Abstract

Forest fires cause significant harm to ecological communities and society by altering land cover changes, imposing economic burdens, and exacerbating global warming and climate change. Based on burned areas and their land cover, this study analyzes the burned areas in Portugal’s Guarda District. It examines the environmental and economic impacts of the forest fires occurring in August 2022. The results highlight that 9.42% of the Pinus Sylvestris, a native species of the Serra da Estrela Natural Park, was lost, alongside other ecological damage, including a decrease in greenhouse gas (GHG) sequestration capacity and soil degradation, which increases the risk of erosion and reduces the fertility of the affected areas. The economic impact was also substantial, with significant costs related to firefighting efforts, loss of timber resources, and adverse effects on tourism and local livelihoods.

1. Introduction

Forests and soil are resilient and crucial carbon reservoirs. They absorb significant carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, contributing to the global carbon cycle. Forests, with their microclimate regulation, influence temperature and humidity, and are essential for mitigating climate change’s harmful effects [1]. In the summer, temperature differences can increase by up to 10 °C between forests and adjacent urban areas [1,2]. The impact of such forest fires is not limited to the environment, but also extends to substantial economic and social repercussions. Despite the challenges, forests continue to thrive, occupying 43.5% of Europe’s land area, increasing by almost 10% between 1990 and 2020 [3]. In Portugal, forests are the primary land use, covering 36% of the territory [4]. Forests, having the ability to act as carbon sources or carbon sinks, are a testament to their resilience. On the one hand, forest carbon is released when trees burn or decay after dying, but on the other hand, forest is also a carbon sink if it absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere through photosynthesis than it releases [5]. In the world’s forests, over a trillion tons of CO2 is stored in biomass [6], and EU forests absorb approximately 10% of the EU’s annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1,3], highlighting their role in mitigating climate change [7]. The amount of additional carbon that can be stored in forests depends on (1) how much society is willing to spend to store more carbon and (2) how quickly the carbon must be stored, i.e., the faster the carbon is stored, the more expensive it will be [6]. Carbon sinks play an essential role in the transition to climate neutrality in the EU [8], and, in particular, the agriculture, forestry, and land use sectors can make an essential contribution in that context. The Land Use, Land Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF) sector, acting as a carbon sink, is a central instrument to the EU’s overarching objective to reduce GHG emissions by 55% to 57% compared to 1990 levels and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 [8]. According to Regulation (EU) 2023/839 [8], each Member State in the LULUCF sector must set targets to increase GHG removals during the period 2026–2030, resulting in a target of 310 million of CO2 equivalent of net removals for the EU as a whole in 2030, which would further contribute to achieving the Union’s climate objectives. Forest fires also contribute to climate change, releasing substantial amounts of CO2 and other GHG, intensifying temperature rises and humidity decreases, and leading to more frequent and intense fires, compromising the carbon neutrality targets for 2050 [8]. The total burned area in Continental Portugal between 1st January and 31st August 2022, was 106,639 ha, 36% more than the annual average for 2012–2021 [9]. According to [9], 2022, up to August 31st, was the year with the sixth-highest number of fires and the fourth-highest value in burned area since 2012. The resultant decline in Portugal’s forest area from fires could jeopardize the EU’s 2030 goal to increase carbon sinks by 15%. Moreover, forest fires have far-reaching implications for territorial sustainability, causing significant changes in land cover and soil structure, water quality, geological hazards such as debris flows, landslides, and rockfalls, and post-fire hydrological events, among others [10], profoundly affecting ecological, economic, and social systems [11,12,13]. Supported by a literature review and using data on burned areas and their land cover, this study seeks to provide insights into the consequences of forest fires in the region. Thus, it presents a brief analysis of economic and environmental impacts resulting from forest fires in the Guarda District in August 2022.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

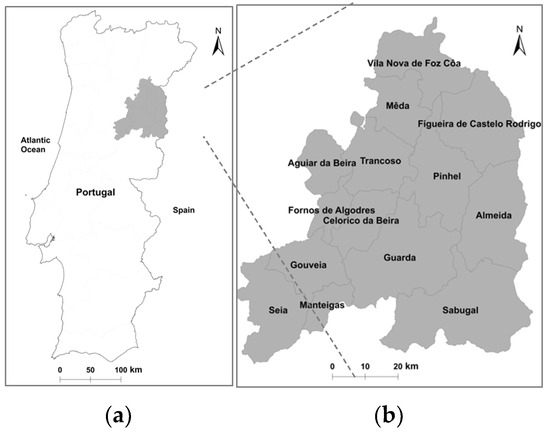

The emphasis of the analysis is placed on the Guarda District (Figure 1), whose territory suffered serious damage from the fires that occurred in August 2022. Guarda District is a territory with 5535.31 km2, with mountainous relief, including part of Serra da Estrela Natural Park, and has a population density of 25.83 inhabitants per km2.

Figure 1.

Study area. Geographical framework of the Guarda District (highlighted in gray) in Portugal (a); municipalities of Guarda District (b).

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. Land Cover

Land cover classes were analyzed, based on the Map of Land Use and Land Cover 2018 [14], to understand the changes in land cover and the impacts of forest fires in 2022. Accordingly, in 2018, the classes of wilds and forests prevailed with 334,192.13 ha, corresponding to 60.4% of the territory—176,654.330 ha (31.9%) by the forest class and 157,537.83 ha (28.5%) by the wild class. The resinous forest class occupied 15.1% (83,729.76 ha), distributed by 14% (77,362.66 ha) Pinus pinaster, 0.1% (476.49 ha) Pinus pinea, and 1% (5890.61 ha) other resinous (Pinus Sylvestris) classes. The hardwood forest (oaks, chestnut trees, holm oaks, cork oaks, invasive) class covered 92,924.54 ha (16.8%), and Eucalyptus only 0.6% (3383.41 ha) of the district area.

2.2.2. Burned Area/Land Cover

In August 2022, a large fire engulfed approximately 28,000 ha of the Serra da Estrela. Between 2nd and 22nd August 2022, 20,618 ha of the Guarda District area was scorched [12], causing significant changes in land cover. This area is a habitat for several protected autochthonous species, whose environment, once damaged by fires, often faces irreparable harm. Hence, the period from 2nd to 22nd August was selected for our analysis. Table 1 details the burned area by land cover type, focusing on forests and wilds classes.

Table 1.

Burned area in Guarda District by forest class and wild cover from 2nd to 22nd August 2022.

3. Results and Discussion

Considering Table 1, 78.31% of the burned area in August 2022 was forests and wilds: 7402.39 ha (35.90%) of forest and 8741.95 ha (42.40%) of wild. The hardwood forest, with 3213.62 ha, corresponds to 15.59% of the area affected by wildfires. Also, the Pinus pinaster had a significant burned area (2970.42 ha, i.e., 14.41%). The other resinous and eucalyptus classes burned 2.69% and 3.21%, respectively, and Pinus pinea was the class with the smallest burned area, 1.33 ha (0.006%). Considering the land cover area of each class in 2018, the following were burned: 3.84% of Pinus pinaster, 0.28% of Pinus pinea, 9.42% of other resinous, 3.46% of hardwood forest, 5.55% of wilds, and 19.57% of eucalyptus. The Pinus Sylvestris, classified as other resinous, is an autochthonous species from Serra da Estrela Natural Park, which is threatened and at risk of extinction, highlighting its small area (1% in 2018) of occupation in the district. The Pinus pinea, grown for its seed (pine nuts), also represents an environmental and economic loss, even the tiny burned area. Wood is used for several requests, with 3.84% of its burned area having negative economic impacts. Likewise, the 19.57% eucalyptus burned area presents economic losses. In addition, forest fires have a significant environmental impact, not only for releasing amounts of GHG but also due to the nature that dies and the loss of forests that no longer contribute to carbon sequestration and sinking. It is estimated that a hectare of trees can contain around 50 tons of carbon, approximately 180 tons of CO2 in the atmosphere [16], and sequester 1 to 2 tons of CO2 annually [17]. Some forests can store up to 10 tons of carbon per hectare, while others store much more, but according to these authors [16], the estimate of 50 tons per hectare would be typical for a young forest. Thus, it is legitimately estimated that 7402.39 ha of burned forest stopped storing 370,119.50 tons of carbon and sequestering 7402.39 to 14,804.78 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere per year. The burned wild area also stopped contributing to carbon absorption.

4. Conclusions

The 16,144.34 ha forest and wild areas burned in the Guarda District in August 2022 caused 9.42% of the Pinus Sylvestris, an autochthonous species from Serra da Estrela Natural Park, to disappear, beyond other ecological damage, such as the contribution of forest species to the reduction in GHG emissions. It was estimated that the 7402.39 ha of burned forest could hurt the sequestering CO2 of around 10,000 tons. Furthermore, other impacts occur at an economic and social level. Forest regeneration takes time, and full recovery is difficult, especially for native species. The decline in the population of plant species, particularly autochthonous species, is worrying, damaging the balance of habitats and ecosystems and the environment in general. Thus, this study provides some warnings about the consequences of forest fires that can present challenges to the sustainability of the territory, aspiring to facilitate a balanced coexistence between society and nature in this ecosystem.

Author Contributions

All authors (E.S., F.D. and P.M.S.M.R.) contributed equally to the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data will be made available on request to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- EEA. European Forest Ecosystems: Key Allies in Sustainable Development. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/european-forest-ecosystems-key-allies (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Haesen, S.; Lembrechts, J.J.; Frenne, P.; Lenoir, J.; Aalto, J.; Ashcroft, M.B.; Kopecký, M.; Luoto, M.; Maclean, I.; Nijs, I.; et al. ForestTemp-Sub-canopy microclimate temperatures of European forests. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 28, 7157–7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament. Climate Change: Better Using EU Forests as Carbon Sinks. 2023. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20170711STO79506/climate-change-better-using-eu-forests-as-carbon-sinks (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- ICNF. Portugal Perfil Florestal. 2021. Available online: https://www.icnf.pt/api/file/doc/1f924a3c0e4f7372 (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Natural Resources Canada. Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/climate-change/climate-change-impacts-forests/forest-carbon/13085 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Mendelsohn, R.; Sedjo, R.; Sohngen, B. Forest Carbon Sequestration. In Fiscal Policy to Mitigate Climate Change: A Guide for Policymakers; Parry, I.W.H., Mooij, R., Keen, M., Eds.; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Chapter 5; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Blumröder, J.; May, F.; Härdtle, W.; Ibisch, P.L. Forestry contributed to warming of forest ecosystems in northern Germany during the extreme summers of 2018 and 2019. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2021, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Regulation (EU) 2023/839 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 April 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/839/oj (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- DGPFR. 5.º Relatório Provisório de Incêndios Rurais de 2022; 5.º RPIR/DGPFR/2022; Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e Florestas—Divisão de Gestão do Programa de Fogos Rurais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- USAID/USFS. Portugal Wildfires. Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) Review. Report USAID/USFS 2022. Available online: https://www.icnf.pt/florestas/gfr/gfrgestaoinformacao/grfrelatorios/recuperacaodeareasardidas (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Lourenço, L. Forest fires in continental Portugal Result of profound alterations in society and territorial consequences. Méditerranée 2018, 130, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.C.M.; Nunes, A.; Sousa, A.; Lourenço, L. Mapping the Causes of Forest Fires in Portugal by Clustering Analysis. Geosciences 2020, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Pinto, L.C.; Valente, M. Forest fire causes and prevention strategies in Portugal: Insights from stakeholder focus groups. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 169, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGT. Especificações Técnicas da Carta de Uso e Ocupação do Solo (COS) de Portugal Continental para 2018; Relatório Técnico; Direção-Geral do Território: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, L. Mapeamento de Incêndios e Caracterização Geral do Território a Partir de Deteção Remota. Bachelor’s Thesis, Polytechnic of Guarda, Guarda, Portugal, December 2022. Available online: https://bdigital.ipg.pt/dspace/handle/10314/9521 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Climate Portal. How Many New Trees Would We Need to Offset Our Carbon Emissions? MIT Climate Portal; Available online: https://climate.mit.edu/ask-mit/how-many-new-trees-would-we-need-offset-our-carbon-emissions (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Klaus, J. Forests Change the Climate. Max Planck Res. 2020, 4, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).