Socio-Territorial Fractures and Multi-Scalar Cohesion Policies †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Social System: Characterized by intersectional stratification, the analysis examines a dystopian scenario marked by escalating inequality, potentially leading to socio-political instability and insecurity. In this context, there would be a significant rise in territorial disparities, residential segregation, and socio-spatial distancing, severely limiting access to opportunities and aspirations for vulnerable groups. Public policies would be challenged to foster equity and socio-territorial cohesion across multiple scales.

- Economic System: Defined by global capitalism, the analysis presents a dystopian model of unconscious developmentalism that fails to justify its role in meeting human needs. This scenario forecasts increasing market tensions and ongoing challenges in housing accessibility, particularly in regions with concentrated job opportunities like agglomeration economies. Amidst growing inefficiencies in meeting basic needs, discontent, uncertainty, and perceptions of relative deprivation would persist. Public policies would face the imperative of demonstrating efficacy in improving overall quality of life.

- Ecological System: Characterized by a planetary biosphere with predominantly finite resources, the analysis highlights a dystopian scenario of ongoing ecological degradation due to inefficient utilization of limited resources and non-circular metabolic processes. Public policies would confront the urgent necessity of promoting a just ecological transition, emphasizing the transformation of unsustainable mobility and transportation models.

3. Results: Challenges and Contradictions

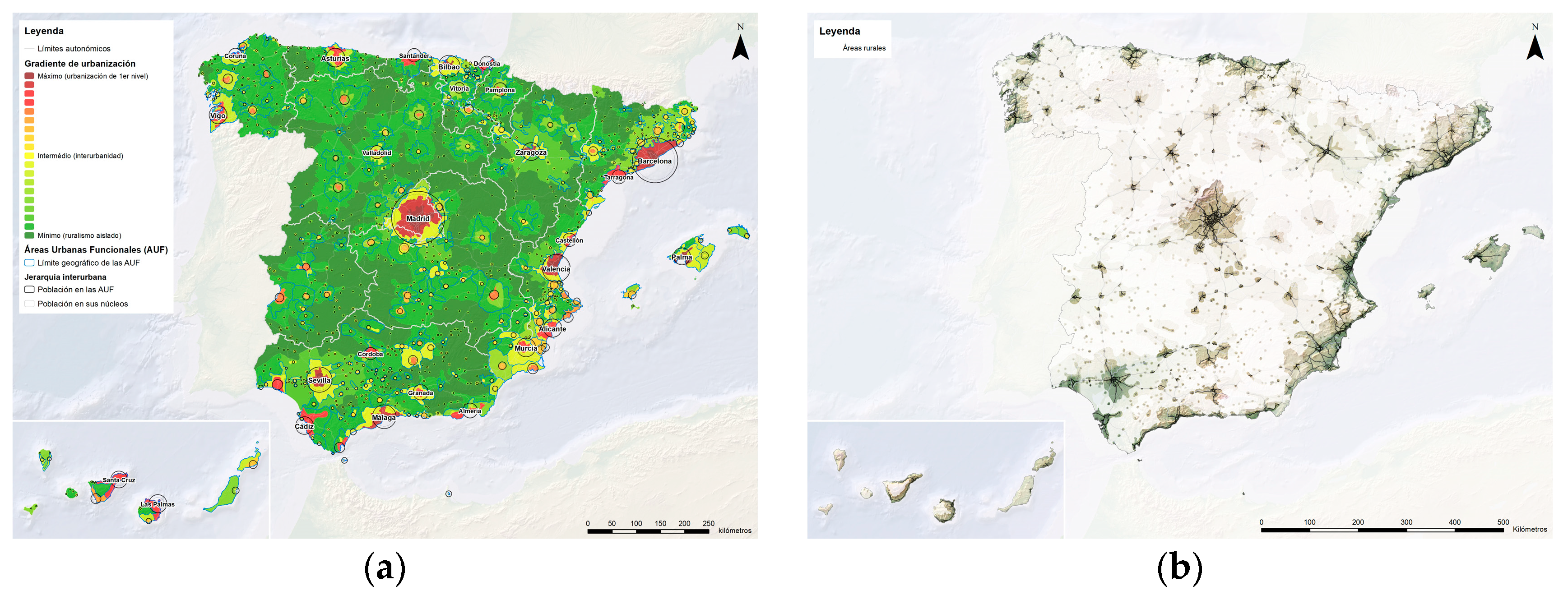

3.1. Socio-Territorial Scenarios and Their Consequences

3.2. Tension in Urban Markets: The Housing Problem

3.3. Transport and Mobility: Technology as an Unsustainable Incrementalist Escape

4. Discussion: Complex Context and Opportunity

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez Giménez, J.M. Desigualdades Socioterritoriales en España: La Reconfiguración del Sistema Interurbano Español; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://oa.upm.es/73966/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Gómez Giménez, J.M. Fracturas Socioespaciales en la Península Ibérica, 1986–2016. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 22 April 2022. Available online: https://drive.upm.es/s/Db5ct37Fs5Zg0zL (accessed on 23 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gómez Giménez, J.M.; Sá Marques, T.; Hernández Aja, A. Functional urban processes in Iberia: An approach to the integration of the urban territory beyond metropolization processes. Cuadernos Geográficos 2020, 59, 93–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Giménez, J.M. Urban inequality: Residential segregation in metropolitan contexts without integrated spatial planning. Cuad. Investig. Urbanística 2024, 154, 1–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.A.; Gil, J. Grassroots struggles challenging housing financialization in Spain. Hous. Stud. 2024, 39, 1516–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Institute. Population Projections. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/es/PROP20242074.htm (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Piketty, T. A Brief History of Equality; Belknap Press: Cambridge, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giménez, J.M.G. Socio-Territorial Fractures and Multi-Scalar Cohesion Policies. Proceedings 2025, 113, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025113014

Giménez JMG. Socio-Territorial Fractures and Multi-Scalar Cohesion Policies. Proceedings. 2025; 113(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025113014

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiménez, José Manuel Gómez. 2025. "Socio-Territorial Fractures and Multi-Scalar Cohesion Policies" Proceedings 113, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025113014

APA StyleGiménez, J. M. G. (2025). Socio-Territorial Fractures and Multi-Scalar Cohesion Policies. Proceedings, 113(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2025113014