned Body” by Kyoko Nakamura and Yukio Pegio Gunji, Exhibition at Art Space Kimura (ASK), Tokyo. 2024. Available online: https://youtu.be/l27Fd4Yg9EE (accessed on 10 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakamura, K.; Gunji, Y.P. Body as Anti-Anthropomorphic Landscape: Traumatic Structure in Bog Body. Proceedings 2025, 126, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025126019

Nakamura K, Gunji YP. Body as Anti-Anthropomorphic Landscape: Traumatic Structure in Bog Body. Proceedings. 2025; 126(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025126019

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakamura, Kyoko, and Yukio Pegio Gunji. 2025. "Body as Anti-Anthropomorphic Landscape: Traumatic Structure in Bog Body" Proceedings 126, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025126019

APA StyleNakamura, K., & Gunji, Y. P. (2025). Body as Anti-Anthropomorphic Landscape: Traumatic Structure in Bog Body. Proceedings, 126(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025126019